Obtaining Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Obtaining Food at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 9

Obtaining Food at Sea in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries - Hunting

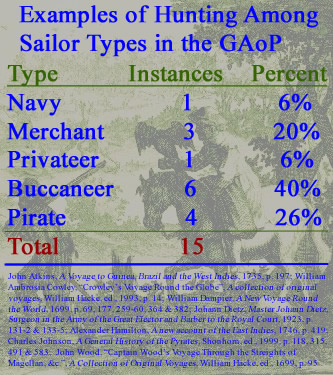

Exanples of Hunting By Sailor Types During the Golden Age of Piracy,

Image: Hunting in New England, From Naaukeurige versameling der

gedenk-waardigste (1707)

Another way for sailors to get food was to land on an undeveloped shore site and hunt for animals. There are only 15 examples of sailors hunting in the data under study. The breakdown of the number of instances for each sailor type can be seen in the chart at left. Buccaneers provide the most examples of hunting food, which makes sense given that buccaneers were specifically known as hunters. The second greatest number of instances is found among the pirates, which also makes sense given that they were less able to rely on normal channels of food procurement. Pirates generally tended to avoid populous places where they might be recognized because it could lead to their being arrested and hung.

What is somewhat curious is that there is only a single instance of a privateer hunting for food. As we have seen, nearly all the privateers were sailing to the New World, looking for ships and cities to seize in Central and South America during their voyages. Being Spanish-held, such places would have typically been unfriendly to them, so, like the pirates, the privateers would have often avoided large cities where they might be discovered and caught. (While the privateers had letters of marque from their government to protect them from being identified as pirates, the letters wouldn't be much good in trying to protect themselves from the Spanish who considered them pirates.)

Another way to look at this data is where the hunting took place. All but two of the privateer and buccaneer hunts were located in South or Central America. The remaining instances are from the East Indies. Examples of hunting by pirates occurred either in the West Indies or at their stronghold on Madagascar. The merchant accounts come from Java and Norway while the single naval hunting expedition took place in Africa. So there is quite a bit of diversity in locations.

Before looking at these accounts in detail, let's take a brief detour into the history of the hunting sailor from the period preceding that which is presented in this article.

Morgan's Buccaneers Hunting Food

It would hardly be fitting to discuss hunting as a food gathering technique amongst sailors without acknowledging the role of the buccaneers. The word 'buccaneers' is derived from the Arawack native word

Photo: Mission - A Recreated Boucan

for the platform made of sticks that was used to smoke meat: a buccan. The French modified the word to 'boucane' or 'boucan' and French hunters came to be called 'boucaniers.' The English further modified it into 'buccaneer', the word we know today.

From the English perspective, the arguable pinnacle of the buccaneers activity came under the direction of Henry Morgan, who attacked a variety of large Spanish settlements at Puerto Principe (modern Camagüey), Cuba, Portobello, Panama, Maracaibo, Venezuela and Panama City, among others. His attack methods were different from both the pirates and some of the late-era buccaneers which followed him. Most of Morgan's attacks took place under the official sanction of a letter of marque, so they have not been included in any of the other parts of this article. However, since hunting was so integral to the buccaneers in procuring food, some examples found in Alexandre Exquemelin's account of Morgan's buccaneers are included here. (Note that these have not been factored into the above data on hunting.)

To set the stage, Exquemelin explained how the buccaneers prepare a voyage and what their diet was once they embarked. First,

A Buccaneer and a Boucan, From Histoire des Avanturiers

Flibustiers, Vol1 (1744)

they joyn together in Council, concerning. what place they ought first to go unto, wherein to get provisions? Especially of flesh: seeing they scarce eat any thing else. And of this the most common sort among them is Pork. ....their allowance, twice a day, unto every one, is as much as he can eat; without either weight, or measure. Neither doth the Steward of the Vessel, give any greater proportion of flesh, or any thing else unto the Captain, then unto the meanest Mariner.1

If the diet was as free as he says, it would have been an ongoing to chore to keep the ship supplied with a sufficient quantity of meat. In preparation for a voyage undertaken in 1670, Morgan sent a "Party of his Men to hunt in the Woods, who killed there an large number of Beasts, and salted them"2. When they reached Boca del Drago on his way to Panama that year, Exquemelin explains that "some of our Men went into the Wood's to hunt, and others to catch other Fish."3 While they were careening their vessel some time later at the Bay of Bleevelt in Nicaragua, a group was again sent into the woods to recruit fresh meat. "Our Companions who went abroad to hunt, found hereabouts Porcupines, of a huge and monstrous bigness. But their chief Exercise was killing of Monkeys, and certain Birds, called by the Spaniards, Faisanes, or Pheasants."4 In fact, they hardly limited themselves to pork as Exquemelin had earlier suggested. At Isla de los Pinos, Cuba, "we killed ...and salted, an huge number of wild Cows, sufficient both to satiate our hungry Appetites, and to Victual our Vessel for the Sea. These Cows were formerly brought into this Island by the Spaniards, with design they should here multiply; and stock the Countrey with Cattel of this kind."5 The also took and salted several tortoises there.

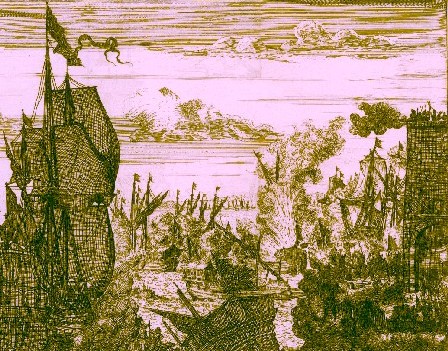

Buccaneer Attack on Spanish City, From Amerikaanse Zeerovers, Alexandre Exquemelin (1678)

The Spanish were so familiar with the buccaneers' desire for flesh, a fact that they used to set a trap for them in 1667 at Bahia Ocoa on Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic). They began by sending several hundred men there to hunt the wildlife to extinction, so "that if any Pirats [buccaneers] should return, they might find no subsistance."6 True to form, when the buccaneers came back, they went hunting, but having no luck went farther afield than normal on the hunt. "The Spaniards, who watched all their motions, gathered a great Herd of Cows, and set two or three men to keep them. The Pirats having spied this Herd, killed a sufficient number thereof... as soon as they attempted to carry them away, [the Spanish] set upon them with all fury imaginable, crying, Mata, mata; that is, Kill, kill."7 The buccaneers were then forced to retreat without their provision. "This they performed notwithstanding, in good order, retiring from time to time by degrees; and when they had any good opportunity, discharging full Vollies of shot upon the Spaniards."8

1 Alexandre Exquemelin, Bucaniers of America, Part I, 1684, p. 85-6; 2 Exquemelin, Part III, p. 4; 3 Exquemelin, Part III, p. 84; 4 Exquemelin, Part III, p. 87; 4 Exquemelin, Part III, p. 100-1; 6,7,8 Exquemelin, Part II, p. 110

Golden Age of Piracy Sailors Hunting Food

As the chart at the beginning of this section shows, there is at least one example of hunting from every type of sailor. There is only a single example of hunting from the naval accounts. Ship's surgeon John Atkins explains that while serving on HMS Swallow, they stopped at Cape Lopez (in what is today Gabon, Africa) where the savannahs were "the resort of Buffaloes; I have seen a dozen head at a time here, which, when you are minded to hunt or shoot, the Negroes are ready to assist."1 This would not have been to supply food for the ship, however, making it the weakest example of hunting in these accounts. Instead, it seems to have been as much to satisfy the itch to hunt as to provide food. The meat may still have been cooked and served, although this would probably have been the purview of the officers on the ship rather than the before-mast men.

Spitzbergen Harbour, From Spitzbergische oder Groenlandische, By Friderich Martens (1675)

The first merchant account of hunting is fairly straightforward, coming from sailor Alexander Hamilton who spent decades in the East Indies. He explains how, when their merchant vessel arrived at Rembeng, Java the sailors were able to go ashore to purchase food and hunt. "[W]ild Hog and Deer we killed daily with our Fowling-pieces, as we did also Peacocks and wild Poultry."2 It is interesting that he specifies the use of guns intended for hunting here.

Some more unusual hunting entries come from the journal of German surgeon Johann Dietz who was on the whaling vessel Hope of Rotterdam when it stopped at Spitsbergen, Norway around 1690. Dietz explained, "Our men, hunting, for amusement, among these lesser islands, collected their eggs [wild geese, pheasants, kingfishers and others] and ate them. ...We ate these eggs every day... We also shot a great number of geese, ducks and other edible birds."3 While there, the crew also "went reindeer-hunting. Twenty-two men of our ship's crew were provided with flint-locks, balls and powder."4 Dietz reported that the meat "tasted mighty good."5

Fowling in New England, From Naaukeurige versameling der

gedenk-waardigste zee en land-reysen na Oost en West-Indien (1707)

The one privateer account of hunting comes from John Wood's account of the Captain John Narborough's expedition to explore South America in 1670. In the winter of that year, Narborough's ships Sweepstakes and Batchellor Pink stopped at Puerto San Julián,

Chile where Wood reports "we had very good Diversion in the Hunting, Fishing, Fowling, especially in Frosty Weather; For then we met with plenty of Brand-Geese, Ducks, Widgeons, Plovers, Snipes, Sea-Fowls, Partridges, and several other sorts"6.

Dampier provides 5 of the accounts of buccaneers hunting. The first occurred in 1681 when captains Jan Willems ('Captain Yanky') and William Wright landed some men at Point San Blas, Panama (near the San Blas Islands). There, "some of us went ashore every day to hunt for what we could find in the Woods: Sometimes we got Pecary, Warree [hogs], or Deer; at other times we light on a drove of large Monkeys, or Quames, Corrosoes, (each a large sort of Fowl ) Pidgeons, Parrots, or Turtledoves. We liv'd very well on what we got, not staying long in one place"7.

Like privateer Wood, Dampier next mentions sailors hunting at Puerto San Julián. While there in February, 1685, some of the sailors on Captain Edward Davis' ship Revenge "did every day go over in Canoas to them [islands nearby] to Fish, Fowl or Hunt for Guanoes [iguanas]"8. The Revenge had gotten to the Chamela Islands in Mexico by late December, where they "made towards the Valley Valderas to hunt for Beef"9.

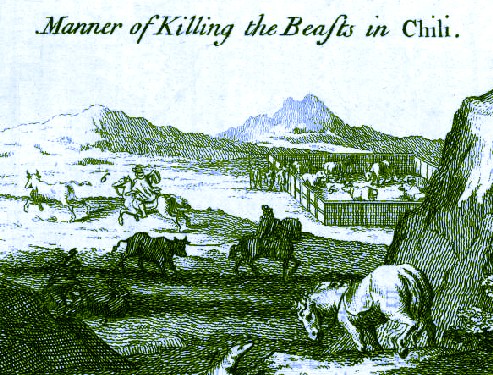

Hunting Cattle in Chile, Relación histórica del viage a la America meridional, Antonio de Ulloa (1772)

staying for seven days to hunt. Dampier says, "Here we kill'd and salted above 2 months meat, besides what we spent fresh; and might have kill'd as much more, if we had been better stor'd with Salt."10 This account is one of the few to specifically state that they ate some of the meat fresh as well as salting some for later use, although it seems logical that most ship-based hunters would have the same. It also points out the importance of a supply of salt on voyages in unfriendly territory.

In March of 1686, Dampier left the Revenge to join the crew of the Cygnet under the command of Charles Swan. After some trips around the Americas, they sailed across the Pacific to the East Indies, arriving at Mindanao in the Philippines in June of 1686 and staying for months. In December, Dampier reported that he had gone "Hunting with the General [sultan of Mindanao] for Beef, which he had a long time promised us"11. After six months at Mindanao, some of Swan's fellow buccaneers grew weary of being stuck there and took the ship in January, 1687, tricking Dampier into joining them while leaving Swan behind. On February 18, they were at Mindoro, Philippines where they attempted to resupply their provisions by hunting. However, as Dampier explained, "we saw great tracks of Hogs and Beef; and we saw some of each, and hunted them; but they were wild, but we could kill none."12

Artist: Caspar Luyken

Party Coming Ashore in a Boat, From Dampier's Nieuwe

reistogt rondom de wereld, (1698)

The last account of buccaneers hunting comes from William Ambrosia Cowley, who, like Dampier, was also aboard the Revenge when it stopped at Chagui, Columbia in 1684. In an aside to a story about the local natives setting fire to one of their boats, Cowley explains that their "Long-Boat [was] gone on shoar to get Beef, whilst they were hunting"13. Since his focus is on the story of the attack on the ship, he doesn't provide any other details of that hunting expedition.

What the accounts of pirates hunting for their food lack in number, they make up for in variety. Each of the instances of pirates hunting food concern a different crew. The earliest example of pirates hunting comes from the exploits of Thomas Howard when he was on the west side of Madagascar around 1700. Chronicler Charles Johnson notes, "They had here plenty of Fish and wild Hogs, which they found in the Wood."14

A second example of hunting on Madagascar comes from the time that pirate Edward England's crew spent there around 1720. Johnson says, "They sent several of their Hands on Shore [at Madagascar] with Tents, Powder, and Shot, to kill Hogs, Venison, and such other fresh Provision as the Island afforded"15. The detail about tents is interesting; it is clear from the text that they intended to stay there for some time which would have made hunting an obvious method for procuring food.

Among the Atlantic pirates there are

New World Encampment in Spanish America, From Sechster Theil, Levinus Ulsius, (1626)

some examples of hunting as well. While at Brazil around 1719, Edward Condent "sent some of his Men ashore to kill some wild Cattle, but they were taken by the Crew of a Spanish Man of War"16. Although the hunters weren't successful in this account, it is at least clear that they pirates intended to rely on hunting to supply some of their food.

The final example comes from George Lowther's crew, who fled to an inlet in North Carolina in August of 1722 after suffering defeat in an engagement with a merchant vessel (the Amy) which resulted in them running their ship Ranger aground. Johnson here explains that Lowther "and his Crew laid up all the Winter, and shifted as well as they could among the Woods, divided themselves into small Parties, and hunted generally in the Day Times, killing of black Cattle, Hogs, &c. for their Subsistance, and in the Night retired to their Tents and Huts, which they made for Lodging"17. Here again, the duration of the stay resulted in the erection of tents, suggesting hunting was something engaged in where the pirates stayed at a place for some time.

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 197; 2 Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, p. 419; 3 Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 131-2; 4 Dietz, p. 133; 5 Dietz, p. 135; 6 John Wood, "Captain Wood's Voyage Through the Streights of Magellan, &c.", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1699, p. 95; 7 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 69; 8 Dampier, p. 177; 9 Dampier, p. 259; 10 Dampier, p. 260; 11 Dampier, p. 364; 12 Dampier, p. 382; 13 William Ambrosia Cowley, "Cowley’s Voyage Round the Globe", A collection of original voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1993, p. 14; 14 Daniel Defoe [Captain Charles Johnson], A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 491; 15 Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 118; 16 Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 583; 17 Defoe [Charles Johnson], p. 315