Obtaining Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Obtaining Food at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Obtaining Food at Sea in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries - Purchasing (cont'd)

Privateers and Buccaneers

Privateers and buccaneers operated in similar ways, each having a letter of marque permitting them to take the ships and cargo of designated nations during their journey. Being under some restriction as to the types of vessels they could take, both needed to purchase food for their journeys when dealing with friendly ships and nations not covered by their letter of marque. Still, these two categories combined make up less of the total number of food purchases found in any of the other three categories with 6 instances of buccaneers buying food (6% of the total) and 13 instances of privateers (12% of the total).

All of the examples of buccaneers buying food

Cartographer: Jacques Bellin - Bay of Sierra Leone [Sherbero is on the Left] (c. 1750)

which are included here occur in the decade before the beginning of the golden age of piracy. Four of them come from William Dampier's first book and the other two are from William Ambroisia Cowley's book, with each on a journey which took their author around the world. Both operated on ships attacking Spanish vessels and colonies in South America, after which they sailed across the Pacific Ocean to Guam, then on to the East Indies, around Africa and home to England. Only one of the five examples of the buccaneers purchasing food comes from outside of the Orient. This is occurs when Dampier was at Sherbero, an Island off Sierra Leone, Africa aboard the Revenge in 1683. (Cowley was actually on the ship at this time as well, although he doesn't mention buying food here.) Dampier explains, "we went thither to them [the natives at Sherbero] several Times, during the 3 or 4 Days of our stay here, to refresh our selves; and they as often came aboard us, bringing with them Plantains, Sugar-Canes, Palm-wines, Rice, Fowls, and Honey, which they sold us."1

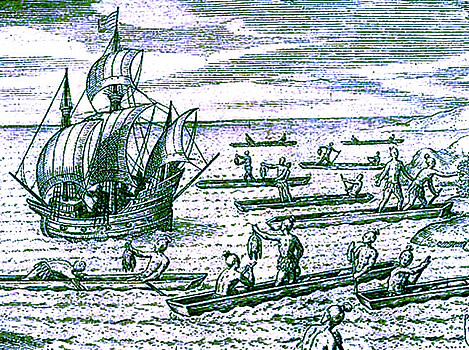

Artists: Johann & Theodor de Bry

Indigenous People Trading With Ship, From Amercae, Part 8 (1625)

The rest of the examples of buccaneers purchasing food come from their voyages through the Orient after crossing the Pacific.

Both of Cowley's citations are from the period after Dampier left the Revenge to join John Eaton's ship Cygnet in August of 1684. Eaton arrived at Guam in early 1685 where Cowley reported that the natives "came on board us, and brought us Potatoes, Monanoes, Cocoa Nuts and Plantans"2. In his second example, Cowley describes the Cygnet arriving at Borneo where the locals "brought us Fish in great plenty, with Oranges, Lemons, Mangoes, Plantains and Pine-Apples; besides which, and many more things, here an abundance of excellent Bezar Stones, some Musk, Civette, &c."3

Dampier gives a great deal of information on how trading worked on the Philippine Island he called 'Orange', which is today named Itbayat in the Batanes, north of Luzon. Once the crew of the Cygnet had landed in their canoe,

Artist: Caspar Luyken

From W Dampier en L Wafer Reistogten Rondom de Waereld (1717)

the Natives brought aboard both Hogs and Goats to us in their own Boats; and every Day we should have fifteen or twenty Hogs and Goats in Boats aboard by our side. ...Beside the fore-mentioned Commodities, they brought aboard great quantities of Yams and Potatoes... We did commonly furnish our selves with as many Goats and Roots as served us all the Day; and their Hogs we bought in large quantities, as we thought convenient; for we salted them. Their Hogs were very sweet; but I never saw so many Meazled ones.4

Dampier's other two examples of purchasing food in the Orient both come from Pulau Bouton, Indonesia when they stopped in December of 1687. The first gives another example of how food purchases were carried out: "...in the Morning betimes a great many Boats and Canoas came aboard, with Fowls, Eggs, Plantains, Potatoes &c, but they would dispose of none till they had Orders for it from the Sultan, at his coming."5 He goes on to explain that the sultan came aboard at 10am. The second example details a purchase of "about a Thousand Pound Weight of Potatoes."6 This is quite a bit of perishable food, presumably bought when they were leaving. Although other food purchases are not detailed, they were there for twelve days and Dampier's list suggests that other food items were likely purchased.

Like the buccaneers, the three privateering voyages were made to South America, eventually crossing the Pacific and going to the orient. Of the 13 privateering instances, 10 of them are from Woodes Rogers' voyage which began aboard the Duke and Dutchess leaving Bristol in August of 1708 and finished with their arrival in the Thames in October of 1711.

Artist: William Hogarth - Woodes Rogers (1729)

There are two different accounts of the voyage, one from Rogers, captaining the Duke, and the other from Edward Cooke, second Captain of the Dutchess.

Rogers only mentions purchasing food at São Vincente in the Cape Verde Islands in October of 1708 on their way to South America. He does so on two occasions, once on October 3rd when they procured food "in Truck [exchange] for our Prize-Goods what we wanted; they having plenty of Cattel, Goats, Hogs, Fowls, Melons, Potatoes, Limes, ordinary Brandy, Tobacco, Indian Corn, etc."7 Three days later, Rogers reported that "there came another Boat ... [which] brought Limes, Tobacco, Oranges, Fowls, Potatoes, Hogs, Bonanoes, Musk and Water-Melons, and Brandy, which we bought of him, and paid in such Prize-Goods as we had left of the Bark’s [a prize vessel] Cargo cheap enough."8

Cooke's account of the voyage contains the majority of the instances of privateers purchasing food. When Rogers' ships arrived at Atacames, Ecuador in August of 1709, Cooke explains that the ships "sent our Interpreter, and a Spanish Captain [who was a captive], to know whether they would trade, and we would pay them for all we had, or else would burn their Houses."9 Not surprisingly, the Spaniards agreed to trade rather than let the privateers destroy their village, so some cattle and plantains were purchased there.

Many of the rest of Cooke's accounts of purchasing food come from the East Indies, presumably because the privateers simply chose to take what they needed

The Duke and Dutchess, From A New Universal Collection of Authentic Voyages and Travels,

By Edward Cavendish Drake (1769)

while sailing in South America. Arriving at Pulau Bouton in May of 1710, they found the inhabitants "came off with Indian Corn, Coco-Nuts, Patats, Papas [Paw paws, Asimina triloba], Hens, and pretty Indian Birds, to truck [trade]"10. They anchored three leagues (about 10 miles) from Pulau Buton, where they were "trading with the People who came off in Boats, bringing Fowl, Corn, Rice, Plantans, Beans, Arrack &c."11

About a month later, the ships were anchored at Madura Island off Java where Cooke says "we had Liberty of all the Markets, and the City, to buy what we pleas’d; but found it very hard to get salt Provisions, which oblig’d us to kill several Bullocks, and pickle the Flesh, taking out all or most of the Bones. Arrack, Rice, and Fowls, were cheap enough."12 By October of that year, they had only managed to get to 'Java Head' (Tanjung Layar, West Java) where they "sent several Men with Arms and Provisions to Pepper Bay, to buy Fowls and fresh Provisions"13.

From there, they began making their way home to England, stopping at the Dutch-held Cape of Good Hope, Africa in December where "Flesh, Corn, Wine, Fruit, Sallads, and other Provisions, [are] as plentiful and cheap as in Europe, besides excellent Water"14. Upon reaching Fair Isle, Scotland in July of 1711, a Dutch squadron commander signalled the privateers, as a result of which "all the [privateer] Captains went aboard him, and he offer’d Capt. Courtney to supply our Ships with Beer, and any other Things we had aboard to spare [us]."15 (Although not specifically stated, this was likely offered for trade or purchase by the Dutch navy vessels, which included victualling ships.) They made their way to Shetland where "the Inhabitants of Shetland, who are North Britains, came aboard every Day, in Norway Yaules, bringing fresh Provisions to sell, and very cheap."16

Cartographer: Nicholas Bellin - View of the North Entrance to St. Catherine's Island, Brazil (1748)

Of the remaining three accounts of privateers buying food, two come from George Shelvocke's eight week stay at Santa Catarina Island off the coast of Brazil in 1719. At the beginning of the stay on June 23rd, Shelvocke explains, "the Captain of the Island, and the rest of the inhabitants came off to us every day, with the product of the place"1.7 Nearer to the end of their stay on August 16th, he says "I purchas'd 21 head of black cattle... together with 150 bushels of Farina de Pao, which is the flower of Cassader [cassava] root, as fine as our oatmeal... [and] I likewise bought 160 bushels of calavances [hyacinth beans]"18

The last example of privateers purchasing food is also from Brazil, given in the account by William Funnell who was aboard the St. George. The ship stopped at Tacames in 1704 where there were "Indian People, who sell to the Spaniards, when they come here, all sorts of Fruits, as Coco-nuts, Plantains, Bonanoes, &c."19

1 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 78; 2 William Ambrosia Cowley, "Cowley’s Voyage Round the Globe", A collection of original voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1993, p. 18; 3 Cowley, p. 25; 4 Dampier, p. 435-6; 5 Dampier, p. 455; 6 Dampier, p. 458; 7 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 25-6; 8 Rogers, p. 27; 9 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World in the Years 1708 to 1711, 1712, Volume 1, p. 299; 10,11 Cooke, Volume 1, p. 449; 12,13 Cooke, Volume 1, p. 451; 14 Cooke, Volume 1, p. 452; 15 Cooke, Volume 1, p. 454; 16 Cooke, Volume 1, p. 455; 17 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 19; 18 Shelvocke, p. 51-2; 19 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 60

Pirates - Legitimate Food Procurement

Given the popular image of pirates as clever marauders and thieves of the sea, it may be surprising to some that there are 25 accounts of pirates purchasing food. To be fair, 6 of these describe them forcing a ship to trade for what were likely unwanted items in order to give their theft the veneer of legitimacy. Yet this still leaves 17 examples of pirates actually purchasing food during their journeys. Of course, they were usually trading with stolen money and goods, but the vendors either didn't know or didn't care that this was the case. As for the pirates, some times it was just easier to purchase food -

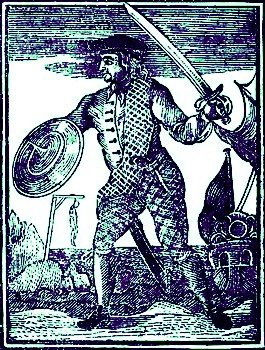

Pirate Henry Every (17th c.)

there may not have been any prize ships with food aboard in the offing or they didn't want to draw attention to themselves when coming to legitimate ports. The mix of pirates purchasing food included here is fairly broad, containing twelve different pirate crews along with two instances where the identity of the crew is not known.

The earliest and most often-mentioned golden age pirate to purchase food in these accounts was Henry Every sailing on the Fancy in 1694 and 1695. At trial, crew member William Phillips testified to Every purchasing food in four different places on his way to the East Indies after inciting a mutiny in Corunna, Spain. Every stopped at 'Princes' (Principe) off the West Coat of Africa, where "we took in here some rum and Sugar and fresh Provisions which we bought of the Inhabitants and paid them for."1 Phillips said that a month later they moved on to Annobόn, where "we took in more water and Oranges and about fifty hogs which we paid for part money, part small arms."2 They then sailed around Africa, stopping along the way at Madagascar where "we bought about 100 bullocks for powder and small arms."3 Phillips said they stayed there 'about a month' and then made their way to 'Johanna' [Anjouan, now Ndzwani in the Comoros Islands]. "There we bought some hogs and paid for them"4, apparently with money, although this is not made clear here. Another crewman, Benjamin Franks, testified that in 1695 Every's crew returned to 'Johanna' to recruit some water. The natives refused to give it to them, so "our Captain next morning sent both Boats with a matter of 40 Men or thereabouts with Armes... and ...bought two Cowes and some dates”5.

Artist: Willem Van de Velde the Younger

The Charles Galley, Similar to Kidd's Adventure Galley (late 17th c.)

William Kidd appears second most-often in this list with four different purchases of food. The first is when he stopped at Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands in his ship Adventure Galley, probably in late 1696. Of this, Kidd simply said, "there we bought Provisions". The next site where he mentions purchasing victuals was at Madagascar in February of 1697 where he gives a similarly terse description.6 Up to this point, he was still considered a legitimate pirate hunter rather than a pirate. After he had turned pirate, Joseph Palmer testified at Kidd's trial that "he bought some Hogs of the Natives"7 at Mararikkulam, India in 1698. He then sailed to 'Porca' on the Indian coast [probably near modern Alappuzha, India] where he procured more pork. Charles Johnson stated that he used the cargo taken from the Quedagh Merchant in January of 1698 to trade for provisions at other coastal towns on the Indian coast.8

A couple other pirates active in the East Indies purchased food as well. Dirk Chivers was in charge of the pirate vessel Resolution which stopped at 'Sukkotre' (Sokatra, Yemen) around 1696 "where they bought provisions."9 In 1701, pirate William Read sailed to Mayotte in the Comoros Islands where Johnson reports "they took in a Quantity of fresh Provision, which is in this Island very plentiful, and very cheap."10 Unfortunately, while there, Read died and the command was given to a Captain James, who was eventually replaced by John Bowen.

Kochi, From The Capture of Kochi by the Dutch 1656, Atlas van der Hagen by Coenraet Decker (1682)

Two years later, Bowen was sailing the Speedy Return and Thomas Howard was in the Prosperous. The pair stopped at Kochi, India where "they anchored and fired several guns, but no [supply] boat coming off, the quartermaster went near the shore and had conference by boat with the [local] people, who supplied them next day with hogs &c refreshments."11

The last recorded instance of pirates purchasing food from the East Indies in the documents under study was almost twenty years later in 1720. John (Richard) Taylor, captain of the Cassandra, had made after several attempts to procure in India before they sailed for Kochi. "At night there came on board a large boat laden with fresh provisions and liquors with the servant of an inhabitant of that place, vulgarly called John Trumpet who told them they must immediately weigh and run further to the southward, where they should have a supply of all things they wanted, as well Naval stores and provisions."12

There are a couple of examples of pirates who were active in the Americas

Artist: Lionel Wyllie

The Bahamas, From The Merchant Vessel, By Charles Nordhoff (1884)

purchasing food as well. One of the earlier examples of this comes from official records detailing the behavior of the 'flying gang' pirate consortium which included Benjamin Hornigold, Henry Jennings, Josiah Burgess, Edward Teach and a Captain White. In July of 1717, Captain Mathew Musson wrote the Council of Trade and Plantations that at Harbor Island in the Bahamas there "were there two ships of 90 tons which sold provissons to the said pirates, the sailors of which said they belong'd to Boston".13 The Bahamas became something of a food stop for Caribbean- and American-based pirates during this period, something which is discussed in greater detail in the article on provisioning stations.

That same year, Stede Bonnet brought his ship Revenge to New York where he "landed some Men at Gardner’s Island, but in a peaceable Manner, and bought Provisions for the Company's Use, which they paid for, and so went off again without Molestation."14 This was early in Bonnet's career, which may explain why he used legitimate means to get food.

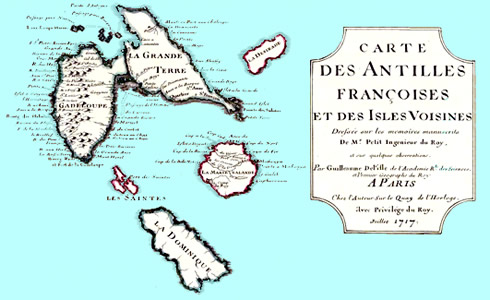

Cartographer: Guillaume de L'Isle

Guadalupe, La Désirade, Marie-Galante Iles des Saintes & Dominica (La Dominique),

From Carte des Antilles

Francoises et Les Isles Voisines (1731)

Bartholomew Roberts is directly mentioned purchasing food once at 'Dominico' (Dominica in the French West Indies) in 1720 where he "got Provisions of the Inhabitants, to whom he gave Goods in Exchange."15 A second mention of Roberts procuring food occurs at Annobón in 1721, where they "took aboard a Stock of fresh Provisions, and then sailed for the Coast"16. While it is not certain whether the goods were paid for by the pirates, it seems likely from the text. Edward Low anchored at Barbados following a rough time at sea in a storm where the pirates lost many of their provisions; there, "they got Provisions of the Natives, in exchange for Goods of their own"17.

At this time, it was technically illegal for English subjects to sell food and drink to pirates, according to the English Laws relating to such sales. In 1700, under the rule of King William and Queen Anne, a statute was issued (CAP. VII. 'An Act for the more effectual Suppression of Piracy') which in spirit, if not exactly in word, banned English vendors from selling provisions to pirates. The actual wording is a bit redundant and so it is not given here in full, but the relevant section of the Act explains:

Artist: Michael Dahl - Queen Anne (1705)

That all and every Person and Persons whatsoever, who, after the twenty-ninth Day of September in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred, shall either on the Land, or upon the Seas, knowingly or forth, or aiding, wittingly set forth any Pirate, or aid and assist, or maintain, procure, command, counsel or advise any one assisting any Person or Persons whatsoever, to do or commit any Piracies or Robberies ...either on the Land or upon the Sea, shall be and are hereby declared, and shall be deemed and adjudged to be accessary to such Piracy and Robbery done and adjudged committed ...[those convicted of such] shall suffer such Pains of Death, Loss of Lands, Goods and Chattels, and in like Manner, as the Principals of such Piracies, Robberies and Felonies ought to suffer18

The key words in the act which could be extended to supplying food were 'aid' and 'assist'. This Act was created to be in force for seven years, but was extended under the reign of Anne twice - in 1706 and 1713.19 Nearing its third anniversary, the act was expanded and made more explicit by King George I in CAP. XXIV, 'An Act for the more effectual suppressing of Piracy':

That if any Commander or Master of any Ship or Vessel, or any other Person or Persons, shall from and after the twenty-fifth Day of March which shall be in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and twenty-two, any wise trade with any Pirate, by Truck, Barter, Exchange, or in any other Mariner, or shall furnish any Pirate, Felon or Robber upon the Seas, with any Ammunition, Provision or Stores of any Kind, or shall fit out any Ship or Vessel knowingly, and with a Design to trade with, or supply or correspond with any Pirate, Felon or Robber upon the Seas… [they] shall suffer such Pains of Death, Loss of Lands, Goods and Chattels, as Pirates, Felons and Robbers upon the Seas ought to suffer20

The Act went on to add, "That every Ship or Vessel which shall be fitted out with a Design to trade with, or supply or correspond with any Pirate, and all and every Goods and Merchandizes put on board the same for any Intent or Purpose to trade with any Pirate, Felon or Robber on the Seas, shall be ipso facto forfeited"21.

1 “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 23-4; 2 “2. William Phillips...', p. 24; 3,4 “2. William Phillips...', p. 25; 5 “71. Deposition of Benjamin Franks. October 20, 1697.”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, 1923, John Franklin Jameson, ed., p. 193; 6 The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Captain William Kidd, 1701, p. 22; 7 The Arraignment, Tryal..., p. 23; 8 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 446; 9 “71. Deposition of Benjamin Franks. October 20, 1697.”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period..., p. 175; 10 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 474; 11 Captain George Wesley, “Extract of a Letter from Captain George Wesley to Mr. Pnnyng, Chief at Calicut, Dated [Râjâpur] , 7 November 1703”, The Indian Antiquary, S. Charles Hill, ed., Volume XLIX, February, 1920, p. 21; 12 Richard Lazenby, “Letter from Richard Lazenby”, The Indian Antiquary, S. Charles Hill, ed., Volume XLIX, April, 1920, p. 57-8; 13 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 29, Item 635; 14 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 96; 15 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 215; 16 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 230; 17 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 322; 18 Great Britain and Owen Ruffhead, Statutes at Large, Vol. 4, (1699-1713), 1763, p. 45; 19 Statutes at Large, Vol. 4, p. 268 & 613; 20,21 Great Britain and Owen Ruffhead, Statutes at Large, Vol. 5, (1714-1728), 1763, p. 410;

Pirates - Less Than Legitimate Food Procurement

Several pirates used a particular brand of trade to force other ships to provide them with food - giving the target ship things they didn't want in exchange for provisions. Charles Johnson suggests that such actions gave the pirates' action the appearance of being a trade rather than outright theft. In June of 1718, Edward Teach was allegedly lying low in Bath, North Carolina after having made a deal for pardon with governor Charles Eden. He couldn't resist the lure of his former trade, however. As Johnson explains, Blackbeard hung around on the river, "trading with such Sloops as he met, for the

Artist: Frank E. Schoonover -

Arrival of Pirates in Town, From Blackbeard: Buccaneer, p. 7 (1920)

Plunder he had taken, and would often give them Presents for Stores and Provisions he took from them; that is, when he happened to be in a giving Humour; at other Times he made bold with them, and took what he liked, without saying, by your Leave ['with your permission'], knowing well, they dared not send him a Bill for the Payment."1

In July of the same year, Teach's former partner Stede Bonnet was using a similar tactic after also having received pardon from Eden. He was a bit more desperate because he had sailed off to pirate and had a crew to feed. From a sloop they had captured off of Cape Henry, Virginia, "Bonnet and Crew took out of her twenty Barrels of Pork, some small Quantity of loose Bacon, and gave him again two Barrels of Rice, and a Hogshead of Molosses [in exchange], and sent her away."2 From a pink captured around the same period which had "a Stock of Provisions on board, which they happened to be in Want of, they took out... ten or twelve Barrels of Pork, and about 400 Weight of Bread; but because they would not have this set down to the Account of Pyracy, they gave them eight or ten Casks of Rice, and an old Cable, in lieu thereof."3 Here, the token-nature of such 'traded' goods is quite clear.

Another explicit example of the motive behind such 'trades' comes from Bartholomew Roberts' trip through Newfoundland in September of 1720, where they they let Robert Dunn, master of the Relief go after "putting on board his sloop some bundles of old rigging and cloth etc. in return for his tending them with turtles etc. which they made him do."4 Nine months later at Falmouth, England a fishing boat " met a Sloop, and sold her as many Fish as amounted to 10 l. [pounds] but instead of paying for them, gave them only two Bottles of Brandy: The said Sloop was suppos’d to be a Pirate newly set out, having upon Deck above 60 Men."5

Pirate Captain John Gow, From The General

History

of the Pirates (1725)

The last example of such a trade comes from the ordinary's account of John Gow. His pirates sailed the Revenge to Porto Santo Island in the Madeiras in 1724 with a desire to procure water and provisions, which the local governor granted them. Unsuspecting, the governor and some of his entourage visited the Revenge where they were treated civilly. After the provisions did not appear in what the pirates felt was a timely fashion, however, the governor's group

were told flatly the Captain [Gow] was not to be trifled with, that the Ship was in want of Provisions, and they would have them, or they would carry them all away… to their great Satisfaction they saw a great Boat come off from the Fort, and which came directly on Board with seven Buts of Water, a Cow and a Calf, and a good number of Fowls.

When the Boat came on Board, and had delivered the Stores, Captain Gow complimented the Governour and his Gentlemen, and discharged them to their great Joy; and besides discharging them, he gave them in Return for the Provisions they brought, two Cerons of Bees Wax, and fired them three Guns at their going away.6

Such behavior really suggests that they were taking goods rather than legitimately purchasing them, but they are included here because the pirates at least paid something for the provisions... whether the other people wanted that payment or not.

1 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 77; 2 “22. David Herriot and Ignatius Pell on Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet, from The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and other Pirates (London, 1719), pp. 44-48”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 101; 3 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 98; 4 CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 32, Item 251. iii.; 5 Weekly Packet, 6-24-21 -7-1, Issue 469; 2 Select and Impartial Accounts of the Lives, Behavior, and Dying-Words Of the most Remarkable Convicts, Vol. II, 1745, p. 220-21