Food Healthiness at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 <<First

Food Healthiness at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Healthiness of the Sailor's Diet, Continued

Healthiness of the Sailor's Diet: Salt Meat (Beef and Pork)

Salt beef and pork were the two staples of most sailor's diets, at least from the point of view of the sailors. Of all the navy-mandated foods, salt meats earned the most complaints from the sailors. (The complaints included here do not include the saltiness of the meat, which has already been discussed.)

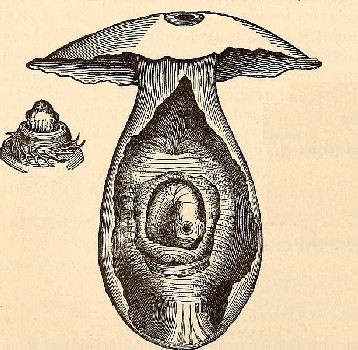

Pork Tapeworm Cyst with Worm Inside, From the Annual

Report of the North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station (1896)

Pork could be particularly problematic because it could be 'measeled', that is, the pig could be infested with tapeworms or bladderworms before being slaughtered. Emily Cockayne explains, "Pork was potentially a more dangerous product than beef it deteriorated more quickly, and carried a greater number of communicable diseases…. Between 1648 and 1687 there were over thirty cases of fines for selling measled swine, with a peak of offences in the 1670s and 1680s."1 Since the sailors' meat leaving from England was packed in brine, any such parasites in the pork would be dead and so unable to infect the sailors. However, when sailors purchased food locally, they could be faced with the problem. Privateer William Dampier notes that while they were trading with the natives of the island of Ibayat in the Batanes (Phillippines) in 1687, "I never saw so many Meazled ones."2

There are a few examples of bad salt meats from sources from just before the golden age of piracy worth mentioning here. While sailing as chaplain aboard HMS Assistance, Henry Teonge mentioned a sort of celebration that the sailors referred to as the 'Last day of Lent' on April 17, 1676, "that is the day whereon the last boiling of the beef that was bought at Cyprus [purchased in October of 1675] was flung overboard, for the meat was so bad that they chose rather to eat bread dry than to eat that meat."3 The Assistance seems to have been cursed with bad meat; five years later Sir Robert Robertson "denounced provisions for his ship, which was serving in the Mediterranean: The beef looked bad before it went into the furnace, but when it came out, ‘twas almost as black as coal and shrunk to nothing. The pork tasted so fishy that the men could not eat it"4. In July of 1689, at the beginning of the War of the League of Augsberg, Edward Russell "reported that in his squadron, the Blue, the seamen only ate when compelled by hunger, many ships were 'extremely sickly' and that 'the beafe proves full of gaules [gall bladders?]"5. While Russell said he didn't think the galls were a problem, "the men fancy 'tis poison, and in my one ship, several men has thrown over their provision"6. He suggested that when they got hungry enough, they would eat whatever they had.

Artist: Annibale Carracci

Meat in a Butcher's Shop (1580s)

A variety of comments about the meat found on ships were recorded during the golden age of piracy, some from the navy, some from privateers and others from pirates. Two of the three comments actually praise the victualling, at least suggesting an improvement in the victualling process from the previous decades.

Among the naval accounts mentioning the healthiness of meat is one from Rear-Admiral John Jennings who had been ordered to survey the meat which had been sent to the Victualling Office for the navy's use in 1706. He reported that "the beef and pork is very fat and well packed up; as indeed I must own myself that the provisions our men are served with twice a week is extreme good."7 A year later, Sir Cloudsley Shovell praised the fresh meat brought to his ship Association at Oiras [the mouth of the Tagus] by the victualling agent in Lisbon which, as mentioned previously, he said "has been a great preservative and much contributed to the health of our seamen."8 Not all naval commentaries were so positive, however. In 1709, navy cook Barnaby Slush said that "the Beef, which goes through my Hands; which, oftentimes, carrys such an ineffable Hogo [unpleasant smell] with it, that verily, I should never be able to bear"9. (He does note that the smell had the side benefit of driving the rats away from his quarters.)

Merchant ships and privateers sailing for long periods were also exposed to problems the came with the extended use of salt meats. In 1722, Clement Downing aboard HMS Salisbury channeled Slush's comment, explaining,

We had on board two Casks of English Beef, which stunk to such a degree, that our Captain could not bear his Cabin. We complained of this, but did not meet with any Relief; which very much disheartened and sour'd our Ship's Crew: Why we were forced to eat such Meat, was to us very strange, for at Madagascar we could buy fine Bullocks for a Dollar a head10

Privateer Woodes Rogers noted that in October 1709, they could no longer rely on "our old Food of almost decay’d Salt Pork and Beef"11. This should not be entirely surprising; the voyage had begun in England in August of 1708, making their store of salt meats more than a year old.

All the pirate accounts mentioning bad salt meat are found in accounts from the East Indies. The first is from John Hoar's ship John and Rebecca which was in the Persian Gulf in 1695. According to witness Henry Watson, the pirates had stopped at what is probably today called Greater Tunb island

Photo: Wolfang Sauber

Barrels of Supplies in the Vasa Warship Model

where they killed and ate antelopes, "until being weary of that kind of flesh and having nothing but stinking beef and doughboys (that is dough made into a lump and boiled) they weighed anchor"12. Nathaniel North, sailing in 1701 mentioned that "the Provisions they had salted up at Madagascar not being well done, it began to spoil"13. Such victuals would have been killed on the mostly undeveloped island of Madagascar where it had to be salted as well as the pirates could manage. In 1703, pirate John Bowen's crew of the Speedy Return were near India when they found "their Salt Provisions perishing, [so] they return’d to Madagascar to revictual".14

With regard to the perceived health of meat, modern historian Andrew Wear says "Animals were judged to be healthy (hence to be healthy food) ...animals and fish coming from the wild were equated with health and cleanliness."15 Naval physician William Cockburn's opinion on salt-meats sort of see-saws. On the one hand, he explains that "salt victuals have been found, by experience, the worst of all others to digest; and Sunctuorises, in his book of Statical Medicin [De Statica Medicina (1614) by Italian physician Santorio Santorio], has declared, that they are the victuals by which we perspire least; and still less by Pork than the rest, and so, by the laws of perspiration, it must be concluded to contain the grossest juices and the worst nourishment"16. Perspiration was felt to be a way to remove unconcocted or 'gross' humors from the body according to humoral theory. So if salt-preserved meats retarded it, they would work against the bodies attempt to process food effectively. However, Cockburn goes on to state that salt meats were "necessary for their [the sailor's] toyl and labour, and that [sort of food] which is finer and more easily digested, would not prove of long enough continuance for their work"17.

Thomas Tryon, although himself a vegetarian, supported the use of salted meat in some diets. He explained that the meat of oxen (as opposed to that of cows) is "naturally clean and wholsom if such Cattel be free from Diseases and Surfeits [eating too much]; it generates a strong firm Nourishment, having a greater affinity with mans Nature than with any other"18. However, he also warns that ox meat was hard to concoct [process into chyle and humors] and "therefore ought to be eaten sparingly, except by strong working People... It ought not to be eaten until it be well season'd with Salt, or if eaten fresh, there ought to be good store of Salt eaten with it, and boiled in plenty of Water"19.

Photo: Alexandr Frolov - Fierce, Savage and Unclean

Pigs in the Altai Mountains

Tryon's view of pork was less enthusiastic. He accused hogs of having a humoral "Complexion Melancholy and Cholerick, their predominant Quality stands in the fierce, savage and unclean Nature"20. He noted that it was a popular meat in England, but at least the English prepared it better than they otherwise might, by choosing how it was treated and fed. "That Bacon or Pork which is fed with Corn and Acorns, and have their liberty to run, is much sweeter and wholsomer, easier of digestion, and breeds better blood than that which is shut up in the Hog-sties, such Bacon for want of Motion becomes of a more gross phlegmatick Nature."21 Like beef, pork was also best eaten when it was well-salted in his opinion.

1 Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, 2007, p. 95; 2 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 436;

3 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 138; 4 "TNA, ADM 1/3551, fo. 79", cited in J.D. Davies, Pepys’s Navy, 2008, p. 202; 5 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 173; 6 NAM Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 192; 7 "22. Rear-Admiral Sir John Jennings to Victualling Board, Plymouth, 14th December 1705", cited in Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 277; 8 "24. Admiral Sir Cloudsley Shovel to Victualling Board, From on board the Association in the Bay of Wares, 27th December 1706", cited in Merriman, p. 279; 9 Barnaby Slush, The Navy Royal, Or a Sea Cook Turn'd Projector, 1709, p. 66; 10 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 91; 11 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 277; 12 Henry Watson, “37. Henry Watson, from Narrative of Mr. Henry Watson, who was taken prisoner by the pirates, 15 August, 1696”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 177; 13 Daniel Defoe (Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 516; 14 Defoe (Charles Johnson), p. 496; 15 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 142; 16,17 William Cockburn, An account of the nature, causes, symptoms, and cure of the distempers that are incident to seafaring people, 1696, p. 6; 18 Thomas Tryon, The Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness, 1697, p. 57; 19 Tryon, p. 58; 20 Tryon, p. 66; 21 Tryon, p. 67

Healthiness of the Sailor's Diet: Other Foods

Once the standard preserved food sailor's diet had run out, ships could (and, depending on where they were, sometimes had to) resort to eating local food. One of the problems with local foods was that the food may not have been healthy for various reasons.

Tropical fish can contain cinguatoxin and, when eaten, can cause a type of food poisoning called cinguatera. This is explained in some detail in the discussion of fish in the Animal Bites and Stings article, which also

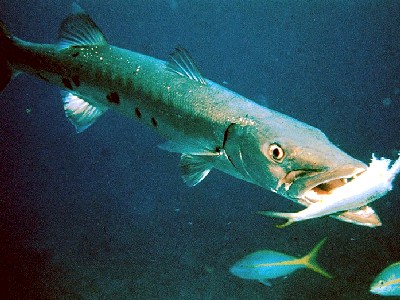

Photo: Florida Keys Marine Sanctuary - Barracuda With Prey

provides two accounts of what is almost certainly cinguatera poisoning, one from the travels of privateer William Dampier and the other from pirate Nathaniel North.

There are two other accounts that are likely cases of this type of fish-borne poison. The first comes from Dutchess captain Edward Cooke's account of privateer Woodes Roger's voyage from December 27, 1709. Anchored off of Cabo San Lucas, Cooke explains that "we had several of our best Men poison’d with eating some Fish, and [they were] scarce able to stand... but the Doctor gave them something, and they soon recover’d."1 It is unfortunate that the type of fish isn't listed. Another privateer, sometime surgeon Lionel Wafer, explains that he had known several sailors who were poisoned by eating barracuda "to that degree as to have their Hair and Nails come off; and some have died with eating them."2 He also says that numbness of the limbs and weakness can result. While barracuda is known to carry cinguatoxin, loss of hair and nails are not actually symptoms of this poison. Paralysis is and death can result, although it is unusual. Wafer mentions that he has been told the antidote to such poisoning was the powdered backbone of the fish, although he stops short of certifying this.

, Ecuador, Wiki Soler97.jpg)

Photo: Wiki User Soler97 - Nazca Booby Flying, Ecuador

William Funnell's account contains a few animals he felt caused illness from his privateering account of South and Central America in 1703 and 1704. The first he mentions is the booby, of which he said he had eaten many, noting that they "taste very Fishy; and if you do not salt them very well before you eat them, they will make you sick"3. Another animal he tried while at Costa Rica was an iguana which he referred to as a 'Guano'. "When they are stewed with a little Spice, they make good Broth; and the Flesh looks very white, and eats very well; but if they are not extraordinarily well boiled, they are very dangerous to eat; making Men very sick, and often putting them into a Feaver, as we were informed by our [Spanish] Prisoners."4 Iguanas are known to be carriers of salmonella which can be transmitted when the meat is under cooked. Among other things, it causes abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.5

Woodes Rogers said that eating the liver of a seal in March of 1709 killed one of his Spanish sailors 'suddenly' while at an island he called Lobos located near Lima, Peru. As a result, Rogers "forbad

Photo: Mirko Thiessen - South American Fur Seals (The Type Found in Peru)

the use of ‘em. Our Prisoners told us, they accounted those old Seals very unwholesom."6 It is not clear that seal liver was in any way toxic, but Rogers was in Spanish-held South America and needed to keep as many of his men healthy as he could. Rogers also noted that they gave off an "ugly noisom Smell ...which gave me a violent Head-Ach, and every body else complain’d of this nauseous Smell."7 He noted that the seals they had previously encountered (and eaten) on Juan Fernandez did not have this effect.

While fresh fruit was mostly regarded as healthy, in some cases it had a less than sterling reputation. Sea surgeon John Moyle noted that "eating of much raw Fruit, or other vitrious Diet; that makes fit matter for Worms to Generate."8 Physician William Cockburn blamed eating "early and unripe Fruit" for causing Diarrheas.9 He elsewhere explains, "It is the Experience of every Country, that unripe Fruit very commonly causes a Diarrhea. Even Countries not otherwise subjected to the Disease, feel these Effect of Fruit in the Season."10

One type of fruit whose healthiness was heavily criticized in the buccaneering accounts from the late 17th century was that of the manchineel tree. Alexandre Exquemelin leads the accusations in his account.

Photo: Wiki User Mica - Manchineel Trees

The tree called Mancanilla, or Dwarf apple-tree, groweth nigh unto the Sea Shoar; being naturally so low, that its branches, though never so short, do always touch the water. It beareth a fruit, something like, unto our sweet sented apples; which notwithstanding is of a very venemous quality. For these apples being eaten by any person, he instantly changeth colour, and such an huge thirst doth seize him as all the Water of the Thames cannot extinguish, he dying raving-mad within a litle while after. But what is more the Fish that eat as it often happeneth, of this fruit are also poysonous.11

He goes on to say that after "being hugely tormented with Mosquitos or gnats, and as yet, unacquainted with the nature of this tree, I cut a branch thereof, to serve me instead of a fan; but all my face swelled the next day, and filled with blisters, as if it were burnt to such a degree, that I was blind for three days."12

Another comment about manchineel fruit can be found in the second part of the same book, which is largely attributed to buccaneer Basil Ringrose. However, this quote is not found in Ringrose's original manuscript, so it is not clear who wrote it. The author explains "as I was washing my self, and standing under a Manzanilla-tree, a small shower of rain happen'd to fall on the tree, and from thence dropped on my skin. These drops caused me to break out all over my body into red spots, of which I was not well for the space of a week after."13

The final report on the manchineel fruit comes from buccaneer surgeon Lionel Wafer. "‘Tis in Smell and Colour like a lovely pleasant Apple, small and fragrant, but of a poisonous Nature; for if any eat of any Living Creature that has happen’d to feed on that Fruit, they are poisoned thereby, tho’ perhaps not mortally."14 He adds that "the very Sap being so poisonous, as to blister the part which any of the Chips strike upon as they fly off."15 By way of illustration of these properties, Wafer says,

A French-man of our Company lying under one of these Trees, in one of the Samballoes [San Blas Islands, Panama], to refresh himself, the Rain-water trickling down thence on his Head and Brest, blistered him all over, as if he had been bestrewed with Cantharides [Spanish fly wings, a blistering medicine]. His Life was saved with much difficulty; and even when cured, there remained Scars, like those after the Small-Pox.16

Photo: Dick Culbert - Manchineel Fruit (Hippomane mancinella) This account sounds like the one found in the section of Exquemelin's book which is generally attributed to Ringrose. Ringrose was English, not French, which may explain why this account of the manchineel poisoning doesn't appear in his original manuscript. So the identify of the writer of this account is still not clear.

George Parker Winship, who edited the 1903 edition of Wafer's book explains in a footnote: "The sap of the manchineel is very injurious to the eyes, but otherwise not as dangerous, at least not to persons in good health, as the above [comments by Wafer] would imply."17

In contrast, radiologist Nichola Strickland wrote a modern account of what happened when she and a friend ate a manchineel apple while in Tobago. She says that it first tasted sweet, but then "we noticed a strange peppery feeling in our mouths, which gradually progressed to a burning, tearing sensation and tightness of the throat. The symptoms worsened over a couple of hours until we could barely swallow solid food because of the excruciating pain and the feeling of a huge obstructing pharyngeal lump."18 Fortunately, their symptoms receded over the next eight hours. This led her to research the toxicity of the tree, from which she learned that the sap of the tree "causes blistering, burns, and inflammation when in contact with the skin, mucous membranes, and conjunctivae [mucus membrane of the eye]."19 She notes that the most common result is 'contact dermititis' which is in line with some of the descriptions given by the buccaneers. While it does not appear to be quite as deadly as Exquemelin suggested it could be, it is not as harmless as Winship suggests.

1 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World in the Years 1708 to 1711, 1969, p. 333; 2 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 127; 3 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 10; 4 Funnell, p. 76; 5 Mayo Clinic Staff, Salmonella infection, mayoclinic.org, gathered 9/19/19; 6,7 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 149; 8 John Moyle, Chirugius Marinus: Or, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 254; 9 William Cockburn, The nature and cures of fluxes, 4th ed., 1724, p. 57; 11 Alexandre Exquemelin, Bucainers of America, 1684, p. 39-40; 12 Exquemelin, p. 40; 13 Exquemelin, Second Section, p. 44; 14 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 100; 15,16,17 Wafer, p. 101; 18,19 Nicola H. Strickland, "Eating a manchineel 'beach apple'", British Medical Journal, 2000, Aug 12, p. 428