Food Healthiness at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Food Healthiness at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

"Without question, equipping and preserving sufficient food and drink on long-distance voyages was intimately tied with the survival of the crew in terms of morale and nutrition and, ultimately, could determine the success or failure of the voyage." (Cheryl A. Fury, "Health and Health Care at Sea", The Social History of English Seamen, 1485-1649, p. 198)

Pirate Edward Low's Men Dining, From

Historie der Engelsche Zee-Rovers (1725)

Food is a topic of monumental importance to all those who made voyages of any significant duration. It had a direct impact on the health and well-being of a crew and was considered a crucial part of those healing from wounds and surgeries during the golden age of piracy.

There is a wealth of information about some of the elements of feeding sailors during this period, particularly what they ate and how they got it. The wealth of information on food eaten by sailors exists partially because the navy was involved with the kinds and procurement of food on long voyages and they kept good records. In addition, as sailors expanded the map, they also expanded their diet with some of them taking notes on what they consumed. However, actual preparation and eating of food were apparently considered so mundane that seamen barely mention them in their accounts. Nor are period cookbooks necessarily a reliable guide to food preparation and consumption by sailors since they were written primarily for the upper classes in England. As nautical food researcher Grace Tsai notes, "Cookbooks were often made by and for the elite, because most people couldn’t even read and write.”1 There is some educated discussion about how many sailors were able to read or write (the two skills were taught separately)2, but the recipes found in a cookbook belie their usefulness at sea, where fresh foods were rarely available on ships making long voyages.

Artist: Thomas Luny - East Indiaman Hindostan, (1792)

This is the first of a series of articles which look at food as used by English sailors during the golden age of piracy (1690-1725), broadly dividing them into navy sailors, merchants, privateers and select buccaneers, sailors and pirates. This first article examines how the body was believed to use food and looks at the how the healthiness of food provided to sailors was perceived. The second article discusses the many ways sailors obtained food while traveling. The third article is a continuation of ideas about obtaining food while under sail, focusing on several formal and informal 'provisioning stations' which were used by sailors. The fourth article looks at victualling and the types of food consumed by the navy, navy officers, merchants, privateers and pirates. The people and procedures common to all sailors during this period are discussed in the fifth article including an examination of how food was handled, cooked and eaten shipboard.

1 Tyler Allen, "Dining on the high seas", Spirit Magazine, Texas A&M Foundation Website, gathered 9/4/19; 2 See Ed Fox, Piratical Schemes and Contracts, Thesis, 2013, pp. 90-101

Thories on How the Body Used Food in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries

"Wherefore it appears to me necessary to every physician to be skilled in nature, and strive to know, if he would wish to perform his duties, what man is in relation

Hippocrates

to the articles of food and drink, and to his other occupations, and what are the effects of each of them to every one." (Hippocrates, "On Ancient Medicine," The Genuine Works of Hippocrates, Translated by Francis Adams, 1849, p. 175)

To understand food from the perspective of doctors during this time, it is important to be able to appreciate how they thought the body processed food. Like nearly all of medical understanding during this period, the way the body used food was understood through the lens of humor theory. (While new theories began to replace some of the ancient humoral concepts in the late 17th century1, their adoption had not yet occurred by the end of the golden age of piracy. Change occurred very slowly in medicine.)

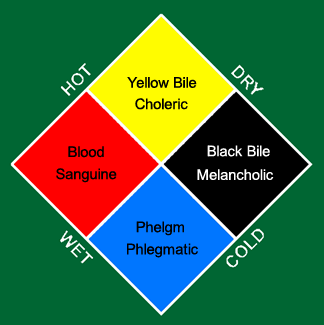

The concept of how food was processed by the body was fairly simple on the surface. As modern medical anthropologist Byron Good notes, "nearly all normal and abnormal physiological processes ...were understood in relation to the observed transformative powers of heat."2 In basic terms, food was thought during this time to be 'cooked' by the body in various organs including the stomach, liver and heart, among others. The bodily humors - represented by the four fluids blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile - were the result of this cooking.

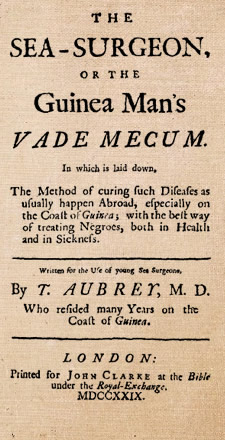

Eighteenth century ship's physician Thomas Aubrey, ostensibly writing 'for the Use of young Sea Surgeons', explained the process of converting food into humors:

The Title Page of Aubrey's Book

whatsoever we eat, or drink, being conveyed thro’ the Æsophagus into the Stomach, is there, by the natural Heat, together with other natural Properties co-operating with it very aptly digested, or concocted ['cooked'], which is only a Separation of the most subtile, from the most gross Parts of the said Aliments [food]; and the most gross Particles being unapt to be received by the lacteal [lymph] Vessels, partly by their proper Ponderosity [weight], and partly by the Motion of the yielding Intestines (being [that these particles are] no more useful to Nature) do glide down by Degrees towards the Rectum, and so are discharged. But the most subtile, pure, delicate Part [of the food], commonly denominated Chyle, creeping up and down the Folds of the Guts, is more and more rarified [purified], and becomes more and more perfect [by being heated].3

Aubrey goes on to explain:

our Blood is generated from those Aliments, and not only the Blood, but the Spirits, and all other Humours existing in the Body; existing (I say) because of whatsoever kind the Humour be, it is nourished, sustained, and hath its various Motions, Functions, and Faculties, from the aerial ingenous Spirit existing in its Pores; which Spirit comes partly from the Air by Inspiration [breathing], partly from the Chyle, and partly from the sanguinary Mass [the blood in the body] …and differ not from the Blood, because they cherish and sustain one the other...4

While the language makes this sound confusing, it essentially follows the simple explanation given previously. As the proto-humor chyle is heated and processed by the stomach and intestines, it is purified and converted into the finer humors such as blood, the biles and phlegm, while the parts of food that cannot be converted are excreted.

A key to digestion as it was understood at this time is understanding the concept of chyle. Byron Good explains, "The stomach sorts out the indigestible material and transforms the raw food into 'chyle,'

Photo: US Government

Chyle (Lymph & Fatty Acids)

'a fluid or humor, preconcocted [preheated] and already elaborated [broken down], but still needing its concoction to be completed' (Galen, Usefulness. I: 205)."5 Another author explains that chyle is "a milky fluid, sometimes called 'juice' in English treatises."6 The chyle would then make its way to the liver where it was converted into blood and then sent throughout the body.

One part of the blood travels to the heart, where it undergoes further cooking and is combined with the breath, thus being transformed into the 'vital breath.' This vital breath or pneuma travels through the arteries to each part of the body, where it interacts with the blood and 'true assimilation' occurs, nourishing the organs (Ibn Sina, Canon: 113). The liver thus produces the 'dense part' of the humors, the heart the 'rarefied part,' and the breath produces life.7

This explains how food becomes blood and pneuma from the ancient perspective, which was still in use during the golden age of piracy. Drawing from Galen's comparison of food concoction to fermenting wine, Good says, "[Yellow] Bile is produced as a hot, light (dry) by-product which rises to the top as 'foam' on the cooking blood or as the foamy 'flower' on the fermenting wine. Black bile, the atrabilious [melancholy] humor, is the cold, heavy (moist) by-product, compared to the sediment or dregs, the earthy residue of fermentation."8

The Four Humors, Temperaments and Associated Temperatures

Avicenna (c. 980 - 1137) similarly explains in his book The Cannon of Medicine, "One must not forget that the most fundamental agents in the formation of the humours are heat and cold. When the heat is equable [even], blood forms; when heat is in excess, bilious humour [yellow bile] forms; when in great excess, so that oxidation occurs, atrabilious humour [black bile] forms. When the cold is equable, serous humour [phlegm] forms; when cold is in excess so that congelation [congealing] becomes dominant, atrabilious humour forms."9

This shows how each of the four bodily humors were thought to be created from food. Good goes on to state, "Feces are produced from the concocting in the stomach; excess black and yellow bile are discarded from the cooking in the liver; urine from digestion in the liver and the nutrition of the kidneys. And all other exuda - perspiration, ear wax, saliva and mucus, eye sordes, nails, and hair - are produced in the final stage of transformation of aliment into living tissue."10

The concept of humor creation was complicated by the idea that people were thought to fall into categories called temperaments. Each person's temperament was based on the dominant humor in their body. This temperament was further associated with the persons 'temperature' (See the chart above left.) Medical historian Andrew Wear explains this belief:

Food ...intimately shaped a person, for, although each one was born with a specific humoral constitution, particular foods and the way they were digested produced chyle and blood which could be suitable for or analogous in quality (hot, cold, moist, dry) to it or hostile to it. If the latter was the case, a disordered constitution resulted, which was out of balance either because one or more humours predominated, or because a humour became abnormal and pathological through being burnt or putrefied. [This could occur when the organs overheated the chyle, particularly the liver.] The English regimens followed the Galenic tradition in emphasising the connection between food and the body.11

These 'specific humoral constitutions' or temperaments manifested themselves in a patient's body type which can be seen in the image below left. Since foods created the bodily humors, certain foods and diets thought to produce more of the types of humors and digestion most needed by people of each temperament. Although not a physician (or even a medical professional), contemporary author Thomas Tryon provided insight into this link between a person's temperament and their diet.

, Physiognomische Fragmente, Johann Kaspar Lavater, 1775-8m.jpg)

The Four Body Types By Temperament, From Physiognomische

Fragmente,

By Johann Kaspar Lavater (1775-8)

Tryon warned that phlegmatic temperament was of a cold nature, requiring temperance and discretion in diet. "Meats and Drinks good for this Complexion are all sorts of drying warming things, as Bread eaten with Oyl, let Butter be eaten sparingly, Cheese is good, not new, but old, also, all Gruels and Pottage [thick stews or soups]...

thin, brisk and lively, for such things are easie to be concocted, and quick on the Stomach; likewise all spicy Herbs... but Flesh they ought to eat

sparingly"12. He noted that they should drink beer in preference to ale or wine mixed with water.

He said that those of a choleric temperament "ought to be Sober, and accustom themselves to be mean [moderate] in all things. as Meats, Drinks, Exercises, and especially in Communication... All sorts of Food and Drinks, that are rather inclined to Coolness than Heat, are most profitable to People of this Complexion; and as in quality, so also ought they to be careful that they do not extend in quantity"13.

Tryon felt those of a sanguine temperament should eat "things of a simple Nature, wherein Bread hath the first place; Milk and various Dishes made thereof, sundry sorts of Herbs in their seasons, being well and naturally prepar'd; also Gruels and Pottage made of Oatmeal, being made thin, and quick boyled... cleansing and opening the Passages, they beget Appetite and help

Concoction... [along with] Flesh and Fish that have a clean Nature [and] easy Concoction"14. He goes on to suggest "Bread, Butter, Cheese, and all sorts of Food made of Flour and dried Fruits, are a strong healthy Diet."15

Artist: Robert White - Thomas Tryon (1703)

He felt those of a melancholic temperament were generally more slow and dull than the other temperaments and should become more free and spirituous though the use of 'Strong Beer, Ale, Wine, or any spirituous Drinks', although he also waffles a bit on this point, later recommending they be used sparingly.16 Tryon then loses his focus, wandering off topic before suggesting what types of food would be best-suited to those of a melancholy complexion.

Diet and temperament were also important to those who were healing. Contemporary military and naval surgeon Richard Wiseman states that "no man of common sense but knows, that as a full Diet is hurtful for those of a Plethorick [sanguine] Body, in Wounds where there is great Inflammation and the like Symptoms; so when a Body hath been exhausted through loss of bloud or the like, it’s reason that a greater liberty should be allowed, as to take Broths, Jellies, new-laid Eggs, &c."17Wiseman is pointing out here that the 'full' diet containing broth, jelly and such would be inappropriate to people of a sanguine temperament because they already make an excess of blood, which agrees with Tryon's assessment. However, such foods would be appropriate to them after a loss of blood because it would cause them produce more blood.

When discussing patients with healing wounds, French surgeon Ambroise Pare gives some insight into what is best for patients with different temperaments when they were healing. He says that patients who are "plethorick [phlegmatic - cold and wet]; he shall abstaine from salt and spiced flesh, and also from wine; If he shall be of a Cholerick [hot and dry] or Sanguine [hot and wet] nature: In steed of wine he shall use the decoction of Barly or Liquerice [licorice], or Water and Sugar..."18 Once again, the melancholic [cold and dry] temperament is overlooked.

Not everyone prescribed to the humor-temperament-diet connection. Naval physician William Cockburn seemed more concerned with the amount of activity an individual engaged in as being more relevant to their diet than the humoral characteristics. Of sailors, he said that

the bodies of such working people, not only make the best of such solid food [as was provided by the navy, speaking specifically elsewhere to ship's biscuit, peas and oatmeal]; but this, ev'n, seems necessary for those who are oblig'd to undergo so great labour... in one part of their business or another, [so that] scarce one muscle of the whole body being left unimploy'd, their digestion and nutrition not only go as well on with them in this diet, as the most delicate food with Ladies; but this sort of victuals is, even, necessary for their toyl and labour, and that which is finer and more easily digested, would not prove of long enough continuance for their work.19

Artist: Phillipe Jacques de Loutherbourg

Sailors Working on the Dock (mid 18th c.)

Cockburn could have been writing today; many modern authors suggest that the sailor's diet was appropriate to their trade. Writing about Dutch sailors during this era, neurosurgeon Jacquez Charl de Villiers states, "The sailor’s work was physically demanding and called for adequate nutritional intake. The foodstuffs supplied were unrefined and the meals unattractive, but meals were adequate in bulk and nutritious within the restrictions imposed by the lack of effective methods of food preservation for a journey of unpredictable duration and under widely variable climactic conditions."20 Historian Christian Buchet says that the navy sailor's "menu provided a daily quota of 4,000 to 4,500 calories. ...the rations of naval crews were more than sufficient and indeed superior to the diet of an ordinary land-dweller."21

Ship's surgeons who wrote about medicine during this period do not have a lot to say about how the body used food, most likely because the theory of medicine was the considered the realm of the physicians. Surgeons were more concerned with the practical aspects of health. However, many of them had a rudimentary understanding of this because it was necessary to their trade. As a result, the diets which were appropriate to people healing from particular wounds and illnesses are often mentioned in their books. Although these recommendations are beyond the scope of this article, they can be found in the articles on particular health problems including: amputation, burns, drowning, fluxes [diarrhea and dysentery], foreign object wounds, fractures, gangrene, head surgery, simple wounds and venereal disease cures by salivation and sweating.

1 Emily Cockayne explains, "Contemporary assertions about the propriety of diets according to status started to replace Galenic humoural views, which prescribed different diets to melancholic and sanguine people, adjusted for age (both the very old and very young were though to benefit from a pappy diet). Such ancient views were still evident in the seventeenth-century works of authors such as Thomas Cogan, and to some extent Thomas Tryon." See Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, 2007, p. 87; 2 Byron J. Good, Medicine, rationality and experience, 1994, p. 103; 3 Thomas Aubrey The Sea-Surgeon or the Guinea Man’s Vadé Mecum. 1729, p. 3-4; 4 Aubrey, p. 8-9; 5 Good, p. 105; 6 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 49; 7 Good, p. 103-5; 8,9 Good, p. 105; 10 Good, p. 106; 11 Wear, p. 172; 12 Thomas Tryon, The Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness, 1697, p. 18; 13 Tryon, p. 14; 14 Tryon, p. 21; 15 Tryon, p. 22; 16 Tryon, p. 24-5; 17 Richard Wiseman, Several Chirurgical Treatises, 2nd ed., 1686, p. 346; 18 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 255; 19 William Cockburn, An account of the nature, causes, symptoms, and cure of the distempers that are incident to seafaring people, 1696, p. 7-8; 20 J.C. de Villiars, "The Dutch East India Company, scurvy, and the victualling station at the Cape", The South African Medical Journal, Feb. 2006, p. 106; 21 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Society in the Seven Years War, 2013, Translated Anita Higge and Michael Duffy, p. 44