Food Healthiness at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Food Healthiness at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Healthiness of the Sailor's Diet

"...it requires more than ordinary Care in supplying the Fleet with good and wholsome Provisions, the Want whereof subjects the Men to so many Distempers. This Care ought to extend it self as well to Quantity as Quality; for as nothing does more discourage a Sailor than his being wrong'd in the First, so is there not any thing subjects them to Diseases so much as a Defect in the Latter." (Sieur Guillet, 'Victualling', The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated)

Most, if not all, English sailors were at some time in their career exposed to

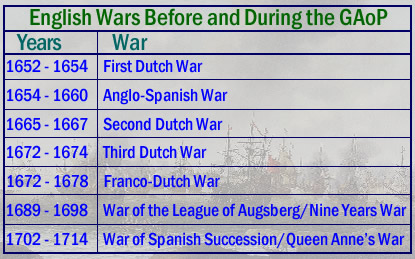

English Wars During the GAoP

Image Artist: Pieter Cornelisz van Soest - Attack on Medway (c. 1667)

the menu of the British Navy. This is because England was involved in a variety of wars leading up to and during the golden age of piracy when the sailors active during the GAoP would have been learning their trade. (See the chart at right.) The English navy's need for sailors during wartime led to the merchant sailors being press-ganged into the fleet. Even the majority of pirates would also have started their careers either in the navy or merchant marine service. As a result, most sailors would also have been exposed to the naval diet during their career.

For English sailors, the naval diet included salt beef, salt pork, dried or salted fish, ship's biscuit (bread baked and further dried1), reconstituted dried peas, oatmeal or oatmeal porridge (burgoo), cheese and butter.2 (The details of this diet are discussed in detail in the article on sailor's foods.) The Dutch Navy's diet was similar although Nathaniel Boteler noted in the mid-17th century that the French and Dutch "content themselves with a far less portion of flesh and fish than we do, and instead thereof do make up their meals with peas, beans, wheat, butter, cheese, and those white meats as they are called."3 (Note that the word 'meat' could be used during this period to refer to "food in general"4 as it is here.)

Of this diet, adroit commentator Boteler suggested "our common seamen are so besotted in their beef and pork that they had rather adventure on all the calentures [fevers] and scurvies in the world [caused by poor provisioning] than to be weaned from their customary diet, or lose the least bit of it."5

Photo: Nick Saum - Hominy with Coins for Scale

Butler suggested that the English would be better off following the diet of the French and Dutch, or that of the Italians and Spanish who "live most upon rice, oatmeal, biscuits, figs, olives, oil and the like"6. He stated that, "by this diet [these other sailors] live far more healthily at sea than we do, or but [by the diet] of our own Colonies at St. Christophers, the Barbadoes, Virginia, and the Bermudas, who for the most part live and thrive well with these husked de-hominie [hominy - dried corn]"7. He also suggested the use of "various kinds of peas, which are everywhere found in the West Indies", cassava flour, "pompians [pumpkins], potatoes, plantains, oranges, lemons, limes [and] pines" which he considered "very nourishing and healthful" given "that the Dutch men-of-war, which yearly haunt all those coasts, do continually maintain themselves with victual and health with these provisions for many months and years together"8.

While ships did make use of local foods, including nearly all of the things he mentioned, Butler's suggestions were never officially adopted. However, alterations to the naval diet were sanctioned for ships in foreign climes. As early as 1678, substitutions to the standard naval diet were allowed by ships travelling south of the 39th degree North parallel (primarily referring to ships sailing in the Mediterranean),

Duff Pudding Bag on Plate, Painted on a Tile

including rusk [locally-baked biscuit9] instead of naval biscuit, flour and raisins, currants or suet (to be made into 'duff' or 'pudding' by boiling or steaming them together in a bag) in place of beef or pork with peas, rice or stock fish rather than cheese and olive oil in place of butter.10

By current standards, these substitutions are considered healthier than the standard navy diet. However, they were "no more popular with the seamen than was the 'beverage' (country wine mixed with water) instead of beer. What they really preferred was pork and pease. They complained they had not time to make duff [pudding]; and they were not impressed by the argument that meat might go bad or was unsuitable in hot climates."11

Of course, local food wasn't always seen as a better alternative. Naval surgeon John Moyle suggested that such diets could cause health problems. He explained, "when our English victualling [the standard navy diet] is done, and we change to some other Country victuals, I have known Fluxes [diarrheas and dysenteries] come all these ways."12 In that passage, Moyle also mentions local water as a possible culprit, which is probably to a large degree the more likely culprit in cases of diarrheas.

Nathaniel Butler also says that "feeding them [navy sailors] on salt meat with only the diet of the ship, two or three months sometimes, before their going out to sea, must needs prostitute them to much sickness and infection; and I believe hath been one main occasion of those so extraordinary losses of men, that have lately been found in our sea expeditions."13

Photo: Isaac Sailmaker - Ships at Anchor in the Thames (late 17th/early 18th Century)

This occurred because ships were sometimes left waiting in a harbor for long periods of time before they were allowed to leave. While waiting, those aboard had to stay there and eat sea rations (referred to as 'petty warrant victualling'). By 1701, the petty warrant diet required that sailors in the harbor be given fresh beef in place of salt beef two days a week and fresh bread in place of biscuit.14 However, it is Butler's suggestion that an extended diet of salt meat caused illness that is of interest here. (The healthiness of salt victuals is discussed in detail in the next section.)

Not everyone looked askance at the diet supplied to English Navy sailors; some naval officers felt it was quite healthy. When commenting on the victualling agent who provided food to the English Navy at Lisbon, Portugal in 1706, Admiral Sir Cloudsley Shovel reported that the food there was "a great preservative and much contributed to the health of our seamen"15. In 1703, the Victualling Commissioners said that "the allowance of oatmeal and pease for five of the seven days (which are in themselves taken to be cleansing and healthful)... and the quality of the provisions supplied them [the navy sailors] abroad, as wine, oil, rice, etc.; it is, in our humble opinion, a very good and wholesome state of victualling."16 Of course, it was in their best interest to say as much.

Artist: Joseph Nicholls

Queen Annes Revenge, From General History of the Pirates (1736)

Before leaving this section, it is worth mentioning the diet that was likely found on English merchant ships. As already mentioned, many of the merchant sailors would have at one time been conscripted into the English Navy during the various wars. As a result, they would have been familiar with the naval diet. One of the largest merchant ships concerns during this period was the East India Company, an organization run along lines similar in many ways to the English Navy. While their standing orders of 1621 do not spell out the whole of their merchant sailors' diet, they do mention the use of beef and pork in casks, which clearly refers to salt meats like those in use by the navy.17 While smaller merchant ships were free to take whatever food they desired for sustenance while sailing, most ships setting out from England on long trips likely carried provisions similar to those specified for the English Navy and East India Company. Nearly everyone aboard would have been familiar with this diet, it kept fairly well for the first several months and most sailors were comfortable with it.

Like the merchant sailors, the majority of English pirates would have came through the same system, being similarly familiar and comfortable with the type of food provided by the navy. This is not to say that pirates never ate anything else (for there is some evidence to the contrary as we shall see), however they were as likely to take navy type victuals from captured merchant ships as they were other provisions.18

1 Like many words during this period, 'biscuit' is an imprecise term. Thomas Dryche and William Pardon defined biscuit (as well as the words 'biket' and 'bisquet') in two very different ways in their 1735 New general English dictionary: "Commonly understood of small Cakes made by the Confectioners, of fine Flower [flour], Eggs, Sugar, &c. also the Bread carried to do, is called Sea-Bicuit." The idea of 'Sea-biscuit' is expanded in Samuel Johnson's dictionary of the English language (1768 edition): "A kind of hard, dry bread, made to be carried to sea". Neither of these definitions mention what biscuit was made of or how it was prepared. Johnson cites Richard Knolles 1603 account The Generall Historie of the Turkes as the source of his definition. Knolles repeatedly mentions that 'biskit' was carried in Spanish vessels at that time (see pages 660, 719, 898 and 899). Of more interest to this discussion, Knolles reported that when the Turkish army ran out of food, "they were enforced to give their camels bisket and rice, and when that failed, they gave them their pack-saddles to eat, and after that pieces of wood beaten into pouder, and at the last the very earth" (p. 996). Knolles makes the lack of moisture found in ship's biscuit fairly clear by pairing it with rice, which at least suggests that this was the twice (or even three or more times) baked bread that the Americans started referring to as 'hardtack' in the nineteenth century. (See the origins of hardtack on Etymology online). 2 See Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 254-5; 3 Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, p. 66; 4 Samuel Johnson, "Meat", A Dictionary of the English Language, 3rd ed., 1768, not paginated; 5,6 Boteler, p. 65; 7,8 Boteler, p. 66; 9 As with 'biscuit' (see footnote 1), 'rusk' seems an impricise term. In 1699, Dampier defined 'fine rusk' as "Bread of fine Wheat-Flower, baked like Bisket [twice-baked], but not so hard". (Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 303). Since he prefaces this as 'fine' rusk, it would seem regular (none-fine) rusk was just locally-obtained twice-baked bread. Samuel Johnson's dictionary of the English language (1768 edition) defines rusk as: "Hard bread for stores." which sounds like the same thing as biscuit. So it seems most likely that rusk was being used here to differentiate it from English biscuit, instead being locally made. 10 J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 167; 11 Merriman, p. 250; 12 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 100; 13 Boteler, p. 43; 14 Merriman, p. 255; 15 Cited in Merriman, "24. Admiral Sir Cloudsley Shovel to Victualling Board From on board the Association in the Bay of Wares [Oiras, at the mouth of the Tagus], 27th December 1706", p. 279; 16 Cited in Merriman, p. 270; 17 East India Company, The lawes or standing orders of the East India Company, 1621, p. 35; 18 See for example Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 215, Daily Post, 7-25-21, Issue 567 & Weekly Journal or British Gazetteer, 1-13-22

Healthiness of the Sailor's Diet: Salt

"It was Time to consider what they [William Mayes pirates aboard the Pearl] should do with themselves, their Stock of Sea Provision was almost spent, and tho’ there was Rice and Fish, and Fowl to be had ashore [on Madagascar], yet these would not keep for Sea, without being properly cured with Salt, which they had no Conveniency of doing; therefore, since they could not go a Cruising any more, it was Time to think of establishing themselves at Land..." (Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 57)

Salt was one of the few reliable preservatives during the golden age of pirates, resulting in meat and some other things such as butter being preserved in it for use at sea.

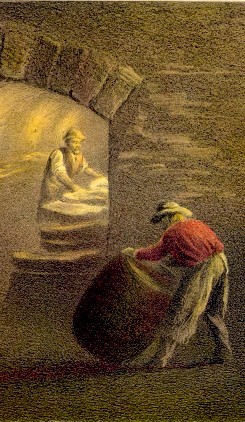

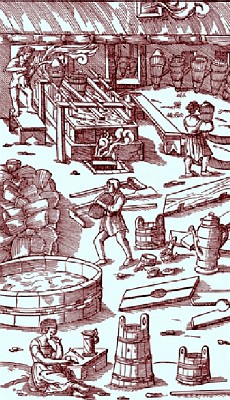

Pork Salting Operation in Cincinnati (1873)

Modern medical historian Zachary Friedenberg notes, "salted meat was the cornerstone of the seaman’s diet."1 Modern researcher Grace Tsai, the scientist who started the Ship Biscuit and Salted Beef experiments at Texas A&M university to learn more about the foods used at sea during the 17th century did so because the naval diet didn't make sense to her. She explains, "the sailors’ sodium intake was 42 times the upper limit per day, which should kill somebody. I eventually decided that the only way to further analyze this would be to actually make the food and put it on a ship to see how it degrades over time."2 Salt figured heavily in sailors diets during this time and its' impact on health as perceived by the doctors and sailors is of interest.

When salt meat was prepared by a ship's cook, it was not just taken out of the brine and cooked. As early as 1634, Nathaniel Boteler stated that the ship's "Cook is also to take especial care and heed that both the flesh and fish be timely and sufficiently watered, and shifted, for the more wholesome feeding of the ship’s company."3 'Shifted' does not just mean 'moved'. The Gentleman's Dictionary of 1705 explains that 'shifters' were "those Men on board a Man of War, who are Employ'd by the Cooks, to Shift or Change the Water in which the Fish or Flesh is put and laid for some time, in order to fit it [make it acceptable] for the Kettle."4 The shifters' job was to take the meat out of the brine and put it in fresh water to remove some of the salt. Even then, the meat was still salty. Barnaby Slush, a naval cook aboard HMS Lyme,complained of the "the intollerable Salt[i]ness of some of the Victuals ...notwithstanding all the Pains I take in Shifting, and thorow Boyling of it"5

Although Boteler says that sailors preferred salt meat, the taste for it may have declined over time. Modern historian Emily Cockayne states that "With improvements in agriculture, importation and transportation, the taste for salted food declined (as they could lead to mouth ulcers and extreme thirst), and they became regarded as of inferior quality, more fit for the poor and needy."6 Still, meat packed in brine was the best way to preserve it and it continued to be a staple of the sailor's diet long after then end of the golden age of piracy.

The medical view of salted meat was somewhat mixed. Thomas Tryon asserted that beef "ought not to be eaten until it be well season'd with Salt, or if eaten fresh there ought to be good store of Salt eaten with it, and boiled in plenty of Water, which will sweeten and cleanse it from its grossness"7. He goes on to say that "'tis with the pure Spirits that it [salt] delights to joyn it self and thereby preserves them from Evaporation, and consequently keeps the Meat sweet and sound and therefore Meat so salted

Making Brine (Used to Salt Meat), From De

Re

Metallica, By Georgius Agricola, 1556, p. 552

will eat much sweeter, and keep longer, and generate better Blood and Nourishment, and is easier of Concoction."8 Not everyone agreed with this. Boteler, as mentioned, felt that consumption of too much salt led "to much sickness and infection; and I believe hath been one main occasion of those so extraordinary losses of men, that have lately been found in our sea expeditions."9 Sea surgeon John Atkins said that meat on naval ships, "being half eat up as we call it, with Salt, in a few Months after landing there ['warm countries' such as those on the west coast of Africa and the West Indies], [gives] room to Complaints and Sickness."10

Salt meats were also believed to be one of the possible causes of scurvy. Boteler warned that "seething [boiling] of our meat in salt sea water causeth many sea diseases and especially the scorbute [scurvy]; and therefore is as much as may be to be avoided"11 In his book written for sea surgeons mates, East India Company surgeon John Woodall stated, "The cheefe cause [of scurvy] is the continuance of salt diet, either fish or flesh, as porke and the like which is not [able] to be avoyded at sea"12. (In fairness, Woodall lists a variety of other possible causes, but salt meats were the only one he identified as being 'cheefe'.) Navy physician William Cockburn said that scurvy "'tis a necessary consequence of an idle life, and of feeding on Salt Beef and Pork"13. This was as true for the merchant ships as it was for the navy. Merchant Sir William Hodges noted that "if there be not liberty of fresh Air and fresh Provisions, Experience shews the salt Seas and salt Victuals, in staying long in Ships, kills ten times more than the Sword…"14 While naval surgeon John Moyle didn't directly accuse salt meats of causing of scurvy, he did note in his first book on sea surgery that it could sometimes be caused "from over full dyet, of Flesh or Fish"15. With the prevention of scurvy in mind, naval Captain Townsend followed the example of hospital ship surgeon James Christie in the early 18th century, suggesting "that live sheep be carried in H.M. ships in order to supply patients with meat free from salt" to help prevent scurvy.16 The lack of knowledge on the true cause of scurvy allowed for such misunderstandings.

The sailors' views of the healthiness of salt meat was different from doctors of the time. Navy cook

Pork Salting and Stacking Operation in Cincinnati (1873)

Barnaby Slush explained that "the Sailors are everlastingly Railing against me [about the saltiness of the victuals]; and say, I am the Prime Occasion of scorching up their Intrails."17 Slush blamed the navy victualling agents, "who to preserve Meat, return'd home from Foreign Voyages, are engag'd to bury it in whole Cart Loads of Salt and then deliver it out, again to Ships' ev'n Bound to the West Indies"18. He felt that whatever meat wasn't used on a previous voyage was just repacked in brine to disguise the fact that it was old and likely to soon go bad. He likewise suggests that poorer quality meat was purchased and hidden by the excess of salt and brine.

Navy and merchant sailor Edward Barlow said that while he was sailing on the merchant vessel Experiment in 1670, "eating salt victuals, made us many times very dry, and we could have been glad many times of a drink of water if we could have told where to have got it, for it was scarce with us"19. (Fresh water was a precious commodity at sea during extended voyages.) Adventurer and privateer William Dampier said while traveling on the Cygnet in the East Indies 1691, "Our Food also was very bad; for the Ship had been out of England upon this Voyage above three Years; and the salt Provision brought from thence, and which we fed on, having been so long in Salt, was but ordinary [poor] Food for sickly Men to feed on."20

Privateer William Funnell explained that after being at sea for twenty days in 1705, their preferred fresh provisions were gone and they had to limit their rations to "half pound of Flower a Man per day, and our two ounces of Salt Beef or Pork every other day. The Meat has been so long in Salt, that when we boiled it, it commonly shrunk one half. So we finding a loss in boiling our Meat,

Photo: Ramesh Thadani - Salted and Dried Fish (Arapaima) in the Amazon

concluded to eat it raw; which we did all the Voyage after, so long as it lasted."21 (This would have done little to make the meat healthier; particularly if they didn't wash the salt off first.) Navy sailor Clement Downing agreed with Funnell. His ship HMS Salisbury had purchased pork at Bengal, India in 1722 and salted it, being "cut out according to the usual Form of the Navy; that is, two Pound[s] for three Men at short Allowance. But by the time they had been in Salt about two Months, you might have put a whole Piece in your Mouth at two Mouth-fuls. This occasioned a good deal of grumbling."22 With these provisions in mind, Downing later reveals that "the Pump was directly put in the Water-Cask, and every Man had as much Water as he could drink; which at that time was very refreshing, being in a hot Climate, and nothing but salt Provisions."23

These comments stand in stark contrast to Butler's assertion that "common seamen are so besotted in their beef and pork" that they would rather have it make them sick "than to be weaned from their customary diet, or lose the least bit of it."24 Of course, this is a rather small sample, taken from men who were able to write books about their experiences. It must also be remembered that people are much more likely to express complaints than they are to express satisfaction with things such as food.

1 Zachary B. Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail, 2002, p. 64; 2 Tyler Allen, "Dining on the high seas", Spirit Magazine, Texas A&M Foundation Website, gathered 9/4/19; 3 Nathaniel Boteler, Boteler's Dialogues, 1929, p. 15; 4 Sieur Guillet, "Shifters", The Gentleman's Dictionary, 1705, not paginated; 5 Barnaby Slush, The Navy Royal, Or a Sea Cook Turn'd Projector, 1709, p. 67; 6 Emily Cockayne, Hubbub: Filth, Noise, and Stench in England, 1600-1770, 2007, p. 95; 7,8 Thomas Tryon, The Way to Health, Long Life and Happiness, 1697, p. 58; 9 Boteler, p. 43; 10 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 356; 11 Boteler, p. 65; 12 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639, p. 179; 13 William Cockburn, An account of the nature, causes, symptoms, and cure of the distempers that are incident to seafaring people, 1696, p. 17; 14 William Hodges, Humble proposals for the relief, encouragement, security and happiness of the loyal, couragious seamen of England, 1695, p. 33-4; 15 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 96; 16 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 276; 17 Slush, p. 66; 18 Slush, p. 67; 19 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 182; 20 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 124; 21 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 225; 22 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 99; 23 Downing, p. 97; 24 Boteler, p. 65