Obtaining Food at Sea Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Obtaining Food at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Obtaining Food at Sea in the Late 17th and Early 18th Centuries - Buying vs Trading

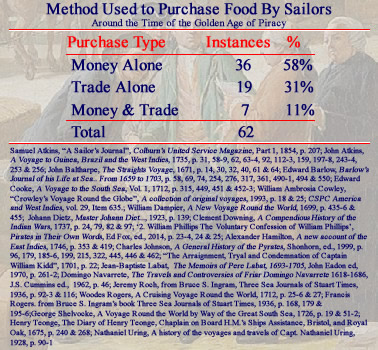

Method Used to Purchase Food Around the Golden Age of Piracy

Artist: Nicolas Bernard Lepicie - Courtyard of the Customs House (1775)

The information on ships purchasing food can also be broken down the way in which they paid for the provisions. This results in a smaller data set, however, because many of the citations do not clearly explain how provisions were purchased. Of the 106 instances of food being procured by sailors, only 62 of them make the method of purchase clear enough to be included in this discussion. The majority of these sailor's accounts mention people on ships purchasing food with money alone (36 accounts or 58% of the total). Accounts where trading alone was used to procure provisions makes up 31% of the data (19 accounts). The balance of 7 accounts (11% of the data) are where both trading and money were used to obtain food. Note that this discussion will exclude instances where pirates forced ships to take unwanted items in trade in order to make the theft appear legitimate since this was examined in detail in the previous section and it doesn't constitute a legitimate trade.

Buying and trading are seen by many today as pretty distinct methods of purchasing, although this was likely not not as significant during the golden age of piracy. Trading frequently occurred because the sailors were dealing with native populations who had little use for their currency. John Atkins explained that while he was at São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón in January of 1722,

Artist: Jan van Brosterhuyzen - Sao Tome Harbor (c. 1645)

they come to us in Way of bartering, very cheap, A good Hog for an old Cutlash; a fat Fowl for a Span of Brazil Tobacco, (no other Sort being valued) &c. But with Money you give eight Dollars [probably referring to a Dutch coin such as the Leeuwendaalder -Lion dollar/Zeeland- valued at 3 shillings1] per Head for Cattle; three Dollars for a Goat; six Dollars for a grown Hog; a Testune [a Portuguese coin worth about 1 silver and 3 pence2] and a half for a Fowl; a Dollar per Gallon for Rum; two Dollars a Roove for Sugar; and half a Dollar for a Dozen of Paraquets3

From Atkins' tone it is pretty clear that trading here was cheaper than using cash at out-of-the-way locations. It should not be surprising that currency would be primarily of use in large commerce centers. As Atkins elsewhere explains, "Coin is the dearest way of buying, at distance from Europe."4 This is verified by Woodes Rogers in his account of the privateer voyage of the Duke and Dutchess when they stopped in the Cape Verde Islands in 1708. Rogers comments, "The People at all these Islands rather chuse Clothing or Necessaries of any sort than Mony, in return for what they sell."5

1 Francis Turner, 'Money and Exchange Rates in 1632', 1632.org & John Kersey, 'Dollar', Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, 1708, not paginated; 2 John Kersey, 'Testoon', Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, 1708, not paginated; 3 John Atkins, A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 179; 4 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 112; 5 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 26

Purchasing Food with Money

The concept of a purchase price is complicated because it is difficult to translate the value of money at this time into something which would make sense today. In addition, the relative value and scarcity of an item in one location as compared another further complicates understanding the value of money at this time. While these things are still true to some degree today, they would have been more pronounced during this period when communication

between remote locations took so much longer. If that weren't enough, there was an unusual mix of currencies available in sea-side locations subject to a lot of ship traffic. The exchange rates between the various currencies would also have varied to some degree from place to place as well as from one time period to another, although England made attempts (which were often ignored in remote colonies) to standardize exchange rates.

Several of the instances where cash was used to purchase provisions present the prices in terms of English currency. Not surprisingly, it was used it England. As mentioned previously, Navy chaplain Henry Teonge says that when HMS Bristol was at Dogger bank in June of 1678, "we found two boats fishing, and bought of them ling and fresh cod of four foot in length for 6d. [pence] apiece; bret and turbot for 2d. apiece: cheap enough."1

Ports in neighboring Ireland apparently had no problem with English currency. Edward Barlow said that when the East Indiaman Wentworth sailed into Kinsale, Ireland, 'good provisions were very cheap' and he was able to purchase "good salt butter for three halfpence per pound, and fresh butter for twopence, and good beef for four shillings the hundred[-weight], and good mutton for a penny the pound... pork for a penny the pound, six or seven eggs a penny... [and] fresh cod for twopence and threepence."2 When there the next year, Francis Rogers after deboarding the Arabia, he purchased "a fine large salmon for 8d. or 9d., ...beef [for] 5 farth[ings - 1/4 of a pence]; and 1 1/2d. and the mutton 9d. and 10d. a quarter, and eggs, as our landlady told us at that time, extravagant dear, being but 9 for a penny"3. (Despite the landlady's dismay at the prices, they were cheaper than when Barlow was there the year before. Rogers said "we thought ourselves in the land of plenty, and, just come off a long tedious, starving, drink water voyage, we did not a little indulge ourselves."4)

Even far from home, English currency could be useful, such at English outposts, although England had a tendency not to supply a sufficient amount of currency to their colonies.5

Cartographer: Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d' Anville

Map and Image of Cape [des] Palmas, Africa, From Gvinea propria (1743)

The local English 'factory' or trading station at Sesthos [modern Cape Palmas, Liberia] clearly dealt in English currency, since John Atkins, who was quite fastidious about reporting the costs in local currency when it was relevant, says that slave ships there were able to purchase rice "at about 2s. [silver] per Quintal [hundredweight]."6 This should not be entirely surprising because the English factories were part of the triangle trade. Ships sailed from England to the African coast with money, alcohol and goods of interest to the African slave traders, purchasing slaves and provisions at he factories there, and then sailed to the West Indies or English Colonies to sell the slaves for sugar, rum and other produce. They then took this back to England to sell it. Their currency would have sailed with them.

Other locations also appear to have accepted English money to some degree. Nathaniel Uring reported that when the the Joseph Galley was at Santiago in the Portuguese-held Cape Verde Islands in 1710, "we bought a large Hog for Two Shillings and Six-pence, and Goats at the same Rate; large Fowls for less than Six-pence a-piece; Oranges and Limes, Bannanoes and Plantans, cost us little or nothing."7

Artist: Olfert Dapper - City of Algiers, Algeria, From

Description de l'Afrique (1686)

In Algiers, Edward Barlow reported that when HMS Augustine was in port, he found he could "buy a hundredweight of good figs for six shillings halfpenny English money."8 At Hoogly, India on the country ship Recovery in 1683, Barlow said that a sailor could purchase "fowls, as hens and cocks, sometimes for the value of a penny a piece."9 (Note that he indicates value here, so it is possible he was using local currency and equating it to English currency.) Visiting Myanmar some time, sailor Alexander Hamilton advised that "wild Deer are so plentiful that I have bought one for three or four Pence; they are very Fleshy, but not Fat about them."10

One of the more extensive lists of provisions purchased with English money comes from John Atkins discussion of HMS Weymouth's visit to Pernambuco, Brazil in July, 1722 which is found in Charles Johnson's General History of the Pyrates. Atkins reports that "The Market is stocked well enough, at five Farthings per l., a Sheep or Goat at nine Shillings, a Turkey four Shillings, and Fowls two Shillings, the largest I ever saw, and may be procured much cheaper, by hiring a Man to fetch them out of the Country."11 It is interesting that English money could be used in a Portuguese port; one can't help but wonder if Atkins wasn't just converting Spanish dollars ('pieces of eight') or Portuguese cruzados to pounds.

Foreign currency was widely used outside of England and there are a variety of examples where sailors purchased victuals with such. There was a notable lack of British currency in the West Indies during this period because Britain believed that their colonies should produce raw materials rather than use from England.

Spanish Piece of Eight, 17th or 18th Century

Toward this end parliament enacted laws prohibiting the export of British silver coinage as it was felt the colonies should be providing Britain with precious metals rather than draining them away... This problem was critical as it adversely affected local commerce and forced the colonists to turn to foreign coins, primarily Spanish American silver produced in Mexico and Peru. The most widely used coin in the colonies was the eight reales (piece of eight), primarily clipped underweight examples that had made their way north from Mexico through the Bahamas.12

Within the colonies in the West Indies, bartering was often employed. However, British exporters bringing desired British goods into the colonies wanted silver over bartered goods. As a result, there was a shortage of silver.

[I]n colonial America most silver coinage in circulation came from Spanish America, Spain, the Netherlands, the German States, France and other foreign countries. Colonists were able to use these coins within their monetary system of pounds, shillings and pence because Britain set exchange rates between sterling and many foreign coins.13

Even, so the exchange rate fluctuated over time as well as between different colonies.

As suggested, one of the more popular currencies mentioned in the period and near-period sailor's accounts was Spanish currency, particularly dollars or pieces of eight. When Privateer George Shelvocke's ship Speedwell was at Santa Caterina Island in Brazil in 1719, he said, "I purchas'd 21 head of black cattle, some at 4 dollars [most likely Spanish Pieces of Eight], and others at 8; several hogs at 4 dollars each, and 200 large salted drumfish, at 10 dollars per hundred... [and] calavances [hyacinth beans], some of which I purchas'd with money, at the rate of a dollar per bushel, and some with salt."14 John Atkins reported that when he was in Jamaica in 1722 that turtle "sold at a Bitt [1/8 of a Piece of Eight] a Pound, like other flesh"15. Spanish currency was also found in the East Indies. Sailor Alexander Hamilton said that while he was in Rembang, Java, "I bought a Cow, fleshy and fat, for two Pieces of Eight, that weighed above 300 Weight"16.

Silver Rupee from the Reign of Aurangzeb (1659-1707)

When Edward Barlow was at Surat in 1697 aboard the East Indiaman Scepter, he said that for "cows we paid twenty-seven shillings the piece, or twelve rupees; and hogs about four rupees the piece, they being dearer at Bombay than at many other places in India"17. While it is not surprising that Barlow gave the price of cows and hogs in the local currency (rupees), it is interesting that he also reported the price of cows in English currency. It is not clear whether he was providing the exchange rate here or whether they had bought some cows in shillings and others in rupees. Since the English established their first Indian factory here in 1612, it is possible that the Scepter bought cows from them in shillings. Barlow's was a personal journal which was not published until it was discovered in the 1930s, so there doesn't seem much point in his giving the exchange rate.

Silver Akce from the Reign of Ahmed III, Ottoman Empire (1703-30)

In his book about the travels of HMS Weymouth and Swallow, John Atkins provides insight into non-English currencies used in African ports in 1721 and 1722. At Cape Corso Castle (in what is today Ghana) in November of 1721, Atkins said, "A lean Goat you may get by chance for five Accys [probably referring to an Akche or Akce - a silver coin of the Ottoman Empire]; a Muscovy Duck, a Parrot, or couple of Chickens for one."18 Sailing along the coast of Africa in 1721-2 between Whydah [Ouidah] and Cape Corso [Ghana], Atkins explained that provisions were readily available, but not cheap:

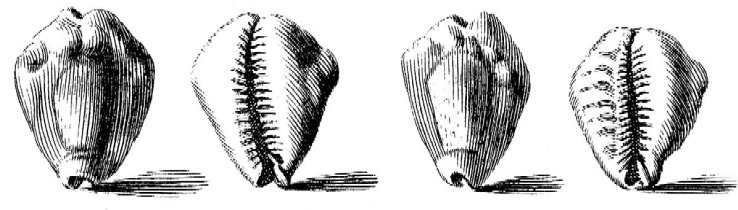

[ a 300 pound cow] will sell for two grand Quibesses; a Calf of 80 lib. weight for one grand quibess; a Sheep of 22 lib. for eight Gallinas; Fowls, five for a Crown; a Dozen Wild-fowl, or a Hog, for the same Money: but it's convenient on this Voyage always to provide Cowrys or Booges (little Indian Shells, called in England Blackamoors Teeth, bought at 1 s. and sold here at 2 s. 6 d. per lib.) as the readiest for this sort of Traffick.19

He goes on to explain that 200 cowry shells equalled a Gallina and 20 Gallinas equalled a grand Quibess (or 25 shillings). Cowry shells appear to have been a popular currency among the natives on the coast of Africa.

Artist: Niccolo Gualtieri - Cowry shells (Cypraea moneta), From Index Testarum Conchyliorum (1742) |

Sometimes the currency used is not clear form the text. In July of 1702, Francis Rogers was aboard the merchant vessel Arabia when she arrived at Aden in what is today Yemen. He explained that food there would have been cheap except that cattle had to be brought a long distance to reach the shore. As a result, buyers "used to give about 5 or 6 Arafs for a good likely goat and 7 or 8 for a sheep, and other provisions accordingly."20 What an Araf is isn't clear, although it seems likely it was some sort of Arabic coin.

1 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 240; 2 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, p. 550; 3 Francis Rogers, Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 195; 4 Rogers, p. 195-6; 5 'Money in Colonial Times', www.philadelphiafed.org, gathered 11/15/19; 6 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 62; 7 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 91; 8 Barlow, p. 58; 9 Barlow, p. 361; 10 Alexander Hamilton, British sea-captain Alexander Hamilton's A new account of the East Indies, 17th-18th century, 2002, p. 353; 11 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 199; 12,13 Louis Jordan, "The Comparative Value of Money between Britain and the Colonies", coins.nd.edu, gathered 11/16/19; 14 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 51-2; 15 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 243-4; 16 Hamilton p. 419; 17 Barlow, p. 494; 18 Atkins, Voyage to Guinea..., p. 92; 19 Atkins, Voyage to Guinea..., p. 112; 20 Francis Rogers. Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 168