Torso Wound Care Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Next>>

Torso Wound Care During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 6

Replacing the Omentum

It was widely agreed that the viscera (including the omentum and internal organs) could be restored to its place if it were done quickly.

Pushing in Guts, From Johannes Scultetus,

l'Arcenal de Chirurgie (1665)

Sea surgeon John Woodall recommended that "when the Omentum commeth out with all haste put it into his place least it corrupt, and the aire alter it"1. Military surgeon James Cooke agrees, explaining that when the protruding material is "not altered, but is warm, thrust it in, and stitch the Wound."2 Closing the wound is Step 2 of simple wound care. It would be followed by dressing and medicating the wound and using humor-based procedures such as bloodletting and proper diet to encourage healing.

Ambroise Paré gave a slightly different explanation of the problem of exposure of the viscera, noting that "the Guts having taken cold by the encompassing ayre, swell up and are distended with wind"3. This is echoed by military surgeon Richard Wiseman who warns that when "the Intestines or Omentum do thrust out, you must speedily reduce [replace] them, lest the former inflate, or the latter over-cool and corrupt."4 Here, air itself isn't the problem so much as the cold it brings with it. When this happens, the surgeon can still fix the problem and replace the omentum. Wiseman explains, "The Intestines and Omentum are disposed to Reduction by warm discutient Fomentations [liquids capable of disposing of diseased matter]"5.

For the medicines required to reduce inflated intestines, Paré recommends

Photo: Wiki User Alvegaspar - Melilot

a fomentation of the decoction of camomill, melilot, aniseeds and fennell applyed with a spunge, or contained in a [pig's] bladder; or else with chickens, or whelps [puppies] cut alive in the midst [of the wound] and laid upon the swelling; for thus they do not only discuss [dissipate] the flatulency [inflating air], but also comfort the afflicted part.6

Wiseman's recommendations are remarkably similar, adding a few other herbs to the mix. He suggests that

if the Gut be so pus[h]t out that you cannot return it in, you ought to foment it with warm Water, Red wine, or some discutient [dissipating] Decoction ex summit. origan. puleg. [tops of oregano] fol. beton. [betony flowers] salviæ [sage], flor. cham [chamomile flowers]. sem. anethi [dill seed], fænic. [fennel seed] dulc. anis. [sweet anise] &c.7

Notice that there isn't anything like dissecting chickens or puppies in front of the wound.

Another option is suggested by John Woodall. He reports that "if the intestins passe out by a wound, the wound being very little they will hardly be reduced [replaced in the abdominal cavity], unlesse they be pricked [and punctured], for they will swell with winde: but if the substance of a gutt be wounded [presumably by pricking it], sowe it together & consolidate it"8. Woodall's method would provide a quick solution, but it added the possible complication of having to suture the intestines.

Cutting an Existing Wound, Based on Johannes Scultetus,

l'Arcenal de Chirurgie (1665)

If these medicines fail to do the job, surgery is advised. Wiseman says "you must inlarge the Wound by Incision"9 while Paré orders that "the wound shal be dilated [further cut], that so the Guts may return the more freely to their place."10 Once replaced, the surgeon could proceed to heal the wound normally.

Wiseman discusses the full treatment of restoring the omentum in a case where a man was wounded across the stomach just below his navel on the left side. This case includes the post-operative treatments that follow standard healing procedures for simple wounds. Because this case is so thorough, it will be presented here in full. Paragraph breaks have been added to make it more readable.

The Omentum was much out; but not being altered by the Air, I caused warm Cloaths [cloth] presently to be held upon them very close, and the Patient to be placed low with his Head, and his Hips raised, and his Body somewhat declining to the right Side, my Assistent pressing with his hands something above the Wound, (by which the Lips of it were a little turned upward, and the Viscera kept down,)

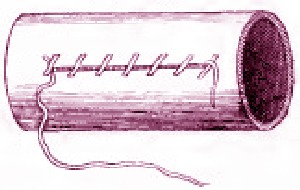

Suturing an Abdominal Wound, Johannes

Scultetus, l'Arcenal de Chirurgie (1665)

I prepared to stitch the Wound with a strong Needle somewhat curved at the point, threaded proportionably, taking hold of the lower Lip [of the wound]; and passed my Needle first through the Peritonæum, and then to the opposite side, through the Flesh and Skin, leaving the Peritonæum; and so along, taking it up on one side, and leaving it on the other, till I had sowed up the Wound. Then I pull'd the Stitches as close together as I could, and fastened my thread.

The Wound thus stitcht, I sprinkled the Stitches with pulv. [powdered] aloes, colophonia [rosin or greek pitch], sang. dracon. [dragon's blood resin] mastic. &c. and applied Sarcoticks [medicines to unite flesh] with a Plaister over all, made up of some of the aforesaid Powders cum. album. Ovi [with egg white] and with Compress and a strong Towel braced them all fast. ...I drest him after the same manner every other day; and when the Wound seemed to be cicatrized [healed with a scar], and that my Stitches began to fret, I cut them out the eighth or ninth day; but continued the use of Sarcoticks till it was firmly cicatrized.11

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 139; 2 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 133; 3 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 302; 4 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371; 5 Wiseman, p. 433; 6 Paré, p. 302; 7 Wiseman, p. 371; 8 Woodall, p. 139-40; 9 Paré, p. 302; 10 Wiseman, p. 371; 11 Wiseman, p. 372-3

Removing the Corrupted Omentum

When the viscera which had pushed its way out through the wound of the abdomen was beyond saving, surgeons from this era agreed that it had to be cut off before the wound could be healed. Separation was required when the surgeon found the exposed viscera to be dark-colored and hard as noted previously. Sea surgeon John Woodall explained that "if it [the exposed viscera] shall be put in cold it will putrefie, and bring grievous Symptoms, it were better to make a ligature [tie a thread tightly] about so much as is out, and cut it off being carefull of the guts"1. ('Being careful' here means not cutting through the intestines.)

String Left Hanging Out of an Abdominal Wound,

Based on

Johannes

Scultetus,

l'Arcenal de

Chirurgie (1665)

James Cooke recommended that the surgeon "bind it near the sound part [of the exposed viscera], cut it off, and leave the rest to fall off it self, leaving the thread [used to bind the corrupted part] out"2. Richard Wiseman explained that the wound was to be stitched up, the surgeon was to leave the thread or ligature "till it shall be cast off by Digestion."3 Ambroise Paré gives a slightly different recommendation for the string. He advises

whatsoever thereof is putrefied shall be twitched [pulled quickly] and bound hard with a string and so cut off, and the rest restored to his proper place: but it’s good after cutting of it away to leave the string still hanging thereat, that so you may pluck and draw forth whatsoever thereof may by being too strait [tight] bound fall away into the capacity of the belly. Some think it to be better to let the Kall [caul or greater omentum] thus bound to hang forth until that portion thereof which is purtrefied fall away of it self, and not to cut it off. But they are much deceived, for it hanging thus would not cover the guts, which is the proper place.4

Here, the string could be used to extract the ruined flesh, although this required keeping the wound open.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 139; 2 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 133; 3 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371 & 433; 4 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 302-3

Wounds of the Abdomen - Suturing

Suturing played an important part in wounds of the abdomen because it helped to prevent the viscera from pushing its way out through the wound and running the risk of becoming corrupted. Although stitching wounds was not unusual in any kind of large, simple wound, wounds of the abdomen did present a unique facet. As John Woodall explains, "outward wounds of the belly do nothing differ from the generall method of other wounds… only in stitching [do] they differ much"1. Military surgeon Richard Wiseman expands upon this idea.

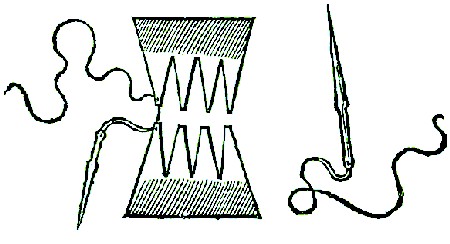

Dry Suture Tools, The Workes of..., Ambrose Pare, p. 293 (1649)

[B]y reason of the fatness, and thickness of the Lips [of wounds of the abdomen], and by [the] pressing of the Kell and Guts [against the abdominal wall], the stitching of the Belly is a troublesome work: and yet if the Wounds be not so stitched that the Peritonæum and Fleshy parts may unite together, a Hernia will follow... for the Peritonæum bears a great stress. Therefore you must be sure to take good hold with your Stitches: and if you doubt their holding, make dry Stitches over them, with good Bandage.2

Dry stitching involved gluing strips of linen to the skin on either side of the wound and then sewing the linen strips together. This was typically done to prevent the surgeon from having to suture through the skin and leave scars behind. However, as Wiseman explains, it is used in this case to support the typical through-skin suture and help resist the pressure of the organs within the wound.

Another important aspect of stitching the abdomen was the suturing technique used. Ambroise Paré calls for using "a seam as Furriers or Glovers use"3. French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis likewise notes the use of the

Glover's Suture, From A General System of Surgery,

By Lorenz Heister, Plate 4,

(1770)

glover's stitch in wounds of the intestines.4 He also says "if the wound be great and worth speaking of, it must be sowed with that suture which is termed Gastroraphia".5 This refers to using a large, straight, flat needle to make a glover's suture.

The stitch itself is fairly simple. Paré explains it thus:

The needle at the first putting in must only take hold of the Peritoneum, and then on the opposite side only of the flesh; letting the Peritoneum alone, & so go along putting the needle from without inwards, and from within outwards, but so that you only take the musculous flesh & skin over it, & then only the Peritonæum, until you have sowed up all the wound6

Military surgeon James Cooke recommends the glover's stitch as well, but with an added wrinkle. "First thrusting the Needle through the Skin and Muscles to Peritonæum, not touching it then from within outwards, pass through all,

Abdomen Suture, From Elements of Surgery, v. 2, By J. S. Dorsey (1813)

then tye it: Make another stitch an inch farther contrary to the first"7. The added step of tying off each stitch before proceeding to the next would have provided a little greater strength to the suture, although it would have made the suturing more difficult and time-consuming.

Cooke finishes his description of the suture by ordering the surgeon to "leave an Orifice to put in a Tent, dress it S.A. {according to art}."8 While the use of a tent in such wounds was unusual (as noted earlier), Paré himself recommends to the surgeon that "there must be left a certain small vent by which the quitture [discharges] may pass forth"9. He stops short of suggesting the use of a tent, however.

Paré also says that "the Chirurgeon shall not suffer them to be without medicines as if they were desperate, but here shall spare neither labour nor care to dress them diligently"10. The medicine he advises using is "a powder made of Mastich, Myrrh, Aloes and Bole"11. To relieve pressure on the wound, he also advises that the surgeon have "the Patient lying on the side opposite to the wound."12

Cooke advises the use of similar medicines on the intestines before replacing them. They are to be

first cleansed with warm water, sprinkling with this: Rx. Alo[es]. Mastic. Thur. [frankincense] Mum[mia]. [Dried mummy] Sang. Drac. [dragon's blood resin] {or each one dram} M.f. pul. [make into a powder] Take inwardly Mastich, which is profitable in all Wounds, especially those of the Stomach.13

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 139; 2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 373; 3 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 302; 4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 38; 5,6 Paré, p. 303; 7,8 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 133; 9,10 Paré, p. 303; 11,12 Paré, p. 302; 13 Cooke, p. 135

Wounds of the Abdomen - Medicines

Unlike other types of wounds, the description of medicines used to heal wounds of the abdomen after they have been sutured is somewhat limited. (In fact, most of the period surgeons seem to have expended the majority of their energy in describing the healing of wounds to the chest, with the healing of wounds to the abdomen running a very distant second.) This may also be due in part to the fact that healing a wound of the abdomen is just like healing most simple wounds once the problem of securing the omentum and intestines has been dealt with.

Richard Wiseman recommends vulnerary or healing medicines, which is the same type suggested by many of the surgeons treating simple wounds. Among those he suggests are:

Photo: R. Boroujerdi - Tragacanth

fol. Plantag. [plantane leaves] equiseti [Equisetum arvense or horsetail], pimpinell. [pimpinella, probably referring to anise] pilosell. [pilosella auricula or European hawkweeds] rad. consoled. [comfrey root] to which may be added cons. ros. rub. [conserve of red roses] cons. cydonior. [conserve of quinces] Bolus's [large doses of medicine] may also be proper of species diatragacanth. [a powder containing gum tragacanth and other herbs] with Balsamicks [medicines having restorative and curative properties].1

Fellow military surgeon James Cooke recommends applying a compound liniment to the healing wound.

Embrocate the pained part cum Ol. Ros. [oil of roses] Myrtin. [oil of myrtles] {of each ½ ounce} Lilior. [oil of lillies] Lumbric. [oil of earthworms] {of each 1 ounce} Ol. Cham. [oil of chamomile] Aneth. [oil of dill] {of each 6 drams} Unguent Dialth. Popul. [Unguent Nicholas] {of each 3 drams} M.f. Liniment. {make into a liniment}2

Many of these same medicines can be found in the prescriptions suggested by surgeons in the article on healing simple wounds.

1 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 372; 2 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 133

Wounds of the Abdomen - Humor Treatments

As with the discussion of medicines used after a abdominal wound has been sutured, the period surgical literature is somewhat lacking in material on the humor-based treatments following the operation. This is likely due to the similarity of humor-based treatments in abdominal wounds to those used in simple wounds. Many of the surgical writers had already discussed humor-focused treatments at length in of Step 4 of simple wound care: maintaining wound temperament.

In fact, Richard Wiseman is the only contemporary surgeon to give any amount of specific attention to humoral treatments in abdominal wounds. He first reports that "Venæsection [bloodletting] is necessary, and may be repeated as occasion shall offer."1 This has a ring of definitiveness and he does not expand upon it.

Artist: Wolf Helmhardt von Hohberg - The Patient's Diet (1695)

Wiseman has more to say about the patient's diet, which has an indirect tie to humors. "Regulation in Diet ought to be with great moderation... [such as] Chicken or Veal broth wherein Barly hath been boiled: to which may be added Yolks of eggs, mel. comm. [common honey] or Sugar of red Roses, &c."2

In these recommendations, Wiseman appears to be echoing the writings of revered ancient Greek medical writer Aulus Cornelius Celsus. Celsus advises "if the wound be severe, he [the patient] ought to abstain from food, as much as his strength will permit... but ...a regard must always be had to the strength of the patient; so that his weakness may render it necessary to take food immediately, but such [food] as is thin, and in small quantity, just sufficient to support him."3

Once the patient has been on Wiseman's diet for two days, he recommends that "Clysters [enemas] may be administred"4, a more direct humor-based procedure designed to purge the unwanted humors out of the digestive system.

1,2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 372; 3Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Of Medicine in Eight Books, 1756, p. 283; 4 Wiseman, p. 372