Torso Wound Care Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Next>>

Torso Wound Care During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Wounds of the Abdomen

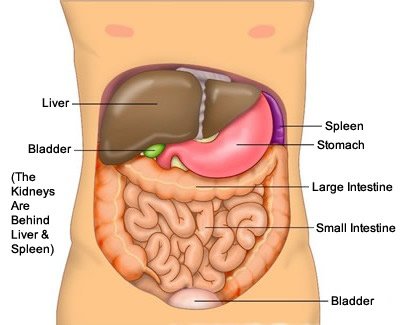

The abdomen is usually defined as the part of the torso which extends from the bottom of the

Artist: Ties van Brussel - Viscera (Organs) of the Abdomen

rib cage to the groin. The organs damaged by wounds of the abdomen which were primarily discussed by surgeons during this period are the stomach, small and large intestines, liver, kidneys, spleen and bladder. While considered serious and often deadly, wounds of the abdomen do not appear to have been considered as deadly as wounds to the thorax. French surgeon Ambroise Paré summed them up nicely, commenting:

The wounds of the lower belly are sometimes before, sometimes behind, some only touch the surface thereof, others enter in; some passe quite through the body, so that they often leave the weapon therein; some happen without hurting the contained parts; others grievously offend these parts"1

In addition to the organs themselves, there are two membranes in the adbominal cavity which are frequently mentioned by period surgeons when discussing these wounds. In order to understand their diagnoses and recommendations in wounds of the abdomen, it will be useful for the reader understand what and where these membranes are.

The first is the peritoneum, a membrane which lines the abdominal cavity, covering the viscera or internal organs there. Apothecary John Quincy explains this membrane as lying "under the Muscles of the lower Belly,

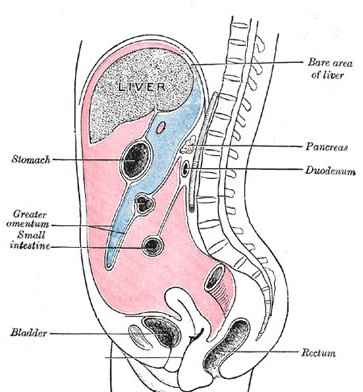

Artist: Henry Gray (Anatomy of the Body)

The Peritoneum (shown in pink) With Locations of Organs

and the

Greater Omentum (white line around blue area) Shown (pre-1858)

and is a thin and soft Membrane, which encloses all the Bowels contained in the lower Belly, covering all the Insides of its Cavity."2 It's contents are shown in pink in the cross section of the abdomen shown at right.

The second membrane mentioned in most of the texts from this era is called by a variety of names: caul (sometimes spelled 'kell' during this period), reticulum, omentum or epiploon. It is today referred to as the greater omentum. Apothecary John Quincy explains that it is a membrane located inside the peritoneum.

This membrane, which is like a wide and empty Bag, covers the greatest part of the Guts. Its Mouth is tied on the right side of the Hollow of the Liver, on the left side to the Spleen, backwards to the Duodenum [first part of the small intestine], and that Part of the Colon [part of the large intestine] which lies under the Stomach, and forwards to the Bottom of the Stomach and Pylorus [place where the stomach ties into the duodenum].3

The greater omentum is shown enclosing the area in blue in the diagram at right. With this information in mind, we can move on to the discussion of finding and treating wounds of the abdomen.

Like wounds of the chest, abdomen wounds were divided into two basic types: those not penetrating the cavity housing the organs and those which did. Penetrating wounds were obviously the dangerous ones, presenting the surgeon with a variety of problems in healing. While they certainly created internal problems, the surgeons of this era were primarily concerned with problems external to the abdominal cavity; surgeons during this period had very little to do inside the abdominal cavity because it was felt that exposing the organs to air eventually led to their ruin and the death of the patient.

The complication most discussed during treatment of abdominal wounds was the the 'falling out' of the organs and omentum through large wounds. Golden age of piracy surgeons believed that if this was caught soon enough, it could be restored to the abdominal cavity and healed. If not, the exposed portion of the omentum and any parts of the organ which came out with it had to be removed, the healthy portion restored and then treated. Let's look at these facets of abdominal wounds in detail.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 301; 2 John Quincy, Lexicon Physico-Medicum, 1726, p. 358; 3 Quincy, p. 341

Wounds of the Abdomen - Non-Penetrating

Artist: Gerrit Lundens

Surgeon attending a wound, Wellcome Collection (17th c.)

Like non-penetrating wounds of the chest, non-penetrating wounds of the abdomen were generally not considered dangerous. Military surgeon Richard Wiseman defines non-penetrating wounds of the abdomen as being those that "reach no farther inward than the Peritonæum."1 Wiseman also says, "Wounds not penetrating [the peritoneum] are without danger."2

Both Ambroise Paré and sea surgeon John Woodall state that these wounds are fairly simple to heal. Paré advises that wounds of the stomach "which passe no further than the Perionæum shall be cured like simple wounds which only require union."3 Writing to the surgeon's assistant, Woodall puts it more simply, "The outward wounds of the belly do nothing differ from the generall method of other wounds"4. Such wounds would follow the standard five step healing procedure outlined on the first page of this article and explained in detail in the article on simple wounds.

Wiseman does warn about one type of wound that may cause problems even when it does not penetrate the peritoneum. "Those [wounds] in the middle of the Belly are worst, by reason of the Nervous body that lieth there, and consequently [are] more painful to be stitched, and difficulter of Cure, by reason of the Intestines or Kell [caul] pressing most upon that Part."5 However, this warning seems primarily to have been included to warn the surgeon to be careful when following the simple wound procedure.

1,2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371; 3 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 302; 4 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 139; 5 Wiseman, p. 371

Wounds of the Abdomen - Penetrating

Penetrating wounds were considered the greater challenge to a surgeon. Richard Wiseman differentiates

Artist: Gaspare Traversi

Probing a Wound to the Abdomen, From 'The Operation', (1753-4)

between wounds of the abdomen that damage the internal organs and those which don't. He tells his reader that when treating small wounds "you must search it with your Probe"1 to verify that it does indeed penetrate the abdominal cavity. Fellow military surgeon James Cooke likewise explains that wounds that are "penetrating, are found out by the Probe, [and detected when they are] going deep downwards"2.

Wiseman goes on to say that when the omentum or organs are ot protruding through the wound, there are no signs that any of the internal organs have been wounded and "if there be neither Inflation of the Belly, Colick [a blockage in the excretory organs], Vomiting, or ought extraordinary [released] by Urine or Stool, you may conclude all well; and being so, your best way will be to heal up the Wound by Agglutination [bringing the wound edges together]"3. This is Step 2 or the simple wound healing procedure.

Wiseman warns against keeping such wounds open by artificial means (such as tents),

Artist: Alfonso el Sabio

Abandaging Patient's Abdomen, From the Wellcome Collection (13thc)

because "by exposing it to the external Air, Putrefaction, Colick, &c. may ensue."4 He advises healing 'with all expedition', keeping the patient in bed, "for in sitting up, the weight of the Bowels will stretch the Peritonæum, as to make a Hernia."5 He also recommends 'good Compression on the wound' [usually done using bandages] which would help keep the wound lips together so they could heal. This is Step 3 or the simple wound healing procedure.

If internal damage was caused by such penetrating wounds of the abdomen, the wound is of much greater concern. Wiseman warns that when "any of the internal Viscera [organs] be hurt the danger is great, all such cases being accounted mortal."6 While they may have been 'accounted' mortal, the surgeon would still do what he could for the patient and was sometimes rewarded for his efforts by the patient's survival.

There were a variety of issues which could arise in penetrating wounds of the abdomen, not the least of which was the 'falling out of the (grand) omentum'. Cooke advises that "if the Caul [grand omentum] and Guts start out, they are dangerous, sometimes deadly."7 This particular operation is discussed by nearly all the authors under study who were concerned with wounds of the abdomen, so it is handled in detail in the three sections that follow.

Artist: Pierre Boiaistuau

Air and the Intestines Don't Go Well Together in

the GAoP, From Histoires Prodigieuses, The

Wellcome Collection (1560)

Among the other problems associated with piercing abdominal injuries, air reaching the viscera was one of the most often mentioned by surgeons of this period. Ambroise Paré said that such wounds "are judged very dangerous, though they do not touch the contained bowels; for the encompassing and new ayr entering in amongst the bowels, greatly hurts them"8.

It may be due to the problems caused by air reaching the viscera that some authors advised against using tents in these wounds. When discussing a case where the abdomen was pierced without wounding any internal organs, Wiseman says that "if the Wound had been kept tented, it might have been subject to Inflammation, by reason of the disturbance there, from whence ill Accidents might have happened."9 Although this 'disturbance' doesn't specifically mention air reaching, 'inflammation' was believed to be one result of air reaching the abdominal viscera. Yet Wiseman says that in order to avoid being "condemned by the common vogue... some of our Profession, possibly against their own judgments, keep them tented often, to the ruine of their Patient."10

Paré lists another problem that can occur as a result of abdominal wounds. He explains that the 'filth' of the wound cannot be removed "whereby it happens, they divers times turn into fistula’s... and so at length by collection of matter cause death."11 Closely related to this, Paré warns that "the blood which is shed inwardly amongst the bowels putrefies and corrupts, whence followes pain, a feaver, inflammation, and lastly death."12

These problems identified by Paré could actually be used as an argument for keeping the wound open so that the unwanted substances could drain out, but this is not something Paré suggests. James Cooke does recommend leaving a space to insert a tent when suturing such wounds, apparently to allow for drainage.13 However, despite Paré's predictions of impending doom for patients with internally gathered filth and blood, he does admit "I have dressed many who by Gods assistance & favour have recovered of wounds [with the unwanted detritous] passing quite through their bodies."14

1 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371; 3 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 133; 3 Wiseman, p. 371; 4 Wiseman, p. 371-2; 5 Wiseman, p. 372; 6 Wiseman, p. 371; 7 Cooke, p. 133; 8 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 302; 9,10 Wiseman, p. 373; 11,12 Paré, p. 302; 13 Cooke, p. 133; 14 Paré, p. 302

Omentum Falling Out

When a penetrating wound was large, period surgeons often said that the caul or omentum would poke out of the wound.1 Although the words 'caul' and 'omentum' should technically refer to the grand omentum seen in the cross section at the top of this page, period authors sometimes also described this as being a thrusting out of the guts2.

Artist: Charles Bell

Sabre Wound to the Abdomen with Exposed Viscera, Wellcome, (1836)

Military surgeon Richard Wiseman explains that when "the Peritonæum be also cut through, it is reckoned a penetrating Wound; in which case, if the Wound be large, the Omentum or Intestines slip out."3 This is a more precise explanation of what actually happened since the intestines were not contained inside the greater omentum and anything protruding from an incised wound in the lower half of the stomach would likely be the intestines. However, most authors (including Wiseman in many cases) simply refer to this problem as 'the omentum falling out' which is how we will continue to refer to it here.

Surgeons from the golden age of piracy identified the problem as being that old villain external air.4 Ambroise Paré explained that when the caul fell out, "it is very subject to putrefie; for the fat, whereof for the most part it consists, being exposed to the ayre, easily loses its native heat, which is small and weak, whence a mortification [death of the part] ensue"5. He goes on to explain the symptoms. "The Chirurgeon shall know whether it putrefie, or not, by the blacknesse and the coldness you may perceive by touching it"6. Military surgeon James Cooke adds a bit to this, explaining that "from the cold Air it [the protruding viscera will] become black, livid or hard"7. The important distinction was that If the exposed viscera were still healthy and viable, it could be restored, but if it had putrified, it had to be removed before being restored or "the contagion of the putrefaction would spread to the rest of the parts"8.

1 For examples, see Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371, Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 302 & John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 139; 2 For example, see James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 133 & Paré, p. 302; 3 Wiseman, p. 371; 4 For examples, see Paré, p. 302, Woodall, p. 139, Wiseman, p. 372 & Cooke, p. 133; 5,6 Paré, p. 302; 7 Cooke, p. 133; 8 Paré, p. 302