Torso Wound Care Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Next>>

Torso Wound Care During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

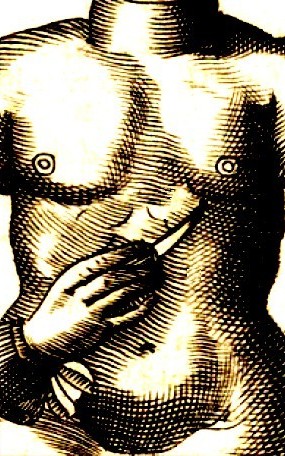

Wounds of the Thorax

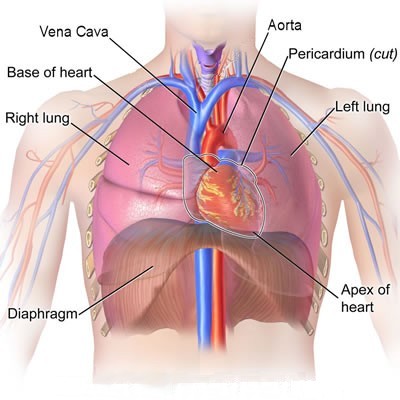

The chest (or thorax) is typically defined by these authors as the part of the torso which extends to about the bottom of the rib cage. It contains the lungs, heart and the diaphragm. Nearly all medical authors who discussed wounds of chest agreed that they were serious when they penetrated the chest cavity. Military surgeon Richard Wiseman noted that "all Wounds in the Breast are dangerous, by reason of the continual motion of the Lungs, and the bloud that falls down on the Diaphragma, and corrupts it."1

Artist: Blausen.com staff - Organs of the Chest/Thorax Cavity

Wiseman added that "Wounds in the hinder part of the Thorax are reckoned dangerous, by reason of the Nerves and Tendons"2 referring here apparently to the spine. German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann similarly warned about such problems. "The middle part [of the chest] abounds with Tendons, Nerves and Membranes, and is perforated in three several places, to make way for the Oesophagus, Vena Cava ascendens and Arteria Aorta; so that from hence we may readily conceive... what Pains and dangerous Symptoms may produce when it is wounded"3.

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis gave a more detailed explanation, identifying four problems he felt that occurred when healing such wounds.

The first [problem with healing wounds of the chest that occurs], because of the Entrance of the Air through the Wound without being modified of warm'd, as that is which passes through the Mouth, must in avoidably incommode the Lungs; Secondly, by reason that the continual Motion of the Breast opposes and obstructs the re-union which ought to be made; The third consists in the Difficulty of conveying Medicines to a Wound of the Lungs; and the fourth is, That the Matter has not a free Passage to come out of its self, and is not drawn out without Difficulty, when at the bottom of the Breast.4

Artist: Eduoard Hamman - Ambroise Paré Tending a Wounded Soldier

The problem of draining fluids from these wounds was a significant one, especially when combined with the idea in vogue at this time that air coming in contact with open wounds corrupted them. Richard Wiseman explained that surgeons who were in favor of "a speedy Agglutination [healing of the wound], do urge it, lest the internal Air corrupt the Part within, and the heat expire."5 French surgeon Ambroise Paré noted that such medical professions worried that "cold air [would] come to the heart, and the vitall spirits [which preserved life in the body] fly away and be dissipated."6

However, Paré also explains that other surgeons "think that such wounds ought to be long kept open ...that so the blood poured forth into the capacity of the Chest may have passage forth, which otherwise by delay would putrefie, whence would ensue an increase of the feaver, a fistulous ulcer, and other pernicious accidents."7 Wiseman explains his view of the two contradictory ideas using his own experience in treating these wounds.

In my practice, in these Wounds of the Breast, I consider the Wound, how it is capable of discharging the extravasated [leaking] Bloud and Matter. If it be inflicted so, that the Bloud or Matter may be thereby discharged, then it is to be kept open, the welfare of the Patient depending mainly upon the well dressing and governing it: but if it do not lie well for Evacuation of the extravasated Bloud, then it may do hurt, and so ought to be healed up.7

Artist: Antoine de Favray (1748) - From the Wellcome Collection

In fact, most of the surgeons under study who discuss puncturing wounds of the chest suggest likewise - keep the wound open to allow drainage unless it will not further healing. As a result, puncturing wounds of the thorax tend to follow the same five steps employed in curing simple wounds with the addition of a step after removing foreign objects from the wounds where the wound is to be kept open to allow for drainage and internal healing before healing the wound closed. In this way, it is like Step 2F in the healing of bullet and splinter wounds.

This section on wounds of the chest begins with healing non-penetrating wounds of the thorax. It then focuses on the procedures for handling penetrating chest wounds. These steps begin with detecting whether the wound penetrates the chest cavity. It then looks at ways to deal with bleeding from the wound. Such wounds were kept open to allow fluid drainage and internal healing of the wound using tents - pieces of cloth which were usually medicated. Medicines were administered both orally and at the wound site throughout the treatment of chest wounds for a variety of purposes, which are examined in detail. Humor-based treatments designed to remove or prevent the gathering of unwanted fluids at wounds site were then employed. This section finishes by discussing the treatment of two complications of penetrating chest wounds. The first is an empyema, or collection of fluids, particularly pus, in the chest cavity. The second is the formation of ulcers and tumors at the wound site.

1,2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 366; 3 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 116; 4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, p. 232-3; 5 Wiseman, p. 367; 6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 297; 7 Wiseman, p. 367

Wounds of the Thorax - Non-Penetrating Wounds

Wounds of the chest which did not penetrate into the chest cavity did not require any unusual treatment. As sea surgeon

Artist: Hans Friedrich Fleming - The Perfect Soldier (1726)

John Woodall explains, "wounds of the Thorax [chest] externall [not penetrating] suffer [need] to bee covered with flesh, and to be healed as other wounds"1. This recommendation is repeated by military surgeons Richard Wiseman2 and James Cooke3.

German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann agrees with this assessment, adding that small wounds "ought carefully to be observed in what part of it they happen, for [a]round the Body towards the Ribs it is Fleshy... [and] Wounds are not very dangerous in that part; if no other parts near it are injured, for they will easily be cured if carefully attended."4

French surgeon Ambroise Paré similarly advises that such wounds, "if they be only simple, may be dressed without putting in of any Tent [to keep the wound open], but only dropping in some of my balsam and then laying upon it a plaster of Gratia Dei [The Grace of God Plaster - made of turpentine, pitch, white wax, mastic, betony, vervain and burnet], or some such like, for so they will heal in a short time."5 Paré's recommendations are in line with the five steps outlined previously, the full details of which can be found in the article on simple wounds.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 139; 2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371; 3 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 129; 4 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, 1706, p. 116; 5 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 303

Wounds of the Thorax - Penetrating Wounds: Detection

Most of the surgeons who discussed wounds of the thorax mention methods for detecting whether the wound had penetrated the chest cavity. The most popular tool recommended was a candle.

Artist: Godfried Schalcken (1692-7)

Sea surgeon Hugh Ryder explained the way he used a candle in this capacity when confronted with three eminent surgeons who didn't believe the patient to be so wounded. Ryder says,

I desired one of them that he would please to take a Candle in his hand, and hold it near the Wound, which he did: Whereupon I advised the Patient to shut his Mouth, and hold his Breath, and immediately the included Air being forcibly expell’d [through the wound], blew the Candle out.1

Richard Wiseman suggests a nearly identical procedure using either 'a searching candle' or a down feather, explaining that when the patient held his breath it would rush out of the wound and "blow away the one, and extinguish the other."2 Military surgeons James Cooke3 and Ambroise Paré4 recommend similar procedures. In his account, Paré adds another sign of internal bleeding, explaining, "If the patient can scarce either draw, or put forth his breath, which also is a signe that there is some blood fallen down upon the Diaphragma."5 French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis descriptively advises that "if the Flame wavers or laves [washes – probably referring to flickering], 'tis a Sign that the Thrust [of a weapon] has penetrated the Breast, the Air which comes out being the only Cause of that small Motion."6

Some of the surgeons suggest methods in addition to that of the candle (or feather) for detecting such wounds. Dionis7 and Wiseman both suggest using a probe, "which enters into the Cavity"8. Dionis explains that

Probing a Chest Wound, From Jacques Guillemeau,

The French Chirurgerie, Frontispiece (1597)

"the most certain Proof of it is by the Probe; which if upon its Introduction enters the Cavity of the Breast, there is no room left to doubt that the Wound has penetrated."9 However, he also warns that if the weapon entered the chest cavity at an angle, "'tis not possible to guide the Probe into it... In this Case the Patient must be plac'd in the same Posture as when he receiv'd the Wound; and if the Probe does not then enter, the the [sic] Skin is to be externally dilated [enlarged with a knife or scalpel] without Delay."10 Placing patients into the same position they were in when receiving the wound is recommended by period surgeons to good effect in bullet wounds as well.

They both also advise the surgeon to look for blood which is "render’d frothy"11 at the wound site by the egress of air. Wiseman adds that, "The Air also makes a noise in its passing forth."12 Dionis explains that both the froth and noise are due to air "hurried out with some Rapidity by the Lungs which extend themselves, or by the Muscles which contract the Breast; when we cannot doubt of the Cavity being open, and also that the Lungs are wounded."13

Wiseman suggests an indirect method for detecting penetrating chest wounds. "Sometimes it is discovered by the quantity of bloud discharged by the Wound or Mouth, or both, with Difficulty of breathing."14 Dionis mentions a method he has seen other surgeons use, although he neither recommends nor advises against its use: "Others [referring to surgeons] say, that if the wounded Patient be very weak, a Looking-glass [mirror] is to be put before the Wound; and if it tarnishes, 'tis a Sign that Air comes out, and that the Wound is penetrating"15.

Still, Dionis clearly prefers using a probe to check for punctures reaching the chest cavity. The majority of the other surgeons appear to rely on the use of a candle at the wounds site.

1 Hugh Ryder, New Practical Observations in Surgery Containing Divers Remarkable Cases and Cures, 1685, p. 39-40; 2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 366; 3 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 129; 4,5 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 296; 6 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1733, p. 231-2; 7 Dionis, p. 231; 8 Wiseman, p. 366; 9,10 Dionis, p. 232; 11 Dionis, p. 231; 12 Wiseman, p. 366; 13 Dionis, p. 231; 14 Wiseman, p. 366; 15 Dionis, p. 232

Wounds of the Thorax - Penetrating Wounds: Detecting Internal Bleeding

Some of the surgical authors under study discuss the detection of internal bleeding in penetrating wounds of the chest. French surgeon Ambroise Paré has the most to say about such symptoms.

Surgeon Treating Open Chest Wound,

From Das Buch der Cirurgia des

Hieronymus Brunschwig (1497) Wellcome

We understand that there is blood poured forth into the capacity of the Chest by the difficulty of breathing, the vehemency of the increasing feaver, the stinking of the breath, the casting up of blood at the mouth, and other symptomes which usually happen to those who have putrefied and clotted blood at the parts to which it shall come.1

While discussing the treatment of a man wounded with a pike below his collarbone, sea surgeon John Moyle suggested similar symptoms indicated internal bleeding. While the patient's wound bled a lot, he bled "more inwardly; for he Hauk’d up much Blood, was very Faint, and Breathed difficulty."2

Paré adds a few other symptoms to this list including the patient's inability to lie on his back, his 'desire to omit' (probably referring to vomiting) and fainting when attempting to get up, which he says are due to the patient "being broken and debilitated both by reason of the wound, and concreat or clotted blood; for so putting on the quality of poyson, it greatly dissipates and dissolves the strength of the heart."3

The reference to poison here comes from humor theory which posits that blood can be corrupted at a wound site. (Blood is one of the four humors, the other three being phlegm, black and yellow bile.) Paré goes on to explain that an excess of blood and matter are formed in chest wounds due to their nearness to the heart, which continuously sends blood to the wound. "For this is natures care in preserving the affected parts, that continually and aboundantly without measure or means it sends all its supplyes, that is, blood and spirits to the aid."4 Once there, "blood defiled by the malignity and filth of the wound, is speedily corrupted"5.

1,2 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 297; 2 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 56; 3 Paré, p. 297; 4,5 Paré, p. 298

Wounds of the Thorax - Penetrating Wounds: Using Tents

Tents were folded and/or tied pieces of cloth which were inserted into wounds to keep them open and prevent the wound from healing too quickly for various reasons. These tents were often medicated.

Medical Tents With Threads and Large Heads, From Plate 2

of Lorenz Heisters' A General System of Surgery (1750)

Many surgeons recommended the use of tents in penetrating chest wounds particularly so that fluids such as blood and pus could be removed from the wound. Ambroise Paré explained that when "there is much blood fallen into the spaces of the Chest, then let the orifice of the wound be kept open with larger tents, untill all the Sanies [serum, blood and/or pus which is discharged by wounds] or bloody matter, wherein the blood hath degenerated, shall be exhausted."1 Here again we see a reference to the idea that blood was corrupted in the wound causing it to 'degenerate'.

Sea surgeon John Moyle likewise explains the using of a tent during the treatment of a chest wound. He notes that while the wound began to heal, "yet Blood [was] still spit up [by the patient] so that several Napkins [pieces of cloth] were wet in 24 Hours; I found it necessary to keep open the Orifice still, to evacuate the Gorie Matter. For which end I made a hollow Turunda [tent/drain] to permit the Matter continually to Issue out and the Implaster over it [to hold it in place] was jagg’d [probably meaning notched] for the same Intent; and the Patient lay so as to give the best Advantage for the Matter to come forth of the Wound."2.

Military surgeon Richard Wiseman says that his goal in using a tent in a piercing chest wound was "assisting Nature, by keeping a way open for the evacuation of what was extravasated [leaking] and corrupted within the [thoracic] Cavity, committing the Cure to her"3.

Moyle explains another purpose of the tent, warning the reader to be careful when a wound "runs much matter [fluids], and yet offers to heal too fast outwardly: Then keep it open whatever you do, until the bottom is first well healed."4 His concern here is that if the top of the wound heals before all the fluids have drained, a pocket of pus and other fluids will form at the bottom, creating an empyema due to the orifice of the wound healing too quickly.

Inserting a Tent, From l'Arcenal de Chirurgie,

By Johannes Scultetus, Table 37 (1665)

Other details of the makeup of these tents are explained by our period authors. In one of his case studies involving a young man who had been wounded in the breast, Wiseman explains that he made "made a soft Tent, with a Thread fastened to it; which in these Wounds you must be sure to do, lest you loose it in the Body."5 These tents were usually recommended to be short; Wiseman notes this in another of his case studies6 as does sea surgeon Hugh Ryder.7 Moyle advised says that such tents should be small8. He elsewhere warns his reader to be careful "lest your Tent should touch the Vitals [organs in the chest], and let it be but slender"9. Paré recommends that they should "also have somewhat a large head, lest they should be drawn as we said into the capacity of the Chest, for if they fall in, they will cause putrefaction and death."10

Most surgeons discussed using a variety of substances to medicate the tents placed in chest wounds. This will be explained in greater detail in the next section. The one exception to the notion of medicating the tent among the surgeons under study was German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann, who recommended using a dry tent with an Opodeldoch Plaster over it.11

While the surgeons of this time felt tents were useful in chest wounds, they still required judicious application. Paré warns his readers about leaving tents in chest wounds for too long, noting "that wounds of the Chest by the too long use of tents degenerate into Fistula’s."12 Fistulas are abnormal connections between organs or other open spaces within the body. As a result, Paré recommended that while penetrating wounds of the chest should be kept "open for two or three dayes; but when you shall find that the Patient is troubled with none or very little pain, and that the midriffe is pressed down with no weight, and that he breaths freely, then let the tent be taken forth, and the wound healed up as speedily as you can"13.

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 298; 2 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 57; 3 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 368; 4 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 56; 5 Wiseman, p. 367; 6 Wiseman, p. 369; 7 Hugh Ryder, New Practical Observations in Surgery Containing Divers Remarkable Cases and Cures, 1685, p. 40; 8 ,9 Moyle, Abstractum, p. 55; 10 Paré, p. 298; 11 Ryder, p. 40; 12,, 13 Paré, p. 298