Torso Wound Care Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Next>>

Torso Wound Care During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 8

Wounds of the Internal Organs

Little is said about wounds to particular organs within the thoracic and abdominal cavities. This is due at least in part to to the concern about air coming in contact with the organs, something which has been discussed. However, there are other factors at work here.

Artist: P. R. Vigneron - Aulus Cornelius Celsus

Revered first century Roman medical writer Aulus Cornelius Celsus advised, "In the bowels [referring to the abdominal cavity] nothing is to be touched" with the exception of cutting away that which protrudes out of existing wounds.1

In fact, much of what was actually is recommended in the care of wounds of the internal organs during golden age of piracy can be directly traced to statements found in Celsus' 1st century book De Medicina. Many medical men before and during the golden age of piracy felt that the books written by early authors such as Hippocrates, Galen of Pergamon and Celsus held all the information necessary to treat patients during this time.

This was not due to ignorance or lack of experimentation. But when authors such as Ambroise Paré discovered new ways of dealing with health problem, they carefully couched their explanations for these solutions in references to the revered ancient authors.2

It is also sometimes proposed that this reliance on the writings of ancient authors was due to a lack of understanding of anatomy as it related to the organs contained in the chest and abdomen. This sprouts from the (rather persistent) rumor that the church prohibited the opening of corpses in the middle ages. As a result, the layout of the organs was not familiar to later surgeons and physicians.

However, research reveals multiple examples of medieval examples of autopsies being performed.3 Harvard historian Katherine Park laments, "The myth of medieval resistance to dissection is an old one, and like the flat-earth myth with which it is often associated, it has proved protean and apparently impossible to kill."4 Paré specifically refers to the

Andraes Vesalius Dissecting a Corpse, From De Humani

Corporus, Frontispiece (1543)

anatomical detailed drawings printed by Brussels-born 16th century physician Andreas Vesalius in his 1543 book De humani corporis fabrica.5 So the layout of the anatomy was fairly advanced and well-understood by the end of the 17th century.

Although such wounds were often regarded with great concern and many were essentially considered mortal, there was still some hope that such patients could be cured, even though that was challenging. Celsus comments:

A person can't be preserved, when the basis of the brain, or the heart, or the gullet, or the [vena] portæ [short vein] of the liver, or the spinal marrow is wounded; or when the middle of the lungs, or the jejunum [middle of the small intestine], or smaller intestine, or stomach, or kidneys are wounded; or when the large veins or arteries about the throat are cut through. The cure is difficult in such as are wounded either in any part of the lungs, or the thick part of. the liver, or the membrane, that contains the brain, or in the spleen, or womb, or bladder, or any intestine, or the diaphagm.6

Several surgeons writing during the golden age of piracy say similar things. Military surgeon James Cooke advises, "Wounds of the Diaphragma, and Vessels [referring to the organs] there, are for the most part deadly."7 Sea surgeon John Woodall said that "if the liver, splene, stomacke, kidnies, or bladder be wounded, let nature worke his part, there is small hope by Arte [surgical and medicinal means] to prevaile."8 Paré gave perhaps the most comprehensive comment on this difficulty of cure of wounds of the organs:

So also the wounds of the Spleen, Kidneys, Ureters, Bladder, Womb and Gall [bladder], are commonly deadly, but alwayes ill, for that the actions of such parts are necessary for life; besides, divers of these are without blood and nervous others of them receive the moist excrements of the whole body, and lye in the innermost part of the body, so that they do not easily admit of medicins.9

It is probably for the best that surgeons didn't decide to explore the cavities of the torso in an effort to save patients. Without the equipment needed to keep the patient alive during open chest or abdominal surgery, the patient would most likely have died. However, without being able to view the wounded organs,

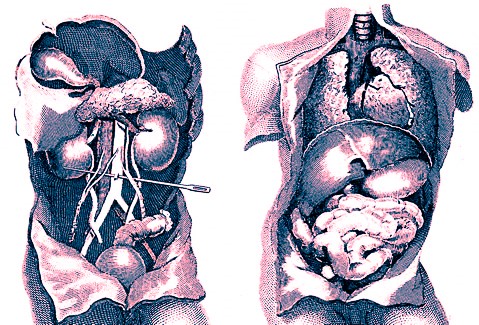

Artist: Richard Parker - Viscera Revealed, From the Wellcome Collection (1806)

the surgeons of this time were very limited in what they could do to assist the patient, which best explains their reliance on the comments from an author as ancient as Celsus.

It wasn't always even possible to know exactly which organs had been wounded, except by speculation. Military surgeon Wiseman said, "What internal Viscera are wounded, may be guessed by the external part hurt, but more certainly by their peculiar Symptoms."10

Despite their lack of direct knowledge of organ wounds and the crude diagnostic methods available to them, surgeons still had quite a bit to say about dealing with them. While much of what they said is rooted in the writings of Celsus, information not found in his work can also be found. With that in mind, each wound discussed by more than one golden age of piracy surgical author is discussed in its own section. This will begin with Celsus' comments on the organ and follow with comments from the golden age of piracy era surgeons. This part of the article will look at the following organs, roughly in order of their position within the torso from the top down: Heart, Lungs, Diaphragm, Liver, Kidneys, Spleen, Stomach, Intestines (large and small), Spine and Bladder.

1Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Of Medicine in Eight Books, 1756, p. 282-3; 2 For an example of this, see Paré's experimentation and resulting explanation about why boiling oil should not be used in fresh wounds in the article on cautarizing procedures; 3 Katherine Park, "The Criminal and Saintly Body: Autopsy and Dissection in Renaissance Italy", Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 1, Spring 1994, p. 1-10; 4 Park, p. 4; 5 See for example Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, pp. 135-7; 6 Celsus, p. 272; 7 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 132; 8 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 140; 9 Paré, p.585; 10 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 371

Wounds of the Internal Organs - The Heart

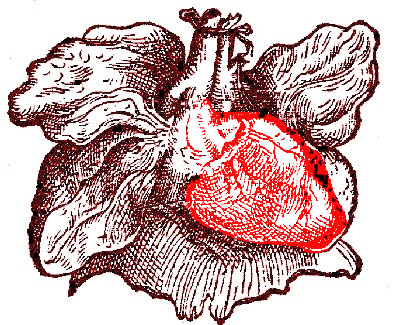

"When the heart is wounded, there is a great effusion of blood, the pulse is languid, the skin very pale, cold sweats with a bad smell come on, the same as in sickness: the extremities grow cold, and death quickly follows." (Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Of Medicine in Eight Books, 1756, p. 274)

Artist: Andraes Vesalis - The Heart, From De Humani

Corporus, p. 702 (1543)

Prognosis: The golden age of piracy surgeons who commented on wounds of the heart fairly well agreed that such wounds were mortal, which should not be very surprising. French surgeon Ambroise Paré reported in a case study of a man wounded in the heart during a sword duel kept fighting "until he fell down dead upon the ground; having opened his body I found a wound in the substance of the heart, so large as would contain one’s finger; there was only much blood poured forth upon the midriffe."1

Military surgeon James Cooke says that when "the Heart be hurt, ‘tis mortal, yea speedy death; If it pierce the right Ventricle, such not living twenty-four hours at most. If in the left, they may live longer. If only in the substance [of the heart] yet longer."2 You cannot help but wonder how he drew such specific conclusions.

Symptoms: Many of the reported signs of a wound to the heart are in line with those listed by Celsus. Both Paré and Cooke agree with Celsus that there is a lot of blood, the patient has a weak pulse, the limbs (or 'extream parts') get cold and the patient experience cold sweats. They both add that the patient trembles and faints (or 'swoons').3 Paré says that the patient "colour become[s] pale"4 while Cooke notes in a case study that the patient had a "wan Countenance (that always had been Ruddy)... an universal coldness had seized him; his Pulse was gone and so to all appearance past recovery."5

Photo: Andrewrp - Clove Gilleyflower (Dianthus caryophyllus)

Cure: Cooke does discuss treatment in the case study mentioned. He "used Frictions, till a handful of Salt came which I sent for; with which, rubbing his Lips for a quarter of an hour, his colour came, and he began to look up."6

He then gave the patient an six to eight spoonfuls of medicine 'several times' consisting of:

Rx. Aq. Borag[e]. Buglos. [Water of borage, a type of bugloss, believed to be good for cardiovascular disorders] Julap. Nurimberg. [a sweet, medicated drink from the Nuremberg Pharmacopoeia] {of each 1 ounce} aq. Cinam. [cinnamon water, thought to be good for the heart] {6 drams} Confect. Alker. [Confectio alkermes, used in faintings and said to comfort the heart] {1 dram} syr. Caryoph. [Syrup of Clove Gilleyflowers aka pink carnations, said to strengthen the heart] {1 ounce} M. [mixed].7

A definite focus in the ingredients chosen can be seen in Cooke's medicinals. He reported that this seemed to help, but the patient's fever increased the next morning, so he let him blood. This did not help, so he bled him again and then the patient died. After performing an autopsy on the patient, Cooke reported that the weapon "had passed through the Diaphragma into the point of the Heart, almost to the right Ventricle, and the Stomach drawn up above the Midriff."8

1 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, pp. 296; 2 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 129; 3 Paré, p. 296 & Cooke, p. 129; 4 Paré, p. 296; 5 Cooke, p. 129-30; 6,7,8 Cooke, p. 130

Wounds of the Internal Organs - The Lungs

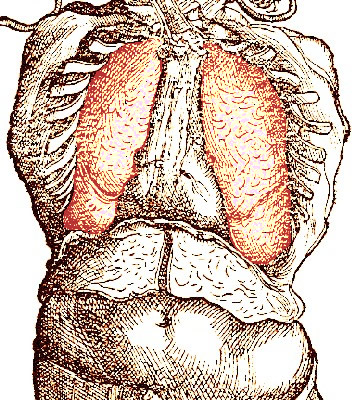

"When the lungs are wounded, there is a difficulty of breathing; frothy blood is discharged from the mouth, and red blood from the wound; also along with the latter the air issues with a noise; the patient has an inclination to lie upon the wound; some start up without any reason. Many when they are lying upon the wound are able to speak: if upon another part, they lose that faculty. ” (Aulus Cornelius Celsus, Of Medicine in Eight Books, 1756, p. 274)

Artist: Andraes Vesalis

The Lungs in the Body, From De Humani

Corporus, p. 702 (1543)

Prognosis: Wounds of the lungs were considered potentially curable. Richard Wiseman warns that when they are "wounded deep amongst the great Vessels, though they escape the first nine days, yet they commonly terminate in a Phthisis [tuberculosis], or Fistula."1 James Cooke says they may be healed "if only wounded in the Fleshy part."2

Ambroise Paré takes a middle ground, explaining that "A wound made in the Lungs admits cure, unless it be very large, if it be without inflammation; if it be on the skirts [edges] of the Lungs, and not on their upper parts; if the Patient contain himself from coughing much, and contentious speaking, and great breathing"3.

Most of Paré's last three conditions for survival are concerned with restricting the movement of the wound - coughing, forceful speaking and deep breathing. He goes on to explain how such things enlarge the wound and cause inflammation. As a result, "the ulcer is dilated, the inflammation augmented, the Patient wastes away, and the disease become incurable."4

Symptoms: Paré and Cooke list the symptoms of a wounded lung, several of which agree with Celsus' symptoms. These include frothy blood at the wound site (caused by air expelling out of the wound) and wanting to lay on the side where the wound is located.5

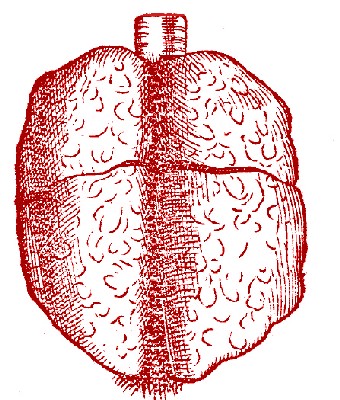

Artist: Andraes Vesalis

The Lungs Removed, From De Humani

Corporus, p. 707 (1543)

Paré also agrees with Celsus that the patient has difficulty breathing and can sometimes speak more "easily and freely" when lying on the wound, "but turned on the contrary side, he presently cannot speak."6 While Celsus notes that blood at the wound is red, Cooke says "the Blood issuing out is yellowish"7. Paré adds to Celsus' list that the patient has a cough and a "pain in his side, which he formerly had not"8.

Cure: In keeping with the possibility of curing wounds of the lungs, Cooke and Wiseman each discuss a remedy. Wiseman presents a case study where a rapier was thrust downward into the right side lung while Cooke presents a more general regime.

In his case study, Wiseman places a lot of emphasis on bleeding the patient. He explains that his patient had been let blood twice when he took over and he "presently let him bloud about ten ounces". He then prescribed a medicine (described shortly) and left. The next day the patient he and the attending physician "bled him again, taking away about {9 ounces} of bloud"9. Cooke does not suggest bleeding at all in his cure, relying primarily on medicines.

The medicine that Wiseman ordered an apothecary to give the patient in the previous paragraph contained:

Poppy Crop. Papaver Somniferum var Album - Malwa. India

aq. papaver. [poppy water, an opiate probably given for the pain and to help the patient sleep] cum syr. de meconio [diacodin, another opiate] & de ros. siccis. [syrup of dried roses] with a little aq. Saxoniæ frigid [a complex medicine used to 'cool the blood' and procure sleep].10

Wiseman's goal with this medicine seems to have been to help the patient sleep more than anything else. It worked and when he returned "in the morning, I found the Patient marvelously relieved... found his Wound small, and healed up within, but not cicactrized [healed over]"11.

Cooke gives quite a bit of detail on the medicines he suggests for wounds of the lungs, most of which was discussed in the section on treating wounds of the thorax. He first gives a general recommendation on the types of medicines that should be used: "Sharp things [medicines] are hurtful: Those comforting and drying are good."12 He then proposes a plan that follows that suggested for all wounds of the thorax. (See the sections on Topical Medicines and Using Drains to Remove Fluids for more information.)

Wiseman has one other, rather interesting comment on wounds of the lungs. In treating his patient with the rapier puncture, he found the wound to be at such an angle "that it was not capable of discharging the Matter, and so not worthy of my attendance, the Cure indeed consisting in internal Prescriptions."13 This refers to the fact the medicines were actually not normally under the purview of the surgeon. Physicians were responsible for prescribing medicines, particularly those to be administered internally. Because few ships had physicians, however, this would still have been the responsibility of the surgeon at sea.

1 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 366; 2 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chiururgery, 1693, p. 132;3,4 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, pp. 299; 5 Cooke, p. 130 & Paré, p. 296; 6 Paré, p. 296; 7 Cooke, p. 130; 8 Paré, p. 296; 9,10 Wiseman, p. 370; 11,12 Cooke, p. 130; 13 Wiseman, p. 370