Cereal Grains in Sailors Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 <<First

Cereal Grains in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 4

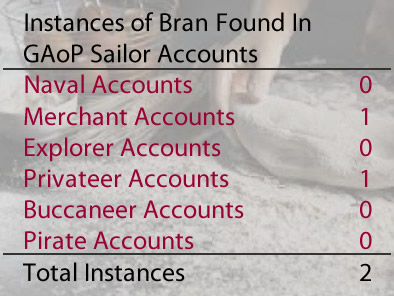

Bran

Called by Sailors: Bran

Appearance: 2 Times, in 2 Unique Ship Journeys from 2 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Buru, Indonesia;

As explained at the beginning of this article, bran is the edible, darker-colored outer layer of a cereal grain. For barley, oats, rice and wheat it is brown, for corn it is yellow and for millet it can be white, grey, yellow, red or brown, depending on the color of the millet grain. Bran was removed from grains by stone milling and sifting during this period. "Technically, when milling with stones... one must first mill in such a way as to minimize the pulverization of the bran and germ - the seed's outer coating and the granular structure that is the site of germination – and then have graduated sieves and fine cloth capable of separating the starch from the meal that is the product of milling."2

It was understood during this period that bran was not limited to wheat, but came from a variety of cereal grains. Elisha Coles Etymological Dictionary explains that bran is "the Husk of Ground Corn."

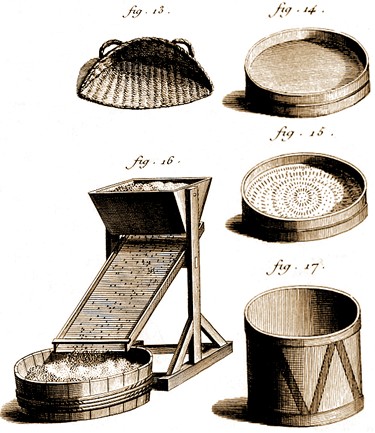

Sieves and Winnowers, From l'Encyclopedie, Tome 2,, p. 154 (1751)

13 & 14. Winnower, instruments intended to stir or winnow the grain,

to

remove

dust and refuse. 15. Hand sieve, an instrument pierced with small

holes

through

which grain passes, while moving it in a circular motion, the grain

which

is

cleaner than it could have been by the winnowing basket. 16. Foot Sieve,

hopper used the same way as the hand sieve. 17. Gauge for measuring grain.

(Note that his dictionary defines corn as "Grain of Wheat, Barley, Rice, Oats, &c. Note that Maize is conspicuously absent.)3 Or, as vegetarian and food activist Thomas Tryon points out, "the branny and husky' part is good in any Grain"4.

Despite Tryon's enthusiasm for it, bran was not highly valued as food during the golden age of piracy. In 1755, Samuel Johnson noted that it was "the refuse of the sieve"5 after cereal grains were ground. He goes on to provide three examples from seventeenth century literature, each of which disparage this nutritious outer grain layer. As Shakespeare's play Coriolanus says, "Yet I can make my audit up, that all, From me do back receive the flour of all, And leave me but the bran."6 This shouldn't be surprising given the popular emphasis given to the whiteness of bread. As French botanist Louis Lémery says, "The less Bran you leave in the Wheat Flower; of which you make Bread, the more nourishing and better tasted the Bread will be"7.

Lémery does not completely dismiss bran, however. He also says "The best [bread] is that made of good Wheat Flower, wherein they leave a little Bran, which is well kneaded, and sufficiently fermented, and lastly, well baked, with a moderate heat, so that it ought not to be neither too hard, nor too soft."8 Thomas Tryon says, "when the finest Flour is separated from the coursest and branny parts, neither the one nor the other, have the true Operations of the Flour of Wheat."9

Bran in oatmeal was defended several decades before the period.

Coarse Oat Bran

Gervase Markham explains, "There is againe another meate [food] to be made of Oate-meale, which is... somewhat more course and lesse pleasant... having both the bran and huls in it, yet is accounted a food of very good strength, and exceeding wholesome for mans body, and to my knowledge much used and much desired of all labouring persons that are acquainted with it"10. Note that the 'hull' of a grain is the bran. This explanation comes out of Markham's book, The English House-Wife, where he elaborates on the 'labouring persons' who have those who have "strong able stomackes, and such whos toyle and much sweate both liberally spendeth evill humours, and also preserveth men from the offence of fulnesse and surfiets."11 Although not a glowing recommendation of foods containing bran, this description could easily apply to a sailor. The makeup of oatmeal for the navy is nowhere near as well defined as the makeup of flour and likely contained bran, particularly when it was whole oat bran. Still, bran is more often mentioned as food for horses at this time than for people.

This may explain why bran appears so seldom on vessels during this period.

Photo: Peter Isotalo - Food Casks & Galley, 17th c. Vasa Model

The first of two mentions appears in a list of victualling stores for the Mary Galley which was headed for the East Indies in 1704. Among the initial victuals, they took aboard 30 bushels of "oats, barley and bran"12. The fact that oatmeal is listed separately and all three grains are are listed together sort of makes it sound like feed for live animals, although none are listed in the ship's documents available to us. So it is assumed here to have some value as food. The other instance comes from William Funnell's voyage in the privateer St. George in May of 1705. The vessel was in the East Indies and low on food. Funnell reported "we by a general consent shared all that was Eatable on Board our Vessel; and the whole of what each Mans share amounted to, was six Pound and three quarters of Flower, with five Pound of Bran; which how long it was to last, we could not tell"13. This makes it sound as if bran was only eaten in desperation, something that agrees with the idea that it was considered poor food. However, it does beg the question, why was the bran aboard to begin with?

Most of what is said about using wheat bran in food has to do with bread. "“White bread was favoured over bran breads, with the exception of the occasional need for bulk to help pass too compacted a stool. Loaf breads were favoured over flat breads. Wheat was favoured over all other grains.”14

Coarse Wheat Bran Bran

Some oat bran would have almost certainly been left in the oatmeal of the period; as Markham points out, purposefully leaving in more bran made the meal less enjoyable, but could be appropriate for hard workers like sailors. However, good oatmeal, like good bread, was perceived to have a minimum of bran in it.15 Oats were purchased on contract by the navy during this period and it is likely that some of them supplied 'inferior' oatmeal with an excess of bran because it was cheaper to supply, although no evidence of this was found.

Being a processed food, most period and near-period botanists and physicians have little to say about bran's humoral properties. Sea surgeon John Woodall says wheat bran is hot in the first degree.16 This is the same humoral quality that Galen gives wheat.17 Lémery mentions that wheat bran is 'cooling', although this probably shouldn't be taken as an indication of its humoral properties, particularly because he subscribed to the Paracelsian view of humors which didn't rely on hot/cold and dry/moist humors. English physician Thomas Cogan says that "Browne bread, made of the coarsest of Wheat flower, having in it much branne... when the meale [is] wholly unsifted, branne and all is made into bread, filleth the belly with excrements, and shortly descendeth from the stomacke."18 'Excrements' in the stomach were believed to beget bad humors which caused illness.

Bran, particularly wheat bran, did have an important place in medicine, even among sea surgeons. Sea surgeon Woodall counted wheat bran among the medicines he included into the surgeon's chests he prepared for the East India Company and the Navy in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Wheat bran was suggested to have a drawing faculty, making it useful in external applications as a cataplasm. Botanist John Gerard said wheat bran "dissolveth the beginning of all hot swellings,

Artist: Jost Amman -

A Grain Miller, From Das Standebuch (1586)

if it be laid unto them. And boyled with the decoction of Rue, it slacketh the swellings in womens breasts."19 Physician William Salmon said it "discusses [disperses] Tumors, being laid hot thereon in form of a Cataplasm, made with Vinegar, a little Salt, and Brandy."20 Botanist John Parkinson suggested that it "stayeth all inflammations, it helpeth also the bitings of Vipers, and all other venemous creatures.”21 Woodall explained that bran was "good against the scurfe [flaking of the skin], itch, and spreading scab, dissolveth the beginning of hotte swellings"22.

Several authors noted that wheat bran had a cleansing quality. Lémery calls it detersive and both Gerard and Parkinson advised that being "steeped in sharpe Vinegar and then bound in a Linnen cloth and rubbed on those places that have the morphew, scurfe, scabbe or leprosie will take them away".23 Tryon supported including it in bread because, it "contained the opening 'and digestive Quality, and there is as great a necessity of the one, as the other, for the support of Health"24. And if it worked going down, it must work coming up. Salmon outlined a clyster (enema) "made by boiling the Bran [of Wheat] (not too near Sifted) in the Broth made of a Sheeps Head and Gathers [entrails]; which being exhibited, does open and cleanse the Body of sharp and crude Humors, and to ease the Griping pain of the Bowels"25. Woodall likewise recommended a bran clyster as a "singular good the decoction thereof to cure the painefull exulcerations in the internalls ...as is mentioned in the cure of Disenteria [dysentery]."26

1 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p, 195; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 248; 2 William Rubel, Bread: A Global History, 2011, p. 15; 3 Nathan Bailey, "Brann" & "Corn", An Universal Etymological English Dictionary, 1724, not paginated; 4 Thomas Tryon, The way to health and long life, 1697, p. 137; 5 Samuel Johnson, "Bran", A dictionary of the English language 1st part, 1755, not paginated; 6 Coriolanus, shakespeare.mit.edu, gathered 3/6/23; 7 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 70; 8 Lémery, p. 68; 9 Tryon, p. 135; 10 Gervase Markham, Markham's Farewell to Husbandry, 1631, p. 131; 11 Markham, The English House-Wife, 11631, p. 242; 12 Bowrey, p. 195; 13 Funnell, p. 248; 14 Rubel, p. 16-7; 15 "Groot is nothing else but Oats divested of its Husk and outer Parts, and made into large Meal by the means of a Mill.", Lémery, p. 64; 16 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 118; 17 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1122; 18 Thomas Cogan, Haven of Health, 1636, p. 19 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 66; 20 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 945; 21 Parkinson, p. 1113; 22 Woodall, p. 118; 24 See Lémery, p. 70, Parkinson, p. 1113 & Gerard, p. 67; 25 Tryon, p. 135; 26 Woodall, p. 118

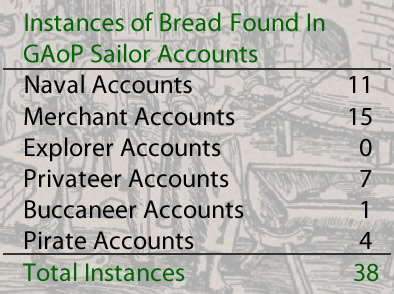

Bread

Called by Sailors: Biscuit, Bisket, Biskett, Bisquet, Bread, Nova Spain Bread, Rusk

Appearance: 38 Times, in 29 Unique Ship Journeys from 28 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Milford Haven, Wales; Kinsale, Ireland; Marseilles, France; Alicante & Rota, Spain; Livorno, Malaga & Messina, Italy; Alexandria, Egypt; Tripoli, Libya; Cape Coast Castle, Africa; Maio & Santiago, Cape Verde Islands; Bengal, Surat, India; Jakarta, Indonesia; Rantopanjang, East Aceh; Jamaica; Manzanillo, Mexico; Bahia Concepcion, Inuique & Juan Fernandez Islands, Chile; Guayaquil, Ecuador; Galapagos Islands; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Florida, New York, Rhode Island & Virginia, North America;

Bread is the single most important food made from processed grains to sailors during this period. It appears more often than any other processed grain food in these accounts, the others being flour, pasta and oatmeal (pasta is discussed under wheat and oatmeal under oats entry

Photo: Alexis Pantos - Fireplace Used to Bake Early Bread in Jordan, c. 12,000 B. It also appears in more sailors accounts than any of the individual grains.

Bread has long been part of humanity's diet; it "stores easily and is transportable, offering significant practical advantages over porridge and alcoholic fermentation for the primary use of the grain crop."2 Archeological digs have found traces of grain preparation and cooking dating to before the invention of agriculture."Starch grains from barley and possibly wheat imbedded in a grindstone found by the Sea of Galilee at the Upper Paleolithic site of Ohalo II are between 22,500 and 23,500 years old."3 It is likely because of bread's ability to travel and (not fully understood) high carbohydrate content, that it has been a part of the English naval diet since the beginning. It appears as early as 1545. The schedule of food given to General Surveyor of Victuals Edward Bashe in 1565 specified that the navy sailors were to receive "either a pound of biscuit or a wheaten loaf of 20 oz."4

Bread found in the accounts of long-distance sailors can broadly be divided into three types: loaf bread, biscuit and rusk. Let's consider each.

1 John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 14, 30, 32, 40 & 58; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 270 & 550; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 194; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol. 1, 1712, p. 324; Cooke, A Voyage..., Vol. 2, p. 60; John Covel, "Diary," Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 115; Daily Courant, 8-8-22, Issue 6489; Jonathan Dickenson, God's Protecting Providence, 1700, p. 49; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 128; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 97; Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 88 & 89; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 23, 99 & 255; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 75; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 93; The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., November, 1919, p. 205; The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., January, 1920, p. 3; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 98 & 297; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 197; Ravaneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 402; Stephen Martin-Leake, The Life of Sir John Leake, 1920, p. 222; Pyrates Lately taken by Captain OGLE", 1723, p. iv; Jeremy Roch, "The Diaries of Jeremy Roch", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 127; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 426; Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, 1825, p. 200; Silas Told, An Account of the Life, and Dealings of God with Silas Told &c., 1786, p. 14-5; 2,3 William Rubel, Bread: A Global History, 2011, p. 12; 4 David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 203

Loaf Bread

Of the three types of bread, loaf bread had the least utility at sea on long voyages because it didn't last more than a week or 10 days. It was removed from the naval specifications at some time between 1565 and 1636. A victualling contract was drawn up in January of 1636 with John Crane, Officer of the Admiralty and Marine Affairs and Surveyor General of all Victuals for ships which spelled out a meal plan that read "for every man one pound of biscuit"1. However, loaf bread returned to the sailor's menu in 1701

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

Lading a Small Ship, The Port of Landerneau seen from Saint Julien (18th c.)

when the navy, in an effort to serve healthier fare, decided that when ships were "in harbour, bread in loaves and fresh meat with salt to corn it are to be provided in lieu of biscuit and salt beef or pork."2 This was reiterated by the victualling board in 1703, who said, "when in petty warrant victualling [aka. in port], the constitution thereof is fresh meat, and bread in loaves. These, together with a continuance of paying short-allowance money, as at present practised (wherewith they will buy roots [root vegetables] and other refreshments), leads us to think the same in its present usage a very good and wholesome state of victualling."3

Sailors could also get loaf bread when they were in foreign ports, provided they had money for it, this being more appealing to them than their biscuit ration. Navy clerk John Baltharpe mentioned what was almost certainly loaf bread being sold along with wine, fresh fruit and cheese to the foremast men on HMS St. David when she was in port at Alicante and Rota in Spain as well as at Livorno and Messina in Italy.4 Similarly, Edward Barlow says he found "indifferent good bread and plenty" along with wine and oil in Marseilles, France when the Marey Gould merchant stopped there.5 Merchant John Covel explained that he ate fresh bread and wine when the London Merchant stopped in Malaga, Spain in 1673.6 Using the records of merchant vessel Viner Frigott, historian Peter Earle explains that "[i]n Alexandria, where a long time was spent taking in cargo, food was bought fresh week by week and consisted mainly of mutton, beef, rice, beans, fresh bread - 756 loaves a week for about 32 men "7. He similarly mentions that the merchant Upton Galley ate fresh bread as part of their weekly rations in Bengal, India in 1701.8

It is impossible to say for certain what grains these foreign breads might have used. Most were probably wheat grain bread because it would be the whitest and most appealing to Europeans who regarded it as the best, although they might have had other, cheaper grains in them to reduce the cost to the sellers. Not all bread which sailors ate was wheat bread

Millet Bread

. After being shipwrecked on the Florida coast and taken up by Spaniards in April of 1696, passenger Jonathan Dickenson reported that they "having not above a rove of corn [maize], and a little Nova Spain bread, which was so bad that it was more dust and dead weevils than bread: [yet] an handful of it was an acceptable present to us."9 The meaning of 'new Spain' bread could be debated, although it likely refers to corn bread given the location and plethora of Native Americans the Spaniards would have had to trade with. Merchant sailor John Covel goes into some detail about the bread available to the sailors on the London Merchant when they were in Turkey in 1670.

They make some of it of pure good wheat, most of it of millet, some of what we call Turkish wheat (maize), much of barley flour, and lighten it with leaven of salt and sower'd honey and oil, which give' it a brackish taste, yet it is not unpleasant whilst it is new. They bake it flat, with a rising in the middle like a coppled [Footnote 1: with a peak or cop, sugar-loaf form] cake. Every ship stored themselves from hence with what they wanted of sea provisions.10

In the Mediterranean, "every ship" would have included both navy and merchant vessels at this time.

Bread sold in England had to be made of wheat according to the 'Assize of Wheat', the original of which, 'Assisa Panis et Cervisæ'

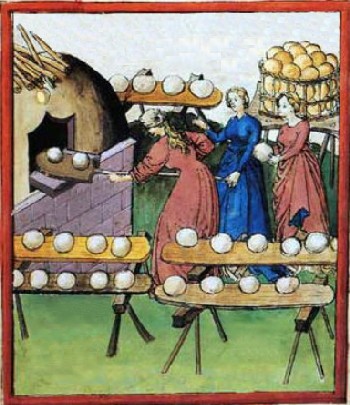

Making Brown Bread, From Tacuinum Sanitatus (15th c.)

is generally thought to have been put in place around 1266. It specified that bread in England was to cost a penny and that there be three 'grades' of wheaten bread sold. The three types of bread were specified as: 'wastell', (called 'white' bread by the golden age of piracy), 'bread of the whole wheat' (called 'wheaten' bread by the GAoP) and 'bread treet' or 'household' bread. The size of the loaves varied by the quality of the ingredients. The lowest quality, household bread, made with inferior flour, was the largest. Wheaten (or 'standard wheaten') was the medium quality bread made from wholemeal wheat and was three quarters the size of household bread. White (actually cream colored) bread was made with wheat that had been 'bolted' or sieved through a fine cloth and was three-quarters the size of the wheaten bread.11 Other 'unofficial' ingredients might include cheaper grain flour made from barley, rye or peas, but they would make the bread browner so could probably only be used in the household breads.12 "By the end of the seventeenth century, this, like all other regulations, had to a great extent fallen into desuetude. 'Little or no observance', recites the Parliament of 1710, 'had in many places been made, either of the said Assize, or of the reasonable price of bread.'"13 As a result, regulations were changed to base the price of bread either on that of wheat or wheat flour and the sizes of the loaves the bakers must supply were reduced. However, this would not be the same loaf bread as was provided by the navy who either baked their own bread or had mills contracted to make it. The naval bread was only to be made form the highest quality flour as spelled out in the various naval contracts.13

1 CSP Domestic, 1636-7, 1867, p. 452; 2 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 254; 3 Merriman, p. 268; 4 John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 14, 30, 32 & 40; 5 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 270; 6 John Covel, "Diary," Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 115; 7 Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 88; 8 Earle, p. 89; 9 Jonathan Dickenson, God's Protecting Providence, 1700, p. 49; 10 Covel, p. 120; 11 Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, pp. 15-6 & Beatrice & Sidney Webb, "The Assize of Bread", The Economic Journal, Vol. 14, No. 54 (June, 1904), pp. 197-8; 12 MacDonald, p. 17; 13 J. R. Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution: Part II 1673-1679", The English Historical Review, Vol. XIII (1898), p. 32; 14 According to the 1677 Victualling Contract, naval biscuit bread was to be made from "good, clean, sweet, sound, well bolted with a horse cloth, well baked and well conditioned wheaten" flour. (J. R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 166) The same flour would be used to bake loaf bread once it was required by the navy beginning in 1701.

Biscuit

The second type of bread, the most important to long distance sailors, was biscuit. As previously noted, the use of biscuit in the navy during voyages goes at least back to a victualling contract drawn up in January of 1636 which specified that each sailor was to receive a pound of it. In 1677, the description of the biscuit found in the Victualling Contract had been dramatically expanded; every sailor was to daily receive "one pound avoirdupois of good, clean, sweet, sound, well bolted with a horse cloth, well baked and well conditioned wheaten biscuit'."1 This should have resulted in a flour grade equivalent to England's white bread, provided the contractors did not cheat.

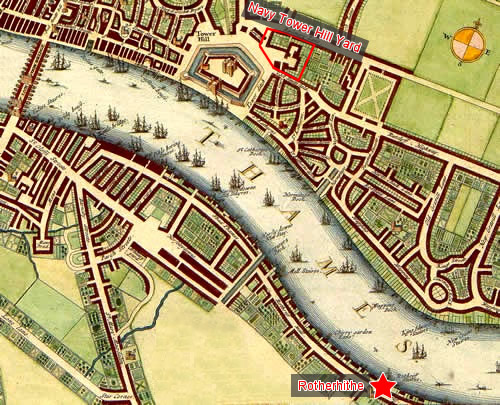

Navy Tower Hill Yard (Approximate Location) and Rotherhithe

Image:

Section of a Map of London, By Wencesclas Hollar (After 1688)

During the golden age of piracy, the navy tried to bring biscuit baking into their facilities rather than contract it out. Their bakehouse was initially located in their London Tower Hill yard. It proved to be inadequate for the amount of biscuit required, particularly during periods of war, so the navy leased mills at Rotherhithe, to the southeast of the Tower Hill yard. When the leases came up for renewal in 1713, the Admiralty mentioned some interesting things about their reasons for wanting to process wheat in house. "[S]ince the said mills are very convenient for her Majesty's service, and ...by her Majesty having mills to grind her own corn [referring to wheat2] therewith, there will not only be a saving in dear years [when wheat was expensive], but the too frequent practices of the millers in changing corn [using something other than the 'best' wheat in the biscuit] will be thereby prevented."3

The term 'biscuit' is often taken to mean twice-baked bread, with modern authors typically citing the French etymology of the word where , “bis” means “twice” and “cuit” means “cooked”. And, during the middle ages, this was indeed the case.4 However, possibly in an effort to speed up the cooking process, to increase throughput as well as produce more durable [harder] bread, the English navy modified the process to produce a similar result. "The bread was baked into thin cakes of biscuit weighing about five to the lb. The finished product was placed in a dry warm loft for fourteen days before being filled into bags."5 This secondary warming apparently dried the biscuit out more than even twice baking, based on William Dampier's assertion that rusk (the name the English typically gave to twice baked bread) was not as hard as biscuit.6 As late as 1775, Benjamin Franklin commented, "The ship biscuit is too hard for some sets of teeth. It may be softened by toasting."7 One would think that toasting would make the biscuit even drier, if that was possible.

An outline of the baking process was sent by the Victualling Committee to the Secretary of the Navy in July of 1715, which is quoted in part by Daniel Baugh.

Artist: William Dodd - Chatham Dockyard (1789)

The custom and practice of his Majesty's bakehouse at the port of Chatham, with the manner how the service is carried on therein, viz.

1. The meal received into store from London is weighed and when dressed or bolted is delivered by weight to the bakehouse as occasion requires, and that with the produce of the bran, which is generally two bushels and half from a quarter [eight bushels] of meal, makes out the quantity first received.

2. The produce of one quarter and half of meal being 672 pounds is: biscuit, 638 pounds; and the same quantity in loaf bread makes 422 in number, or 844 pounds, each loaf being 2 pounds.

3. The biscuit as it is drawn from the oven is shot loose in a storeroom from whence it is weighed into bags, and the loaf bread is weighed singly before baked at 34 ounces so that when they come out of the oven each loaf weighs two pounds avoirdupois . …

5. There are three ovens, two for biscuit and one for bread; and to raise the great oven, which carries upwards of one hundredweight, it requires 30 bavins [bundles] the first sute [group], and 8 each sute afterwards; to raise the middle oven which carries about 1 of a hundred, 20 bavins the first sute and 5 afterwards; and to raise the small oven, which carries about 120 petty warrant loaves, 8 bavins each heating.But having now only four bakers besides the furner [baker in charge] we make use of the great oven by itself only for biscuit and the other two for bread.8

Note that this mentions yet another period navy baking location: Chatham. The navy had had a presence at Chatham beginning in the early 16th century. By the beginning of the War of Spanish Succession (1701), they had a slaughterhouse and a small bakery there, although it was no where near large enough to supply the navy at that time.9 This outline specifically mentions the navy sifting ('bolting') their own flour and producing bran as a result. Unfortunately, it doesn't mention what is done with the bran. It also says the biscuit was put into bags after coming out of the oven. Whether these bags of biscuit were placed in a dry, warm loft can't

Photo: Paul A. Cziko - Ship's Biscuit from the Kronenberg (1752)

be determined. The final item of interest here is how much of the bread they were producing was fresh, loaf bread, specifically identified as 'petty warrant loaves' served when a ship was in port.

Curiously, none of the naval sailors' accounts included here specifically mention biscuit, even though we know it was a staple of their meal plan and they all ate it. Navy biscuit is described by French traveler César de Saussure who was aboard HMS Torrington in 1729, a few years after the end of the golden age or piracy. "These biscuits are as large as a plate, white, and so hard that those sailors who have no teeth, or bad ones, must crush them or soften them with water. I found them, however, very much to my taste, and they reminded me of nuts. All the time we were at sea we had no other bread."10

Although he doesn't specifically state it, de Saussure implies that they are round like a dinner plate. English naval physician William Cockburn described the daily allowance of bread in his 1696 book as "a pound of bread so dry and solid as that must be, that it may be the fitter for keeping, if it were brought to the consistence of common bread, would at least be thrice as big as it is, while in Bisket; which, I'm apt to believe, is a little too much for men generally to eat."11 As Cockburn indicates, the navy allowed every sailor a pound of biscuit daily, which dates back to at least the 1636 victualling contract and is reiterated in the 1677 victualling contract, the 1701 letter from the Admiralty to the Navy Board and the 1731 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea.12

In addition to being supplied at sea by the navy, biscuit was purchased for most merchant, buccaneer and privateer voyages and either bought or stolen by pirates. There are 9 instances in the sailors accounts which specifically

Artist: Theodor de Bry

Sailors Loading Supplies From Pizarro and Pedro de Almagro swear an oath, America, pt 6 (1597)

mention it.13 Most of them only mention it. One exception comes from Father Jean-Baptiste Labat's voyage aboard the barque Aventurierre in 1701. It had been captured by the Spanish, only to be released upon learning that the French and Spanish had become allies. (News traveled relatively slowly at this time.) When the Spanish left the Aventurierre, they sent Labat a number of items including "a barrel of white biscuits"14. The other description of interest comes from buccaneer Ravaneau de Lussan's account of the capture of Nicoya, Costa Rica in 1687. The buccaneers threatened the governor, "if he did not send us so many horse-load of biscuit and mace [nutmeg], as we required of him for the ransom of the town, he might assure himself we should go and burn it."15 In addition to specific mentions of biscuit, there are additional 11 instances which refer only to bread on long-distance voyages that most likely refer to biscuit, two of which happen to be from accounts of English naval ships.16

1 J. R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 166; 2 "Any GRAIN such as BARLEY, OATS, RYE, WHEAT, but probably not RICE, nor the so-called INDIAN CORN that only became commercially available towards the end of this period [early 1800s] in Britain." ("Corn", Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1520-1820, british-history.ac.uk, gathered 11/3/22); 3 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 304; 4 "When biscuits were baked twice", grammarphobia.com, gathered 3/13/23; 5 Paula K. Watson, The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714, University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 83; 6 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 303; 7 Benjamin Franklin, A Letter from Dr. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, to Mr. ALPHONSUS le Roy, Member of several Academies, at Paris. Containing sundry Maritime Observations", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 1786, Vol. 2, p. 322; 8 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration 1715-1750, 1977, p. 411; 9 Watson, p. 92; 10 César De Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 363-4;11 William Cockburn, An account of the nature, causes, symptoms, and cure of the distempers that are incident to seafaring people, 1696, p. 22; 12 CSP Domestic, 1636-7, 1867, p. 452; J. R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 165; Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 254; Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 61;13 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 194; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 128; Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 88 & 89; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 76; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 297; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 197; Ravaneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 402; Silas Told, An Account of the Life, and Dealings of God with Silas Told &c., 1786, p. 14-5; 14 Labat, p. 197; 15 de Lussan, p. 402; 16 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol. 1, 1712, p. 324; Cooke,Vol. 2, 1712, p. 60; “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 23; “22. David Herriot and Ignatius Pell on Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet, from The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and other Pirates (London, 1719), pp. 44-48”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 99; “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, Ed Fox, cd., p. 255; Captain Edward Wright, “Successful Defense of the Caesar, 31st October 1680”, The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., November 1919, p. 205; William Soame, “Letter from William Soame to the Honble Nath Higginson Esq. and Council at Fort St. George, dated Achin 11 August 1697”, The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., Volume XLIX, January, 1920, p. 3; Stephen Martin-Leake, The Life of Sir John Leake, 1920, p. 222; "Pyrates Lately taken by Captain OGLE", 1723, p. iv; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 207; Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, 1825, 1825, p. 200;

Rusk

The final type of bread found in sailor's account is rusk. This is twice-baked bread. Usually, we can depend on period authors to be rather loose in their terminology and it is quite possible that some of the instances of biscuit may have actually been rusk or vice-versa. However, we find some distinction being made regarding these two similar breads, even by sailors, perhaps because it was important to them. Edward Cooke,

Photo: Rik Andreae - Modern Rusk or Dutch Beschuitje

then captain of the Dutchess, the smaller of Woodes Rogers' privateer fleet, recorded the minutes of a meeting held in 1710 where it was decided that each ship's officers might have "Butter, sweet Oil, Bread or Rusk, Flower, Tamarinds, Spelmans Neap, Cheese, Cape-Wine, and some Spanish Money, to buy small Necessaries."1 What bread refers to here may either be biscuit or loaf bread. (Cooke never uses the word 'biscuit' in his books, only referring to 'bread'.) While officers would have had better food, loaf bread didn't last very long at sea when the privateers were in enemy territory, so it is not a stretch to suggest he is referring to biscuit. More to the point, historian Peter Earle cites the records of the merchant ship Vinor Frigott which travelled the Mediterranean from 1676-8, noting that at Alexandra, Egypt "'Rusk' ...as well as biscuit were purchased for 'sea store' when the ship set off back to Leghorn [Livorno, Italy]"2. Privateer George Shelvocke talks about all three kinds of bread in his book, mentioning that while his ship Speedwell traveling around Chile in the Spring of 1720, the men had "3 ounces of very good rusk to breakfast every morning"3. Two months later, the Speedwell wrecked on Juan Fernandez, where Shelvocke says he saved "about 7 or 8 bags of bread" from the bread room (a dry room where biscuit is kept to protect it on navy vessels).4 Five months after that, he mentions stealing both rusk and "soft" or loaf bread from Inuique, Chile.5

The difference between rusk and ship's biscuit is mentioned well before this period. During a journey from England to North America, John Josselyn, who had a medical background, reported that the common sea victuals for sailors during his journey in 1638 consisted of "Beef, or Porke, Fish, Butter, Cheese, Pease, Pottage [oatmeal], Water-Gruel, Bisket and six shilling Bear [low alcohol beer]." He apparently didn't think much of this because he recommended readers making the

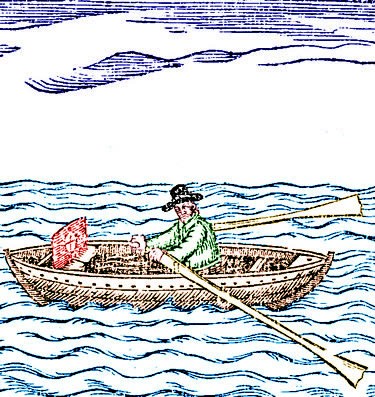

The Sculler, By Waterpoet John Taylor (1612)

same journey should bring 'private fresh provision' which included "White Bisket, or Spanish rusk"6. The connection between the Spanish and rusk is an old one, likely referring to their use of twice-baked bread at sea. When poet and waterman John Taylor wrote about his 'armada' of ferrymen in 1627, he explained that the bread they used "was not rusk as the Spaniards use, or oaten-cakes, or bannocks [a type of flat bread], as in North Britain, nor biscuit as Englishmen eat, but it was bread they called Cheat-bread... so called because the baker was never paid for it."7 Although tongue-in-cheek, this clearly differentiates twice-baked rusk from English once baked and then extensively dried biscuit.

Naturally, most sailors only mention rusk without providing a description. The one sailor who does take any time to describe it is William Dampier, who says that when the buccaneer vessel Cygnet stopped at Guam in 1686, the governor of the island sent them "a Jar of fine Rusk, or Bread of fine Wheat-Flower, baked like Bisket, but not so hard."8 Here we have both a distinct differentiation between biscuit and rusk, a comparison of the two and a mention of its composition.

The last comprehensive explanation of rusk and differentiation of it from biscuit, comes from Ben Franklin's 1775 letter to Alphonsus le Roy. "But rusk is better [than English biscuit]; for being made of good fermented bread, sliced and baked a second time, the pieces imbibe the water easily, soften immediately, digest more kindly and are therefore more wholsome than the unfermented biscuit. By the way, rusk is the true original biscuit, so prepared to keep for sea, biscuit in French signifying twice baked."9 By 'fermented' bread, Franklin is referring to bread made with yeast, which English sea biscuit was not.

1 Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol., 2, 1712, p. 60; 2 Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 89; 3 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 203; 4 Shelvocke, p. 207; 5 Shelvocke, p. 268; 6 John Josselyn, Account of Two Voyages to New-England, 1674, p. 13; 7 John Taylor, An Armado, Or Navye, of 103 Ships, 1627, p. 6; 8 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 303; 9 Benjamin Franklin, A Letter from Dr. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, to Mr. ALPHONSUS le Roy, Member of several Academies, at Paris. Containing sundry Maritime Observations", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 1786, Vol. 2, p. 322

Bread as Food

Bread from the finest flour, Tacuinum Sanitatus, f. 61r, (15th c.)

As food, the period comments focus on loaf bread, which was thought to be the healthiest. Botanist Louis Lémery advises, "The best is that made of good Wheat Flower, wherein they leave a little Bran, which is well kneaded, and sufficiently fermented, and lastly, well baked, with a moderate heat, so that it ought not to be neither too hard, nor too soft."1 Vegetarian Thomas Tryon declared, "Bread hath the first place of all Food, and may justly be call'd Concord, or a thing which God and his Hand made; Nature hath befriended with all the united good Vertues, both of the Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms, and therefore no sort of Food is comparabIe"2.

Tryon provides a description of the making of loaf wheat bread, explaining that the best is leavened (with yeast), light, "being well kneaded and throughly bak'd, for the good working of Bread does not only make it pleasant to the Pallat, but also renders it easier of Concoction [digestion, referring its conversion into chyle in preparation for forming bodily humors], smooth and free from crumbling"3. It is then left to lie for an hour or two and made into loaves. He warns that when baking it, "care must be taken that your Oven be not too hot, nor your Fire too quick, but it should be heated gradually... or else your Bread will not only be scorch'd and burn'd on the out-side, but will be also unbak'd in the in-side"4.

Physician William Salmon gives a more concise description of how barley loaf bread is made.

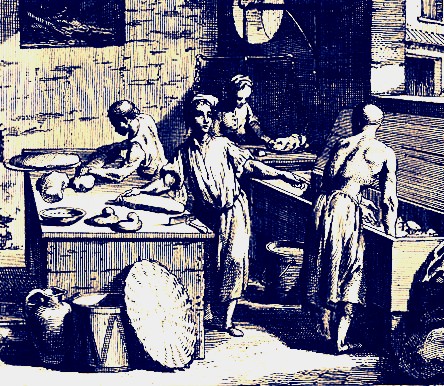

Boulanger (Baker), From Encyclopedie, By Denis Diderot (1765)

It is made of the Flower with a proportional quantity of Water and Salt; to every bushel of which Flower, a sour Leaven, as big as a Mans fist doubled, or a Pint of Ale Yest, is added, being dissolved in the warm Water, with which the Paste or Dough is made: this being mixed with one part of the Flower, is covered with the other, and left in digestion for an hour or two, that the whole may be Leavened, then the Paste or Dough is made by mingling all well together, and kneading it with the hands, till it becomes a stiff Paste; which then is Suffered to ly again about half an hour, and then made up into Loaves, which are after baked in an Oven.5

Several of Salmon's steps are mentioned by Tryon in his explanation of how the best loaf wheat bread was made. Lémery lists the same steps, focusing a bit more than Salmon on details like the type of leaven used, mixing the ingredients well, the temperature of the water poured on the flour.6 Most grain breads are made similarly. Note that the yeast was brewer's yeast, which was typically what was used to leaven bread at this time.

Thomas Tryon does have something to say about biscuit as food. He advises, "tis well known, that Bread which is designed to be kept for a considerable while, must have neither Salt, Ferment nor Yeast in it; and this sort of Bread which is generally made for Sea, is some of the sweetest."7 Being something of a food activist, Tryon was unlike several other authors not being a fan of additives to breads.

1 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 68; 2 Thomas Tryon, The way to health and long life, 1697, p. 46; 3 Tryon, The way to health..., p. 135; 4 Tryon, p. 136; 5 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 1, p. 62; 6 Lémery, p. 71; 7 Thomas Tryon, Tryons Letters Domestick and Foreign, 1700, p. 237;

Humoral Qualities of Breads

Discussing the humoral qualities of bread is a bit more

Ibn Butlan and two Students, From Codex Tacuinum Sanitatis (c. 1390)

complex than most other foods presented here because some of the ancient authors felt that different types of bread had different qualities. The 15th century Tecuinum Sanitatis ('Maintenance of Health') was based on a book by 11th century Arabic physician Ibn Butlan. Like many scholarly works which present humoral information, Ibn Butlan's work is built upon the books of Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscoredes.1 Its division of breads is similar in some ways to the way the English divided penny breads.

Bread made from the finest wheat flour was judged by Ibn Butlan to be "moderately hot in the second degree" and good "for temperate [temperaments], for all ages, in all regions, at any time."2 Unleavened bread, almost certainly wheat-based, would include navy biscuit. Ibn Butlan considered it moderately dry in the second degree like fine wheat bread, producing "much thick phlegm" being good for "hot [temperaments], those who take exercise, youth, in winter and in cold regions."3 Tryon said that wheat bread engendered the best blood, one of the four bodily humors.4 Brown bread, made from lesser wheat flour with other grain flours possibly being mixed in was simply "hot in the second degree"5 according to the Tecuinum, indicating its impact on the humors was more intense than the 'moderately' hot bread. It was also good for all temperaments. In the early seventeenth century, physician Thomas Cogan said that the 'ill effects' of wheat could be offset by proper baking and salting, "for bread [which is] over sweet is a stopper [caused constipation]; and bread over-salt[ed] is a drier."6 He said that stale or moldy bread was similarly drying and burnt bread would "engender adust choler [the humor

Rembert Dodoens (1517–1585)

yellow bile, burnt], and melancholy [black bile] humours"7. Louis Lémery, providing the Paracelsian perspective, says that "Bread contains much volatile Salt, Oil, and Phlegm. Bread agrees at all times with any Age and any kind of Constitution."8 He implies that he means wheat bread with some bran mixed in here.

The humors found in some other types of bread are mentioned by some of the authors from the period. Botanist John Gerard says that barley bread had "a certain force to coole and dry in the first degree, according to Galen in his booke of the Faculties of Simples. It hath also a little abstersive or clensing qualitie"9. Lémery suggests that corn [maize] bread "contains much Oil and essential Salt"10. Tryon cites sixteenth century Flemish physician Rembert Dodoens as indicating that rye bread is hot and dry in the second degree.11 According to Ibn Bhutan, millet bread, made from pearl millet, was cold and dry in the second degree. It produced "moderate melancholy and heavy humour[s]."12

1 Loren D. Mendelsohn, "The Tacuinum Sanitatis: a Medieval Health Manual", CUNY Academic Works, 2013, p. 71; 2 Tecuinum Sanitatis, 15th century, f. 61r; 3 Tecuinum Sanitatis, f. 62.r; 4 Thomas Tryon, The way to health and long life, 1697, p. 46; 5 Tecuinum Sanitatis, f. 61.v; 6 Thomas Cogan, Haven of Health, 1636, p. 25; 7 Cogan, p. 27; 8 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 70; 9 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 71; 10 Lémery, p. 68; 51 Tryon, The way to health..., p. 29; 12 Tecuinum Sanitatis, f. 62.v

Medicinal Properties of Bread

Different breads were said to have different medicinal properties.

Artist: Job Berckheyde - The Baker (c.1681)

Not surprisingly, much attention was paid to the effects of loaf wheat bread. The Tecuinum Sanitatis indicated that the primary benefit of fine white wheat bread was to 'fatten the body" while its primary detriment was that it caused obstructions, something that could be combatted by adding yeast.1 French botanist Louis Lémery identified the problem with wheat bread was when it was "eaten too new, because it will clog the Stomach, but you ought rather to stay [wait] 'till it is a little stalish." He said that toasted wheat bread crumbs were "binding, but the Crumb[s] used in Cataplasms, softens, digests, sweetens, and dissolves."2 Naval physician William Cockburn explained that 'moderate eating of bread' helped slow the movement of food through the digestive system, without which the chyle created during digestion (the first step toward transforming food into humors) lacked the 'necessary body' to move properly through the body resulting in "gripings [sharp pain in the bowels], most troublesome loosenesses [diarrhea], and such other sicknesses." However, he also warned that overeating bread was bad because it was "not so easily broken and divided by the stomach, and if eaten at any time in a greater quantity than is sufficient to give a body to the Chyle, it is very apt to make way for obstructions, and to breed very thick and gross humours."3 Physician William Salmon advised that wheat bread was "good against Weaknesses and Fluxes of the Bowels, and if made with Milk and Eggs, strengthens much, and restore in deep Consumptions, being also very easie of Digestion:"4

Artist: Jean Michelin - Peasant Bread, The Baker's Cart (1656)

Cockburn advised leavening bread as well as adding some bran to the dough, explaining that this "makes the Bread more porous, and easier to be attenuated by the fermentation of the Stomach."5 In a similar vein, doctor Clifton Wintringham recommended tempering wheat bread's costiveness with the addition of "a small Portion of Rie [grain] or Bran mix"d with it."6 Recall Louis Lémery's recommendation that a little bran should be added to even the best sifted wheat flour.

According to the Tecuinum Sanitatis, brown wheat bread, that made of unsifted flour and containing more bran, "moved the bowels" although "it causes itching and scabies", something that could be remedied with 'fatty foods."7 Thomas Cogan was much more severe, criticizing brown bread as filling "the belly with excrements, and shortly descendeth from the stomacke". However, he also adds "that it is good for labourers… [and] I have knowne this experience of it, that such as have beene used to fine bread, when they have beene costive [constipated], by eating browne bread and butter, have beene made soluble."8

The Tecuinum Sanitatis indicates that unleavened wheat bread (which biscuit would be made from) was recommended "for untoned and exercised bodies"

Artist: Floris Gerritsz van Schooten

Still-Life with Glass, Cheese and Biscuits (1st half of the 17th century)

, but "it causes bloating, flatulence and obstructions", the remedy for which was "good, mature wine"9. Cogan cited Galen as indicating that "all kinde of bread made without leaven is unwholsome, and ...descendeth slowly from the stomack engendreth ...oppilations [obstructions] of the liver, increaseth the weaknesse of the spleene, and breedeth the stone in the reines [kidneys]."10 With the exception of kidney stones, these are references to humor theory which held that the liver was key to converting food into humors and the spleen produced yellow bile. Naval physician Cockburn suggested that when biscuit reached the stomach, "'tis extremely hard, to be digested, if it be not very fine, ...is so hardned and compact, that people upon that diet but seldom trouble the Stool; which every one knows to be of very ill consequence, and especially at Sea."11 He goes on in his discussion of biscuit to suggest that the sailor's diet resulted in the "grossness of their humours, [from which] Seamen are dispos'd to most Chronical Diseases, so soon as they are in the least overcome with idleness and Iaziness: tho, otherwise, all the inconveniencies that happen, are excessive costiveness, that troublesom attendant of our sicknesses."12 Cockburn later wrote a whole book on troubles of the bowels.

Barley loaf bread was nowhere near as popular in England as other bread types, but William Salmon discusses its medical properties. He recommends eating it soon after baking, it "agreeing then most with the Stomach, and nourishing best. Apply'd to the place where the Pain is, in a Vehe[ment] Head-ach, as soon as it comes out of the Oven, or as hot as the Patient can indure it, it gives present

Photo: Douglas Perkins - Cornbread/Journeycake/Johnnycake

ease; and in a few times Application, cures it."13 (He says something very similar about rye bread.) Lémery also mentions barley bread, although he doesn't recommend it, only noting that it is "not so nourishing as that of Wheat or Rie".14

Salmon comments on cornbread, although his references to its medicinal value are limited. "This Bread whilst New, is wonderful Sweet, beyond any that can be made of European Wheat; but being Stale, it eats something harsh, and more unpleasing; After one is used to it, it is then Eaten with a Gratefulness to the Stomach."15 Lémery notes that cornbread "is hard of Digestion, heavy in the Stomach, and does not agree with any but such as are of a robust and hail Constitution."16

The Tecuinum Sanitatis says that [pearl] millet bread "nourishes and tones the intestines", but is "difficult to evacuate", which can be tempered "with exercise, baths and [eating] fatty things."17 Salmon suggests that "it restores in Consumptions, and Strengthens the Stomach and belly."18 Lémery ruled that millet breads, along with those made from spelt and rice, "are hard of Digestion, and are not by a great deal so well tasted as our ordinary Bread."19

Oat bread, according to physician Thomas Cogan, "is light of digestion, but something Windie, while it is new it is meetly

Photo: Ken Eckert - Rye Bread Loaves

[eats] pleasant; but after a few dayes it waxeth drie and unsavorie it is not very agreeable for such as have not been brought up therewith"20. Salmon says it stops "Fluxes of the Bowels, nourish[es] much, and restore[s] in Consumptions"21. Even Lémery indicated oat bread "is Nourishing enough, and serves them [who eat it] very well."22

Last is rye bread, which Cogan says "is not so wholesome as wheate bread, for it is heavy and hard to digest, and therefore most meet [best as food] for labourers, and such as worke or travaile much, and for such as have good stomacks."23 (This is a fairly common opinion about the majority of the non-wheat breads, hinting that it was food for the working poor.) Salmon states, "It nourishes much, and is Stomatick, yet apt to Gripe [give stomach pains to] some People. Applied hot as can be endured out of the Oven, to the most Vehement Head-ach, and left on till it is cold, it presently eases the pain... if repeated some few times it perfectly cures it. And so applied to the Stomach it helps the weakness thereof, and the Palpitation of the Heart."24 Lémery notes that people mix it with wheat to improve the flavor of that bread. However, rye bread alone is "not so nourishing as Wheat Bread, and is a little Laxative.”25

1 Tecuinum Sanitatis, 15th century, f. 61r; 2 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 68; 3 William Cockburn, An account of the nature, causes, symptoms, and cure of the distempers that are incident to seafaring people, 1696, p. 20-1; 4 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 1251; 5 Lémery, p. 70; 6 Clifton Wintringham, A Treatise of Endemic Diseases, 1718, p. 99; 7 Tecuinum Sanitatis, f. 61.v; 8 Cogan, p. 27; 9 Tecuinum Sanitatis, f. 62.r; 10 Cogan, p. 24; 11 Cockburn, p. 22; 12 Cockburn, p. 23; 13 Salmon, Book 1, p. 62; 14 Lémery, p. 70; 15 Salmon, Book 2, p. 1254; 16 Lémery, p. 70; 17 Tecuinum Sanitatis, f. 62v; 18 Salmon, Book 2, p. 714; 19 Lémery, p. 71; 20 Cogan, p. 30; 21 Salmon, Book 2, p. 787; 22 Lémery, p. 70-1; 23 Cogan, p. 29; 24 Salmon, Book 2, p. 945; 25 Lémery, p. 70 .

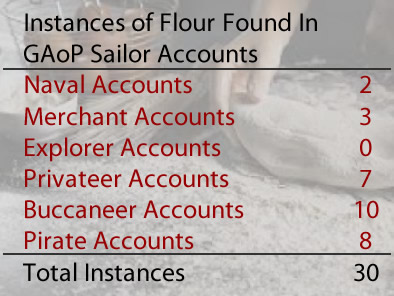

Flour

Called by Sailors: Dough-Boys, Doughboys, Farine, Flour, Flower, Puddings, Wheat-Flower

Appearance: 30 Times, in 19 Unique Ship Journeys from 19 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Livorno, Italy; Crete, Greece; Bab-el-Mandeb; Mussendon, Oman; Buru, Jakarta, Indonesia; Providence, Bahamas; Cuba; St. Croix; Ixtapa, One Bush Key & Zihuatanejo, Mexico; Salvador, Brazil; Chileo Island, Chile; Lobos de Tierra, Peru; Cerro Hoya Mountain & Diafara, Panama; Cabo Blanco & Cocos Island, Costa Rica; Isla del Tigre & Roatán, Honduras; Massachusetts & Rhode Island, North America;

As explained the first page of this article, flour was ground in stone mills, with the best flour being ground several times and strained through cloth screens to remove the bran and germ of the grain,

, Etwas für Alle, by Father Abraham à Santa Clara, Christoph Weigel, 1699.jpg)

Artist: Christoph Weigel

Der Müller (The Miller), From Etwas für Alle, by Father Abraham à Santa Clara (1699)

which produced the finest, whitest flour. The less preferred, darker flours were only ground once, leaving in most of the bran and wheat germ. The navy specification for flour purchased to make bread was for "good, clean, sweet, sound, well bolted with a horse cloth" wheat flour.2 If the contractors did not cheat them by supplying inferior flour, the navy was using the 'best' wheat flour available. East India Trading Company ships would have purchased similar flours. For other long-haul sailing vessels, it is nearly impossible to say what sort of food they might purchase unless it is specified. However, it is likely that the flour purchased for most ships leaving England was wheat flour. Once a ship reached a foreign port, even the navy had to buy whatever was available to them if they had not set up a foreign agent to make sure wheat flour was on hand. Wheat did not grow as well in African, Middle Eastern and southern New World locations. Because of this, rather than counting all non-specific flours as wheat, this article errs on the side of caution and counts them separately. Instances of flour which specify the grain they are made from are not counted here but with the relevant grain. (These include one instance of barley flour3 and two of wheat flour4.)

Flour is well supported in the sailor accounts as the above numbers indicate. It is also well supported in the pirate accounts. When pirate Christopher Goffe was sailing off Providence, Bahamas in 1687, Jamaican Lieutenant Governor Hender Molesworth wrote to the secretary of the Privy Council's committee on trade and foreign plantations (William Blathwayt): "It is said that some of these pirates have at times given half a crown a pound for flour."5

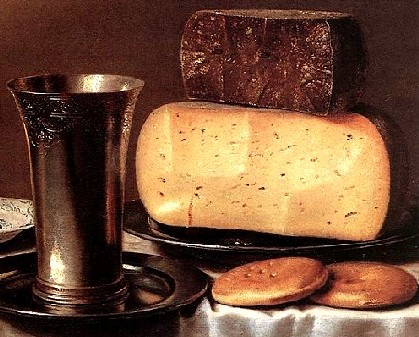

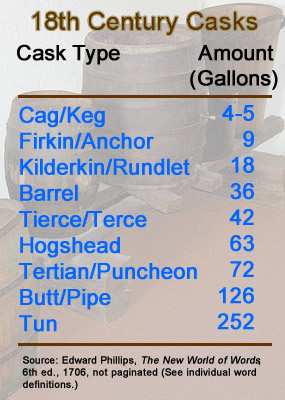

Flour had to be kept dry, so it was stored in casks on a ship. The 1677 Navy victualling contract specified that "flour casks are to be 'wind and water

Image Artist: Georges Jansoon

Traditional 18th Century Cask Sizes

tight'"6 to prevent spoilage. Several pirate accounts mention flour being stored in casks of various sizes. Pirate Thomas Pound captured the brigantine Merrimac off of Martha's Vineyard in 1689 where "the vessel was plundered of twenty half-barrels of flour, and sugar, rum and tobacco."7 Henry Every was given two barrels of flour by another pirate vessel while they waited off 'Babs Key' (Babel-el-Mandeb) for they Mocha fleet in 1693-4. Stede Bonnet took "several Barrels of Pork and Flower, and other Provisions" from a sloop captured in Cape Fear River in 1718.8 When Edward Low captured John Hance's vessel in June of 1722, he "took almost all the Bread and Flower he had" which amounted to "a Tun or two of Flower".9

Sometimes flour was stolen from land-based sites where it didn't necessarily have to be stored in well sealed casks. Buccaneer accounts of Bartholomew Sharp's ship Trinity mention that they had taken 1200 "packs" of flour from modern Naos, Panama in 1680 and still had some of it aboard in September of that year when they took a ship near Cabo Blanco, Costa Rica to whom they gave all their Spanish prisoners along with six packs of flour.10 Dampier repeatedly refers to procuring 'packs of Flower' in his first book when the buccaneer vessel Cygnet was sailing off the western coast of Central America in 1684 and 1685.11 When thirty men from the privateer St. George landed in Zihuatanejo, Mexico in November of 1704, they "found a great many small things, with 16 Packs of very good Flower."12 The word 'pack' in these instances refers to bags of flour, probably made of canvas or some similar material. The sizes of the bags cannot be discerned from these accounts.

As food, flour makes most people today think of making bread, pies, cakes and such, but even the largest navy ships during this period were ill equipped to bake effectively. (This isn't to say that it could never have happened, just that it would be extremely unlikely on a regular ship, let alone a pirate vessel.) The person most likely to bake shipboard, would have been the cook assigned to the officers on a naval vessel or and East Indiaman. Ordinary ship's cooks were not trained to do much more than boil food. As a result, the use of flour at sea was primarily boiled to make things like puddings and doughboys.

Although not specifically mentioned in the navy menu, puddings were implied. The 1677 English navy victualling contract included flour as an alternative food, stating that "in lieu of a piece of beef or

A Pudding Bag

pork with pease, three pounds of flour and a pound of raisins (not worse than Malaga), or in lieu of raisins, half a pound of currants or half a pound of beef suet pickled"13 could be given to a sailor. The flour was meant to be combined with the raisins/currents or with the beef suet in a pudding bag and then boiled to make simple plum or suet pudding. This was reiterated without changes in a letter from the Admiralty to the navy in 170114, although "the substitution of flour, raisins, and suet for beef or pork was no more popular with the seamen than was the' beverage' (country wine mixed with water) instead of beer."15 In 1703, the Victualling Board wrote the Admiralty about providing fresh victualling to ships in port because of a perceived unhealthiness in eating an excess of salt meat. They noted that "even on those two days [where salt beef was served, the sailors] are sometimes relieved by flour and suet for pudding in lieu of beef."16 Note that raisins and currants are left out; this suggests that the primary use of flour at this point was to make suet pudding. This is repeated by French traveler César de Saussure, who was aboard HMS Torrington in 1729. He explained that the sailors' regular diet three days a week included, "a pudding made of flour and suet."17. Such puddings also appeared on non-Navy ships. The captain of the merchant ship Adventure reported that before a mutiny caused by future pirate captain Joseph Bradish in 1698, "on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays they [the sailors] had [at] every Mess a piece of good Beef and a Pudding of two pound and a half of Flower with ¼ of Suet"20.

In addition to the above two savory puddings, there were also sweet puddings; sometimes generically

Photo: Lachlan Hardy - A Bag Made Plum Pudding

called plum puddings, although they could be made with any fruit. Navy clerk John Baldridge actually refers to 'plum-pottage' in his poem, although he uses the term poetically rather than literally. He does talk about a celebratory pudding made for Christmas in 1670: "With Puddings mixt with Fruit and Oyl, In furnace this same day we boyl: Our Gunners Pudding made so great, That twenty men could scarce it eat"21. Naval chaplain Henry Teonge also mentioned the officers of the HMS Assistance enjoying 'plumb puddings' on Christmas day of 167522, although it is not counted here because these articles focus on food for the regular, before mast men rather than the officers. Neither of these two accounts mention the ingredients of fruit pudding. There is a period recipe for plum pudding in Maria Ketelby's 1714 cookbook which would be mostly appropriate for regular shipboard fare. "Take one pound of Suet, sliced very small and sifted, one pound of Raisons ston'd [pit removed], four spoonfuls of Flower, and four spoonfuls of Sugar, five Eggs, but three Whites; beat the Eggs with a little Salt: Tie it up close [in a pudding bag], and boil it four Hours at least."23 With the exception of the eggs, everything mentioned could be found in the ship's stores.

Traditional Dough Dumplings

The other food which can be made from boiled flour are doughboys. They appear 3 times in the sailors accounts.24 Henry Watson, a prisoner of pirate John Hoar, explained that while the pirates were careening their ship on an island near Cape Mussington (modern Mussendon, Oman), they "killed great quantities of antelopes, until being weary of that kind of flesh and having nothing but stinking beef and doughboys (that is dough made into a lump and boiled) they weighed anchor"25. William Dampier, who was even more strapped for food when his Jamaican barque was blown off course near Cuba, complained, "our Flour almost spent, we cut our Beef in small bits after 'twas boiled, and boiled it again in Water, thickned with a little Flour, and so eat it altogether with Spoons. The ...Bread and Flour being scarce with us, we could not make Dough-boys to eat with it."26 So doughboys were essentially dumplings made from flour and/or bread with some water to hold them together which were then boiled.

Most of the period botanists and physicians have little to say about the flour or 'meal' of cereal grains from a humoral standpoint. Physician William Salmon talks more about the varieties of flour (or 'meal') which come from cereal grains than other authors, specifically discussing barley, millet, oat, rye and wheat flours. Since the flours are just the grains processed so they are edible, possibly having some of the bran and grain removed,

Photo: Pexels Contributor diosix - Wheat Flour

the humoral properties would be the same as the grains. One author who mentions the humoral qualities of two flours is sea surgeon and John Woodall. He includes both wheat flour and barley flour in his list of medicines to be brought to sea in the East India Company's surgeons chests. He says wheat flour is hot in the first degree and barley flour is cold and dry in the first degree.27 These are the same humoral properties as the raw grains.

Physician Salmon talks specifically about the medicinal properties of some of the cereal grain flours. Perhaps the most enlightening thing he says about them concerns cataplasms or poultices. "They are made with Oil or Fats, adding the boiled Pulps of Roots, or Figs, and the other proper Ingredients according to the Intention... bringing it to a due Consistency with Flower of Oatmeal, Barley-Flower, Orobus-Meal [made from vetches], Crumbs of White [wheat] Bread, Milks, &c. boiling all to a due softness."28 The use of flour in cataplasms is repeated by the other medical authors from the period.

Sea surgeon John Woodall felt that barley flour would "dissolveth

Photo: Forest and Kim Starr - Purple and Bronze Hand-Ground Barley Flour

hot and colde tumours, digesteth, softneth, and ripeth hard swellings, stoppeth the laske [looseness of the bowels], and humors falling into the joints, discusseth winde is good against the scurfe [flaking of the skin], and leprosie, and allaieth the inflammations of the Goutes."29 Botanist John Gerard adds to Woodall's list, recommending barley cataplasms combined with various other ingredients to treat gout, joint pain, tumors of the 'privy parts', dropsy [edema], sciatica, swellings, inflammations, carbuncles, a stuffy head, St. Anthony's Fire [a type of herpes], fretting ulcers, scalding, burning, leprosy, tetters [red, irritated skin], pushes [pimples], eating ulcers, 'fiery heat of the eyes', mad dog bites and warts.30

Salmon says that millet flour could be "Made into Bread or Cakes, or Puddings, and eaten, it restores in Consumptions, and Strengthens the Stomach and belly."31

Since oatmeal was readily available on most ships, it is used to make cataplasms by sea surgeons, who may have

Whole Grain Oat Flour

ground the dry oats in a mortar to create oat flour or simply used already cooked oatmeal. Talking about gunshot wound treatment, sea surgeon John Atkins advised using oatmeal-based cataplasms since they were in "no way inconvenient in the·Navy, where

a Copper-Full of Oatmeal is boiled three Times a Week, ([being] as good for Use as any)"32 Sea surgeon Woodall suggested oat-based cataplasms to relieve pain from wounds near the joints and the restoration of dislocated bones.33 As mentioned in the section on oats, botanist Gerard also recommended using oatmeal as a cataplasm because it "dries and moderately discusses, and that without biting [causing pain]; for it hath sornewhat a coole temper, with some astriction [ability to stop bleeding and close wounds], so that it is good against scourings [inflammation]."34 Physician Salmon advised using oat flour to make bread and cakes which would "stop Fluxes of the Bowels, nourish much, and restore in Consumptions [tuberculosis]." However, he also warned that "Puddings made of the Oat-Meal, whether whole or Ground and filled very full with Beef Suet shred small, and blew Currants, or Raisons of the Sun, always loosen the Belly."35

Salmon said that rye flour "is more forcible than Wheat, in wasting and consuming Tumors, and clammy Humors; yet made in Broth, or Puddings, and Cakes, it gives good Nourishment." As

Whole Grain Rye Flour

with other flours, he suggests using it as a cataplasm, where it "strengthens the Nerves and Joints, over-strained, or lately put out of place: it discusses Tumors, and eases Pains, and prevails against an Oedema [swelling of the body's tissues], an Erysipelas [acute skin infection], and the Gout. And bound unto the Head in a Linnen Cloth, it eases a Cephalea, or long continued Head-ach, and the Megrim."36 Gerard likewise recommends using rye meal in linen cloths to treat long-lasting headaches.37 Sea surgeon John Moyle describes a cataplasm of Rye as one of his 'most approved

Remedies now in Use for

the Cure of most Distempers incident

to Humane Bodies by Sea

or Land'. "Take Rye Flower, Pigeons Dung, of

each one Ounce, Vinegar enough to make

it into a Pultice, spread it on a Linnen Clout [cloth], and sprinkle a little white Vitriol on it. It wonderfully stops a Herpes."38 Although pigeon dung would have been available when a ship was near land, rye is not among the grains, meals or flours normally found on naval ships, so it is unlikely that this cataplasm was meant for use at sea.

Wheat flour was found aboard most ships, so it had support from some of the sea surgeons. Woodall gives it a glowing recommendation, stating that it "stoppeth spitting of bloud, distillations of subtill humours, helpeth the cough, roughnesse of the sharpe arterie, dissolveth tumours, and cleanseth the face from lentils and spots, appeaseth hunger and thirst, and is the

Whole Grain Wheat Flour

principall naturall upholder of the life and health of man."39 He also recommends a cataplasm of "Wheate meale boyled with water and vinegar a Convenient quantity that it bee not over sharpe, adding a little Terebinthine [turpentine]" to repel an abcess.40 When removing a pipe (cannula) that caused excessive bleeding when inserted, sea surgeon Atkins recommends "Compresses spread (to restrain it) with Wheaten Meal beat up with the Whites of Eggs."41

Several authors comment on the healthiness of wheat as food. Thomas Tryon declares, "Milk ...mixt with [wheat] Flour, does make some of the most healthy and wholsomest Food that can be eaten for all sorts of People and Ages”42. Physician Salmon says of boiled wheat flour puddings, "They have the Virtues of Bread, are good against Weaknesses and Fluxes of the Bowels, and if made with Milk and Eggs, strengthen much, and restore in deep Consumptions, being also very easie of Digestion"43.

1 "The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Capt. John Quelch", A Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol. 14, 1700-1708, 1825, p. 1082; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 73; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 194; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 60; Ambrose Cowley, A Collection of original voyages, William Hack, Ed., 1699, p. 9; CSPC America and West Indies, Vol. 12, Item 1406; Daily Courant, 8-8-22, Issue 6489; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, pp. 110, 129, 131, 223 & 250; Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 18 & 38; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 60; Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 88; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 25, 106, 177 & 254; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p9. 79 & 248; Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, ed., 1923, p. 294; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 26; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 94, 100, 207 & 268; Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, 1825, p. 200; 2 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 166; 3 John Covel, "Diary," Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; 4 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 303 & Shelvocke, p. 268; 5 CSPC America and West Indies, Item 1406; 6 J. R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 176; 7 Dow and Edmonds, p. 60; 8 “2. William Phillips The Voluntary Confession and Discovery of William Phillips, 8 August, 1696. SP 63/358, ff. 127-132”, Ed Fox, ed., Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 25 & “22. David Herriot and Ignatius Pell on Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet, from The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and other Pirates (London, 1719), pp. 44-48”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 106; 9 Daily Courant, 8-8-22, Issue 6489 & The New-England Courant, Issue 45, From Monday June 4. to Monday June 11. 1722; 10 “Ringrose, p. 26 & Sharp, Hacke, p. 15; 11 Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, pp. 110, 129, 131, 145, 223 & 250; 12 Funnell, p. 79; 13 J. R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 167; 14 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 255; 15 Merriman, p. 250; 16 Merriman, p. 268; 17 César De Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 364; 21 Baltharpe, p. 73; 22 Teonge, p. 128; 23 Maria Ketelby, A Collection of Above Three Hundred Receipts, 1714, p. 89; 24 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, pp. 18 & 38; “37. Henry Watson, from Narrative of Mr. Henry Watson, who was taken prisoner by the pirates, 15 August, 1696”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 177; 25 “37. Henry Watson..." Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 177; 26 Dampier, 1700, Part 2, p. 38; 27 John Woodall, The surgions mate, 1617, p. 117-8; 28 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 1, p. xvi; 29 31 John Woodall, The surgions mate, 1617, p. 118, 30 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 164, 191, 250, 317, 340, 511, 801, 1107, 1362, 1413, 1424 & 1511; 31 Salmon, Botanologia..., Book 2, p. 714; 32 John Atkins, The Naval Surgeon, 1734, p. 155; 33 Woodall, p. 134 & 169, 34 Gerard, p. 75; 35 Salmon, Botanologia..., Book 2, p. 787; 36 Salmon, Botanologia..., Book 2, p. 945; 37 Gerard, p. 68; 38 John Moyle, The Experienced Chirurgion, 1703, p. 298; 39 Woodall, p. 117; 40 Woodall,p. 251; 41 Atkins, p. 193; 42 Thomas Tryon, The way to health and long life, 1697, p. 56; 43 Salmon, Botanologia..., Book 2, p. 1251