Cereal Grains in Sailors Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Cereal Grains in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 2

Barley

(Hordeum vulgare)

Called by Sailors: Barley, Barly

Appearance: 7 Times, in 5 Unique Ship Journeys from 5 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Tunis, Tunisia; Oman, Africa; Mocha, Yemen; Chileo Island & Coquimbo, Chile;

Barley was familiar to English sailor, meaning it is never described or discussed in detail by them, typically just being listed among other grains found in the places they visited. John Covel does mention finding bread for sale in Tunis Castle at Tunisia which was made with 'barley flour'. Thomas Bowrey lists 30 bushels of "oats, barley and bran" among the victualling stores put aboard his merchant vessel Mary Galley in 1704, indicating that it was used as food during the ensuing journey, but provides no further detail.2 It almost sounds as if this were feed for animals brought aboard, although none are listed in this document.

Common (vulgare) barley was domesticated from wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) in the Fertile Crescent and is considered one of the "founder crops of Old World agriculture". It was domesticated as early as 8000 BC, with selective breeding resulting in a plant more conducive to use by humans. The result included broader leaves, a shorter stem and awns (the bristle at the top of the plant), shorter and thicker spikes, and larger grains.3

Physician William Salmon mentions a variety of non-wild types of Barley. These include

Photo: Xianmin Chang - Two (l) and Six (r) Eared Barley Ears

1) Common Barley - consisting of several Grassy Leaves and Stalks, sometimes more, sometimes less... [which] rise up to be12, 14, 16, or 18 inches high... at the Tops whereof come forth Ears, having two row of Corn [a generic term for grain in England, referring here to barley kernels], set in order, each inclosed in a Husk, sticking close to the Grain, and having a long rough Aune or Beard thereat... not easily falling out of the Ear"4

2) Bear Barley - similar to common barley, "excepting in the Ear, which is indeed much broader, (tho it has but two rows [of kernels], as the former) for that the Grains lye more straight out, not much sloping upwards, and withal they are something larger"5.

3) Square Barley - "differs only in the Ear, this always having four Rows of Grains, whereas the others have but two"6.

4) Naked Barley - "it has not so many Stalks rising from the Root, as Common Barley has; but it has many rows of Corns in the Ears, which are also inclosed in the Husks, but have not that hard or harsh Skin or Husk upon them... with long rough Awnes or Beards at their ends; and the Grains or Corns are more lank, small, yellow and short, and naked without Husks"7

Artist: Roy Glenn Wiggans

Naked Barley Cultivar, From A classification of the

cultivated varieties of barley (1921)

Salmon makes much of out the appearance of barley plants, although today only two types of barley are identified - two row and six row. "The number of seed rows is determined by the number of fertile flowers; in two-row types only two of the six flower clusters are fertile, whereas all the flowers of six-row barley are fertile."8 Bere barley (sometimes called bear barley) is another name for a type of six-row barley grown in Scotland.9 This may have been the same as Salmon's 'bear barley', although that is not clear from his description. In fact, he doesn't mention a six row barley at all, only one with four rows that calls 'square barley'. However, "Four-row barley... is actually a six-row barley that appears to form four rather than six, because of its thin, elongated head."10 His last category - naked barley - is a cultivar of common barley (Hordeum vulgare var nudum). "Naked barley is simply barley with grains that thresh freely out of the husks or hulls found on normal covered barley. ...The naked mutation, known as nud, is a recessive mutation and is not found in wild barley."11 Today, it is one of many types of barley; as the USDA explains, "Thousands of barley cultivars have been developed for specific uses."12

English Botanist John Gerard only briefly mentions different types of barley. He explains that a

Photo: Institute of Korean Languages - Pearl Barley

barley "eare is armed with long rough & prickly beards or ailes, and set about with sundry ranks somtimes two, otherwhiles three, foure, or six at the most... The grain is included in a long chaffie huske... as Pliny writeth, [barley] is of all grain the softest and least subject to casualtie, yeelding fruit very quickly and profitably."13 Like Salmon's square barely, his three and four 'ranks' are today considered variations of the six-row barley. Scottish gardener Joseph Miller describes common barley, being "an Ear composed of two Rows of Seed or Grain, thick and round in the Middle, and less and slender at each End; having a long Beard growing at the Top of each Grain, with a pretty tough Skin or Bark sticking close to it." He also mentions French Barley, dismissing it as "nothing but common Barley decorticated [having the husk removed], and the Ends taken off in a Mill; and if the Mill be set finer, and it be ground smaller, it is called Pearly Barley."14 Today, pearl or pearled barley refers to barley with both the husk and bran removed.15 Note that everyone mentions how the chaff (which Salmon calls a husk, Miller calls a 'Skin or Bark' and Gerard calls a 'long chaffie huske') had to be removed from the grain.

As food, Gerard says that it can be malted. He suggests this process is well-known in England, but explains it for those who aren't familiar with the process. "First, it is steeped in water until it sweI, then is it taken from the water, and ...spred upon an even floore the thicknesse of some foot and a halfe; and thus it is kept untill it ...send

forth two or three little strings or fangs at the end of each Corne. Then it is spred usually twice a day, each day thinner ...for some eight or ten dayes space, untill it be pretty dry, and then it is dried up with the

Artist: Chris Allen

Heating Malted Barley in a Kiln at Tucker's Maltings, geograph.org.uk

heate of the fire and soused."16 Malted barley could be dried and eaten, although it is mostly fiber and difficult to digest. Gerard also indicates that it can be made into meal or flour, something mentioned as being taken to sea by sailor John Covel.

Salmon lists twenty one different uses of barley including those mentioned and describes each in detail. The majority of his uses concern the creation of alcoholic beverages and medicinals. As food, Salmon says barley can be used to make barley cream, 'maza', bread and polenta.17 Maza is made by toasting barley flour, then adding a liquid (Salmon suggests water, wine, oil and/or honey18), which can then be made into balls of dough (think Matzo balls) or pancakes. The bread is made from barley flower, "with a proportional quantity of Water and Salt" along with leaven or ale yeast. It is kneaded with still more barley flower, left to rest and then made into a loaf and baked. "This Bread is proper to be eaten whilest new, agreeing then most with the Stomach, and nourishing best."19 Salmon describes the processes of making polenta by the Greeks, Italians and physician Galen. The Greeks first steep the grains in water, mash them in a mortar and remove the husks, then dry it and add spices such as salt, flax Seed and coriander. The Italians basically do the same thing without soaking. Galen following the Italian recipe, but leaves out all the spices. Salmon comments that polenta, when ground into a meal, can be used "to make Bread, Cakes, Puddings or Broath"20.

From a humoral perspective, Gerard says Barley has "a certain force to coole and dry in the first degree, according to Galen in his booke of the Faculties of Simples."21 Salmon agrees with Gerard and Galen, while Miller only mentions it's cooling faculty.22

Common and Bear Barley, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes,

By John Gerard (1636)

French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort agrees with the humoral properties, noting barley's ability "to moisten an extenuated [emaciated] Body, thicken the Humours, and qualifie [reduce] the heat of the Blood."23 French botanist Louis Lémery cites the Paracelsian principals associated with barley as "much Oil, and a little essential Salt."24

Medicinally, Gerard cites Dioscorides claims that barley"doth clense, provoke urine, breedeth windinesse, and is an enemie to the stomacke." He adds that barley meal "boiled in an honied water with figs, taketh away inflammations"25. Pitton says it can be used "whole, when we have a mind to cool, cleanse or scour; or clean'd, and excorticated, or husk'd when our intention is to cool and moisten". However, like Gerard, he warns against using it when "there be any remarkable Obstructions in the Bowels for if so, we must either altogether forbear the use of Barley, or else we must mix it with Aperitives [substances which open the bowels]."26

Barley's primary medicinal use arose from various concoctions made using it as a base. Salmon lists a variety of them including 1) rectified spirit, 2) balsam, 3) julep, 4) bath, 3) cataplasm (poultice), 6) plaster and 7) ptisan. There are a wide variety of prescriptions for each of these, but this section only focuses on those Salmon recommended.

1) Spirit of barley is produced by distilling beer or ale, which Salmon simply advises has the same qualities as spirit of wine.

2) Barley balsam is made by boiling ale until it thickens to the consistency of a salve or soft wax. "This being applied warm to the Neck or Throat troubled with... kernels, or other hard Swellings, gives much ease and either discusses [disperse] or resolves them: it is good to resolve contracted Sinews and Tendons, comfort and strengthen weak Nerves and joints and is... excellent... for weakness and pain in the Back and... any part... hurt by spraining, falls blows, or other Accidents."27

3) Salmon lists two recipes for barley julep. The first is made by boiling it in water, removing the barley, adding it to another pot of water and cooking it down along with licorice, strawberry and violet leaves. The result is strained to remove the solids, then combined with syrup of violets. "It provokes Urine, and is very good in Cholerick Fevers." The second is boiled twice like the first, the second time with fennel seeds, then strained. The liquid is then sweetened with the addition of sugar. "It... cools the heat and sharpness of Urine, and helps Pissing Blood, especially if it is caused by the Application of Vesicatories, or Blistering Plaisters. It is good against Coughs, Colds, Wheezings, Hoarsness, Asthma's, &c."28

4) Barley bath was made by boiling four pounds of barley in sufficient water, adding three handfuls each of beet, black hellebor, fumitory, mallow and violet leaves once the barley grains were opened by the boiling. "It is a very effectual thing against Scurff [flaking of the skin], Morphew [skin blemishes], Leprosie, Scabs, Itch [a scabies mite infection], and other breakings out being often used."29 (It would definitely not be used on a ship, however.)

Making a poultice

5) A cataplasm or poultice is a soft, moist concoction, typically applied warm externally to ease pain. Salmon lists five recipes for this, although only the first three are discussed here. The first calls for 12 ounces of barley flour and 3 of fleawort meal in a 'sufficient' amount of water with 2 ounces of honey and oil of lilies added. "This apply'd warm cures Tumors under the Ears, in the Neck and Throat, and other the like places." The second combines 16 ounces of barley flour with 3 ounces each of powdered fenugreek seed, flax seed and rue seed, 2 ounces of melilot and chamomile flowers boiled in a sweet wine. "This apply'd warm, discusses [disperses] Inflamations, expels Wind out of the Bowels, and eases Pains of the Sides." The third uses 12 ounces of barley flower, 3 ounces each of powdered pomegranate peels and myrtle berry boiled in red wine. When "apply'd to the Belly, it is said to stop the Loosness, or other Fluxes of the Belly."30 The other two are fairly simple, relying primarily on barley and being used for the type of skin problems mentioned in the barley bath. Note that the barley is primarily used as a base; the medicinal properties were primarily ascribed to the ingredients added to it.

6) A plaster is basically a poultice which has been allowed to dry and form a hard shell on the part to which it has been applied. (Modern casts are essentially plasters.) Salmon's barley plaster was composed of two pounds of barley flour, a pound of 'tar' (probably pine resin), half a pound of wax and olive oil. "It is said to cure hard Swellings of the Throat and other places... it is an admirable thing to cure the Gout."31

7) Ptisans are nourishing drinks designed to help patients heal. Citing both Hippocrates and Galen as sources, Salmon's prescription is: "Take the best Barly, steep it in Water four Hours or more, then put it into a course Bag, and beat it with a Mallet or wooden Pessle till the Husks come of which take away by washing, dry it in the Sun, and keep it for use. Take of this bulled Barly what you please, and boile it in a sufficient quantity of Water till it breaks [opens], and that the liquor is thick like Cream: this liquor is the Ptisan, which ought to be moderately liquid." He adds that it doesn't upset the stomach or cause gas in the intestines, it quenches thirst and "is profitable both to sick and well"32. He goes on to explain that by the golden age of piracy physicians had added a variety of other ingredients with an eye towards improving it, including almonds, melon and citrullus seeds. However, the striking simplicity of the ancient recipe highlights the importance of barley played in a true ptisan.

Barley, barley meal and French barley were all recommended for use in sea medicines by some authors as explained in the sea surgeon's dispensatory article which can be accessed via the hot linked terms.

1Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 195; John Covel, "Diary," Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 52; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 94; 2 Bowrey, p. 95; 3 A. Badr, K. Müller, R. Schafer-Pregl, H. El Rabey, S. Effgen, H. H. Ibrahim, C. Pozzi, W. Rohde, and F. Salamini, "On the Origin and Domestication History of Barley (Hordeum vulgare)", Molecular Biology and Evolution, Volume 17, Issue 4, April 2000, p. 499; 4 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 1, p. 58; 5, 6, 7 Salmon, p. 59; 8 Gregory J. Noonan, New Brewing Lager Beer, 1996, p. 1; 9 "Bere (grain)". wikipedia.com, gathered 2/8/23; 10 Noonan, p. 6; 11 "Hordeum vulgare var nudum 'Gopal', Naked Barley", www.plantsmap.com, gathered 2/9/23; 12 "BARLEY - Hordeum vulgare", USDA Plant Guide, plants.usda.gov, gathered 2/9/23; 13 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 70; 14 Joseph Miller, Botanicum Officinale, 1721, p. 233; 15 "Pearl Barley", wikipedia.com, gathered 2/9/23; 16 Gerard, p. 71; 17 Salmon, p. 59; 18 Salmon, p. 61;19 Salmon, p. 62;20 Salmon, p. 60-1;21 Gerard, p. 71;22 Salmon, p. 59 & Miller, p. 233; 23 Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, Materia Medica, 1716, p. 381; 24 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 70; 25 Gerard, p. 71; 26 Pitton, p. 381; 27 Salmon, p. 61; 28, 29,30, 31 Salmon, p. 62; 32 Salmon, p. 61

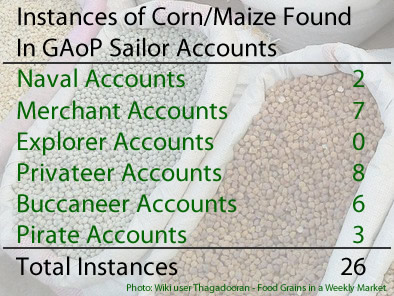

Corn/Maize

(Zea Mays var. Indentata)

Called by Sailors: Corn, Indian Corn, Indian Wheat, Maiz, Maize, Meal, Turkish Wheat

Appearance: 26 Times, in 16 Unique Ship Journeys from 18 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tunis, Tunisia; Cape Corso Castle, Ghana; Principe; Sao Vincente, Cape Verde Islands; St. Helena; Cape of Good Hope, Africa; Myanmar; Trengannu, Malaysia; Siumpu Island, Indonesia; Guam; Barbados; Cape Grace a Dios, Honduras; Trieste to Isla del Carmen, Mexico; Diafara, Panama; Tercera, Brazil; Paita, Peru; Chileo Island, Inuique & La Serena, Chile; Huaquillas & Manta, Ecuador; Florida; Cape Cod, Massachusetts;

Corn aka. maize is the second-most mentioned grain in the sailors accounts

Photo: John Doebley - Teosinte, a Hybrid & Maize

(after rice) from this period, probably because it was so widely used in the West Indies. It was most likely cultivated by humans from the plant teosinte (Zea mays parvaglumis or mexicana) around 9000 years ago in the balsas River Valley of southern-central Mexico. (Although this origin is generally accepted, there are some who still debate this.) It spread throughout the hemisphere, reaching Peru and Chile around 3000 to 5000 years ago and continued to move north. It was first cultivated in New England and New Brunswick around 600 years ago.2 There has been a great deal of debate about whether it was brought to the Old World by Columbus or not. Whatever the case, it spread and by the golden age of piracy, was being grown in places such as India and Malaysia. (One of the phrases used to describe it by period sailors is 'Turkish Wheat'.)

Identifying maize as a grain is somewhat

Photo: wiki user Asbestos - Flint Corn

complicated by our modern understanding of it. When most people today think of 'corn', they tend to think of sweet corn, which has more in common with vegetables than grains. However, the corn found in the sailor's accounts from the golden age of piracy is almost certainly hard kernel corn (today called flint or dent corn) which is left in the field until it dries. (For a discussion of the differences between sweet and dent/flint corn, see corn in the vegetables article.) Flint and dent corns are processed like grains.

In addition, the word 'corn' had a different meaning in England during this time. The Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodites, 1520 -1820 defines corn as "Any GRAIN such as BARLEY, OATS, RYE, WHEAT, but probably not RICE, nor the so-called INDIAN CORN that only became commercially available towards the end of this period in Britain."3 In 1661, Edward Barlow was sailing on the HMS Martin where he noted that "Pembrokeshire also yieldeth the best corn of all sorts of any shire in Wales."4 This is not the type of corn discussed here, it is a reference to the generic meaning, so it is not counted in the above tally. A decade later, when HMS Monk stopped at St. Helena, Barlow notes that they planted plenty of 'Ingen' corn5 (His phonetic spelling is fairly typical of the period.) This instance is counted here.

Theodor de Bry after John White, c1590s.jpg)

Artist: Theodor de Bry after John White

The Village of Secodan with a Corn Field, Algonquin Natives

"They sow their corn with a certain distance, noted by H [middle right

garden], otherwise one stalk would choke the growth of another and

the corn would not come unto his ripeness G [above H], for the leaves

thereof are large, like unto the leaves of great reeds." (Thomas Hariot)

The confusion over the English use of the word complicates effective identification of the numbers... but perhaps not as much as it first seems. The majority of the entries counted here specifically identify corn as 'Indian corn' or 'maize'. In addition, one entry refers to 'Turkish wheat'. Four citations counted here only use the word 'corn', but their location in New World makes it likely that they mean the yellow, cob-held grain.6 Two 'corn' only mentions come from the Cape of Good Hope7 where the Dutch specifically cultivated 'Indian corn' after their initial attempts to plant wheat failed.8 The most debatable two entries come from Captain Alexander Hamilton, who only refers to what he found in the East Indies as 'corn'9; Maize was definitely grown there during this period10, but so were other grains.

Semantics and history debates aside, the period authors do have quite a bit to say about the price of maize. Writing in the General History of the Pirates about the West African islands of São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón, sea surgeon John Atkins describes corn as one of "the common Victualling of our Slave Ships, and is afforded here at 1000 Heads for two Dollars."11 Buccaneer Basil Ringrose pointed out in August of 1680 that the natives of Manta, Ecuador 'afforded' "plenty of Indian Corn", although he doesn't say whether they purchased or stole it.12 Edward Cooke mentioned buying "100 Baskets of Maiz or Indian Wheat, at 1 Do[llar]. 4 R. [real - 1/8 of a dollar] per 2 Baskets"13.

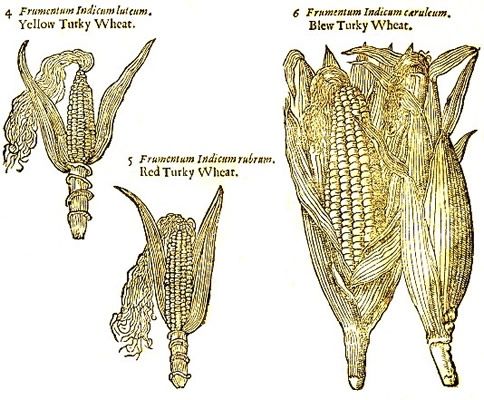

John Atkins describes the corn plants he found growing at São Tomé,

Variously Colored Flint/Dent Corn, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, By John Gerard

(1636) Note: The yellow coloring is from the aging of the paper. Some of it has been removed for clarity.

Príncipe, and Annobón: "This Corn grows eight or nine Foot high, on a hard Reed or Stick, shooting forth, at every six Inches Height, some long Leaves; it has always an Ear, or rather Head, at Top, of, perhaps, 400 Fold Encrease; and often two, three, or more, Midway."14 John Taylor a mathematician and chemist who lived in Jamaica in 1687 explains, "Maize or Indian corn groweth here in ears about one foot long and as bigg as a man's wrist having some 500 graines in one eare and sometimes three eares on one stalck."15 Botanist John Gerard says, "Of Turky Corns there be divers sorts... consisting of sundry coloured Graines, wherein the difference is easie to be discerned; and for the better explanation of the same, I have set forth to your view certain eares of different colours in their ful and perfect ripenesse,and such as they shew themselves to be when their skin or filme doth open it selfe"16. Of course, his book is not in color, so the images (above) are of limited value without the explanation. Physician William Salmon expands upon these descriptions.

Photo: Jonathan Kington - Female Inloresence {Flower] or Spaix of Maize

After the plant 'flowers', "come forth the Ears at the joints of the Stalks with the Leaves... which have many Leaves enclosing them, and are smallest at the Top, with a Small long Bush of Hairs or Threads, hanging down gathered. ...The Leaves Enclosing the Ear being taken away, the Head or Ear appears, much like to a long Cylinder (not a Cone) set with 6, 8, or 10 rows of Grains, as large almost as Pease, and sometimes larger; not fully round, but flat on the sides which join one to another, orderly and very closely set together, of the same Color on the outside as the Bloomings [flowers] were, viz. either White, Yellow, Red or Blew only, or of some or all of those Colors together; the whole Grain is hard and brittle, its external Husk being very hard almost like a Shell, but its inward Pulp, when grownd into Meal or Flower, almost as white as Snow17.

The 'flowering' of maize that Salmon mentions is a spadix or "fleshy spike with reduced flowers."18 Most people call the male spadix a tassel and the female spadix corn silk.

As food, maize was most often ground into cornmeal or flour, as Salmon pointed out. To the Dutch in New York in the late seventeenth century, "Maize, the most unfamiliar of new foods was generally prepared as though it was a European grain; it was simply substituted for other ground grains in boiled porridges."19Surgeon John Atkins notes that when HMS Swallow stopped at Cape Corso Castle in Ghana, he found "Indian Corn and a great deal of Canky, to be bought at Market."20 Kankie is a type of bread found in North African which is made from maize flour.21 French botanist Louis Lémery talks about corn bread, mentioning how heavy it is.22 Gerard comments, "The bread which is made thereof is meanely white, without bran: it is hard and dry as Biskett is, and hath in it no clamminesse at all"23.

Photo: Gabriel Larohe - Making Cornmeal Pancakes (Gorditas)

Salmon says that bread, cakes and puddings can be made using corn flour, the bread of which "whilst New, is wonderful Sweet, beyond any that can be made of European Wheat; but being Stale, it eats something harsh, and more unpleasing"24. Privateer George Shelvocke explained that when his vessel Happy Delivery was near Diafara, Panama, they had "Indian corn; and, for the present use were entertain'd with a wholesome breakfast of hot cake and milk, a diet we had been long unacquainted with"25.

Physician Salmon talks about a variety of other ways of eating corn. His first recipe is for boiled maize. "The Corn is first steeped a little in warm Water, then beaten in a wooden Mortar with a wooden Pestle, till all the external hard Hull is beaten off; then it is boiled in Water till the Grain is perfectly soft and burst in the boiling"26. This he says can be eaten with salt and butter or milk, cream, wine and sugar. John Taylor notes that in Jamaica, "come they pound to flower and boyle ...for their Negro slaves which soe order'd they call it hommone after the Indian name."27 Physician Salmon explains how hominy was made during the period. "...take either ...boiled Maize, or ...Pultage... to which they add a sufficient quantity of Milk, which being boiled... Some put in so much Milk as to make it a little thinner, according as every one likes. They generally eat it, being made Savory with Salt and Butter, and some put Sugar to it."28 Note that this is made differently than hominy today.

No one defines traditional humoral properties for maize, almost certainly because it was not familiar to the ancient physicians like Hippocrates, Galen and Dioscorides on whom the seventeenth and eighteenth century medical men relied for such information. As Gerard puts it, "Wee have as yet no certaine proofe or experience concerning the vertues of this kinde of Corne"29. (Recall that 'corn' was a generic

Corn or Turkey Wheat, From Theatrum Botanicum the Theater

of Plants,

By

John Parkinson (1640)

term for a variety of grains in England.) Louis Lémery says that from a Paracelsian perspective, "It contains much Oil and essential Salt."30

Medicinally, most of the botanist and physicians comment on the usefulness of individual preparations of maize. Corn meal and its progeny received the most comment. Gerard says that corn bread "is of hard digestion, and yeeldeth to the body little or no nourishment; it slowly descendeth, and bindeth the belly". He dismisses the Native American use of it because they are "constrained to make a vertue of necessitie,and thinke it a good food: Whereas we may easily judge, that it nourisheth but Iittle, and is of hard and evill digestion, a more convenient food for swine than for man."31 Lémery warns that corn bread "does not agree with any but such as are of a robust and hail Constitution."32

Physician Salmon has the most to say about the medicinal uses for maize. He doesn't talk much about the bread, other than to suggest that combining corn flour with wheat flour will make the bread more moist, addressing Gerard's complaint. Of boiled maize, he says "it admirably nourishes and strengthens, and makes the Country Man able to go thro' Labour and Business"33 This agrees with Lémery's assessment that maize it best for robust workers. Salmon ascribes the same properties to pultage. Of hominy, he says, "It has all the former Virtues and Effects [of boiled maize], besides it cleanses the Bowels, and always keeps them Soluble, at least from being Costive [constipated]." This is the opposite of what Gerard says about corn bread. Salmon also lists a cataplasm or poultice which, when made with "flower mixed with Leven, and brought to a Consistency with Oil of the Seeds Ricinus or Palma Christi [castor oil], or fresh Butter; being applyed, is said to ripen Apostems [pus-filled abscesses]."34

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 59 & 92; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 199, 239 & 312; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol. 2, 1712, p. 9, 15, 43 & 68; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 128; Jonathan Dickenson, God's Protecting Providence, 1700, p. 49; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 63; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 316; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 150; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 353 & 439; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 183; Ravaneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 336, 415 & 460; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 20; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 26; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 43; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 100, 189, 268 & 300; 2 W.F. Tracy, "Vegetable Uses of Maize (Corn) in Pre-Columbian America", Horticultural Science, Vol. 34, Aug, 1999, p. 812; 3 "Corn", Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1520-1820, british-history.ac.uk, gathered 11/3/22; 4 Barlow, p. 74; 5 Barlow, p. 199; 6 Dickinson (Florida), p. 49; de Lussan (Huaquillas, Ecuador), p. 415; Sharp (la Serena, Chile), p. 43; & Shelvocke (Iquique, Chile), p. 268;7 Cooke, p. 68 & Barlow, p. 239; 8 John Noble, History, Productions and Resources of the Cape of Good Hope, 1886, p. 54; 9 Hamilton (Myanmar & Trengannu, Malaysia), pp. 353 & 439; 10 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 71; 11 Atkins writing in Johnson, p. 188; 12 Ringrose, p. 20; 13 Cooke, p. 9; 14 Atkins writing in Johnson, p. 188; 15 John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 221; 13 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 82; 17 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 1253;18 "spadix", en.wiktionary.org, gathered 2/14/23; 19 Meta F. Janowitz, "Indian Corn and Dutch Pots: Seventeenth-Century Foodways in New Amsterdam/New York", Historical Archaeology, Vol. 27, No. 2, 1993, p. 20; 20 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 92; 21 "Kankie", wiktionary.com, gathered 2/15/23; 22 Lémery, p. 71; 23 Gerard, p. 83; 24 Salmon, p. 1254; 25 Shelvocke, p. 300; 26 Salmon, p. 1253; 27 Taylor, p. 221; 28 Salmon, p. 1254; 29 Gerard, p. 83; 30 Lémery, p. 71; 31 Gerard, p. 83; 32 Lémery, p. 71; 33 Salmon, p. 1253; 34 Salmon, p. 1254

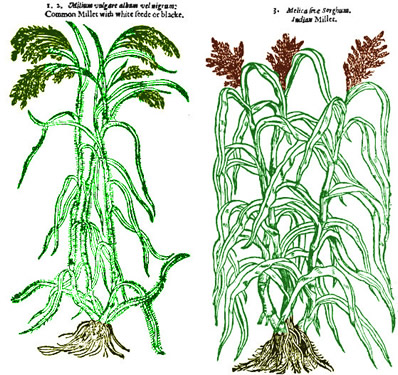

Millet & Guinea Corn

(Poaceae)

Called by Sailors: Guinea Corn, Milhio, Millet

Appearance: 4 Times, in 4 Unique Ship Journeys from 4 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Tunis, Tunisia; Monrovia, Liberia; Siumpu Island, Indonesia; Barbados;

Millet, sometimes called Guinea Corn in the sailor's accounts, is the least supported grains on ships. 'Millet' is found once in a sailor's account as is 'milhio' (both instances being on the West African coast). The term Guinea corn occurs in two different sailors accounts, once in Barbados and the other time in the East Indies. Both differentiate it from maize, which one calls 'Indian corn' and the other 'Turkey wheat'. So the vagueness of terminology used here make identification more challenging. Word meanings were frequently less precise during this period.

The first issue is with the word 'milhio'. Sea surgeon John Atkins is the sailor who mentions milhio, but without explanation, listing it as one of several things available to ships stopping at Cape Montzerado (present-day Monrovia, Liberia, located on what was called the Ivory Coast of Africa) in 1721.2 Dutch West India Company

Photo: flickr user cheese - Red Sorghum Grains with Bran Still Attached

merchant Willem Bosman, stationed in Ghana on the African Ivory Coast for 14 years beginning in 1688, describes the milhio he encountered there. "The large Milhio is by most taken to be the Turkish Wheat [maize]"3. This suggests that it is possible that Atkins was talking about maize. However, in addition to finding 'milhio' in Africa, Atkins identified a grain he called "Indian Corn" (maize) at Cape Corso Castle that same year4. Since he specifically identified maize there, he would not likely have referred to it by another name if he had found the same thing in Cape Montzerado; grains of maize are quite distinctive.

Bosman describes a "second sort of Milhio called by the Portuguese Maiz, [which] is a Grain like the Coriander-Seed... and very much resembles our slighter sort of Rye."4 Coriander seeds are distinctively round, being about 3-5 mm in diameter - much smaller and differently shaped than corn.5 Atkins did not provide a description of his 'milhio', so it is impossible to be certain what he was referring to. However, given that both men were located on the Ivory Coast of Africa and Atkins called maize Indian corn in another entry in his book, it seems likely that he was referring to something other than corn. Bosman's description matches millet, which is why Atkins 'milhio' is counted here.

The second issue is with the phrase 'Guinea corn'. Although it has 'corn' in the name, this was a generic term in England,6 Today, guinea corn is defined as "any of several grain sorghums" or "a variegated

Sorghum Grains with Bran Removed

[

multicolored] Indian corn".7 Since both of the original accounts include maize or 'Indian corn' in the same list as guinea corn, the second definition can be discarded.

Is Guinea corn sorghum? There are several descriptions of the guinea corn from this time period. Mathematician John Taylor described the guinea corn in Jamaica in 1687 as "a small grain, round and of the dementions of indigo seed, being filled with a curious whit[e] flower and hath a very thinn husk"8. (Indigo seeds are about 2-4 mm in diameter from my measurement.) Buccaneer and explorer William Dampier cites a description of guinea corn that Woodes Rogers found at Natal in South-Eastern Africa. "They have Guinea Corn, which is ...a small sort of Grain no bigger than Mustard-seed"9. Mustard seeds are also about 2-3 mm in diameter. physician Hans Sloane says that the guinea corn he found in Jamaica is "a round Seed of a whitish yellow colour, not so big as that sort of Barley call'd commonly Pearl Barley."10 The smallest barley seed is about 4 mm in diameter.11

The sizes listed aren't much different than sorghum (3-5mm), although some of the comparison seeds mentioned are smaller than the smallest sorghum seeds. Sorghum millet can be white, yellow, or red in color, which fits the color Sloane mentioned. When the sorghum bran (thin shell) is removed, the inside is a pearly white color. Overall, sorghum seems like a pretty good candidate for Guinea corn as well as Bosman's milhio.

Photo: Gaurav Dhwaj Khadka - White Proso Millet Grains

There are other types of millet that grow in Africa. Proso millet (Poaceae Panicum miliaceum), also referred to as common millet, has seeds that are about 3-4 mm in diameter in colors of white, golden yellow, brown & straw white

colored. Pearl millet (Poaceae cenchrus americanus) is about 3-5 mm in diameter and "can be a nearly white, pale yellow, brown, grey, slate blue or purple colour."12 They could also be what is described.

The origins of sorghum (Poaceae sorghum) are not clear. There are about twenty-five species of sorghum, only one of which, Poaceae sorghum bicolor, has been cultivated as a grain used for human consumption. The rest are considered wild.13 These are confined to Africa south of the Sahara Desert and possibly Yemen. It is unclear when it was domesticated; the earliest archeological remains appear to be those found in the Indian subcontinent, dating to around 2 BC. Since wild sorghum does not grow there, these are not native and must have been brought there from Africa.14

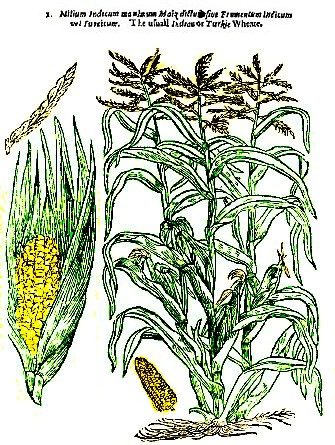

The botanists and physicians from around the period of the golden age of piracy identify two or three different types of millet. John Parkinson's book is typical of this, first identifying a common white millet, the plant of which consists of

Common and Sorghum Millet Plants, From Theatrum Botanicum - the Theater

of Plants, By John Parkinson (1640)

many hard joynted tall stalkes full of a white Pith, yet soft and a little hairy or downy on the outside, with long and large Reede-like leaves at them compassing one another, the toppes of the stalkes are furnished with a number of whitish yellow long sprigges like feathers, bowing downe their head, set all along with small seede inclosed in a whitish huske, which being taken forth are of a shining pale yellowish or whitish colour somewhat hard15

Proso millet has hairy stalks, sorghum does not. Since proso millet is also called common millet, this is likely what Parkinson is talking about. He says the second millet is the same type as the first, except "the juba or tuft is brownish, so is the seede also blackish and shining, very like else to the other." His third millet "is in all the parts thereof larger, greater and higher than the former, rising to be five or six foot high or more, the stalkes are full of joynts and large long leaves at them, the juba or tuft standeth upright and boweth not downe the head as the other, whereon stand the seede as big but not flat as Lentills somewhat round, and eyther whitish, yellow, red or blackish, hard and shining"16. He specifically calls it Sorghum or Indian Millet.

Merchant Bosman explains that Ante [which was somewhere east of modern Axim, possibly near modern Achenem or Akwidwaa] during times of Peace and good crop growth "produces prodigious Quantities [of millet]; I have seen it bought, and have also bought my self, on Thousand Stems or

Photo: TK Naliaka - Making Millet Meal (Flour)

Stalks for six, seven, eight and nine Takoes, each Takoe amounting to about four pence farthing EnglishMoney, and a Sack amounting at highest not to two and twenty pence. Thus Corn [millet], in time of Peace, is the cheapest of all Provisions"17. However, he also notes that it is more expensive in nearby Axim because they don't grow much of it there.

As food, millet is ground to make meal which can then be used to make cake, bread or puddings.18 Parkinson says "it is some times made into bread but it is very brittle, not having any tenacitie in it whereby it nourisheth little". He adds that it is "much used in Gernany boyled in milke with some Sugar put unto it and Mattholius saith that at Verona the bread thereof is eaten with great delight while it is hot, by reason of the sweetenesse, but being old it is hard and utterly unpleasant"19. John Taylor is much more upbeat, suggesting that millet "when blanch't and boyled eat[s] full as good as rice or French barly [and] have the same good properties."20

From a humoral standpoint, nearly everyone refers to Galen, explaining that millet "is cold in the

Photo: Wiki user Rasbak - Sorghum Millet Plants

first degree, ...and dry in the third, or in the lat[t]er end of the second [degree]"21. Salmon equivocates on the first property, suggesting millet "is temperate in respect to heat or coldness, and is drying in the second Degree."22 French botanist Louis Lémery provides the Paracelsian perspective, crediting millet with the principles of "much Oil, and a little essential

Salt." He says that it is "proper

to suppress and embarass the sharp humors of

the Breast: It's a little Binding, and allays the too violent Motions of the Humours." He touches on the bodily temperaments as well. "It agrees at all times, and to any Age, with Persons of a bilous Constitution, and such as have

a good Digestion; but melancholy People, and those that abound with gross Humours, ought to abstain from it."23

From a medical perspective, Salmon says millet is "Abstersive, Astringent, Diuretick, and Antifebritick. ...It restores in Consumptions and abates the heat of Fevers: Stops Fluxes of the Bowels and of the Womb."24 Sloane agrees that because it is dry, it "is good in Dysenteries."25 Salmon explains that millet meal (flour) "Strengthens the Stomach and Belly: Milk thickened with its Flower and given daily, stops Diarrheas and other Fluxes of the Bowels: Broth made of choice Beer, and thickned with the fine Flower hereof restores the Tone of the Stomach and Intrails admirably."26 This is probably one of the few times you'll see a physician suggesting that beer will tone your stomach. Gerard and Sloan suggest that the meal "mixed with tar is layd to the bitings of Serpents and all venomous beasts"27, presumably with the idea that its dry nature will pull the poison away from the wound. Gerard, Parkinson and Sloan each recommend parching millet and putting it in linen bags that can be applied to the stomach to relieve "the Belly-ach and Cholick... Griping of the Guts, Stitches, Pleurisies, and other Illnesses of like Kind."28 The overlap in recommendations is interesting; Salmon may have been cribbing from Gerard and Parkinson's herbals.

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 59; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 312; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 43; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; 2 Atkins, p. 59; 3 William Bosman, A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, 1705, p. 296; 4 Atkins, p. 92; 4 See Yalçın Coşkuner and Erşan Karababa, "Physical properties of coriander seeds (Coriandrum sativum L.)", Journal of Food Engineering, Volume 80, Issue 2, May 2007 & "Close up of millet grains", tconnectingagriculture.com, gathered 2/16/23; 5 Bosman, p. 297; 6 "Any GRAIN such as BARLEY, OATS, RYE, WHEAT, but probably not RICE, nor the so-called INDIAN CORN that only became commercially available towards the end of this period [early 1800s] in Britain." Ftom "Corn", Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1520-1820, british-history.ac.uk, gathered 11/3/22; 7 "Guinea corn", www.merriam-webster.com, gathered 2/16/23; 8 John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 221; 9 William Dampier, "Captain Dampier, His Discourse on the Trade Winds", A Supplement of the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 110; 10 Hans Sloane, A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, Vol. 1, 1707, p. 104; 11 "Barleycorn (unit)", wikipedia.com, gathered 2/16/23; 12 "Close up of millet grains", gathered 2/16/23; 13 See J. M. J. De Wet and J. R. Harlan, "The Origin and Domestication of Sorghum bicolor", Economic Botany, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Apr-Jun, 1971), p. 128 & "Sorghum", wikipedia.com, gathered 2/17/23; 14 Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, 2000, p. 88; 15,16 John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1136; 17 Bosman, p. 298; 18 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 714; 19 Parkinson, p. 1137; 20 Taylor, p. 221; 21 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 80; 22 Salmon, p. 714; 23 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 65; 24 Salmon, p. 714; 25 Sloane, p. 104; 26 Salmon, p. 714; 27 Gerard, p. 80 & Salmon, p. 714; 28 Salmon, p. 714, Parkinson, p. 1137 & Gerard, p. 80