Cereal Grains in Sailors Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Cereal Grains in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 3

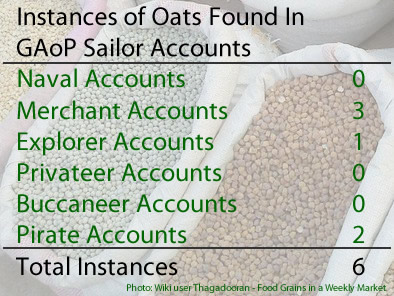

Oats

(Poaceae Avena sativa, Poaceae Avena nuda)

Called by Sailors: Burgoo (Oatmeal), Groats, Grouts (both meaning crushed oats), Oats, Oatmeal

Appearance: 6 Times, in 6 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Dampier Archipelago, Australia; Barbadoes; Beaufort, North Carolina, North America

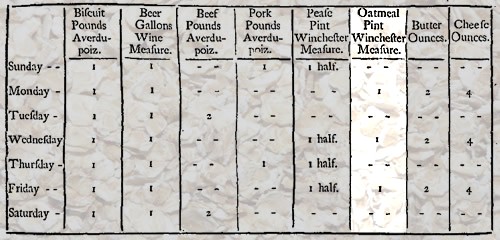

Oats are one of three grains provided to sailors in the Royal Navy in the form of oatmeal. The others are wheat, which was used to make biscuit, and rice. Like rice, oatmeal was originally a substitute food, which in 1691, the navy ordered "could be issued in lieu of fish, 1 gallon of oatmeal being reckoned equivalent to 1 cod."2 According to the 1677 victualling contract Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays were fish days, the days that this substitution could be made. In 1701, the navy board reiterated this order, giving victuallers the option "to deliver clean and well dressed oatmeal in lieu of sized fish (where the Principal Officers and

Photo: Kai Stachowiak

Sailors Meal Plan, From Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty's service (1731)

Commissioners of the Navy shall direct your so doing), you are at liberty to pursue this practice (which hath been of long standing in the Navy) where you shall judge it may be for the Service, unless the contrary shall be ordered' by the Admiralty or Navy Board."3 By 1703, the Victualling Board had removed fish from the menu entirely, declaring that on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays, "no flesh is allowed [to the naval sailors], they have oatmeal, butter, and cheese; so that there are no more than two days in each week whereon they really eat salt provisions while in sea victualling, and even on those two days are sometimes relieved by flour and suet for pudding in lieu of beef."4 As a result, by the printing in 1731 of the Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea there is no evidence of fish in the standard diet, only oatmeal.5

Oatmeal was delivered to the navy on contract and supplied either from Portsmouth or London.6 At most of the outports, the oatmeal was supplied by London dealers

Artist: Phillips Galle

Loading a Ship, Doris Personifying Sea Trade (1574)

who purchased it through agents.7 "Oatmeal contracts were frequent in number, with short delivery dates, ranging from immediately to two months, though some of the larger contracts provided for deliveries as demanded... Quantities to be delivered on a single contract varied from 20 quarters to 400. The prices might hold for a number of months on one level or they might vary from one contract to another. Most of the contracting was done in the winter and spring."8

Historian John Keevil notes that the substitution of oatmeal for fish "was reluctantly accepted in official circles and aroused open opposition among the men."9 In 1709, Sir George Byng, Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, wrote the Secretary of Admiralty to recommend, "that all such oatmeal as is sent out abroad might be whole oatmeal; having found it to be much more to the satisfaction of the men, preserves itself a much longer time, and is in every respect to be preferred before the ground oatmeal now used among us."10

Of the three grains sanctioned by the English Navy for the sailors diets, oats have the lowest support by far from the period sailors accounts. This could reflect the sailor's preferences from the period, although this cannot be effectively supported. As with some of the other naval sea victual staples, no support for oatmeal is found in the naval accounts. This is likely because it was so familiar to them. In fact, if Keevil's assertion that the sailors were vocal in opposition to oatmeal replacing fish, it is surprising there are not some examples of this found in the naval accounts.

George Byng's comment raises the question about the type of oatmeal was served in the navy. Like all grains, oats must have their hulls removed to make them edible to humans. Once hulled, the oat can be used whole as Byng suggests, which is sometimes called a 'groat'. (This term appears in barber-surgeon Dietz's account, meaning the men aboard the whaler Hope of Rotterdam were eating whole oat oatmeal.11) However, the fact that Byng recommended that the navy always provide it suggests that some of their contractors were providing a different form of oatmeal.

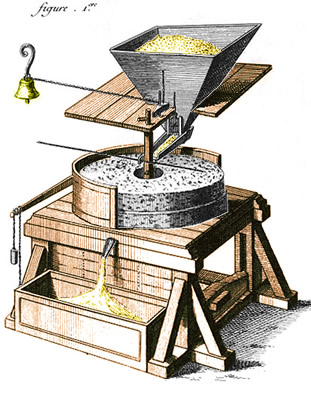

John Worlidge and Nathan Bailey describe the process of making Oatmeal in the early eighteenth century:

Small Stone Mill Detials, From l'Encyclopedie, Vol. 1 (1765)

...to make good and perfect Oat-meal, the Oats must be first exceedingly well dried, then put them on the Mill, which may either be Water-mill, Wind-mill, or Horse-mill, the last which is the best; and do no more but crush or hull them; that is, carry the [grinding] Stones so large [position them so far apart], that they may do no more but crush the Husk from the Kernels either with the Wind or Fan; and finding them of an indifferent cleanness (for it is impossible to hull them all clean at first) you shall them put them on again, and making the Mill go a little closer [position the mill stones closer together], run them through the Mill again; ...and such Greets [groats] or Kernels as are clean hulled, and well cut may be laid by, and the rest you shall run thro' the Mill again a third time... in which time all will be perfect, and the Greets or full Kernels will separate from the smaller Oatmeal... you shall ever have two sorts; that is, the full whole Greet or Kernel, and small Dust Oatmeal...

...at Sea, &c. a more wholsome and pleasant Meat [food] cannot be eat, than these whole Greets boiled in Water till they burst, and then mixed with Butter, and so eaten with Spoons, called by your Sea-fairing Men, Loblolly...12

This description predates Byng's request of 1709, suggesting that whole oats were provided for use as oatmeal at sea when it was written, previous to 1704. Byng describes the oatmeal they were receiving as ground, which sounds like the 'small Dust Oatmeal' mentioned by Worlidge and Bailey. They note that this ground oatmeal can provide a coarser food, "which is as it were the Dregs or grosser substance thereof, called Gird-Brew, which is a well-filling and sufficient Meat for Servants and Labouring-men."13 Sailors were certainly laboring men and it is possible that the navy (or its contractors at least) thought it might serve just as well as whole grain oats.

Other than a couple of simple recipes, the period sailors do not have much to say about oats.

Photo: Wiki user Yonygg - Groats or Hulled Oats

The most interesting citation come from the victualling stores loaded on the merchant vessel Mary Galley in 1704 for a trip to India. They include 60 bushels of "Oatmeal and Grouts" ["Oats hull'd or great Oatmeal"14] as well as 30 bushels of "Oats, barly and bran"15. Because this is just a list of provisions, the purpose of bringing raw oats as well as meal is not clear.

Oats do get some attention from pirates. Captain Bartholomew Roberts ships thought fit to take "ten Casks of Oatmeal" from a Bristol ship they captured off Barbados in 1720.16 During the trial of Roberts' men in 1722, Harry Glasby testified that pirate James Phillips "was a Volunteer, and used to say, they took him with a little Sugar’d Burgoo"17. This hints at the limited value placed on oatmeal.

The general consensus of the herbalists is that there are two kinds of oats - wild

(Avena fatua) and 'manured' or cultivated oats. The cultivated oats were what was used as food, being

Photo: H. Zell - Common Oats with Hulls

further divided into two types: common oats (Avena sativa) and 'naked' oats (Avena nuda), which John Gerard explains "immediately as they be threshed, without helpe of a Mill become Otemeale fit for our use."18 The two authors who describe oats do so by comparison to other grains. Physician William Salmon says that the "within every one of [the common oat]

Husks lies a small and long round Grain, somewhat like unto Rye, but longer, and more pointed, covered with a hard, horny, shining Husk, sticking close to it."19 Botanist Joseph Miller chooses another comparison grain, suggesting that the oat "Grain is longer,

slenderer and smoother than Barley, cover'd with a loose Husk or Skin."20 He doesn't differentiate between common oats and naked ones. Salmon does, noting that the naked oat plant is basically the same, "saving that the Grain being somewhat smaller and whiter, lyes not so fast enclosed in the Husk, but is very easily rubbed out with ones Hand."21

As food, oatmeal is the order of the day. Note that when period authors refer to oatmeal, they are talking about dry meal. Like Gerard, Salmon explains that "Naked Oats, as soon as they are Thrashed or Rubbed out, without help of a Mill, become Oat Meal, and fit for use"22. French Botanist Louis Lémery (who calls oatmeal 'groot', or "Oats divested of its Husk and outer Parts, and made into large Meal") advises choosing "such as are new, well cleaned, white, and not musty, and made of good Oats."23

Photo: Bill Ebbeson - Oatmeal

Several authors talk about the preparation of oatmeal. It has already been shown how at least one group of pirates added sugar to burgoo, the combination of oat meal with water. While exploring the wilds of Australia, Dampier further establishes this, noting that while some brackish water they found didn't look fit to drink, it "would serve to boil our Oatmeal, for Burgoo"24. Gerard rather poetically comments "Otemeale is good for to make a faire and wel coloured maid to looke like a cake of tallow [appear pale], especially if she take next her stomacke a good draught of strong vinegre after it."25 Salmon says oatmeal is used to "make Bread, Cakes, Puddings, &c. and being Malted,

are also by some People made into Ale or Drink, very good, and exceeding in pleasantness that made of Barly."26 Francis Rogers reported that when the merchant ship Arabia was at sea near the Cape Verde Islands, they speared two dolphins, "which made us a most noble supper, they being the most delicate of fish, either boiled (which way with a piece of pork and oatmeal or rice, they make good broth), or cut in stakes and fried like veal cutlets, or soused."27

Perhaps the most interesting recipe (if it is a recipe) comes from sea surgeon Johann Dietz, who served on a whaling ship around 1690. "On at least three days of the week we ate groats [hulled oats], pease, lentils and stock fish, boiled, and pickled beef, pork and mutton, with bacon and a great deal of butter. When the men were at meals, if it was windy one of them had always to hold the mess-bowl, that is, a great wooden bowl."28 Because it was served in a 'great wooden bowl... and a great deal of butter", it sounds as if it may have been all mixed together.

Humorally, Galen says oats are dry and cold, with Salmon adding that "according to our Opinion in the beginning of the first Degree". He later adds that oatmeal gruel "sweetens the Juices and Lympha, and takes away the Acrimony of the Humors"29.

Common and Naked Oat Plants, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, By John Gerard (1636)

Navy physician William Cockburn said that oatmeal was "very fit to correct that thickness of the humours and costiveness [constipation], that are the unavoidable consequences of the [sailor's] diet join'd with the least idleness: for Oats... preserve that motion, that's requisite to make a due perspiration [to cleanse the bad humors from the body], by adding spirits to the blood"30. Lémery gives the Paracelsian principals as "a midling quantity of essential Salt, and much Oil." He says eating oatmeal is "fit to embarass

the sharp Salts in the Breast, Blood, and other Humours". In addition, "It agrees at all times, with every Age, and all sorts of Constitutions, and especially with those whose Humours are very subtil, sharp, and in an extraordinary Motion."31

Salmon says that "made into Water Gruel, or Milk Porridge, they certainly open and loosen the belly."32 Cockburn agrees, explaining that oats "by their cleansing power and vertue to keep the belly open [and so prevent constipation], this Burgoo victualling is highly necessary for our seafaring people."33 Similar to Salmon, Lémery recommends "to afford good Nourishment to the Parts... use [oatmeal] by way of Decoction made with Water and Milk."34

Gerard and Salmon both launch into medicinal concoctions which are made with oats. They each recommend using oatmeal to make a cataplasm. Gerard explains that this "dries and moderately

Photo: Henrik Sendelbach - Common Oats (Avena Sativa)

discusses, and that without biting [causing pain]; for it hath sornewhat a coole temper, with some astriction [ability to stop bleeding and close wounds], so that it is good against scourings [inflammation]."35 Salmon mentions several other uses, including

1. Oatmeal - "Made very hot in a Frying-Pan, and put into a Linnen Bag, and applyed to the Stomach or Side pained, it gives ease in the Colick, and takes away Pains and Stitches in the Side"

2. Bread, Cakes, Pudding, Gruel or Broth - "They stop Fluxes of the Bowels, nourish much, and restore in Consumptions." He adds that when oat bread, cakes and pudding are made with beef broth and raisins, they "always loosen the Belly."

3. Cream of Oatmeal - "It is made by boiling with Water, the Head being continually scumm'd off: or it is made with the very finest of the Flower, first boiled with a little Water, then adding Milk to it, it is boiled to a Consistency." When eaten with salt and butter, "it loosens the Belly, and by continuing there of makes it soluble" like the broth, "but much more delicious or pleasant: Mixt with fine Sugar or Sugar Candy, and so given, it is profitable for such as have gotten a Cold or

Cough."4. Oatmeal Cataplasm - In addition to the uses also mentioned by Gerard, Salmon says "it allays Inflamations, and strengthens the part it is applyed to. If mixt with Oil of Bays and applyed, its good against the Itch and Leprosie: it dissolves or discusses hard Apostems; and is profitable against a Fistula in Ano, or in the Fundament."

5. Malted Oats - "A strong Decoction of it is made into a Syrup with Hony, is good against an Asthma, as also for Coughs, Colds, Wheezings, shortness of Breath, &c. Mixt with Turpentine and Yolk of an Egg, it Digests old, running and eating Ulcers, and facilitates their Cure.36

Oatmeal had an important place as food for the sick at sea in medicine. Sea surgeon John Moyle recommended that the day following a fight at sea, all the wounded men should be fed a "Grewel of Oatmeal, Currants, and Spice; and when 'tis ready, let it be sweetned with Sugar, and give thereof to each of them, and let them have it twice a day at least"37. In his second book, Moyle expanded the use of this gruel, "both to the wounded and to the sick; and there is alwayes Oatmeal ready on board; the which things do make wholesome Diet, for such, whom salt victuals, and bad Drink would harm."38 Among other foods, sea surgeon John Woodall recommended "an oatmeale caudell [caudal - a syrupy gruel] would not bee amisse of a little beere or wine, with the yoIke of an egge, and a little sugar made warme" as a drink to be given to a patient being treated for scurvy.39

1 Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p, 195; William Dampier, "Part 1", A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 150; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 128; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 215; Pyrates Lately taken by Captain OGLE, 1723, p. 70; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 151; 2 R.D. Merriman, The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 236; 3 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 254; 4 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 268; 5 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 60; 6 Paula K. Watson, “The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714”, University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 88; 7 Watson, p. 120; 8 Watson, p. 104-5; 9 John Keevil, Medicine and the Navy, 1200-1900, Volume II - 1649-1714, 1958, p. 91; 10 Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, p. 291; 11 Dietz, p. 128; 12,13 John Worlidge & Nathan Bailey, "Oat-Meal", Dictionarium Rusticum, Urbanicum & Botanicum, 1704, not paginated; 14 Nathan Bailey, "Groats" Universal etymological English dictionary, 1724, not paginated;15 Bowrey, p. 195; 16 Defoe (Charles Johnson), p. 215; 17 "Pyrates Lately taken by Captain OGLE", p. 70; 18 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 74; 19 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 786; 20 Joseph Miller, Botanicum Officinale, 1721, p. 68; 21 Salmon, p. 786; 22 Salmon, p. 787; 23 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 64; 24 Dampier, p. 150; 25 Gerard, p. 75; 26 Salmon, p. 787; 27 Rogers, p. 151; 28 Dietz, p. 128; 29 Salmon, p. 787; 30 Lémery, p. 64; 31 William Cockburn, An account of the nature, causes, symptoms, and cure of the distempers that are incident to seafaring people, 1696, p. 25; 32 Salmon, p. 787; 33 Cockburn, p. 25; 34 Lémery, p. 64; 35 Gerard, p. 75; 36 Salmon, p. 787; 37 John Moyle, Abstractum chirurgiae marinae, 1686, p. 29; 38 Moyle, The Sea-Chirurgion, 1693, p. 23

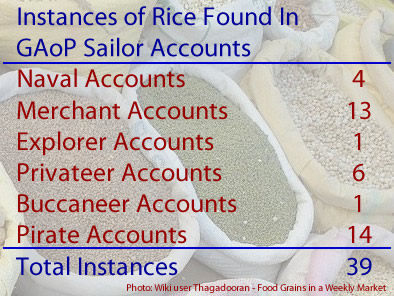

Rice

(Poaceae oryza sativa & glaberrima)

Called by Sailors: Rice

Appearance: 39 Times, in 23 Unique Ship Journeys from 30 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Alicante, Spain; Alexandria, Egypt; Madeira; Cape Verde Islands; Sherbro, Sierra Leone, Africa; Cape Palmas & Monrovia, Liberia; São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón; Mauritius; Ile Ste. Marie, Madagascar; Anjouan, Comoros Islands; Bally, Bengal, Goa, Mumbai & Rajpur, India; Nicobar Islands; Sri Lanka; Padang, West Sumatra; Banda Aceh, Buton Island, Halmahera, Jakarta, Palau Sinka, Siumpu Island & Sulawesi, Indonesia; Haiphong, Vietnam; Guam; Manzanillo, Mexico; Salvador, Brazil; Chesapeake Bay, Virginia;

Rice is the most mentioned food grain in the sailor's accounts, being found more than half as much again as the second most mentioned grain,

Photo: Sven Teschke - African Rice (Oryza Glabberima) with Bran

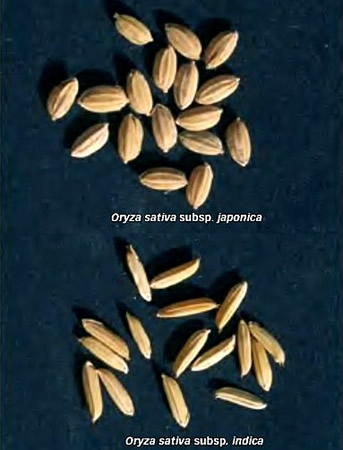

corn/maize. This is in part because it was native to two financially important trading locations during the period: Asia and Africa. Although the period authors do not recognize it, there are two types of cultivated rice: Asian rice (Poaceae oryza sativa) and African Rice (Poaceae oryza glaberrima). Asian rice began to be imported into Africa during the sixteenth century, although African rice remained predominate there, being sown throughout the upper Guinea Coast. "Slight morphological differences separate the two species of rice, making them difficult to tell apart in the field. Generally speaking, African rice has small grains that are pear-shaped and have a red bran and an olive-to-black seedcoat, straight panicles [multi-branched flowers] that are simply branched". African rice plants also have wider leaves which help prevent growth of weeds and are more tolerant to fluctuations in "water depth, iron toxicity, infertile soils, severe climates, and human neglect."2 Rice found in ships sailing in the Atlantic or at ports bordering it was almost certainly African Rice while that found in the Pacific was Asian Rice.

Rice is one of the grains given official sanction as a food to be used at sea along with wheat and oats. Unlike the other two grains, it was never anything but a substitute used when ships were sailing abroad. The 1677 Victualling contract specified that "all ships going to Guinea [Africa] or the East or West Indies... in lieu of a sized

Photo: Miquel Pujol Palol

Asian Rice Varieties (Oryza sativa indica and japonica)

fish, four pounds of Milan rice, or two stockfishes of at least 16 inches long"3.This was reiterated in the 1701 letter from the Admiralty to the Navy Board.4 This brings up two points of interest.

First, the rice was to be grown in the rice fields of Milan, presumably because they were closer to England than Africa or the East Indies and England was allied with the Holy Roman Empire during War of the League of Augsberg (1688-1697). Rice was brought to Sicily in the 13th century from Northern Africa5 meaning what was grown there was African rice (oryza glaberrima). Whether Milan was still sowing African rice in the seventeenth century is anyone's guess.

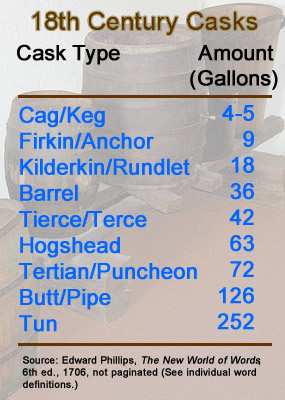

Second, four pounds of rice is a lot of rice. A cup of uncooked rice weighs about 7 ounces while a cup of cooked rice weighs about twice that - nearly a pound. So four pounds of cooked rice would be four cups while four pounds of uncooked rice would be unthinkable given that cooking it doubles its size and volume. It is likely they meant cooked rice, and even that seems excessive. Writing in 1671 (before any of these contracts were established) navy clerk John Baltharpe complained that Alicante, Spain, "A little Rice we get instead of Fish"6, which certainly doesn't sound like four pounds. It is possible that the navy meant four pounds to a mess, which consisted of four to six men who ate together. They were given one hot meal a day7, which would mean each man got one to two-thirds of a pound of rice.

The rice substitution was changed with the publishing in 1731 of the Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea, likely based on changes made some time after 1701. As explained in the entry for oats, fish had been entirely done away with on the navy menu by this time. The Regulations explained, "In case it shall be thought for the Service to alter any of the aforegoing Particulars of Provisions in Ships employed on Foreign Voyages, it is to be observed, that... half a Pound of Rice is equal to a Pint of Oatmeal"8. This amount seems more reasonable given how much rice someone could consume in a sitting.

Background Photo: Georges Jansoone

Although many sailors mention rice in their lists of food, most do not bother to describe it. There are some other details of interest found in their accounts. Several comment on how the rice was packaged. Like most dry foods, rice meant for ships typically came in barrels. Dampier mentions the Batchelor's Delight purchasing "Puncheons of Rice" on the African Guinea Coast in 1683.9 The merchant ship Adventure purchased "about a Tun and half of Rice" in Padang, West Sumatra in 1698.10 Pirate Stede Bonnet 'traded' "two Barrels of Rice" among other things with a merchant ship they captured in July of 1718 for salt beef and bacon.11

Some other methods of packaging the rice are found in the sailors accounts. When the buccaneer Cygnet stopped in Guam in May of 1686, the governor of the island sent "six or seven Packs of Rice"12. Edward Cooke, captain of the captured ship Marquis of Woodes Rogers' privateer fleet, reported that in March of 1710 they stopped at Guam as well where they purchased "60 Bags of Rice and Paddy [rice in the husk], at 2 Dol. per Bag"13. These were almost certainly large cloth sacks of dried rice. Speaking of prices, navy physician John Atkins reported that rice could be purchased at Cape Palmas, Liberia in 1721 for "about 2s. per Quintal [hundredweight]"14. He mentions that they would also trade it and other foods for "brass Pans, pewter Basins, Powder, Shot, old Chests, &c."15

Rice is one of the three grains found in pirate accounts, the other two being corn/maize and oats. Unlike the other two, it is found in more often than in any other the other sailor types except merchants. In addition to the Stede Bonnet reference cited above, rice is found in the accounts of East Indies pirates Dick Chivers, Edward Coates, Edward England, Henry Every, William

Port map -

From the Island of Ste. Marie 16 Lat S. (1733) - Bibliothèque nationale de France

Key:

A. Islet of the key (Small Island) B. Place where the rowboats go to the water C. Place where the

blacks go to water D. Jetty or pirates careening site.Z. Z. Sunken vessels forming a gate. Note that the

darker plus route is marked by 'B's, suggesting it's the route rowboats took to get water. The fort (purple)

was built by the French and abandoned in 1674. Although the details cannot be seen her, it contains

(from top clockwise): Chapel, Kitchen or Bathrooms (?), Magazine, Lodging, Jail and Hospital. It is

not known if the pirates made use of the remains of the fort.17

May, Thomas Moysten and Richard Glover and in account of Atlantic pirate Howell Davis.16 The Davis reference actually comes from a profile of western African islands São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón written by sea surgeon John Atkins for the General History, so while it is possible that Davis' crew might have eaten rice there, it is not certain. Even Bonnet, the other Atlantic-based pirate who mentioned having rice, was 'trading' the rice with a captured vessel in a token effort to justify taking their meat which was generally considered a more desirable food by sailors.

It is not at all surprising that rice would be a prevalent food to the other pirates listed, all of whom were sailing in the East Indies; rice was grown on Madagascar where Adam Baldridge had his trading fort in the late seventeenth century, a location where all of the pirates listed stopped at some point.

Although not counted in the above numbers, there is a connection between a sailor coming from Madagascar and the introduction of rice to the Carolinas by a former buccaneer surgeon.17 Sir John Yeamans was directed to explore 'Carolina' on behalf of the Lords Proprietors

Rice Cultivation on the Ogeechee River, SC, Harper's Weekly (1867)

(eight men who held a charter from Charles II). He sent Captain Robert Sanford to Port Royal (South Carolina) in July of 1666. Sanford decided to leave "an English man in their roome [the land of the Kiawah natives] for the mutuall learning their language, and to that purpose one of my Company Mr. Henry Woodward, a chirurgeon, had

before I sett out assured mee his resolucon to stay with the Indians if I should thinke convenient"17. The Spanish eventually learned of Woodward's presence, captured him and imprisoned him in St. Augustine.

Woodward was released from the Spanish prison by buccaneer Robert Searle during Searle's raid in 1667. Searle "took Dr. Woodward to the Leeward Islands, where he shipped as surgeon on a privateer in order to defray his expenses to England"18. The privateer Woodard was sailing aboard shipwrecked near Nevis in 1669. Woodward was picked up from Nevis by Joseph West, captain of a small fleet sailing from England to Carolina where they were establishing a new colony along the Ashley River. It is here that Madagascar rice enters the picture.

In 1731, a pamphlet concerning the financial importance of Carolina to the English explains,

The Production of Rice in Carolina, which is of such prodigious Advantage, was owing to the following Accident. A Brigantine from the lsland Madagascar happened to put in there; they had a little seed Rice left, not exceeding a Peck, or Quarter of a Bushel, which the Captain offered, and gave to a Gentleman of the Name of Woodward. From Part of this he had a very good Crop, but was ignorant for some years how to clean it.19

Unfortunately, this citation fails to establish the date this occurred, the name of the ship, its

A Brigantine, From Nouveau Voyage aux isles de l'Amerique, Vol. 2,

By Jean Baptiste Labat (1722)

captain or even Woodward's first name. In an Annual Review prepared by Charleston Mayor William Ashmead Courtenay in 1883, the mayor points out that an inventor was rewarded by an Act of Assembly in 1691 for a rice husking machine he created. Courtney suggests the machine's invention was "probably 1685, and the date of the earliest rice planting must have been previous [to that], and perhaps nearly coeval with the [Ashley River] settlement [in 1669]"20.

One current version of this story suggests that the captain who brought the rice was pirate trader John Thurber, who met Woodward when he put into Carolina in 1685 to have storm damage to his ship repaired.21 However, the earliest written account of this comes from a book written in 193722. 1685 may have been cribbed from Mayor Courtenay's suggestion that the rice husking machine 'probably' started being used then. As such, the best that can be said based on the data available is that some ship captain sailing from Madagascar gave a man named Woodward rice between 1669 and 1691 which may have started the rice boom in the Carolinas.

The one sailor to describe the rice plant was (not surprisingly) William Dampier, who found it in Tonquin (modern Haiphong, Vietnam) in 1688 while sailing with Captain Weldon on the East Indiaman Curtane.

Rice Plant, From The Herball or General Historie of Plantes,

By John Gerard (1636)

Here is good plenty of Rice, especially in the low Land., that is fatned by the overflowing Rivers. They have two crops every year, with great increase, if they have seasonable Rains and Floods. One Crop is in May and the other in November and tho the low Land is sometimes overflown with water in the time of Harvest, yet they matter it not, but gather the crop and fetch it home wet in their Canoas; and making the Rice fast in small bundles, hang it up on their Houses to dry. This serves them for Bread-corn and as the Country is very kindly for it, so their Inhabitants live chiefly of it.23

Keep in mind that 'corn' was used the English to refer to most grains.

Botanist John Gerard described rice as growing in "a certain mane or plume as Mill or Millet or rather like Panick (genus Panicum, often referred to as panicgrass)." He goes on to explain that at the top of the plant "groweth a bulb or tuft... garnished with round knobs like small goose-berries, wherein the seed or graine is contained: every such round knob hath one small rough aile, taile, or beard like unto Barly hanging thereat."24 This can be seen in the image sketched next to his description (at right). Gardener Joseph Miller explains that rice plants produce "loose Spikes, much divided, and compos'd of oblong flattish Grains,having each a Beard or Awn two or three Inches long, and forked at the Top, and frequently curl'd. at Bottom; they are of a white Colour, inclos'd in a brown Husk or Skin."25

The majority of the places where the sailors found rice were in the East Indies. Yet, by this time, it was grown all over the world. Physician William Salmon said "It grows now not only in [Middle Eastern Countries], but also in the Fortunate lslands or Azores, and in Italy and Spain, from whence great quantities have been brought to us, hull'd, and prepared, as we now Buy it... through all Æthiopia and Africa"26. We have already seen how the navy specified that their rice to be grown in Milan. Miller noted, "Rice is sown in Italy and Turkey and the East Indies; and we have as large and good from Carolina, as from any Part of the World."27 Salmon agrees, explaining "It is now Sown in Carolina, and become one of the great products of the Country: I have seen it grow, and flourish there, with a vast increase, it being absolutely the best Rice which grows upon the whole Earth, as being the weightiest, largest, cleanest and whitest, which has been yet seen in the Habitable World."28

As food, botanist Louis Lémery advises selecting "such Rice as is clean,

white, new, plump, hard, and swells when 'tis boiled."29 As Salmon's citation above suggests, size and color were considered important aspects of rice selection. Being a hot

A Tudor Trench and Table Setting

meal, rice would usually have been served for dinner on a navy ship and likely on merchant and other ships as well. However, the men of the merchant ship Rochester reportedly said in 1705 manuscript that after leaving Madagascar, they "were so well stockt that we could boil a little rice for breakfast if we had it of our own."30

Several sailors mention recipes for preparing rice. Navy clerk John Baltharpe's poem about the Mediterranean trip of HMS St. David explained how rice was substituted for fish at Alicante in August of 1670, "Which to you well is known, but a poor Dish: Except good Spice to put in it, you had, For with good Sauce, a Deal-board is not bad"31. (A 'Deal-board' is a pine board, probably referring here to a pine trencher, which could actually be a simple board, or something a little less likely to spill liquids (see left).32)

When buccaneer William Dampier was sailing on the East Indiaman Curtane near Bandah Aceh, Indonesia in 1689, he said, "My Food was Salt-fish broyled, and boyled Rice mixt with Tire. Tire is sold in the Streets there: 'tis thick sower milk."33 Merchant sailor Frances Rogers, who was aboard the Arabia in 1702, explained that they had caught two dolphins "which made us a most noble supper, they being the most delicate of fish, ...boiled (which way with a piece of pork and oatmeal or rice, they make good broth)"34. Physician William Salmon also suggests way to use rice, putting it in a broth, used to make a savory pudding (either by baking or boiling with other ingredients) or boiled until it dissolves into a "milk."35 Gerard says the English make

Photo: Sathya Vharathi Agri - Rice Plants

"a certain food or pottage" using rice and milk. He explains, "Many other good kinds of food is made with this kind of grain, as those that are skilfull in cookerie can tell."36

Humorally, Salmon says rice "is temperate in respect to heat or cold, and dry in the first Degree"37. Lémery notes that the Paracelsian principles are "much Oil, and an indifferent quantity of Salt." He also says that rice "is good at all times, and for Persons of any Age, whose Humours are too sharp, and much agitated"38. He adds that it thickens "the sharp Humours a little, by its viscous and gluey juice, and thereby allaying the over-violent Motion of them."39

As an aid to health, Joseph Miller comments, "It is more used for Food than Physic [medicine], being a wholesome strengthning Grain, restringent [restricting] and good for those who have a slipperiness in their Bowels, or are inclinable to a Flux or Looseness."40 The restringent character of rice is repeated by everyone, probably because, as Gerard points out, "Galen saith" it.41 Lémery says it "is softning... increases Seed, repairs and supplies the parts of the Body with good Nourishment, stops spitting of Blood, and is good for pthisical [tubercular] and consumptive Persons."42 Salmon concurs with the medicinal properties listed by the above authors. He also indicates that rice can be used to make a cataplasm or poultice "the Meal or Flower of Rice boiled with Milk to the Consistence of a Pultice: or it may be made of the whole Rice, boiled to softness in the Milk and then to a consistency, adding to it a little Barly Flower, It is best used to be applyed to Tumors to repel Humors flowing to them"43.

1 "The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Capt. John Quelch", A Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol. 14, 1700-1708, 1825, p. 1082; John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 59, 62, 63,152 & 256; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 54; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 83, 228, 361 & 372; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, Vol. 2, 1712, p. 9, 15, 42 & 43; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 78, 304 & 474; Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 22, 25, 30, 126 & 148; William Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 163; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 24; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 35, 101, 245 & 284; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 93; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 280; Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, ed., 1923, p. 167, 175, 182, 183 & 184; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 57, 98, 130, 188 & 446; John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 197; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 151; 2 Olga F. Linares, "African rice (Oryza glaberrima): History and future potential", PNAS (Proceedings of the National Acadamy of Sciences of the United States of America), Vol. 99, No. 25 (December 10, 2002), p. 16361; 3 J. R. Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution: Part II 1673-1679", The English Historical Review, Vol. XIII (1898), p. 32-3; 4 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 255; 5 Kate Springer, "Why You Should Eat Rice—Not Pasta—in Milan", Conde Nast Traveler, August 8, 2017, gathered from the internet 2/23/23; 6 Baltharpe, p. 54; 7 This is based on the account of Frenchman César de Saussure account of sailing on HMS Torrington in 1729. He says each mess of men was given a half pound of cheese and butter for breakfast and lunch and a hot meal for dinner. See César de Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 364; 8 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 61; 9 Dampier, 1699, p. 78; 10 “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 245; 11 “22. David Herriot and Ignatius Pell on Blackbeard and Stede Bonnet, from The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and other Pirates (London, 1719), pp. 44-48”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 101; 12 Dampier, 1699, p. 78; 13 Cooke, V2, p. 9; 14 Atkins, p. 62; 15 Atkins, p. 63; 16 Defoe (Charles Johnson), pp. 57, 98, 130 & 188; Fox, pp. 35 & 101; Jameson, pp. 167, 175, 182, 183 & 184; 17 Thanks to researcher Matt McLaine for suggesting this story to me; 18 Robert Sanford, "Being the Relation of a Voyage on the Coast of the Province of Carolina, formerly called Florida...", Shaftesbury Papers, Quoted in Narratives of early Carolina, 1650-1708, Alexander S. Salley Jr., ed., 1911, p. 104-5; 19 Alexander Sally, Introduction to "A Faithfull Relation of My Westoe Voiage, By Henry Wooward, 1674", Narratives of early Carolina, 1650-1708, 1911, p. 127; 20 Fayrer Hall, The Importance of the British Plantation, 1731, p. 18; 21 For example, see "Rice History", www.carolinaplantationrice.com, gathered 2/28/23; 22 "Carolina Gold rice... was grown from seed brought to the province of Carolina about the year 1685. The rice had been raised in Madagascar, and a brigantine sailing from that distant island happened, in distress, to put into the port of Charles Town. While his vessel was being repaired, its captain, John Thurber, made the acquaintance of some of the leading citizens of that town. Among them was Dr. Henry Woodward... To Woodward Captain Thurber gave a small quantty of rice - less, we are told, tha a bushel - which happened to be on his ship." (Duncan Clinch Heyward, Seed from Madagascar, 1937, p. 4); 23 "Sainte-Marie Island, Madagascar", archeologiedelapiraterie.fr, gathered 2/27/23; 24 John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 79; 25 Joseph Miller, Botanicum Officinale, 1721, p. 324-5; 26 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 943; 27 Miller, p. 324-5; 28 Salmon, p. 943; 29 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 63; 30 Earle, p. 91; 31 Baltharpe, p. 54; 32 Dampier, 1700, Part 1, p. 148; 33 Angela Dunsby, "The Humble Trencher", www.johnmooremuseum.com, gathered 2/28/23; 34 Rogers, p. 151; 35 Salmon, p. 943; 36 Gerard, p. 79; 37 Salmon, p. 943; 38 Lémery, p. 63; 39 Lémery, p. 64; 40 Miller, p. 325; 41 Gerard, p. 80; 42 Lémery, p. 63; 43 Salmon, p. 943-4

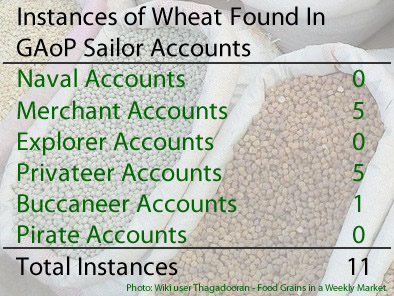

Wheat

(Poaceae Triticum)

Called by Sailors: 'Maccaroons', Wheat

Appearance: 11 Times, in 6 Unique Ship Journeys from 6 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Alexandria, Egypt; Oman, Africa; Surat, India; Mocha, Yemen; Guam; Barbadoes; Chileo Island, Coquimbo & Juan Fernandez Islands, Chile; Cerro Hoya Mountain, Panama;

Wheat is the third of three grains officially sanctioned by the English Navy. By the numbers, it doesn't appear to be a very important grain. Yet these numbers are misleading. If all the examples of bread found in the period sailor's accounts could be positively identified as wheat bread, there would easily be as many mentions of wheat grain as their are of rice. However, the sailors accounts typically only mention 'bread' or 'biscuit' in passing, so the makeup of these things cannot be identified with certainly. One exception come from the ever observant buccaneer William Dampier. When the Cygnet stopped at Guam in 1686 on the way to the East Indies, Dampier noted that the governor of the island sent them "a Jar of fine Rusk, or Bread of fine Wheat-Flower, baked like Bisket, but not so hard."2

It would probably be excusable to count instances of biscuit due to the naval instructions for the makeup of biscuit. The 1677 Victualling Contract states that every sailor was to daily receive "one pound avoirdupois of good, clean, sweet, sound, well bolted [well sifted] with a horse cloth,

A Piece of Ship's Biscuit (1784)

well baked and well conditioned wheaten biscuit'."3 As it happens, however, none of the naval sailors accounts included here specifically mention biscuit, even though we know it was a staple in the navy sailor's diet. It is likely that the biscuit purchased for most merchant, buccaneer and privateer voyages as well as that which was stolen by pirates was also wheat. Although these instances are not counted in the above numbers, there are 6 sailors accounts which mention biscuit.4

The navy made their own biscuit during this period, some at their London Tower Hill yard and some at the nearby Rotherhithe mills they leased for this purpose. They still had to buy the wheat to process. Paula K. Watson explains that during this period, “Wheat was usually bought [by the English Navy] in the winter and spring. In 1703/4 contracts were placed with eight dealers, but one of these, Francis Collins, had six contracts for 1,930 quarters (1/4 of a hundredweight). The rest delivered between 100 and 450 quarters.”5 Not everyone thought that the wheat purchased by the navy was of the best quality. In the pointedly critical 1700 book Remarks on the Present Condition of the Navy, the anonymous author says, "I could tell you also of another [vendor] that sells Wheat to the King, and far from being the best, at the best price; and of another that sells flower to the Office for Sea-Service, which after the Labourers have broken the Lumps in it, is bak'd into Coarse Bread."6

Perhaps the most notable thing about the sailor's accounts which mention wheat is

Artist: Peter Bruegel the Elder - The Harvesters (1565)

how often they mention the amount of of it they found in various locations. Captain Alexander Hamilton said that at Mocha, India "they have no Rice tho; Plenty of Barley and Wheat."7 While visiting what is today Oman, Africa, he mentioned that he found "good Markets for Wheat, Barley and Legumen"8. Buccaneer Basil Ringrose explained that there was "great store of Wheat, Barly, and all European Grain" in Coquimbo, Chile when the Trinity and May-flower stopped there in December of 1680.9 Privateer George Shelvocke indicated he found "a good quantity of wheat, barley, potatoes, maiz, or Indian corn" on a cattle ship they captured near Chileo Island, Chile and that "great quantities of wheat, flour, [and] bread" could be found in Trujillo, Peru.10 This repetition of large quantities of wheat being found in certain places is significant; sailors published their accounts because they knew other sailors would buy them to use as guides when they sailed in the same areas. Indicating where good food or water could be found helped to sell copies.

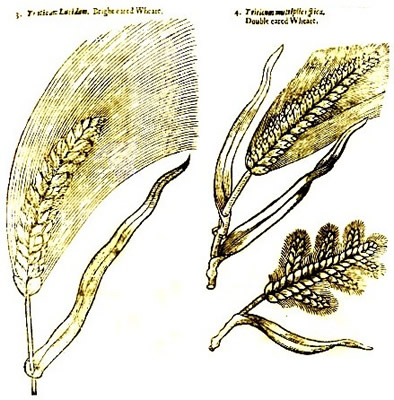

Since the sailors do not spend any time describing wheat, we must rely on the period botanists and physicians. Most of them suggest there are a variety of different types of wheat, each differing primarily in the appearance of the ear where the wheat grain kernels grow. Botanist John Gerard lists five different types, which are merged into four types of wheat by fellow botanist John Parkinson, who then adds three more.

Bright and Double Eared Wheats, From Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of

Plants, By John Parkinson (1640)

The first he calls Bare or Naked White Wheat, which "when it is full ripe, boweth downe the head a little with the weight thereof, and is set with two double rowes of seede or corne, wrapped up divers chaffie skins or cotes, and is when it is clensed of a firme compact substance, somewhat yellowish and cleare wlth all, and is the chiefest Wheate of all making the purest white bread."

Second is 'Bearded or red Wheate' which has a larger ear of a reddish cast with the grains more bent that white wheat appearing 'four square'. He dismisses the resulting bread as '"not so pure white".

Third is 'Bright eared Wheate' which has a bigger eare "a right browne blewish colour, long and rough, with beardes and aulnes [awns - hair or bristle like extensions], and the graine harder, and of a browner colour" which resulted in a clearly inferior "heavier and blacker bread." Gerard mentions that this type is "somewhat bright and shining".

Wheat of Candy, From Theatrum Botanicum the

Theater of Plants, By John Parkinson (1640)

Fourth is "Double eared Wheate' "which is shorter, and hath divers other small eares hung from the sides of the greater, the beards or aulnes are shorter and so is the graine it selfe is looser and lesse compact." The scientific name he gives this is 'Triticum multiplici spica'.

Fifth is 'wilde Wheate of Candy' which has ears that "are sornewhat rougher and blacker, the beardes also shorter, and the cornes lesser and blunt at one end, more like to Rie than Wheate.

Sixth is 'Tripoly Wheate', bought, not surprisingly, from Tripoly, "with broader leaves than our [English] Wheate, and eares an handfull long with very long beards, and blackish graines like. Rie within them."

Last, Parkinson lists summer wheat, which "hath narrower eares, longer beards, and smaller graines, and is onely to be sowne and reaped as Barley is with us, yet as it is earlier sowne in the warmer countries, so it will be the sooner ripe, but will not endure the coldnesse of our Winters."11

Parkinson goes on say that there are other varieties of wheat as well such as 'Duckes-bill' and cone wheat, but suggests that he isn't familiar with them and doesn't describe them..

Spelt Corn, From Botanologia - The English Herbal,

By William Salmon (1710)

Salmon divides wheats into three colors: white, red and grey. He then further divides red and white wheats by those with 'beards' or awls or those without. He says "Red Wheat... is accounted the finest and best of all wheat", but diplomatically goes on to add that "some will have [white wheats] to be the finest and best wheat of all; without a doubt, the difference between them is so little as not to be discerned."12. He suggests that grey wheat is the spelt corn of the ancients, of "which the Ancient Romans made to be a kind of Far, or Bread-corn, being a coarser kind of Wheat."13 His scientific name suggests that grey wheat is actually spelt wheat (Triticum spelta). Since they are very similar in appearance, it is not clear from the image he provides (seen at left) whether this grain is spelt wheat or not. (Compare this image with Parkinson's previous drawing of 'Brighte Wheate'.) Salmon describes grey wheat as being "almost the color of the Red Wheat, but much paler, the Corn [grain] itself being... plumper, or fuller and larger. The meal of this makes admirable good White Bread, Cakes &c. but it is scarcely so White as the others, nor yet so Sweet."14

He finishes his discussion of wheats with a another type, which he indicates is a variant of red wheat that sounds like the same type as Parkinson's 'Double Eared Wheate'.

Given all these various types of wheat, it is worth looking at the wheats that are

recognized today which have been classified based on genetic research rather than the appearance of the grain. These include 1)

Photo: Matt Lavin - Ears of Triticum Aestivum in a Field

Triticum monococcum or einkorn wheat, which is no longer produced, being more in use during medieval times, 2) Triticum urartu, which was not cultivated and therefore is not likely to have been mentioned by the period authors as an edible wheat, 3) Triticum turgidum which include emmer wheat, durum wheat, and several other cultivated forms, 4) Triticum timopheevi, which is found only in the country of Georgia and so would not be mentioned by English authors and 5) Triticum aestivum, which includes modern bread wheat and spelt.15 "Practically all modern wheat cultivars belong to two species: (i) bread wheat, Triticum aestivuna... valued for the baking of high rising bread, and (ii) hard or durum-type wheat T. turgidum... used for the preparation of macaroni and low rising bread."16 Note that the color of the ears and the appearance of 'beards' or awls, is irrelevant. Since the focus of the period botanists and physicians was making bread, they are most likely all types of Triticum aestivum.

Gardener Joseph Miller advises that wheat "is more used for Food than Medicine"17. Botanist Louis Lémery says "Wheat ...makes the best Bread, and is most in use. ...you ought to choose that that is clean, dry, heavy, and plump." He goes on to explain how it is prepared for use: "[L]ay it by for some time before 'tis used; that so it may sweat out a kind of moisture that is in it"18.

Physician Salmon gives the most extensive list of recipes for wheat. He says that it can be used "to make Bread, Cakes, Puddings, Pultage, Panada, Frummery... Leven, Wafers, Gelly... &c." Wheat flour was brought

Wheat Flour

on navy ship voyages during the golden age of piracy to make puddings using peas or raisins, among other things. Salmon either making puddings with wheat flour, milk and eggs, or "If they are made of pure White Bread, they will be yet pleasanter". Ships would not have had much milk or eggs so would have used water to make their puddings. Pultage is wheat flour combined with water, primarily used as a medicine in the botanists books from the period. "Panada or Pap... is made with Water, Milk and Water, and sometimes with Milk alone with the finest White Bread, and chiefly for Infants and Children"19. Dictionaries from around the time define it as "a sort of gruel"20, "meat [food] made of Crums of Bread and Currants boiled"21 and "Food or thick Gruel made by boiling Bread in Water till it is brought almost to a Paste... being sweetened with Sugar"22. Frummery is wheat flour and water boiled, put into a container and cooled to form a solid mass. Leven was made by fermenting bread dough "and being made up into a round flat Ball, it is kept in a heap of Table or Bay Salt poudered, till it grows sowre, which you may know both by the Smell and Taste." Salmon refers to wafers as 'Sweet-Meat [candy] Wafers which he doesn't describe, only noting that they can be bought at "Confectioners, made up into small white Rouls." The jelly is made by boiling these wafers until they are the proper consistancy.23

The second type of wheat recognized today, durum wheat, is mentioned in the form of pasta, which was originally called itriyya. This wheat was known in Italy as 'hard grain'.24 Although pasta is often associated with Italy, it did

Artist: Johann Bernard Fischer von Erlach - Alexandria Port & Pharos Lighthouse (1721) not originate there; it was brought to Sicily during the Muslim occupation in the 9th through 11th centuries. "A medical text in Arabic written by a Jewish doctor living in Tunisia (North Africa) in the early 900s explains that... itriyya already meant long thin strands of dried dough that were cooked by boiling."25 The first written reference to dried pasta in Sicily appears in A Diversion for the Man Longing to Travel to Far-Off Places written by al-Sharif al-Idrisi in 1154: ’West of Termini [Termini Imerese, Sicily] there is a delightful settlement called Trabia. Its ever-flowing streams propel a number of mills. Here there are vast quantities of itriyya which is exported everywhere: to Calabria, to Muslim and Christian countries. Very many shiploads are sent."26 Being a dry food which was cooked by boiling, pasta would have made good food on ships. Some historians argue that pasta took hold in Italy "because it made such a good food for sailors, that it was a fuel for the ‘commercial revolution’ then overtaking Italian ports."27 However, it is not Italy, but the North African connection that is relevant here. There is only 1 instance of pasta in the period sailor's accounts, counted here because it was made from wheat. The merchant vessel Viner Frigott was traveling around the Mediterranean in the late 1670s when she stopped at Alexandria, Egypt where she was resupplied. Among the many foods purchased 'for sea store' was 'maccaroons', which modern historian Peter Earle translates as macaroni.28

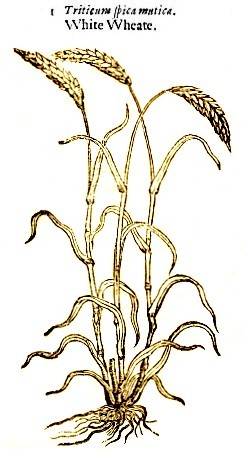

Humorally, Salmon says wheat is "temperate in respect of heat or cold, driness or moisture"29. Parkinson cites Galen as stating that "Wheate is in the first degree of heate, but neither drieth nor moisteneth evidently, yet Pliny saith it drieth."30 Gerard doesn't indicate the

'White Wheat Plant', From The Herball or General

Historie of Plantes, By John Gerard (1636)

general humoral effect of wheat, but does state, "Wheat as it is a medicine outwardly applied, is hot in the first degree, yet can it not manifestly either dry or moisten."31 This agrees with Galen's assessment. Lémery lists the Paracelsian principles of wheat as containing "much Oil and essential Salt"32.

Just about everyone who comments on the medicinal qualities of wheat agrees that it is a good ingredient for emplasters or poultices. Salmon says that wheat flour alone, "Outwardly applyed to Simple Wounds newly made, in a large quantity... presently stops the Flux of Blood"33. Other wheat flour-based plasters take various forms. Miller explains that wheat "boil'd ' in Milk, eases Pains, and ripens Tumours and Imposthumations [pus filled absesses]"34. Gerard quotes Diocoredes' recommendation that unripe green wheat "being chewed and applied, it doth cure the biting of mad dogs." Similar to Miller, he also recommends "The floure of wheat being boiled with hony and water, or with oyle and water, taketh away all inflammations, or hot swellings."35 Parkinson says, "the flower of Wheate mixed with the juice of Henbane doth stay the flux of humors to the joynts being layd thereon"36. There are a variety of other suggested plasters in the botanists and physicians book using preparations of wheat flour as a base, each having some degree of drawing or draining property.

Consumption of wheat gets mixed reviews. Parkinson cites Dioscoredes' warning that consumption of unripe (green) wheat "is hurtfull to the stomacke and breedeth wormes"37. Salmon says that wheat flour pultage "is good to strengthen the Stomach and Bowels; it nourishes very well, and stops Fluxes of the Belly." Wheat panada, he said, "absorbs the Watery humor in the Stomach and Bowels, and is prevalent against Fluxes of the Belly."38 He attributes similar drying and absorbent properties to wheat starch and wafers. The jelly is particularly useful, being "good against Spitting of Bloud, Coughs, Colds, Hoarseness and the like, being daily eaten."39

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 312; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 303; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 52, 68 & 144; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 41; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 94, 100, 207 & 371; 2 Dampier, 1699, p. 303; 3 Brian Laverly, The Arming and Fiting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 189; 4 Thomas Bowrey (merchant ship), The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 194; Johann Dietz (merchant vessel), Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 128; Peter Earle (merchant vessel), Sailors: English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 89; Charles Johnson (pirate vessel), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 297; Jean-Baptiste Labat (pirate vessel), The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 197; Ravaneau de Lussan (buccaneer vessel), The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 402; 5 Paula K. Watson, “The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714”, University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 107; 6 A Sailor, Remarks on the Present Condition of the Navy, 1700, p. 19; 7 Hamilton, p. 52; 8 Hamilton, p. 52; 9 Ringrose, p. 41; 10 Shelvocke, pp. 41 & 426; 11 See John Parkinson, Theatrum Botanicum the Theater of Plants, 1640, p. 1119 - 1121 & John Gerard, The Herball or General Historie of Plantes, 2nd ed, 1636, p. 65;12 William Salmon, Botanologia - The English Herbal, 1710, Book 2, p. 1248-9; 13 Salmon, p. 1249; 14 Salmon, p. 1250; 15 Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, 2000, p. 20-1; 16 Zohary and Hopf, p. 20; 17 Joseph Miller, Botanicum Officinale, 1721, p. 443; 18 Louis Lémery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 70; 19 Salmon, p. 1251; 20 Nathan Bailey, 'Panado", Universal etymological English dictionary 1724, not paginated; 21 Elisha Coles, "Panada", An English Dictionary, 1717, not paginated; 22 Thomas Dyche and William Pardon, "Panada", A New General English Dictionary, 1735, not paginated; 23 Salmon, p. 1252; 24 John Dickie, Delizia: The Epic History of the Italians and Their Food, 2008, p. 21; 25 Dickie, p. 21-2; 26 Dickie, p. 21; 27 Dickie, p. 28; 28 Earle, p. 89;29 Salmon, p. 1251; 30 Parkinson, p. 1122; 31 Gerard, p. 66; 32 Lémery, p. 70; 33 Salmon, p. 1251; 34 Miller, p. 443; 35 Gerard, p. 66; 36 Parkinson, p. 1123; 37 Parkinson, p. 1122; 38 Salmon, p. 1251; 39 Salmon, p. 1252