Cereal Grains in Sailors Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Cereal Grains in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 1

Cereal grains were well suited to ships at sea with the advantage over other plant-based foods (fruits and vegetables) of being able to be kept for long periods without rotting provided they weren't damaged by water or parasites. In addition, grains were an appropriate food for hardworking sailors. The nutritional value of cereal grains "is generally high... In most cereals the kernels are packed with starch, and in some, such as in wheats or oats, they also contain an appreciable amount of protein."1

Three cereal

Rice Chaff

grains were a part of the standard English naval diet for ships at sea for long periods during the golden age of piracy: oats (in the form of oatmeal), rice, and wheat (in the form of bread, specifically 'biscuit'). However, wheat was the only grain in the official naval diet at the beginning of the golden age of piracy; the others were considered location-dependant substitutes. Once a ship left England, the 'standard' food was replaced by substitutes according to what was available to the ship in foreign locations. After 1678, English naval vessels headed to the East or West Indies or Africa could substitute "four pounds of Milan rice"2 for the fish normally served on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday. In addition, a pound of 'rusk', (twice-baked bread, something English sea biscuit was technically not), "of equal fineness [referring to the finely sifted wheat flour]", could likewise be substituted for a pound of biscuit on ships headed for the same places.3 This would simply have been a substitute of one wheat product for another. The third grain appeared in the navy's list of sanctioned foods for use at sea beginning in 1691. As a result of the order, "oatmeal could be issued in lieu of fish, 1 gallon of oatmeal being reckoned equivalent to 1 cod."4 It had replaced fish in the standard menu by 1703.

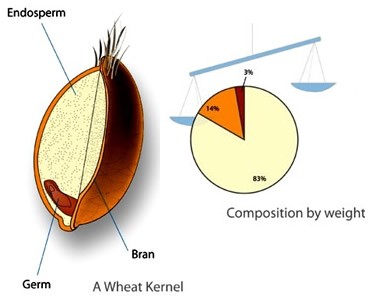

Before proceeding the nature of cereal grains should be understood. When harvested, cereal grains (those produced by grasses) have a dry, scaly protective covering called chaff which is indigestible to humans. This chaff must be loosened by milling or pounding the grains (threshing). Once loosened, the chaff can be removed by winnowing - repeatedly tossing it into a light breeze.

Artist: Jon Chui - Parts of a Wheat Grain Kernel

After the inedible chaff is removed, cereal grains primarily consists of three parts: bran, endosperm and germ. Bran is the edible outer layer of a cereal grain which is typically darker colored. It is-a shade of brown in barley, oats, rice and wheat, yellow in corn and a variety of colors - white, grey, yellow, red and brown - in millet. Bran contains a great deal of fiber along with "antioxidants, B vitamins, minerals like zinc, iron, magnesium, and phytochemicals — natural chemical compounds found in plants that have been linked to disease prevention."5 The endosperm makes up the majority of a grain, providing food to the plant that grows from the seed. It has an off-white color. It contains starches (carbohydrates), proteins and some healthy vitamins and minerals. However, it has far fewer vitamins than either bran or endosperm. The germ, or embryo is at the center of the grain which is where the growth of a new plant comes from. Like bran, it is generally darker colored. It contains vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and proteins. It also contains polyunsaturated fats which oxidize and become rancid when stored, so its presence causes the grain to go bad, limiting the usefulness of flour on long-voyage ships.

Before cereal grains are consumed, they are processed into flour. This was done by stone grinding. The flour was then used to make bread, biscuit or rusk, all of which were found on ships. Flour could also be used to make English puddings, something regularly eaten on English naval vessels. The most familiar type of flour to most people today is whitened wheat flour, although other cereal grain flours such as rye, oat, corn and barley flours have gained some notoriety in recent years.

Although the focus in this article is on the cereal grain flours, there are some other, non-grain fruits and vegetables which can be processed into a type of flour. These include bananas, beans, chickpeas and potatoes, each of which were mentioned in the accounts as being a substitute for bread in some sailors accounts.

Artist: Jan and Caspar Luyken

De Grutter (Grocer), Sacks of Meal in the Foreground, Mill in the Back

From Vertoond in 100 verbeeldingen (1694)

Vegetable starches were frequently used by natives in the East and West Indies during the golden age of piracy including Cassava Root and Sago Pith. These fascinated (and sometimes fed) English sailors. Still other plants could provide flour substitutes as explained in the articles which can be read by following the links.

Although the bran and germ are the healthiest parts of a grain, great esteem was placed on white flour throughout history including this period, so both the bran and germ had to be removed to create the 'best' flour. Whiter flours required much more stone milling and processing.

'Low grinding' was the unsifted flour from a single pass through the millstones. This flour had a 100% extraction, meaning it contained all parts of the original grain. This flour made dark hearty bread that retained all of the original nutrients of the grain. However, the whiter grades of flour were always more desirable to the higher classes and they were therefore more expensive. 'High grinding' was flour that had been reground multiple times and sifted extensively to remove the bran. Ironically, the flour consumed by the upper classes, who could have eaten the very best, was the less nutritious flour that had the bran and germ taken out.6

It was the last type of flour required by the navy according to the 1677 Victualling Contract. It specified that the wheat flour used to make biscuit for navy sailors was to be "good, clean, sweet, sound, well-bolted [well-sifted] with a horse cloth [a horse hair sieve]"8.

1 Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, 2000, p. 16; 2 J. R. Tanner, "The Administration of the Navy from the Restoration to the Revolution: Part II 1673-1679", The English Historical Review, Vol. XIII (1898), p. 33; 3 Tanner, p. 32; 4 R.D. Merriman, The Sergison Papers, (Naval Clerk of Acts), 1950, p. 236; 5 Emma Orchardson, "Whole grains: What they are, why they are important for your health, and how to identify them", www.cimmyt.org, gathered 2/1/23; "Anatomy of Rice", riceland.com, gathered 2/1/23; 6 Heather Wight, "The History and Processes of Milling", resilence.org, gathered 2/2/23; 7 J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 166

Cereal Grains Found In Sailors' Accounts

The number

Image Artist: Pietro da Cortona - Landscape with Harvesting (1750)

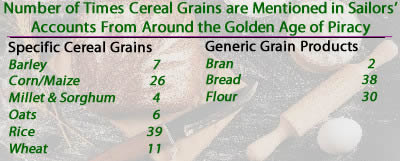

of specifically named cereal grains found in the period sailor's accounts is 61, which is a relatively large number given how many generic grains the English would have been familiar with. Since cereal grains required processing to be edible, when they are found in the period sailor's accounts as food, they are often mentioned in their processed state. Oats appear as oatmeal, wheat as wheat flour and so on. Where the type of grain is specifically identified, they have been counted in the tally for that specific grain.

In addition, there are 3 cereal-grain-based foods which are often mentioned without specifying the type of cereal grain used to make them.2 These include the all-important naval staples of bread and flour as well as bran. These non-specific processed grain products are most likely wheat-based. Yet, without further description, this is not assumed here and these instances are counted separately from processed food for which the grain used is specifically identified.

Given that the navy relied on well-baked bread and oatmeal to feed their men and most (if not all) sailors served at one time or another in the navy during their career, it should not be surprising that there are a lot of mentions of grains and grain-based foods in the sailor accounts. In all, thirty-six different sailors' accounts mention cereal grains or their products during the voyages described.

Each entry for individual cereal grain mentioned in this article first gives a common name for the grain followed by the genus and species in parenthesis. The entry then indicates any names(s) given to the grain in the sailor's accounts,

Background Photo: Rye Bread with Flour and Egg

the number of times that grain appears in the various sailor accounts under study, the number of different accounts and the number of different ship's journeys in which it appears (some authors accounts present journeys on a several ships, so there can be overlap.) A chart is also included showing which types of sailor's accounts mention the grain.

The main body of the text includes a period description of the grain, providing any details of the taste and preparation of the cereal grains found in books from that time. For most grains, many of the sailor's books simply mention the name of the grain found without providing any detail about its flavor or use. In such cases, information is taken from other sources. The emphasis in this article is on the period descriptions and understanding of grains. In the rare instances where period descriptions are lacking or incomplete, modern descriptions are used.

Artist: Albert Anker

Hippocrates Composite Portrait

Paracelsus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus

von Hohenheim (1455)

Since this website concerns medicine, some information on humoral properties originally suggested in the works of Hippocrates. He identified four humoral properties present in nearly everything including foods. This was expanded upon by some of his later followers, particularly Galen of Pergamon The four properties associated with food include hot, cold, moist and dry. According to the primary medical theory in use during this period, the humoral properties of food combined with a patient's own humoral makeup (affecting the body's humoral fluids blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile) impacting the patient's health.

One botanical author regularly used in this article - Louis Lémery - relies upon the three Paracelsian principles instead of humors. These principles include salt, which composes the solid state of a body; sulfur, responsible for an inflammable or fatty state; and mercury, engendering a smoky (vaporous) or fluid state.3 The translation of Lémery's work uses the terms salt, oil and phlegm, with phlegm apparently corresponding to mercury.

Photo: Miquel Pujol

Various Cultivated Cereal Grains - (From Top Left)

1) Pearl Millet, Rice, Barley, Oats,

2) Sorghum, Maize, 3) Millet, Wheat, Rye, Tritcal

Finally, specific comments of interest about the medicinal or healing properties of a cereal grain are given. While these sometimes tie directly into the humoral theory (more often, indirectly), sea surgeons would typically be a little less interested in these theoretical connections than physicians; surgeons would be more interested in a grain's impact on a patient's health.

For ease of reference, the specific cereal grains can be directly accessed in the list below. Clicking on the grain will take you directly to the information for it. The non-specific processed cereal grain-based foods discussed in the sailor's accounts follow the specific grains. Given the English preference for wheat bread and flower, most (if not all) of these are likely wheat-based products. Since this cannot be determined from the text, however, they have been given their own section as mentioned.

Specific Cereal Grains Found in Sailors' Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | Corn/Maize | Millet & Sorghum | Oats |

| Rice | Wheat |

Processed Cereal Grain-Based Food Found in Sailors' Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy |

|

| Bran | Bread | Flour |

1 "The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Capt. John Quelch", A Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol. 14, 1700-1708, 1825, p. 1082; John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 59, 62 & 152; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 54; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 74, 83, 228, 312, 361 & 372; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 194-5; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V2, 1712, p. 9, 15, 43 & 68; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 78, 303 & 474; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 22 & 126;William Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 128; William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, Vol III, 1703, p. 150 & 163; Jonathan Dickenson, God's Protecting Providence, 1700, p. 49; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 128; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 63; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 24; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 35, 101, 245 & 284; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 316; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 93 & 150; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 52, 68, 144, 280, 353 & 439; John Franklin Jameson, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, 1923, p. 182, 183 & 184; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 57, 98, 130, 183, 188, 215 & 446; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 197; Ravaneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 336, 415 & 460; Pyrates Lately taken by Captain OGLE", 1723, p. 70; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 20 & 41; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 26; Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal of His Expedition", A Collection of Original Voyages, William Hacke, 1699, p. 43; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 94, 100, 189, 268, 300 & 426; The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, 1719, p. 19; 2 "The Arraignment, Tryal and Condemnation of Capt. John Quelch", A Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol. 14, 1700-1708, 1825, p. 1082; John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 14 & 73; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 270; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 194-5; Edward Cooke, A Voyage to the South Sea and Round the World, V1, 1712, p. 60 & 324; John Covel, Diary, Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 115; Ambrose Cowley, A Collection of original voyage, William Hack, Ed., 1699; CSPC America and West Indies, vol. 12, Item 1406; Daily Courant, 8-8-22, Issue 6489; William Dampier, "Part 2", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 18 & 38; Jonathan Dickenson, God's Protecting Providence, 1700, p. 49; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 128; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 60; Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 97; Peter Earle, Sailors English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, 1998, p. 88 & 89; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 23, 25, 99, 106, 177 & 255; Amedee-Francois Frezier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 75; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 93 & 247; The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., November, 1919, p. 205; The Indian Antiquary, George Hill, ed., January, 1920, p. 3; John Franklin Jameson, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period – Illustrative Documents, 1923, p. 294; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 98 & 297; Ravaneau de Lussan, The History of the Buccaneers of America, 1856, p. 402; Stephen Martin-Leake, The Life of Sir John Leake, 1920, p. 222; Pyrates Lately taken by Captain OGLE", 1723, p. iv; Basil Ringrose, The Adventures of Capt. Barth. Sharp, And Others, in the South Sea, 1684, p. 26; Jeremy Roch, "The Diaries of Jeremy Roch", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 127; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 100, 189, 371 & 426; Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, 1825, p. 144 & 200; Silas Told, An Account of the Life, and Dealings of God with Silas Told &c., 1786, p. 14-5; 3 "From Alchemy to Chemistry: Five Hundred Years of Rare and Interesting Books", illinois.edu website, gathered 7/28/22;