Eggs and Dairy in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Animal Products in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 3

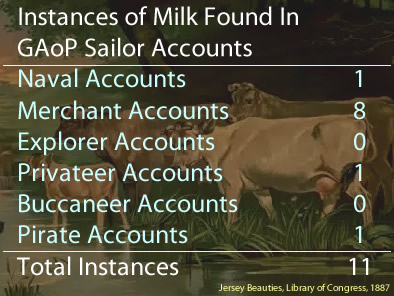

Milk

Called by Sailors: Milk

Appearance: 11 Times, in 11 Unique Ship Journeys from 10 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Bergen, Norway; Bruges, Belgium; Fomentera, Spain; Tunis, Tunisia; Iraq; Mauritius; Bandah Aceh, Indonesia; Iceland; James Valley, St. Helena; Juan Fernandez, Chile; Diafara, Panama;

Being the source of all dairy products, some of the historical aspects of the the industrialization of milking and suggestions by some authors of the period for judging effective cows and their pastures was previously discussed in the section on dairy.

Of the three dairy products found in sailor's accounts during the golden age of piracy, milk is the least mentioned. This is not surprising given that 1) it

Artist: Johannes Vermeer - The Milkmaid (c. 1658)

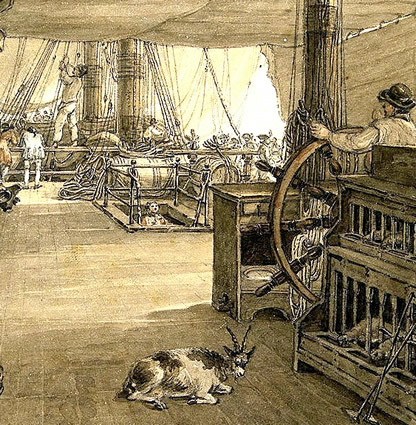

would have been the most difficult dairy product to keep from spoiling added and 2) the other two dairy products were standard issue by the English Navy and would have been familiar to, and likely an expected part of a shipboard diet by sailors. Nearly every instance of milk found in the sailor's accounts takes place when the author had made landfall. The one exception comes from pastor Henry Teonge's account of HMS Royal Oak sitting in the harbor of Mahon, Spain in March of 1679. He reported that "A Spanyard coming on board to sell milke" had not managed to get off the ship before she left and "was forced to goe alonge with us" to Formentera.2 It is notable in that it suggests that enough sailors enjoyed drinking milk that it was worth the effort of those selling to sailors stuck aboard a ship in port. Such vendors would have focused on foods desired by sailors stuck shipboard. The fact that ten different accounts mention milk as food also hints at it having at least some popularity among sailors.

With two exceptions, the milk mentioned in the sailor's accounts was most likely cow's milk. In fairness, 6 of the accounts do not specifically state that this is the case although two mention 'cattle' in the same sentence3. However, it is the type of milk which would have been what was most familiar to an English sailor. Of the remaining accounts, 3 specifically state that it is milk from cattle4, one mentions goat's milk5 and the other reindeer milk6. Of course, being world travelers, it cannot be certain what sort of animal milk the sailors were talking about when they simply mention the word without any further context.

The account of goat's milk is perhaps the most interesting because it gives a little detail as well as portraying the ingenuity of sailors. It comes from a second-hand story written by William Funnell regarding a group of French pirates who sailed to Juan Fernandez Island

The Author Milking a Goat in Period Garb, Brigand's Grove Event, 2011

after encountering bad luck and and too many Spanish sailors during their cruize of the western South and Central American coasts probably in the mid or late 17th century. He explains that there were twenty of them who decided to stay on the island for almost a year. Juan Fernandez had been stocked with goats by the Spanish in the 15th century. During the nine or ten months the French pirates were on the island, they tamed some of the goats so that "many of them come of themselves to be milked; of which Milk they made good Butter and Cheese."7

The physicians had some thoughts on which type of animal milk was best. Writing in the late 14th century, Italian physician Castor Durante ordered the milk of various animals by its healthiness. This appears in the English edition translated by John Chamberlain in 1689. "The most precious Milk is the Womans; the second, Asses Milk; the third, Sheeps Milk; the fourth, Goats; and the last Cows Milk."8 Being a physician, his concern was health-oriented which impacted the ordering of the various milks he listed. Donkey's (asses) milk was considered a remedy by no less than Hippocrates who prescribed it for liver problems, edemas, nosebleeds, poisoning, fevers and to heal sores. Interestingly, modern researchers have found that donkey milk contains more lactoferrin than cow's milk which inhibits the growth of iron-dependent bacteria in the intestines and protects against viral diseases. The highest amount of lactoferin is found in human milk.9

Seventeenth century English physician Tobias Venner had a different take on milk from various animals, basing his observations on which type was best on the nature and healthiness of the patient.

Milking a Ewe, Cosmographie Universelle of Munster, 1875, facimile of 1549

But of Milk, there is great difference according to the kinds of it. Cowes milk for sound and full bodies is best, for it is fattest and thickest [the most viscous], and, consequently, of most nourishment: next unto it; for grossenesse [of a similar viscosity], is Sheepes milk. But for bodies that are with long sicknesse extenuated; or are in a consumption; womans milk is best; because it is most familiar unto mans body, and even of like nature. And. next unto it is Goats milk, because it is of meane [less viscous] consistence; for it is not so fat and thick as Cowes milk, and therefore breedeth not obstructions in the entrals as that doth; nor so thin as Asses Milk, which also in consumptions is much commended: wherefore the nourishment which it maketh, is of a middle nature betweene them both, exceeding wholsome and good. But Asses milk appertaineth rather unto physick [medicine] than unto meat [food], for it is of a thin and watrish substance, of a penetrating, cooling, and detersive [cleansing] faculty, by reason whereof, it is of singular efficacy in consumptions of the Lungs.10

French physician Louis Lemery wrote, “Goat's-Milk does not contain as much of the serous part as that of an Ass, and suits Persons of a moist [humoral] Constitution better than any other. It's a little astringent, because the Goat usually brouzes upon the Sprigs of Oak, Lentils, Turpentine, and several other astringent Plants, which communicate the same Nature to its Milk."11 Like medicine today, opinions varied on what sort of milk was best for health during this period.

Little is said of the process of milking animals other than cattle in the English husbandry books from around this period although what is said of milking cows would almost certainly apply to others. Seventeenth century commenters talk about the proper time for milking cows. In her book written for women, Hannah Glasse says, "The best and most commended howers [hours] for milking, are Indeed but two in the day, that in the spring and summer time which is the best season for the dairy, is betwixt five and sixe in the

Artist: Gerard ter Borch -

Maid Milking Cows (17th Century)

morning, and sixe and seven a clocke in the evening"12. This follows the advice of a previous author of a book for housewives by Gervase Markham, who is a bit more expansive on the topic, advising that it was better to milk twice a day and get good milk than three times resulting in bad milk.

Markham provides a detailed explanation of how the process is to be performed:

in the milking of a Cow, the woman must sit on the neere side of the Cow, she must gently at the first handle and stretch her dugges [teats], and moisten them with milke that they may yield out in the milke the better and with lesse paine: she shall not settle her selfe to milke, nor fixe her paile firme to the ground till she see the cowe stand sure and firme, but be ready upon any motion of the Cow to save her paile from overturning; when she seeth all things answerable to her desire, she shall then milke the cow boldly, & not leave stretching and straining of her teats till not one drop of milke more will come from them, for the worst poynt of House-wifery that can be, is to leave a Cowe half milkt; for besides the losse of the milke, it is the onely way to make a cowe dry and utterly unprofitable for the Dairy: the milke-mayd whilst she is in milking, shall doe nothing rashly or suddenly about the cowe, which may affright or alarrme her, but as she came gently, so with all gentlenesse she shall depart.13

As mentioned in the section on dairy, there was an increasing push towards the industrialzed milking of cows and away from the small farm model which relied primarily on the farmer's wife during the later half of the 17th century. By 1717, Aaron Hill's proposed plain for a large-scale dairy recommended building eight cow sheds to house fifty cows, each fed on new mown

Milking Shed at 12 oclock, From A Day at a London Dairy,

Knights Penny Magazine, July 31, 1841, p 297

sainfoin. A man would be appointed to mow the hay and oversee each cow shed. Quarters would house him and five milkmaids.Hill also gives details of an interesting plumbing system designed to direct the milk into vats where it could be churned (by trained dogs!) to produce butter and buttermilk. Whether such a thing was actually built or not, the design shows how, in less than forty years, the English mind had turned from small, 'Gentlewoman'-run, country estate dairies to something on a large, industrial scale focusing on efficiency and profitability.14

Without efficient refrigeration, the issue of spoilage was ever present. This is likely the main reason it wasn't usually found on ships unless the officers had brought a cow aboard to provide it. French physicians Charles Stevens and John Libault say that fresh milk shouldn't be kept for more than a day, particularly in the spring and fall "because of the heat and temperature of

Artist: Thomas Hearne

Livestock on the HMS Deal Castle, Captain J. Cumming in a voyage from the

West Indies

in the Year 1775 (1804)

the time woulde be spoiled and presently turned", although in the winter the cooler temperatures will allow it to thicken and keep longer. However, he also points out that milk can be put "in a place where it may be warme, to the end it may be kept the longer, and become the thicker in short time: inasmuch as heate doth savegard and thicken the milke, as cold doth sowre it and make it to turne by and by: and therefore to avoide this danger it is good to boile it: and thereupon to stirre it much before you let it sett, if peradventure you be not disposed to keepe it three daies or somwhat more."16 Presumably, he is suggesting that quick heating followed by cooling made the milk thicker so that it could last longer.

Stevens and Liebalt do explain how to tell good milk from bad. This is done by examining its "whitenes, pleasant smell, sweete taste, and reasonable thicknes in substance, in such sort as that being dropped upon ones naile it runneth not off presently, but staieth there and abideth round a good while"17. French physician Lemery generally agrees with Stevens and Liebalt, stating that good milk is "white, of a midling Consistence, good smell, and whose taste ought to be altogether free from. any thing that is harsh, bitter, sharp, or brackish. Lastly, it should be such as is new milked from an Animal that is neither too young nor too old, but such as are Healthy, Fat, and fed with good Food."18

Polish physician John Johnston explains that the best milk "is luke warm, of equal substance, put upon the Naile, it does not soon run off, light rather than heavy, not clammy but sweet, without smel, white and in some sort shining, finally which proceeds from an healthy Creature, being made in wel constituted Udders."19

It was widely agreed that the food that an animal ate affected the flavor of its milk as Lemery suggests in the previous quote. This and the age of the animal were both felt to affect the quality of the milk they produced. As Lemery elsewhere explains,

Artist: Adriaen van de Velde

Milk Cows and Sheep (1st Half of 17th Century)

The Milk of each Animal is more or less wholesome, according to the difference of Seasons. It's more serous, not so thick, and easier of Digestion, in the Spring and Summer, than at any other time; and the reason is, because the Animal then lives upon moister and more juicy Foods: The same may be also said of the Milk of each Animal, in respect to their different Ages; In short, when the Animal is in its Prime, its Milk is better, riper (as I may say) and easier of Digestion, than when 'tis either too young or too old; for in its first State 'tis too raw, and too serous, and in the last too dry, not so creamy, and hath fewer Spirits.20

Johnston notes that milk from lean animals 'nourishes little' and from fat animals "is apt to breed convulsive fits." He adds that the milk of "black beasts... is better than that of such as are white" and recommends against drinking the milk of a cow which has recently given birth because it "is most liquid and thin"21.

Looking at the milk from different animals, Lemery says that cow's milk "is the most used for Food" adding that it is "more pleasing to the Taste, than several other Milks of different Animals."22 Physician William Salmon states that cow's milk "is the first Nourishment of human Kind, being indeed both Meat [food] and Drink.23 Johnston places it first after women's milk, followed by the milk of sheeps, goats, mares and asses. Italian physician Castor Durante disagrees with how highly others rate cow's milk, placing last behind that of women, sheep, goats and asses.24

Several medicinal authors praise milk's ability to nourish.25 Johnston examines several types of animal milks. He advises that cow's milk "is thicker... fatter, and more nourishing", sheep's milk is

"inferior to that of Cowes", goat's milk is "of thinner substance and less nourishment and asses milk is "thinner and more wheyish than the rest, less nourishing"26. Venner explains, "milk is of light digestion, and of much and wholsome

nutriture"27.

Medicinally, milk was considered moist in the second degree. It is generally said to be neither hot nor cold humorally, with Durante and Salmon simply classing it as 'temperate'28. Tobias Venner suggests that it is "more enclined unto cold than unto heat"29., but even this doesn't indicate that it is strongly so. Lemery provides the Paracelsian elements: "Milk contains much Oil, essential Salt, and Phlegm."30

Milk is subdivided into three parts according to the period works: "1. An oily Substance, as Butter. 2. A Caseous or solid Substance, as the Curdy Part. 3. A Serum or wheyish Substance, as its more Watery Parts."31 Each of these three parts are assigned different properties. The oily part, which Durante labels as fat, is like milk, temperate32 and "is balsamick and healing". The solid part "is gross, whereof is made Cheese, and is viscuous and flegmatick"33 which Salmon says is nourishing. Durante finds the watery part to be "cold and moist, nitrious and loosening"34 with Salmon adding that it is opening and cleansing. The idea that the watery part is cold and moist may explain why Venner says that milk tends to be more humorally cold than hot.

Medical opinions on milk are generally favorable. Durante says, "It increases the Brain, fattens the Body, is good for the Hectick Fever, takes away the heat of the Urine, nourishes sufficiently, makes the Body handsom, increases Lust, cures the Cough, opens the Breast, and restores the Tisical [phthisical - consumptive] men"35. Salmon notes that it is "easily concocted

Artist: Jan van der Straet

Man in Bed Drinking From a Glass

['cooked' aka. converted for use by the stomach] and turned into Blood, whereby it nourishes presently and fattens; but it ought to be used chiefly by such as are in [good] Health"36. Venner notes that it is easy to digest, and good "for amending of a dry constitution, and for them that are extenuated by long sicknesse, or are in a consumption, it is by reason of the excellent moistning, cooling and nourishing faculty of it, of singular efficacy."37 Louis Lemery agrees with the other authors on these points, adding, "Milk allays heat in the Urine, pains of the Gout, and sharp Humours in the Breast; and other parts. It is good for those who have taken some sharp and corrosive Medicines. It's likewise good against the Bloody-flux, and in Diarrheas, caused by sharp and pungent Humours."38 Unlike Salmon, he says that it is more like chyle than blood, although he explains that it circulates with the blood where "its grosser parts will be attenuated and broken"39.

Milk was not felt to be optimal for everyone, however. Venner says "it is not good for all bodies; not for them that are subject to windinesse of the stomack and belly, or that have impure, weak, and ill affected stomacks, because it increaseth. wind"40. (This is clearly pointing to people who are lactose intolerant.) He also warned those of a phlegmatic temperament not to drink milk. This is not surprising, given that humor theory advised such people to consume foods with warm, dry humors. Salmon warns that for people of a choleric temperament, milk turns 'adust', referring to the melancholy humor black bile, "and in Fevers it is pernicious, and putriies."41 Durante says that milk is bad for "such as a troubled with Fevers, and Head-achs, and cholick Pains, soreness of the Eyes, and Catarrhs [excessive build up of mucus], the [kidney] Stone, Obstructions; is naught for Teeth and Gums."42 To remedy such problems, he suggests adding salt, sugar or honey to milk.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, p. 255 & 402; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 81; John Covel, "Diary", Early Voyages in the Levant, Thomas Dallam, ed., 1893, p. 120; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 148; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 139; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 20; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; Francis Rogers, "The Diary of Francis Rogers", Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 192; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 300; Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, 1825, p. 285; 2 Teonge, p. 285; 3 Covel, p. 120 & Shelvocke, p. 300; 4 Barlow, pp 255 & 402 & Hamilton, p. 76; 5 Funnell, p. 20; 6 Dietz, p. 139; 7 William Funnell, Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 20-1; 8 Castore Durante, A Family Herbal, or the Treasure of health, 1689, p. 172; 9 Enrico Bertino et al, "The Donkey Milk in Infant Nutrition", Nutrients, Feb 2022, 14(3), p. 403; 10 Tobias Venner, Via Recta ad Vitam Longam, 1638, p. 116-7; 11 Louis Lemery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 181; 12 Hannah Glasse, The Compleat Servant Maid or the Young Maidens tutor, 1677, p. 157; 13 Gervase Markham, The English Huswif, 1631, p. 194; 14 See Aaron Hill, Essays for the Month of January 1717, 1717, p. 38-44; 15 Markham, p. 195; 16, 17Charles Stevens and John Libault, Maison Rustique, Or The Countrie Farme, 1600, p. 90; 18 Lemery, p. 176; 19 John Johnston,The Idea of Practical Physick in Twelve Books, Book 1, Translated by Nicholas Culpeper, 1657, p. 14; 20,21 Lemery, p. 181; 21 Culpeper, p. 14; 22 Lemery, p. 181; 23 William Salmon, Synopsis Medicinæ, 3rd Ed., 1695, p. 42, 24 Castor Durante, A Family-Herbal, Second Edition, 1689, p. 172; 25 See Culpeper, p. 14, Lemery, p. 177 & Venner,p. 114; 26 Culpeper, p. 14, 27 Venner, p. 113-4; 28 Salmon, p.. 42 & Durante, p. 172; 29 Venner,p. 114; 30 Lemery, p. 177; 30 Salmon, p.. 44; 31 Durante, p. 172; 32 Salmon, p.. 44; 33 & 34 Durante, p. 173; 35 Durante, p. 175; 36 Salmon, p.. 45; 37 Venner,p. 113; 38 Lemery, p. 178; 39 Lemery, p. 179; 40 Venner,p. 114; 41 Salmon, p.. 45; 42 Durante, p. 172