Eggs and Dairy in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Animal Products in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 2

Dairy

Dairy products don't usually rate an extraordinary amount of discussion in the period sources. Modern historian Joan Thirsk explains that dairy was felt to be

.jpg)

Photo: Emilio Gómez Fernández

Diary Cows in Riotuerto (Cantabria, Spain)

food for the poor in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, likely because it was so easy to procure. Dairy foods started to become more fashionable in the second half of the sixteenth century when hard cheese and butter garnered interest among the more elite households.1 Thirsk notes the increasing industrialization of dairy farming through the seventeenth century increased interest as men began to become involved in an area that had largely been handled by women. "The old prejudice against cheese was evidently fading, judging by [John] Houghton's clear statement [in 1681] that it was a nourishing food, kept well, and could be carried to most parts of the world without damage."2 The navy's reliance on it as a standard part of the diet at sea testifies to this.

Early seventeenth century author Gervase Markham talks about dairy in general terms in his book The English House-wife, first published in 1615. Even his book title affirms the notion that dairy was primarily the domain of the woman in charge of an English household at that time. Markham opines that the cattle used for dairy products "must be Kine [cows - note that the word cow refers specifically to female cattle] of the best choice & breed that our English House-wife can possibly attaine unto, as of big bone, faire shape, right bred, and deepe [full] of milke, gentle, and kindely."3

Markham goes on to detail each of his points in detail, although not all of them are relevant to this discussion. With regard to the shape of the cow, he advises, "shee must have all the signes of plenty of milke, as a crumpled horne, a thinne necke, a hairy dewlappe, and a very large udder, with foure teates, long, thicke, and sharpe at the ends, for the most part either all white, of what colors soever the Cow be; or at least the fore part thereof, and if it be well haird before and behinde, and smooth in the bottome, it is

Gervase Markham, From The Perfect Horseman (1655)

a good signe also."4 He adds that milk cows can be of a variety of breeds, although they should not be a mixed breed. He recommends that when purchasing cattle, the dairy woman "must looke diligently to the goodnes & fertility of the soile wherein you live, & by all meanes buy no Kine from a place that is more fruitfull then your owne, but rather harder; for the latter will prosper & come on, the other wil decay & fal into disease; as the pissing of blood and such like"5. He notes that the amount of milk production of a cow is generally more after they have calved and the temperament is important mainly because it makes them easier for the maid to milk.

Author Hannah Woolley wrote about the role of women in the English household in the late 17th century. She advises the 'gentlewoman' who maintains a dairy needs to be sure it is "kept clean and neat"6. (Here again we see the importance of women in the dairying field in the seventeenth centuries.) Woolley goes into detail about the management of a dairy by 'Country Gentlewoman' although the majority of her comments follow the advice given by Markham a half century earlier. She notes that when "a Cow gives a gallon at a time constantly, the may pass for a very good Milch-Cow; there are some Cows which give a gallon and half, but very few who give two at a time."7 Markham actually suggests that receiving an excess milk from a cow "is a fault rather then a vertue, and proceedeth more from a laxativenesse or loosenesse of milke, then from any abundance... and therefore they are not truly called deepe [full] of milke."8

In 1717, writer Aaron Hill published an essay on dairy farming found in a letter ostensibly sent to him by a member of "a Society of Gentlemen", although he was likely the author. He suggests <

Photo: Hans Hillewaert

Sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia)

that the letter presents "a new, and much more profitable Management of a Dairy, than is commonly known, or practis'd"9. He begins by advising the manner in which the land that the

dairy will be located on should be prepared, talking at length about the use of 'St. Foyn' grass [sainfoin or Onobrychis viciifolia]. "Nothing is so sweet, nothing so innocent, nothing so nourishing, as the St. Foyn; but above all it is observ'd in encrease Milk in Quantity, and Quality, beyond any Grass yet known in the whole World; And it is for this Reason that I advise you to keep Cows upon it"10. Once the sainfoin crop takes root (he recommended five years), the dairyman was to buy 'about four Hundred Milch Cows' from Wales which were to be fed on sainfoin for twelve months or more to produce milk and then sold at a profit. This could then be used to purchase four hundred new milk cows. In this way, "I always preserve my Cows in their full Milk, and find it no uncommon Thing for one of these Welch Cows to be milk'd twice a Day, and afford a Gallon and a Half at a Meal....you will find, that coming from a poor Pasture to a rich, they will prosper, and encrease both in Milk and Size."11

Hill's essay also gives us a connection between the three foods found in the period sailor's accounts which are a part of the dairy animal products discussed here: milk, butter and cheese. Markham notes that the "profit arising from milke... are three of especiall account, as Butter, Cheese, and Milke, to be eaten either simple or compounded"12. Woolley agrees, adding cream to the list of profitable milk products.13 Writer (and self-proclaimed physician) John Shirley noted that a dairy maid's responsibilites included seeing "that Butter and Cheese are made of proper Milks, and in their proper Season."14 He doesn't, however, specify what that season might be, although it is likely in the spring when the milk was generally felt to be of the best quality.

1 Joan Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England, 2006, p. 38-9; 2 Thirsk, p. 132; 3,4 Gervase Markam, The English House-wife, 1631, p. 190; 5 Markam, p. 191; 6 Hannah Woolley, The Gentlewomans Companion, 1675, p. 111 & 194-5; 7 Woolley, p. 200; 8 Markam, p. 192; 9 Markam, p. 194, 9 Aaron Hill, Essays for the Month of January 1717, 1717, p. 35; 10 Hill, p. 36-7; 11 Hill, p. 38; 12 Markam, p. 195; 13 Woolley, p. 201; 14 John Shirley, The Accomplished Ladies Rich Closet of Rarities, 1696, p. 143;

Dairy and the English Navy

As mentioned several times, butter and cheese were were a standard part of the navy diet during the golden age of piracy. For the most part, the navy's method of sourcing and distributing them was the same, so rather than repeat information in the individual butter and cheese entries, the navy's use of these foods will be discussed in detail here so that the overlapping material isn't presented twice and the individual entries can focus on material found in the sailor's accounts from the period.

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

Preparing Cargo, The Port of Bordeaux, Seen

from the

Wheat Dock (1776)

The use of both butter and cheese by the English sea service is ancient. Cheese is the more ancient of the two based on an order by King Henry III to the Sheriff of 'Hants' [Hampshire] to procure "20 weys [about 175 pounds] of hard cheese" for a voyage to France in 1253.1

Historian David Loades identifies butter as part of the naval diet in the first half of the 14th century.2 By 1565, the two were both included in the naval diet. General Surveyor of Marine Victuals Edward Baeshe was required to provide "half a quarter of a pound of butter" (or an eighth of a pound) and a quarter pound of cheese on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays each week.3 Curiously, cheese appears to have taken a slight detour from the standard supply according to a February 1637 victualling contract which states that cheese was to be issued at each meal on those days except for Friday dinner4, a fact verified in Monson.5 The same amount of butter was apparently issued through the golden age of piracy, although the description was modified to the much simpler 'two ounces' at some point before that.6

The 1677 Victualling Contract, established about a decade before the beginning of the golden age of piracy made some minor changes to the naval specification for butter and cheese. It permitted the substitution of "a wine pint of sweet olive oil" for butter and cheese7 when a ship was traveling south of the 39th North parallel because it was easier (and cheaper) to obtain olive oil in the Mediterranean. It also specified the type of cheese that each sailor was to receive as "four ounces of Suffolk cheese, or two-thirds of that weight of Cheshire"8. This was reaffirmed in a letter from the Admiralty to the Navy Board in January of 1701.9

Writing of the food he saw served to the English Navy a few years after the end of the golden age of piracy in 1729, French author César de Saussure said that each mess of four sailors received "half a pound of butter for breakfast, and the same for supper"10. The butter would have likely been put in the oatmeal at breakfast and the peas at dinner. In defending the master's treatment of the men who mutinied and turned pirate on the merchant ship Adventure, surgeon Samuel Nixon mentioned that they "had Burgoo [oatmeal] for Breakfast, with Butter and Sugar" three days a week.11 Still, it is interesting that de Saussure specifies that butter is served at both meals, resulting in a total of four ounces of butter per four man mess per day where the naval menu only calls for two.

The supply of butter and cheese were different from any of the other foods supplied to the navy. The Navy Victualling Board purchased them under one year contracts with a single victualler with the contract starting September 29th (Michaelmas). The contract was complicated by the fact that supplies

Artist: James Richard Barfoot

Grocer and Cheesemonger, Wellcome (19th century)

of butter and cheese were could not always be depended upon. To alleviate this, "a single contractor undertook to supply, not a given quantity, but whatever amount of butter and cheese the navy required, as demanded, at a contract price for [butter and cheese, so that]... the contractor stood the gains and losses. The Victualling Commissioners expected the contractors to consider the future [prices and supply]." Predicting any commodity market a year in advance was as impossible then as it is today, resulting in the commission being "put to more trouble by its butter and cheese contracts than by any other kind.”12

Even so, there were typically three or four contracters bidding on the butter and cheese contract; Paula Watson notes that there were four bidders for the contract in 1703, with the lowest bid being offered by Richard Maundrell who managed to keep the annual contract until 1709. His responsibility "was to supply all the butter and cheese required at London and the outports for a year on a warranty that if any went bad within six months of delivery he must replace it or stand the loss. The prices were 3-1/2d [pence] per lb for butter and 1-3/4d [pence] p. lb. for cheese. He was responsible for transporting the provisions by land and sea when necessary."13

Historian Daniel Baugh says that the London Cheesemongers responsible for supplying the butter and cheese were very organized, "and the low bidder was usually a specialist, or a partnership of specialists."14 Maundrell had a network of 'agents and correspondants' throughout England which likely contributed to his ability to bid so competitively, being able to source from different markets.15 In the last decade of the 17th century, Joseph Herne and Thomas Rodband supplied all the naval cheese, "and two-thirds of that came from the latter; and it would seem therefore that the well-known monopoly of the London 'cheesemongers' in the eighteenth century was already largely a fact by the last decade of the seventeenth century.”16

1 Calendar of Liberate Rolls, 1251-1260, Vol. 4, 1959 p. 140; 2 Elizbethan Naval Administration, CS Knighton and David Loads, eds, 2013, p. 594 & David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 84; 3 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 140; 4 CSP Domestic, 1636-7, 1867, p. 452-3; 5 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 56; 6 See for example, Monson, p. 56 & J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 166; 7 Tanner,A Descriptive Catalogue..., p. 167; 8 Tanner, p. 165-6; 9 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 255; 10 César De Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 364; 11 Samuel Nixon, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 254; 12 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole, 1965, p. 412; 13 Paula K. Watson, “The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714”, University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 100; 14 Baugh, p. 412; 15 Watson, p. 100; 16 John Ehrman, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction, 1957, p. 149

Naval Butter and Cheese Food Quality

Butter and cheese were produced primarily in the summer, although they were available for purchase year round. The challenge for the cheesemongers was to find ways to keep them fresh enough to be consumed, particularly when delivering them in the winter months. As a result, both were heavily salted and packed in casks before being loaded on a ship. The casks were then stored in the hold of the ship with other provisions like water, meat and beer.1 Where food was salted "the process was often inefficient... The victuals had thus either

Dairy Production, Deutsche FotothekLandwirtschaft & Milchverarbeitung & Käse (17th-century)

to be bought long before they were needed, with the risk (considerable in this period) of deterioration before they were required, or else purchased only a short time before they were consumed, with the consequent administrative difficulties."2 By 1731 Regulations and Instructions related to his Majesty's Service at Sea specified that "In the Victualling His Majesty's Ships for Foreign Voyages, there shall be supplied three Months Butter and Cheese, the Remainder of those Species being to be made up in Olive-Oyl"3. (Note that although the order was issued six years after the end of the golden age of piracy, historian N.A.M. Rodger points out that the Instructions were "largely a codification of orders issued at various dates in the past as far back as 1663"4, so, it may have been in place during part of the period of interest.) This is half the 6 month warranty period, possibly recognizing the difficulty of keeping butter and cheese edible for even that amount of time. The substitution of olive oil for butter had been an option since at least the 1677 victualling contract for ships traveling south of the 39° North latitude. Most naval vessels on a 3 month long journey during this period were likely to cross it.

Ship's Purser in 1787, Players Cigarette Cards,

History of Naval Dress, No 13, 1929

In an effort to keep them fresher and avoid being stored in naval warehouses for long periods, cheese and butter were delivered directly to the ships by the contractor.5 This meant that the navy had little chance to inspect it, relying on the ship's purser inspection of food coming aboard to make sure it was good. As a further defense against the contractor delivering butter and cheese in poor condition, the navy required them to provide a six month 'warranty' starting on the date of delivery so that the contractor had to take them back if they proved rotten or inedible. Richard Maundrell's 1703 contract specifically noted "that if any [butter or cheese] went bad within six months of delivery he must replace it or

stand the loss."6 This requirement continued during the remainder of the golden age of piracy and beyond.7 Likely with the warranty in mind, the 1731 Regulations and Instructions related to his Majesty's Service at Sea ordered, "Condemned Butter is never to be flung over board, but to be returned into His Majesty’s Stores, unless the Boatswain shall want any for the Ship's Use, in which case he may be supplied with what is necessary, and shall be charged therewith."8 (The boatswain sometimes requested rancid butter for use as grease on mechanical parts of the ship.)

Regardless of all the efforts made to insure that good quality butter and cheese were provided to naval vessels, their quality was often a source of complaint by those in the service, typically leveled at the contractor. A variety of them come from the decades before the golden age of piracy. In Nathaniel Boteler's dialog, dating to the 1630s, he points to the "the Rotteness of the Cheese, vileness of the Butter, and badness of the Fish; the which sorts of provisions cannot allow any the like excuses [referring to an inability of meat to absorb salt during certain periods]"9. While serving aboard the

Rotting Cheese

fifth rate HMS Augustine in 1661, Edward Barlow said that the meat had to be dressed "with a little stinking oil or butter, which was all colours of the rainbow, many men in England greasing their cartwheels with better"10.

In his journal, Admiral Thomas Allin of HMS Royal James reported that they received provisions on august 8th of 1667, "but the butter and cheese was so bad that we returned all the cheese, being rotten, and 8 of 9 firkins of butter, it stank so."11 Three and a half years later, Thomas Binning serving aboard a navy pink reported to the Navy commissioners that he had refused a delivery of provisions by a wherry of "with 6 or 7 bags of bread and some cheese, the last was rotten and stinking."12 Samuel Pepys' 1677 Victualling Contract was an attempt to improve naval victualling, but in September of 1683, Sir John Berry reported that he had thrown away "30 butts of stinking beer and ten more defective, with a quantity of stinking cheese" aboard the HMS Henrietta.13

Complaints about the butter and cheese were not confined to the years before the golden age of piracy. In July of 1702, Admiral of the Fleet George Rook journeled that while at Torbay, "Great complaints coming from all the commanders of the fleet of the badness of the butter and cheese, ordered a survey thereof, and the agent victualler to make an equal distribution of what is fit to be eaten."14 In September the next year, the Victualling Board told the Secretary of the Admiralty that the Captain of HMS Tiger wrote "complaining of the badness of his beer, butter, and cheese. ...the butter and cheese... was furnished at the latter end of the cheesemonger's contract, before new could be procured, though he had the best that could then be got. But the same will be the cheesemonger's loss."15 Here we see the six month warranty in action.

Paula Watson points out that during the early years of Queen Anne's War (1702-13) "bad provisions

was one of the causes of the high rate of sickness and death among the seamen" part of which fell on the victuallers and part of which were a result of the amount of time a naval ship took to reach its destination without any method of preserving foods like dairy beyond salting them.16 The English naval administration recognized this. In October of 1705, Rear-Admiral John Jennings reported bad butter was delivered to the fleet from Portsmouth. The Victualling Board informed the Admiralty that they had spoken with the supplier who insisted the butter was good when shipped. The admiralty suggested

Ship's Purser in 1787, Players Cigarette Cards,

History of Naval Dress, No 13, 1929

that the butter had gone bad during a long sea voyage. This they felt was compounded by the fact that butter and cheese was "not to be had in that country [referring to the Portsmouth area] at any rate."17 Similar recognition of this problem is found in a letter to the Admiralty Secretary from the Victualling Board in March of 1718 explaining that a fleet going to the Mediterranean could not be supplied with butter and cheese because those foods "not holding good for a longer time in those hot countries, it will therefore be absolutely necessary that a timely provision be made abroad of wine and oil to answer the remainder of those species"18. They recommended the Victualling Agent at Lisbon be given the responsibility for supplying what would be needed for a four month stint in the Mediterranean.

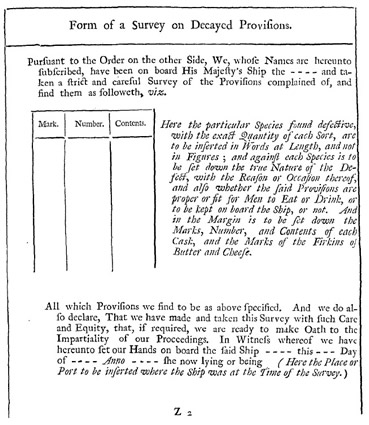

This doesn't mean there weren't still problems with the navy's dairy food after 1703. The 1731 Regulations and instructions included a "Form of a Survey on Decayed Provisions" in its pages (seen at right). While the form is for the most part generic, the last line of the explanation for how to fill out the form states that "in the Margin is to be set down the Marks, Number, and Contents of each Cask, and the Marks of the Firkins of Butter and Cheese."19 This wasn't the only recognition of the dificulty of obtaining good dairy products by the navy during this period. Historian N. A. M. Rodger cites a mid-eighteenth century naval document which explains that the butter "next to the firkin [cask sides was] not fit to be issued"20

1 Brian Laverly, The Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, 1600-1815, 1987, p. 189; 2 John Ehrman, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction, 1957, p. 145; 3 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, 1731, p. 118; 2 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, 2004, p. 320; 5 Paula K. Watson, “The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714”, University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 101; 6 Watson, p. 100; 7 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 83 & Baugh, p. 426; 8 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, p. 63; 9 Nathaniel Boteler, Colloquia maritima or Sea Dialogues, 1688, p. 70; 10 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, p. 69; 11 Thomas Allin, The Journals of Sir Thomas Allin, 1660-1678, Volume II, 1660-1678, R. C. Anderson, ed., 1940, p. 7; 12 Sept. 30, 1672, CSP Domestic 1672 May 18th - Sept 30th, 1899, p. 675; 13 Her Majesty's Stationary Office, The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth, 1887, p. 94; 14 George Rook, The Journal of Sir George Rook, Admiral of the Fleet, 1700-1702, Oscar Browning, ed., 1897, p. 169; 15 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 261; 16 Watson, p. 139; 17 Merriman, p. 276; 18 Daniel A Baugh, Naval Administration in the Age of Walpole, 1965, p. 421; 19 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, p. 177; 20 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986,p. 92

Naval Cheese Sources

Food researcher Peter J. Adkins notes that "most of the cheeses native to England were ideal for transportation and storage. They were salted, hard-pressed and long-lasting, and could be stowed in the hold of a ship for delivery overseas, or for use by the ship's company."1 Beginning in the 1540s, cheese made in Suffolk was primarily what was used to provision the English army and navy. "[T]he pseudo-monopoly of Suffolk in the naval market

Artist: Alexander Adriaenssen

Still life of a table with Cheese (c. 1638-61)

was punctured. In 1597, Cheshire cheese was supplied to garrisons in Ireland, and the following year Dutch cheese was also considered a viable alternative. Suffolk cheese was not only disliked by sailors and soldiers; at 62 shillings a wey [356 avoipois pounds or 161.5 Kg], it was also more expensive than its Dutch rival at 55 shillings."2

The sailors dislike of Suffolk cheese was almost certainly a result of its ingredients. Around the beginning of the seventeenth century, Suffolk farmers realized that they could make more money producing butter from cream than they could from cheese so they began skimming the cream from the milk before making their cheese. “The skimmed-milk, or ‘flet-milk’, cheese had the reputation of being dry and so hard that it was difficult to cut, let alone eat and digest."3 Unlike Suffolk, Cheshire continued to make their cheese with whole milk resulting in a better eating cheese. "Cheshire acquired a reputation for good quality, which was said to be due to the pastures found there and the skill of the dairymaids."4 By the mid-seventeenth century Cheshire became popular throughout England. In the 1660s, "London markets responded enthusiastically to that whole milk cheese."5 It was apparently appreciated by some naval men as well, as clergyman Henry Teonge boasted that the captain of the HMS Assistance "feasted the officers of his small squadron with [a variety of foods and] last of all, a greate Chesshyre cheese: a rare feast at shoare [at Cabo da Roca, Portugal inn 1675]."6 Not everyone was apparently a fan of Cheshire, however. Sir Edward Spragg wrote the Naval Comissioners in 1667, "The ships are victualled with Cheshire cheese, half a pound for a pound, which the men extremely grumble at."7

Denis Gauden, Surveyor of Marine Victuals for the Royal Navy from 1660 through 1677, was instrumental in seeing Cheshire cheese established as a source of cheese for long naval voyages. Even before he was made Surveyor, he was one of several victuallers to the navy in 16508, supplying them

with cheese and other foods that year, "having been appointed to weigh and receive into the stores all the cheese bought of Mr. Harris, Lucas Lucie and partners, for Ireland, and also to take warehouses, and employ persons to dress and look to the same until shipped for Ireland, and also to hire vessels to transport the cheese, and to

Artist: Isaak Cruikshank

Political Cartoon 'Suffolk Rats protecting their Cheese', The sign farright says 'Hard Cheese' (1795)

set carpenters on work to fit the vessels, and it".9 He actively supplied the navy during the next two years, providing them with both Suffolk and Cheshire cheeses and continued to victual the navy during the 1650s and after the Restoration.10 "It was Gauden who pioneered the idea that Cheshire could be a reliable and substantial source of cheese for shipment over long distances."11

It was during Gauden's tenure as Surveyor that the 1677 Victualling Contract was made, specifying that each sailor was to daily receive "four ounces of Suffolk cheese, or two- thirds of that weight of Cheshire."12 This language remained throughout the golden age of piracy, appearing in the 1701 orders of the Admiralty to the Navy Board and the 1731 Regulations and instructions.13 Before that, no specification was made as to the type of cheese which was to be supplied to the navy.

The difference in weights is curious and no one specifies why one third less Cheshire cheese could serve in place of Suffolk cheese. One explanation for this is that it provided some financial incentive to the victuallers to provide the Cheshire cheese that the men preferred. Cheshire cheese was made with whole milk, while Suffolk was made with skim during the latter seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. As a result, Suffolk cheese was drier than Cheshire and, all other things being equal, would last longer and should prove to be more likely to remain good for the required 6 month period of the warranty. Suffolk was also cheaper than Cheshire. So it was to the victualler's advantage to supply Suffolk cheese if it were a one-to-one choice. This is almost certainly why the victuallers were permitted to supply 2/3 the quantity of Cheshire cheese. There is no record how the sailors felt about receiving less of an allegedly better cheese, if they even understood that this occurring.

While Suffolk and Cheshire cheeses were preferred, what was purchased by the victuallers was not limIted to these two types. Peter Atkins provides a list of cheese purchased between June of 1649 and December of 1652 for the navy. This data is taken from the State Papers which provide an incomplete picture, not always including complete information and sometimes combining items other than cheese in shipments. However, from the chart, which includes.64 purchases of cheese and possibly other items, 24 were specified as Cheshire cheeses, 11 were Suffolk and 20 were from other locations. The tonnages for the period shown are remarkably

Photo: Jon Sullivan - Modern Cheshire Cheese

similar - 2474 tons of Cheshire, 2196 tons of Suffolk and 2289 tons of other types.14 This likely has as much to do with what was available to the victualler making the purchase as anything else. Note that these purchase took place about a quarter century before the language specifying Cheshire and Suffolk cheeses was placed in the 1677 contract. Not ha

Even though the language of the contracts we have are specific about the type of cheese to be purchased for the navy is specific, the victuallers selected to purchase cheese apparently continued to purchase varieties of cheese not mentioned in the contract. Writing about the period during the War of the League of Augsberg (1689-1697), historian John Ehrman says that the victuallers procured "butter from Suffolk and the other eastern Counties; and cheese mainly from Cheshire, but also from Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Warwickshire."15 Atkins explains that "by 1729–1730 Suffolk had slipped to only the fourth-largest source of cheese for the London market. The top-three sources were, first, Cheshire; second, the barge traffic along the Thames from Wiltshire; and, third, the Humber ports, drawing their supplies down the Trent from Derbyshire and adjoining counties."16 So if Suffolk cheese was, as the name suggests, made in Suffolk and Cheshire cheese in Cheshire, types of cheese not mentioned in the contract were being supplied. This again probably has much to do with availability as anything else.

About thirty years after the end of the golden age of piracy, Suffolk cheese was removed from the naval victualling list. "There were frequent complaints against it, and in 1758 the decision was taken to switch to Cheshire and Gloucester cheese, even though they were considerably more expensive, and probably did not keep so well."17

1 Peter J Atkins, “Navy victuallers and the rise of Cheshire Cheese”, International Journal of Maritime History, Vol. 34 Issue 1, Feb. 2022, p. 196; 2,3 Atkins, p. 199; 4 Atkins, p. 200; 5 Paolo Savoia, “Cheesemaking in the Scientific Revolution”, Nunclus, Vol. 34, Issue 2, 2019, p. 444; 8 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Hentry Teonge, 1825, p. 27-8; 7 Item 115, CSP Domestic 1667 Jun -1667 Oct, 1866, p. 367; 8 Item 120, CSP Domestic 1650 Feb - 1650 Dec, 1876, p. 262; 9 Item 40:21, CSP Domestic 1650 Feb - 1650 Dec, 1876, p. 121; 10 Atkins, p. 203 & 204; 11 Atkins, p. 206; 12 J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 166; 13 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 255 & Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, 1731, p. 61; 14 Data taken from Appendix I, Atkins,, pp 207-209; 15 John Ehrman, 1957, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction, p. 145-6; 16 Atkins, p. 200; 17 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986, p. 85