Eggs and Dairy in Sailor's Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Animal Products in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 4

Called by Sailors: Butter

Appearance: 23 Times, in 20 Unique Ship Journeys from 15 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Kinsale, Ireland; London, Greenwich, Torbay, The Downs, England; Rotterdam, Netherlands; Ostend, Belgium; Bergen, Norway; Brest, France; St. Helena; Mauritius; Bandah Aceh, Jakarta, Indonesia; Nicobar Islands; St Catherine's Island, Brazil; Juan Fernandez, Chile; Cape Cod, Massachusetts

Butter was apparently an important part of the European diet and in England in particular. Recalling his soujourn through England in 1727, César de Saussure commented, "English people consume a great deal of butter, and they do not know how to prepare fish and vegetables except with this ingredient melted."2 He noted that half a pound of butter was given to every four sailors during his voyage aboard HMS Torrington.3 French Physician Louis Lemery explained, "Every Body knows, that Butter is used every where, and there is hardly any Sauce made without it. The Northern People make more use of it than any; and 'tis pretended, that 'tis Butter that makes them look fo fresh and well."4

Salted butter was a standard part of the English naval sailor's diet and was frequently found

Artist: Floris van Schooten

Still Life with Butter, Grapes and Silver Cup (17th Century)

in the diets of other sorts of English sailors. Yet, this staple is rarely found in the naval accounts from the period. This may be because it was so familiar to English navy sailor, it wasn't discussed in detail by them. (The navy's use of butter and cheese with reference to official records from the period is discussed in detail on the previous page.) Of the two sailor's mentions of butter, one is found in The Journal of Sir George Rook who was Admiral of the Fleet at the time. Rook requested a survey of the butter in the fleet at Torbay following "[g]reat complaints coming from all the commanders of the fleet of the badness of the butter and cheese"5. The second mention is yet another complaint, this by lifetime sailor Edward Barlow aboard the HMS AugustainUnfortunately for those at sea, butter tended to be in storage, sometimes for months, before it was brought aboard. This is likely the cause of Barlow's complaint that the butter "was always served out to us without scraping, the foul and the clean together, and the rotten with the sound, and mouldy and stinking and all together, and we had Hobson's choice, that or none"6. He indicates that although the Naval Board allowed the purser to discard an 1/8 of his supply of butter and cheese (representing undesirable parts which were scraped off and discarded as they decayed), the purser preferred not to do this so that he could stretch the supply out and have his account credited on return to England for the butter and cheese which weren't used.

There are actually quite a few interesting details concerning butter found in the sailor's accounts from the period outside of the naval complaints. Barlow mentions it on three different merchant voyages. He explains that the cattle in Norway "have milk and butter pretty plentiful" during the summer in 1675.7 At a stop on the island of Mauritius in 1689, he explained that the cows there "give very excellent good milk, and they make very good butter for present spending [use], but it will not keep very long, by reason of the heat of the weather."8 He also marvelled at the cost of food in Kinsale, Ireland in 1702 where "good provisions were very cheap ...buying good salt butter for three halfpence per pound, and fresh butter for twopence"9.

Artist: Jean-Francois Millet

Young Woman Churning Butter (c. 1848-51)

Barlow's differentiation between 'salt butter' and 'fresh butter' provides an opportunity to discuss the process of making butter and the resulting output. Gervase Markham recommended that dairy woman make butter from cream. (Before the butter making process was commercialized in the early eighteenth century, the farm women dealt with the dairy, selling excess dairy products in local markets. See the previous section for more on this.) Markham recommended, "take your Cream, and through a strong and clean cloth strain it into the Churn". The butter was then to be churned "in the coolest place in your Dairy, and exceeding early in the morning, or very late in the evening" in the summer and "in the warmest place of your Dairy, and in the most temperate hours as about noon, or a little before or after" in the winter. It was to be churned rapidly, listening for the sound of churning to change from "solid, heavy and entire" to "light, sharp, and more spiritly". It was then to be checked to see that it was yellow, recovered and churned "with easie stroaks round and not to the bottom". He warned not to let it get too hot or cold, "for if it be over-heated, it will look white, crumble, and be bitter in taste; and if it be over-cold it will not come at all, but will make you waste much labour in vain".

For sweet butter, the result was to put into a wooden or ceramic contianer with "your bowl or panshion [pancheon - a shallow dish] filled with very clean water, and therein with your hand... work the butter, turning and tossing it to and fro, till you have... wash'd out all the butter-milk... without any moisture" in it. It is then sliced and further dried and then salted with "so much salt as you think convenient, which must by no means be much for sweet butter"10. This is most likely what Barlow was calling "fresh butter".

Sweet butter would not last as long as would be needed for long sea voyages. In his magnificently detailed accounts of the 167 ton merchant vessel Mary Galley, merchant Thomas Bowry lists 30 firkins of butter for a voyage planned for India in September of 1704.11 Butter meant to last for long periods was placed into a firkin, which was a well made wooden cask which held about 9 gallons (about 56 pounds of butter) in the eighteenth century.12 Such butter was typically made during the summer and early fall and packed into these small casks.

Markham explains how butter in casks had to be prepared, skipping the steps in the previous paragraph about making sweet butter.

A Butter Firkin (19h Century)

Rather than wash the butter in water, he warned, "for water will make the butter rusty, or resse". Instead, he advised, "salt it very well and throughly, beating it in with your hand till it be generally disperst through the whole butter"13. The cask was first 'well salted', then the prepared butter was placed into it.

One the firkin was filled, "take a small stick clean and sweet, and therewith make divers hoels down through the butter even to the bottom of the barrel; and make a strong brine of water and salt which will bear na egg, and after it is well boyl'd, well skimm'd and cool'd, then pour it upon the top of the butter till it swim above the same, and so let it settle."14 The firkin could then be sealed and stored in a cool, dry place allowing better preservation against spoilage.

Historian Joan Thirsk notes that the "Dutch were more expert than the English at keeping butter fresh" in the mid-seventeenth century, importing their best butter to sell to those in the know in England and suggesting that it may have been they who taught the English how to preserve butter well.15 As seen in the previous section, there were still problems keeping the butter fresh.

Still, butter was an important staple to sailors. No where is this made more plain that in a secondhand account of a coal vessel sailing from Newcastle which was written by slave ship master Thomas Phillips in 1693. He explains that the

collier master...having lock'd up the firkin of butter from [the crew], contrary to custom, and plying to windward with the tide among the sands, standing on one tack as near a sand as he thought proper, order'd the helm a-lee [on the sheltered side], to go about; when the ship was well stay'd [pointing into the wind], he call'd to hale [haul] the main-sail, but his men answer'd unanimously, that not one of them would touch a rope till the firkin of butter was brought to the mast. He began to expostulate with them, but to no purpose, and seeing the ship drive near the sand with all sails aback, he promis'd them they should have it assfoon as the sails were trimm'd, and the ship had gather'd way; the men reply'd, that seeing was believing; whereupon, finding there was no other remedy, he run down to his cabin to fetch the butter, and laid it at the mast; then the men went to work, but too late, for e'er the sails could be hal'd about and fill'd, the ship struck upon the sand, and never came off again; so that as the sea proverb is, he lost a Hog for a halfpenny-worth of Tar.16

Some information is provided about the quantity of butter brought or bought on voyages. When the privateer ship Speedwell reached Brazil on their way to the western side of the Americas with about 100 men aboard, captain George Shelvocke puchased 300 pounds of butter (about 5 firkins) from a French vessel, the Wise Solomon.17 If he followed the naval practice of giving each man 1/8 of a pound of butter three times a week, it would have lasted about 8 weeks. It was previously noted that the merchant Mary Galley took 30 firkins of butter aboard to sail for India in 1704. The ship had 26 to 30 men aboard for the three year voyage.18

Artist: Jean-Francois Millet

Ambrose Cowley and his men taking in provisions on Juan Fernandez,

From

An Historical Account of All the Voyages Round the World Performed by English

Navigators, Volume I (1774)

If the men received 6 ounces a week, this would have lasted them about a year and month, easily seeing them to India (and then some) under normal circumstances, provided the butter lasted that long. Such quantities paled in comparison to the amounts provided to the English navy. Historian Paula K. Watson reports that the navy supplied 3342-1/2 pounds of butter aboard Sir Cloudesley Shovell's Mediterranean Squadron of eighteen ships in 1703.19

When we think of butter, we think of that made with cow's milk or cream. Ships on long-distance trips to remote locations didn't usually have this luxury. As mentioned in the discussion of milk, William Funnell gives a second-hand account of what some French pirates did to provide themselves with butter and cheese while hiding from the Spaniards off the coast of Chile in the late 17th or early 18th century. The French decided "to come to this Island of Juan Fernando’s [Frenandez], they being twenty in number, and there to lie nine or ten Months; which accordingly they did, and landed on the West side of the Island; then drew there little Armadilla ashoar, and in a small time brought the Goats to be so tame, as that they would many of them come to themselves to be milked; of which Milk they made good Butter and Cheese, not only just to supply their Wants whilst they were upon the Island, but also to serve them long after"20.

Butter was found in many places where sailors stopped although the method for making it wasn't always what they were used to. Two accounts from overseas settlers from around the period of interest provide some insight into how butter was sometimes made outside of Europe. William Betagh (Beatty),

Artist: Pieter di Mare

Farmer Churning Butter from Milk (1777-9)

who sailed with privateer George Shelvocke in 1719 marveled, “In the kingdom of Chili they make a little butter, such as it is; and their way of doing it is remarkable. The cream is put into a sheepskin stript off whole, and kept on purpose: after tying the ends fast, two women lay it on a table, and shake it and sowse it between them ‘till it [the butter] comes [from it.]"21 Writing 20 years earlier, surgeon John Fryer similarly explains that while he was visiting Gambroon [Bandar Abbas, Iran] in 1677, they saw "Butter made before our Eyes, with no other Churn than a Goatskin, in which they shook the Milk till Butter came"22. As Ephram Chamber's Cyclopedia explains, placing milk or cream in goat's skin, suspending "and pressing it to and fro in one uniform direction... quickly occasionals the necessary separation of the unctuous [oily] and wheyie parts."23 (You can see a video showing this process on YouTube.)

Castor Durante says that the best butter "is the fresh, and sweetest, free from all ill tastes."24 Tobias Venner echoes Durante stating that butter is the most wholesome when it is new and 'well tasted'.25 French physicians Charles Stevens and John Libault explain that "butter of a yellow colour is the best: and that of a white colour is the worst: but that which is gathered in May is better than either of the other."26 Louis Lemery agrees that the best butter is "May-Butter"27 advising elsewhere that "[t]he newer your Butter is, the more pleasant and wholesome you will find it"28.

For butter that wasn't fresh, Lemery warned, "when Butter is a little too old, it has undergone an internal Fermentation, that hath exalted and disengaged these same Principles [saline, referring to the one of the Paracelsian principles] which makes it a little sharp, and at the same time oily and unpleasant."29 He adds that salting combats the loss of saline by preventing air from getting in 'the pores' and ruining it. Polish physician John Johnston states, "When [butter] is old, it attains an Acrimonious Quality", although he doesn't give any details.30

From a medicinal perspective, butter was said to be hot and moist in the first degree.31 Using the Paracelsian elements to describe its properties, Lemery advises, "Butter contains much Oil, and a little volatile Salt."32 Venner advises that butter "is very wholsome, especially in the morning. fasting, for hot and 'dry bodies"33. Galen identified a hot and dry temperament as a person with a choleric temperament according to humor theory.

There are a variety of opinions regarding the value of butter in medicine.

Artist: Gillis van Tilborgh -

Boors Eating, Drinking and Smoking Outside a Cottage (1657)

Lemery says, "Butter is nourishing and pectoral [useful for problems of the chest - see the next quote], it opens the Body [works as a laxative], allays the sharpness of corrosive Poisons,

is of a dissolving and digesting Nature, and good

to ease Pains, and remove Inflamations: They use it in Clysters [enemas] against Bleeding, and the Dissentery"34. Johnston provides greater detail on some of these points: "Butter, helps the breast and Lungs, brings up flegm, and is good for cold and dry Coughs to great Quantity, it loosens [opens] the Belly, and is endued with a strong faculty to digest, discuss, concoct and lightly bring up."35 Durante adds that butter "ripens gross Catarrhs [excessive build ups of mucus]; for it extracts the Superfluities which are congested in the Breast and Lungs, cures the Asthma and Cough, [and] mitigates Paines and Aches"36. English Physician William Salmon gives another explanation for the faculties butter possesses: "It is balsamick and healing, smooths and makes slippery all the Passages, eases Pain, nourishes; and bine leberally eaten, induces a healthful habit of Body."37 He doesn't have anything to say against it which may explain de Saussure's comments about the amount of butter the English consumed.

Although Salmon found no fault with butter, other physicians did. Durante warns that it "loosens and weakens the Stomachs of such as use it too much, prepares the Body for the Itch [scabies], and Smallpox."38 He suggests eating binding and astringent foods after eating butter. Expanding upon this, Lemery says that when too much butter is eaten, it will "so much moisten the Fibres of the Stomach, that they lose their springing Vertue". He adds that too much butter can cause vomiting and it "heats much" making unsuitable for "bilious Constitutions"39.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, p. 255, 402 & 550;Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, pp. 74, 78, 81 & 194; William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 146 & 148; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 63; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 24, 254 & 284; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 20-1; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 466; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 8; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 398; George Rook, The Journal of Sir George Rook, Admiral of the Fleet, 1700-1702, Oscar Browning, ed., 1897, 169; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 29; William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1734, p. 235; 2 César De Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 222; 3 Saussure, p. 359; 4 Louis Lemery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 183; 5 Rook, p. 169; 6 Barlow, p. 51; 7 Barlow, p. 255; 8 Barlow, p. 402;9 Barlow, p. 550; 10 Gervase Markham, The English House-wives, 1668, pp. 145-7; 11 Bowrey, p. 194; 12 Edward Phillips, 'Firkin', The New World of Words, 6th ed., 1706, not paginated, Markham, p. 147 & Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 175; 13 Markham, p. 147; 14 Markham, p. 148;15 Joan Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England, 2006, p. 123; 16 Thomas Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal", A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol VI, Awnsham Churchill ed, 1732, p. 175; 17 Shelvocke, p. 29; 18 Bowrey, pp. 114 & 194; 19 Watson, not paginated; 20 Funnell, p. 20-1; 21 William Betaugh (Beatty), A Voyage Round the World, 1728, p. 269; 22 John Fryer, A New Account of East India and Persia, 1698, p. 234; 23 Ephraim Chambers, "Butter", Cyclopedia, Vol. 1, 1741, not paginated; 24 Castor Durante, A Family-Herbal, Second Edition, 1689, p. 170; 25 Tobias Venner, Via Recta ad Vitam Longam, 1638, p. 117; 26 Charles Stevens and John Libault, Maison Rustique, Or The Countrie Farme, 1600, p. 91; 27 Lemery, p. 182; 28,29 Lemery, p. 183; 30 John Johnston,The Idea of Practical Physick in Twelve Books, Book 1, Translated by Nicholas Culpeper, 1657, p. 14; 31 Venner, p. 117 & William Salmon, Synopsis Medicinæ, 3rd Ed., 1695, p. 45; 32 Lemery, p. 182; 33 Venner, p. 117; 34 Lemery, p. 182; 35 Johnston, p. 14; 36 Durante, p. 170; 37 Salmon, p. 45; 38 Durante, p. 170; 39 Lemery, p. 182

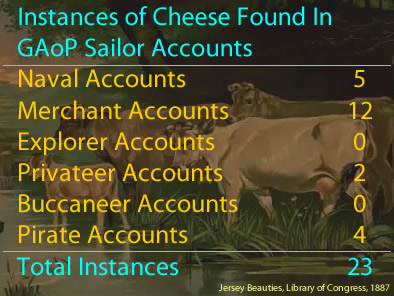

Cheese

Called by Sailors: Cheese

Appearance: 23 Times, in 20 Unique Ship Journeys from 15 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, Portsmouth, Torbay & The Downs, England; Rotterdam, Netherlands; Ostend, Belgium; Iceland; Hierro, Canary Islands; Tangiers, Morocco; Basrah, Iraq; Sri Lanka; Jakarta, Indonesia; St Catherine's Island, Brazil; Juan Fernandez, Chile; Cape Cod & Plymouth, Massachusetts, US

Like butter, cheese was a standard part of the English naval sailor's diet and thus was usually a part of the diets of non-naval sailors. Hard cheese was one of the foods which could keep at sea for long periods, although there were still problems with it going bad, particularly the moister varieties. (An in depth discussion of the navy's use of cheese and the difficulties the navy and sailors had with it can be found on this page.)

There are several mentions of cheese in sailors accounts as food at sea in a naval context, although most of them are complaints. Lifetime sailor Edward Barlow sailed on a couple of different naval vessels during his career,

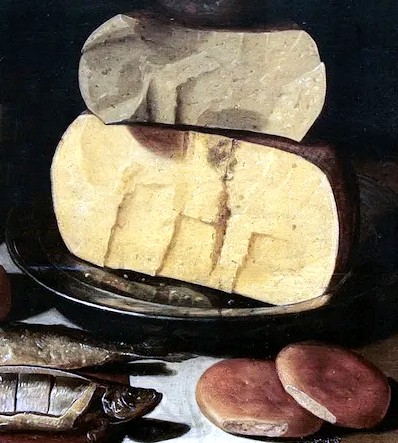

Hard Cheese, Biscuit and Fish on a Table (1615)

although his only comments on cheese come from his tenure on HMS Augustain (Augustine) in 1661. One of them concerned the purser's failure to properly scrape the bad parts) from the cheese before serving it (probably because it was too hard to eat), which is cited in the entry on butter. The other is quite different, concerned with cheese that had been offered to the sailors by people who came to the ship to sell them food while the Augustain was in port at Tangiers. He said they brought "small cheeses, about two pounds in a cheese, and that so salt as though it had lain in pickle one year"2. Another complaint was noted by Admiral of the Fleet Sir George Rook concerning complaints from the fleet's commanders about the 'badness of the butter and cheese'.3

Unlike butter, some of the mentions of cheese by naval sailors aren't complaints. When the HMS St. David returned to the Downs in April of 1671, naval clerk John Baltharpe says in his poem of the journey

When we came in, upon my word.

Our Bread and Cheese, we had made even [eaten all of it],

But we got more, thanks unto Heaven4

However, his thanks is likely due mostly to the ship being resupplied while they waited in port than being a recognition of its quality. Still, unlike the previous comments, he at least seemed to appreciate it.

A final naval instance is rather unique among the food examples. It concerns rwo of Sir Charles Wheler's sons, Trevor and Francis, being put aboard the 4th rate HMS Bristol headed for Virginia at the behest of the king in October of 1676. Samuel Pepys wrote a letter to the commander of the Bristol, explaining that Trevor and Francis were "to receive on board 'the several necessaries following which the said gentlemen design to carry

Artist: William van de Velde the Younger

Fourth Rate HMS Hampshire near Morocco in 1670, This ship was built at the

same time and with the same number of guns as HMS Bristol

for their accommodation in the voyage : viz. each of

them a seaman's chest and mattress to lie on, one runlet of brandy, one hamper of wine, one firkin of butter, one cask of cheese and biscuit, and one hamper of arms for their particular use."5 While iIt is not completely clear from the letter if it was Charles' intent to have them serve on the ship until it reached Virginia, it seems likely. Sons of important people were sometimes placed on naval vessels with the intent of having them learn to be officers and rise through the ranks. Indeed, Francis Wheler became an admiral in the Royal Navy and was knighted for his service. From a cheese perspective, however, it is interesting that the boys had their own food supplied (with the king's blessing, no less) which could be taken as a hint about quality of the food the navy provided.

The majority of the mentions of cheese in sailor's account were little more than that - mentions. 3 of the 12 merchant accounts come from Thomas Bowrey's journey to Holland and Flanders in 1698 in his Duck Yacht. The trip was mostly a pleasure cruise although he conducted some business on the trip. He meticulously kept records of his purchases in a diary. He also mentions that when he was outfitting his Mary galley for a trip to India, he purchased 15 cwt. (hundred weight) of cheese for the outgoing journey.6 Barlow likewise mentions cheese when serving aboard two different ships bound for the East Indies, the Rainbow in 1688 and the Scepter in 1697.7 In the second account, he explains that the Dutch at Batavia (present day Jakarta) brought cheese out to the Scepter. Nearly all of the other merchant vessels in this survey likewise only note that cheese was among their provisions.

Another instance of interest comes from mathematician John Taylor, who was sailing on the merchant vessel St. George to Jamaica in 1686. He explained that some convicts being transported on the ship got loose and got "thro' the bulkhead [wall] of the lazareta [lazarette - store room], and stole from thence 46 bottles of clarret, and one Cheshire cheese and som other things"8. It is one of the few sailor's accounts to specify the type of cheese and it is notably one of the cheeses specified by the navy. (The better of the two. See the discussion on Suffolk and Cheshire cheeses in the previous section on the navy.)

Artist: Thomas Phillips - Location of Lazarette (highlighted in red), Section Through a First-Rate, possibly HMS London (c. 1690)

While sailing to Martinique aboard the merchant Loire flute in 1693, priest and gourmand Jean-Baptiste Labat listed the foods generally provided to him for dinner, noting that "for desert we had cheese, jams, stewed fruits and nuts."9 This could hardly be the food of the typical sailor, although it might be the food of officers, particularly on naval vessels. Another mention of interest comes from Thomas Philips account of his slaving ship Hannibal when they were near the Canaries in November of 1693. "This day we liv’d on bread and cheese and punch, not being able to dress any meat, by reason our hearth and furnaces were shot thro’, which our armourer was about mending."10 The staples bread and cheese didn't require cooking so were the obvious choices while that wasn't possible. A final instance by traveler John Fryer mentions a nonspecific instance of merchant sailors buying local cheese when they were in Surat, India.

Artist: William Russel Birch

Ship in Port, Arch Street, Philadelphia, The Library Company of Philidelphia, 1800

He notes that the locals do not make Cheese, presumably referring to the sort of hard cheeses which would travel well on ships. He adds, however, that they do make "soft Cheese, in which [when it is] pickled, our Seamen keep a good while, as they do their Achars [A mixture of pickled vegetables]."11 (Being non-specific, this isn't counted in the above tally although it most likely refers to being pickled shipboard.)

The use of cheese by buccaneers and privateers are simply mentions similar to what was found in the accounts of many of the merchant sailors. However, the pirate accounts provide information of interest. Two such accounts mentioning cheese involve mutinies on merchant ships. The first concerns Joseph Bradish who led the crew to mutiny on the Adventure in March of 1698. During the trial, surgeon Samuel Nixon explained the diet on the ship before the mutiny, noting that "on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays they had ...Butter or Cheese for Breakfast."12 The second mention of cheese in a muntineering account occured when the Schooner Windbound was seized off Plymouth in May of 1724 from captain John Hay. The vessel's Boatswain supported the captain, so he was forced "into his Boat with some Bread and Water, and Cheese, that he put off from the Vessel"13.

Cheese was sometimes taken by pirates from captured ships. Sailing near Cape Cod, Massachusetts in 1689, pirate Thomas Pound was in need of provision when he came across the sloop Brothers Adventure. "The loot amounted to thirty-seven barrels of pork, three of beef and a good supply of pease, Indian corn, butter and cheese."14 Slaver William Snelgrave's ship was captured by Thomas Cocklyn's pirates in 1719 near Sierra Leone. In his account, he explains,

Photo: Peter Isotalo

Moving a Cask on a Ship, Vasa Cutaway Model (1627.Ship)

"As to Eatables, such as Cheese, Butter, Sugar, and many other things, they were as soon gone. For the Pirates being all in a drunken Fit, which held as long as the Liquor lasted, no care was taken by any one to prevent this Destruction: which they repented of when too late."15

An interesting aspect of cheese on ships is that it was frequently sent, along with other items, as a gift to people the sailors were making deals with for cargo or to government officials so that they would be helpful and/or welcoming to the ship and her crew. (None of these are included in the above tally.) Two different accounts mention sending cheese to African chieftans while trading with them. The first comes from John Atkins' account of his voyages in 1721 when HMS Swallow was at Sesthos (modern Cape Palmas, Liberia) and the chief request a Dashee [gift]. "This brought them from their Knees, as the proper Attitude for presenting it; consisting in a trading Gun, two pieces of salt Ship-beef, a Cheese, a Bottle of Brandy, a Dozen of Pipes, and two Dozen of Congees [shells]."16 The second is found in the accounts of John Ovington in 1689 who was aboard the merchant vessel Benjamin which had stopped at Malemba [Angola], Africa. He notes that the ship's 'Commander' sent an African official "as a Present, a large Cheese with two Bottles of Brandy"17.

The governor of Santiago, Cape Verde received two gifts of cheese from two different ships. The first is another instance from Ovington where he notes that the citizens of the city " are ignorant ...in the Hus-wifery [making] of making either Butter or Cheese, which are therefore valuable, because [they are] rare. And accordingly, a couple of Cheese, twelve Stock-fish, and two Dozen of Poor Jack were kindly received by the Governour of the Town"18. The second comes from Thomas Philips account of the slaver Hannibal from 1693, who, when his officers left the governor after meeting with him, gave him "a promise of sending him a Cheshire cheese next day."19 This is yet is another mention of Cheshire cheese, perhaps suggesting its preferability on a ship.

The cheese required for long distance travel at sea for daily feeding of the sailors was "salted, hard-pressed and long-lasting, and could be stowed in the hold of a ship for delivery overseas, or for use by the ship's company. The realization of this advantage came as early as Henry III's reign, when the commissariat ordered 20 weys [about 356 avoirdupois pounds] of hard cheese for his maritime expedition to Gascony in 1253."20 Soft cheeses weren't durable enough to last so they wouldn't have been regular sailor's food. (There is one exception found in the sailor's accounts, but it was for men who purchased it while on land and then pickled it for later use. Even this would have had a short shelf life.

The process of making hard cheese is described in a variety of books from the period, but a nice summary of making Cheshire Cheese during the period of interest is presented in the article "Cheesemaking in Cheshire, 1550 - 1750" by Peter Adkins and Andrew Lamberton. Their sources are William Jackson's "On the Making of cheese, etc." from a report to the Royal Society in the 1660s21 and an account from John Houghton's Husbandry and Trade paper of July 12, 1695 containing "[a]n account of Cheshire-cheese, as made at Nantwich, I had from a curious housewife"22. Adkins and Lamberton present it in a straightforward numbered list.

.jpg)

Cooking and Straining Cheese, From Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire

raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Vol. 6 (1765)

-

The whole milk as it came from the cow was brought by pail and ‘siled’ [strained] into a cheese tub to remove dirt, and rennet [curdled milk from the stomach of an unweaned calf - see step 2] was added. The sile or sieve was supported on the tub by a cheese ladder. A lid was then fitted to the tub to control the temperature of synæresis (the process of coagulation and expulsion of whey). Jackson gave the height of a cheese tub at about one and a half feet, with a diameter of two feet. It was made from ash staves with ash hoops around the circumference.

-

The rennet (‘stoop’ in the Cheshire dialect) had previously been prepared by taking the stomach of a newly killed calf, cleaning and salting it for four days, and then hanging it by the kitchen fire for six months. This ‘bagskin’ was then soaked in an earthenware pot for four days and the liquid used for a fortnight’s cheesemaking, in a ratio of one part rennet to two or three thousand parts milk. The enzyme rennin in the stoop made the curd coagulate in 30–45 minutes depending upon the acidity of the milk and the ambient temperature of the dairy.

-

When the cheese milk had ‘come’, forming a gel, the dairy woman stirred it with clean hands and a fleeting dish, then scooping out the curds to separate them from the whey. The curds were gathered with her hands and gently pressed, then ‘broke into the vat very small and heaped up to the highest pitch’. The junior dairymaids were now called to ‘thrutch’ the curds by pressing them down ‘with their whole weight’ for up to two hours for a large cheese . This was again to expel as much whey as possible.

-

The curds were then transferred to a cheese vat (chesfat) seven or eight inches deep lined with cheesecloth made of muslin, calico or flax. The curd normally protruded above the lip of the vat ‘straightly [tightly] bound about with a long narrow peice of cloath, as it were a swath; which keeps it to its fashion; and secures it from cracking’. This swath was called a ‘binder’ and in the next century it was replaced by a wooden or metal ‘fillet’ or ‘hoop’. If there was not enough curd to fill the vat, a wooden ‘follower’ was inserted.

-

The vat was placed on a board and pressed for two hours, after which the cheese was put gently into a clean cloth and pressed again for four hours under up to three to four hundredweight, and the process was then repeated with a clean cloth and pressure. After removal from the press, the cheese was put into yet another cloth and left to lie in the vat overnight.It was covered with a lid or ‘bread’.

-

The next day the cheese was salted on the outside in a ‘powdering’ trough, morning and evening for four days, though the largest cheeses had salt mixed with the curd at an earlier stage, about one part salt to 100 parts cheese.

- The salt was then washed off with tepid water, and the cheeses wiped with a hair cloth and placed singly on smooth boards or on ‘sniddle’ in a cool place and turned every day for five weeks. After that, cheeses that were to be matured were stored in a wooden rack (a ‘cratch’) and were at their edible best after twelve months. Some cheesemakers rubbed the outside of their cheeses with butter, using about half a pound for a 60 lb cheese.23

.jpg)

Device for Pressing Cheese, From Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire

raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Vol. 6 (1765)

The cheese mentioned in most sailor's accounts was most likely made from cow's milk. Peter J. Atklins notes that some of the cheese supplied to the English navy was from Essex, where there were originally "large flocks of sheep in and close to the coastal marshes. Essex cheese, however, was less popular than the cow's-milk product from Suffolk. The latter was preferred for naval supply right through to the middle of the eighteenth century, and it was also shipped in large quantities coastwise to London."24 Cheshire cheese, which came to be favored over Suffolk by the navy (as explained previously) was likewise made from cow's

Photo: Wiki User Wilfador - Semi-hard Goat Cheese at a Market

milk, with Atkins estimating there to be 20,000 cows devoted to cheesemaking in Cheshire during the mid 17th century.25 Authors Richard Blundel and Angela Tregear point out that Cheshire cheese was not limited to the production of cheese from the Cheshire Plain but from neighboring counties as well. "Despite their relatively wide geographic spread, these products were generally traded under the generic title, 'Cheshire' cheese."26

Two sailors accounts do mention cheese made from the milk of other animals. One of these has already been discussed in detail in the section on butter - that of the French pirates making cheese from goat's milk while they were on Juan Fernandez Island. They apparently made quite a bit of it, as the author relating the account notes that they made ", not only just to supply their Wants whilst they were upon the Island, but also to serve them long after"27. Surgeon Johann Dietz of the whaler Hope of Rotterdam stopped in Iceland around 1690 where they traded brandy and tobacco with the locals for food which included cheese made from reindeer milk.28 Other sailors who stopped in foreign ports almost certainly traded for or purchased cheese made from the milk of other mammels such as sheep, goats, oxen and similar animals as their store ran out.

John Jonston explains, "The best cheese,

Artist: Januarius Zick - The Cheese Seller, England (2nd Half of 18th c.)

is void of Eyes and holes, not over salted, nor foul with hairs, nor wheyish, nor old, nor hard, nor Ranke."29 Physician Castor Durante advises choosing cheese which is "fresh, made of temperate Milk, but... of a good Pasture."30 The last likely indicates the quality of the plants in the field where the cow giving the milk ate. French physician Louis Lemery has a different view, explaining that "the best in its kind of any sort, is that which is neither too old, nor too new; that which is fat, and salted enough, of a midlling Consistence, of a good Taste and Smell; and lastly, that which has been made of good Milk."31 Physician William Salmon adds that good cheese "smells well, and is fat and full of Butter, is wholesom, moderately hot (probably referring to the humoral properties), of good Juice, and nourishes much. But that which stinks or smells ill, and is lean and without Butter, is less wholesom, of evil Juice, hot, dry and Obstructive."32 Tobias Venner doesn't have much use for cheese, although he indicates that new cheese is marginally better than old cheese.33

Johnston says that the goodness

Photo: Tila Monto - Sheep's Milk Cheese, Spain

of cheese depends on the type of animal milk which was used to make it. That made from sheep's milk "is concocted [basically digested] more easily than other sorts, and affords better nourishment." He rates cheese of cow's milk the next best and goat's milk cheese "worse than either of the former, as being doubtless more hot and thin."34 Lemery says the cow's milk cheese is the most often eaten, having "a very pleasant, Taste, nourishing enough, but a little hard of Digestion". He states the sheep's milk cheese is "easier of Digestion, and is not so gross and compact a Substance as the [cow's milk cheese]; however, 'tis not so nourishing". Goat's milk cheese "'tis not much valued; however, 'tis easily digested and dissolved."35 None of the other authors under study venture an opinion about this aspect of cheese, although several did address it when discussing different types of animal milk.

Medicinally, William Salmon says the humoral properties of cheese are cold and moist, without specifying to what degree this is the case36. As mentioned above, he explains that old cheese is 'hot and dry'. Castor Durante says that fresh cheese "is cold and moist in the second degree, but the old [cheese] is hot and dry."37 Durante's comments echo those of Galen who said that cheese shared it's humoral qualities with milk, which was said to be cold and moist in the second degree when new.38 Striking the Parcesian note, Lemery says that principles of cheese are "much Oil, an indifferent quantity of essential Salt, and little Phlegm and Earth."39

The age of cheese was clearly an important factor to its healthiness. Lemery says, "When Cheese is new, is soft, viscous, and full of moisture, and it's then heavy upon the Stomach, windy, and hard of Digestion;

Artist: Clara Peeters - Hard Cheese and Brown Bread (c. 1615)

however, 'tis nourishing enough, and a little Laxative: ...Cheese that is too old, grows dry, pungent, and burns the Tongue, smells strong and unpleasantly, and produces several other ill Effects"40. This he blames on dryness which is tied to 'attenuation' of the Paracelsian principles. Salmon blames the unhealthiness of old cheese on its "Acrimony, and by how much the older it is, but some much the sharper it is, and the hotter and dryer"41. Venner accuses old, hard cheese of being "altogether unwholesome, for it is of very hard digestion, troublesome to the stomacke, breedeth [the humor] choler adust [black bile], maketh the belly costive [constipated], & is infinitely hurtfull unto hot and dry bodies [humoral temperaments]."42 Galen is opposed to 'old and sharp" cheese because it is "more thirst-provoking, more difficult to concoct and produces more unhealthy humour." He goes on to opine, "among the cheeses one should especially avoid this sort, since it holds absolutely no advantage, whether for concoction or distribution, or the passage of urine, or moving the bowels, just as it also holds none for a healthy humoral state."43

It is interesting that the type of cheese most derided by the physicians was the type issued by the English Navy and likely to have been in use by merchant vessels and thus available to pirates. This was

Artist: George Smith - Cat Caught Mouse Who Was Eating Cheese (mid-18th c.)

a matter of necessity since softer cheese would not last on long voyages. Even if new cheese could be loaded soon after it was made on a ship traveling to the East Indies or the New World, that cheese would be old by the time the journey ended.

Some of the authors make general comments about the healthiness of cheese as a food. Durante said, "It induces Thirst, inflames the Blood, causes the [kidney] Stone, obstructs the Liver, digests slowly, especially if the Stomach be weak, and offents the Reins [kidneys]." When eating cheese, he recommends remedying the diety by "Eating it with Nuts, Almonds, Pears, Apples, &c. it is less hurtful [that way]; it requires a strong Stomach to digest it, and therefore is only good for young men that labour."44 Venner, obviously no fan of cheese, echos the comments made by Durante. He suggests that it is "best for them that leade a studious or generous course of life, to be eaten after other meate [food], and that in little quantity". He suggests it has two bad qualities: "First, it taketh away saiety [fullness], and strengthneth the stomacke, by shutting up the orifice thereof. Secondly, it preventheth the floting of meate, which greatly hinderethe and distubeth the concoction, by depressing it into the bottome of the stomacke"45. He suggests that the best use for it is catching mice and rats.

1 John Baltharpe, The straights voyage or St Davids Poem, 1671, p. 93; Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, pp. 51, 66, 140, 390 & 465; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, pp. 78; 79 & 194; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 139; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 63; Ed Fox, ed., “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 254; Ed Fox, ed., The American Weekly Mercury, Thursday May 21st. To Thursday May 28th. 1724, Pirates in Their Own Words II, 2022, p. 330; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 21; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; Jean-Baptiste Labat, The Memoirs of Pere Labat, 1693-1705, John Eadon ed, 1970, p. 8; Samuel Pepys, Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol. II, J. R. Tanner, ed, 1903, p. 305; Thomas Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal", A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill ed, 1732, p. 181; Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 398; George Rook, The Journal of Sir George Rook, Admiral of the Fleet, 1700-1702, Oscar Browning, ed., 1897, p. 169; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 29; William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1734, p. 235; John Taylor, Jamaica in 1687, David Buisseret ed, 2010, p. 18; 2 Barlow, p. 66; 3 Rook, p. 169; 4 Baltharpe, p. 93; 5 Pepys, p. 304-5; 6 Bowrey, p. 194; 7 Barlow, p. 390 & 465; 8 Taylor, p. 18; 9 Labat, p. 8; 10 Phillips, p. 181; 11 John Fryer, A New Account of East India and Persia, 1698, p. 119; 12 Fox, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 254; 13Fox, Pirates in Their Own Words II, 2020, p. 330; 14 Dow and Edmonds, p. 63;15 Snelgrave, p. 235; 16 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 65; 17 John Ovington, A Voyage to Suratt in the Year 1689, 1696, p.731; 18 Ovington, p. 41; 19 Phillips, p. 187; 29 Peter J Atkins, “Navy victuallers and the rise of Cheshire Cheese”, International Journal of Maritime History, Vol. 34 Issue 1, Feb. 2022, p. 196; 21 Jackson, cited in Full in Paolo Savola, "Cheesemaking in the Scientific Revolution", Nuncius 34 (2019), pp. 449-453; 22 John Houghton, FRS, A collection for the improvement of husbandry and trade, 1727, pp. 403-5; 23 Peter J. Atkins & Andrew Lamberton, Cheesemaking in Cheshire, 1550–1750, Northern History, 612, pp. 189-92; 24 Peter J Atkins, “Navy victuallers and the rise of Cheshire Cheese”, International Journal of Maritime History, Vol. 34 Issue 1, Feb. 2, p. 198; 25 Atkins, p. 201; 26 Richard Blundel and Angela Tregear, "From Artisans to "Factories": The Interpenetration of Craft and Industry in English Cheese-Making, 1650-1950", Enterprise and Society, 7, 4: (2006), p. 4; 27 Funnell, p. 21; 28 Dietz, p. 139; 29 John Johnston,The Idea of Practical Physick in Twelve Books, Book 1, Translated by Nicholas Culpeper, 1657, p. 14; 30 Castor Durante, A Family-Herbal, Second Edition, 1689, p. 171; 31 Louis Lemery, A treatise of foods in general, 1704, p. 184; 32 William Salmon, Synopsis Medicinæ, 3rd Ed., 1695, p. 46; 33 Tobias Venner, Via Recta ad Vitam Longam, 1638, p. 87; 34 Johnston, ibid; 35 Lemery, p, 185; 36 Salmon, ibid; 37 Durante, ibid; 38 Galen on the Properties of Foodstuffs, Owen Powell, ed, 2007, p. 129; 39,40 Lemery, p. 184; 36 Salmon, ibid; 42 Venner, ibid.; 43 Galen on the Properties of Foodstuffs, p. 130; 44 Durante, p. 171-2; 45 Venner, p. 88