Juan Fernandez Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Juan Fernandez Islands Page 1

Juan Fernandez is the the most unusual of the four Western Hemisphere islands discussed here. Unlike Barbados, Jamaica and the Bahamas, it is on the eastern side of South America, far south of the equator and it is the only Spanish-owned island in this group. As a result, there are fewer English books about its history and no rich contemporary accounts of the flora and fauna found there. However, it was an important victualling location for English buccaneers just before the golden age of piracy and for various South American privateers during it.

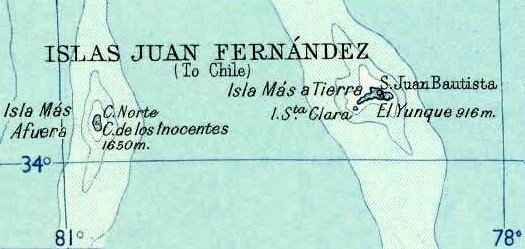

Juan Fernandez is sometimes referred to in period accounts as an island when it is actually three. Two of them are quite close to one another - Isla Más a Tierra ('Island Closest to Land') and Santa Clara - being about 416 miles west of mainland Chile in the South Pacific. The other

Cartographer: Gabriel Bray - Juan Fernandez Islands

island - Isla Más Afuera ('Island more distant') - is an additional 112 miles west of them. Isla Más Afuera is the largest of the three at 19 square miles, Isla Más a Tierra is about 18 and Santa Clara is less than a square mile in size. The islands are so small and far away from the mainland that it is difficult to get any sense of them when they are included on a normal sized map with the east coast of Chile. Even when excluding the Chilean coast, it is challenging to really comprehend their shapes from a map showing the three of them. (See above.) Nearly all the period accounts which state the sailors stopped at Juan Fernandez are referring to Isla Más a Tierra and Santa Clara and most of them specifically mean the former, the more hospitable island of the two.

The history of 'Juan Fernandez Island' aka Isla Más a Tierra (renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966) is a fairly slender volume until well after the golden age of piracy. The island was settled in fits and starts and its only populated village - San Juan Batista on Cumberland Bay - was first established around 1750 by the Spanish government for purposes of defense. However, it did not really develop into continuously-populated settlement until 1877.

Photo: By The Author - Isla Más a Tierra (Robinson Crusoe Island) in January, 2017 |

Juan Fernandez History Related to Food

For the purposes of this article, the history of the island can be broadly divided into two parts: discovery by the Spanish with various attempts to establish a settlement on Isla Más a Tierra and limited cultivation and use by Dutch and English privateers and buccaneers who were left there for various reasons during the 125 years including the golden age of piracy which followed the Spanish discovery. All of these residents were temporary, some being there for a few weeks or months and others for several years. Only the Spanish came truly prepared to settle the islands, so the majority of the lasting cultivation efforts were theirs.

Spanish Discovery and Attempted Settlements

The Juan Fernandez Islands were discovered by none other than Juan Fernandez. He found them by accident

The Dutch Fleet at Callao in 1624 (c. 1644-5)

while trying to determine if it would be faster to sail further away from the South American coast where a ship might avoid what we now call the northern Humbolt or Peru current and the challenging weather conditions it created. This current caused ships sailing south from Peru to Chile to take between three months and over a year when hugging the coast on their voyage.1 Fernandez sailed from Callao, Peru on October 27, 1574 in the merchant ship Remedios with another merchant vessel, sailing "southwestward purposely, testing his theory that the winds and current would be more propitious to a southward voyage if he first sailed to the west"2, arriving in either Valparaiso or Concepcion, Chile thirty days later. Once this faster route was discovered by Fernandez, it eventually the preferred method for Spanish ships to sail south along the western coast of South America. However, it was his citing and naming of what is today Robinson Crusoe Island on November 22nd that is of primary interest here. He didn't name the island Juan Fernandez nor did he call it Isla Más a Tierra; he named the island after Saint Cecilia, whose feast day it was when he first saw the island.

Fernandez apparently promoted the idea of colonizing the islands, although it is not clear that he ever actually visited them. Seventeenth century historian and priest of the Jesuits (Society of Jesus) Diego de Rosales says that Fernandez was the first inhabitant of Más a Tierra. He explains: "Juan Fernandez and other Spaniards of his opinion began to populate this island by putting sixty Indians onto it, who made houses of wood and straw for the farming of the land, brought and raised cattle, took a large sum of fish, and made considerable grains to enter into trade with Peru and the closest cities of

Juan Jufre, Soldier of Fortune cum Entrepreneur

Chile."3 Among the fish Fernandez reportedly shipped off island were conger eels, tuna (atunes) and others as well as very good lobsters. Rosales also says that Fernandez stocked the island with goats and produced oil for use on the main-land from the sea-lions found there. However, as Latin-American historian Ralph Lee Woodward explains, "It has been popular for writers to credit Fernandez with the establishment of the first settlement on the island, but there is little evidence to support such a claim. It is even possible that 'the discoverer' of these islands never even set foot on them."4

Woodward instead says the first known settlement was organized by Spanish soldier-of-fortune turned entrepreneur Juan Jufre, who was apparently approached by Fernandez.5 Jufre organized a reconnaissance mission to the islands in 1575, exploring them and naming the main harbor on Isla Más a Tierra Todos Santos. (It is today called Cumberland Bay.) Jufre used his interest in the island to undertake another expedition which he claimed was intended to settle the island, but which was actually designed to further explore the sea to the west of them. When Jufre's first choice to head this exploratory expedition was unavailable, he chose Fernandez to head it, during which he may have cited New Zealand.6 (He clearly passed by his namesake islands on the way there.) When Fernandez returned to Chile, Jufre was in ill health and was was on the local viceroy's bad side, so Fernandez decided to keep his information secret.

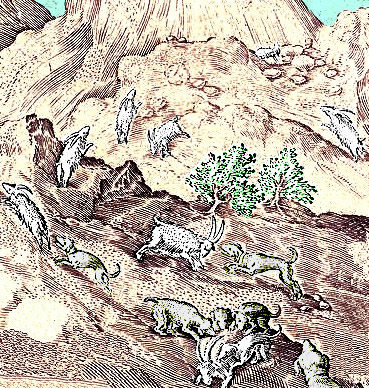

The first Spanish attempt to colonize Isla Más a Tierra occurred in August of 1591, possibly at the behest of Fernandez. However, "historical records of the time seem to suggest that Fernandez himself took no direct part in colonizing the island. Rather, Captain Sebastian Garcia Carreto, a native of Estremadura, was the original colonizer, and he obtained his rights not from the discoverer, but from the Governor of Chile, Alonso de Sotomayor"7. Along with settlers, Carreto brought 'a number of goats' to the island, whose dependents were still clambering about the mountainous island long after the end of the golden age of piracy. Carreto's colony, on the other hand, was abandoned by 1596.

Mapuche Natives Farming at La Mocha, From West Indianischer

Historien Under Theil, By Theodor de Bry (1617)

Spaniards Martin de Zamora, Diego de Ulloa and Fernando Alvarez de Bahamonde attempted to establish another new colony in 1599 with an eye towards using the island's resources to make money. They "established some Indian colonists who had built homes and were cultivating vegetables, in addition to carrying on fishing, sealing, and wood cutting on the island."8 (This sounds so much like the colony which Rosales says Fernandez established that it is likely he confused Fernandez with these three Spaniards.) Based on this description, this settlement was probably the source of the European vegetables found on the island by later voyages. No record of the demise of this settlement is known, although the first non-Spanish European voyagers to land on Más a Tierra in 1616 found no one living there.

There was at least one more Spanish settlement on Isla Más a Tierra at some time between 1662 and 1665 when Jesuit priest Rosales established a colony on the island during his term as Provincial Superior.9 Although Rosales wrote extensively about the history of Chile, including several pages about these islands, his only comment on the creation of his settlement is brief. "[B]eing a Provincial of the Province of Chile, I tried to populate it so that religion could take advantage of the potential of the island"10. This sentence hints at development, possibly planting and cultivating the fauna of the island, but there isn't enough there to draw any definite conclusions. Not that some later authors didn't try. Nineteenth century Chilean historian and author Benjamin Vicuña MacKenna, referring to this line, rather poetically suggests that "it seems that Rosales was the one who scattered by his hand on that fertile soil the first seeds of trees and European vegetables"11.

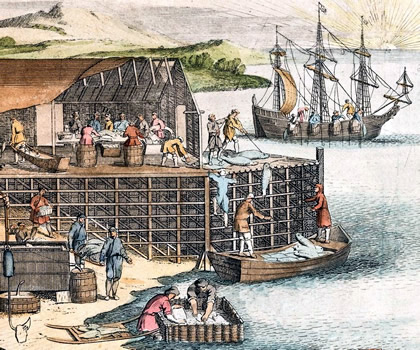

Cartographer: Herman Moll - Cod Fishery, From Map of NA (1719)

One other attempt to create a settlement on Isla Más a Tierra occurred in 1712 when the French and Spanish were allies. Some French entrepreneurs established a fishery which was sanctioned and made use of by the Spanish in Chile. In his account of the voyage of the St. Joseph to gather intelligence on the fortifications of Chile and Peru, French engineer and spy Amédée-François Frézier mentioned this settlement: "some French Men had a Fishery there, under the Direction of one Apremont, formerly one of the King's Guards."12 This was only mentioned by Frézier because a vessel called the St. Charles had struck a shoal near the island as she "was coming to lade Bacallao, or Salt Cod "13. She had been purchased the Spanish from the French to specifically to transport fish from the settlement. All of the sailors on the St. Charles survived and some of them rowed one of her boats back to Valparaiso on the Chilean mainland to get help. They asked the Governor of Valparaiso "to send a Ship to fetch off the Fishermen left on the Island, and lade what dry Fish they had."14 So the French had apparently been catching and salting fish at the Juan Fernandez islands for the Spanish at Valparaiso and other locations on the Chilean coast.

1 Ralph Lee Woodward, Robinson Crusoe's Island, 1969, p. 4; 2 Woodward, p. 8; 3 Diego de Rosales, Historia general de el reyno de Chile, 1877, Translated by the author, p. 284; 4 Woodward, p. 11; 5,6 Woodward, p. 10; 7 Woodward, p. 12; 8 Woodward, p. 13; 9 Woodward, p. 21; 10 Rosales, p. 285; 11 Benjamin Vicuña MacKenna, 'Vida de Diego de Rosales', Historia general de el reyno de Chile, Translated by the author, 1877, p. xxxii; 12,13 Amedee-Francois Frézier, Voyage to the South Seas, 1717, p. 95; 14 Frézier, p. 96;

Destruction of Provisions by the Spanish

Regardless how Más a Tierra was cultivated and stocked with animals, the resulting abundance of food combined with a general neglect of the location by the Spanish made it a wonderful first stop for the Europeans sailing around Cape Horn. Such men were often sick with scurvy and the Juan Fernandez Islands provided them with a excellent place to solve that problem so they could get on with the business of capturing Spanish ships and settlements on the west coast of South America. It also made the islands a splendid last stop before these men sailed back around the Horn on the way home. Eventually the Spanish thought better of leaving a location so helpful to their enemies with an abundance of provisions.

Artist: Jan van der Straet - Mountain Goat Hunt (1578)

In an effort to decimate the flourishing goat population, Spanish naval commander Antonio de Vea placed ferocious dogs on the island around 1676. However, goats are nimble creatures and they simply fled to the mountains where the dogs could not catch them. Nevertheless, "it did for a time accomplish its intended purpose for the goats were also out of the reach of interlopers at such heights. The dogs, denied goat flesh, turned on the seals and sea lions of the shores, but eventually, the dogs either died off or, more likely, the buccaneers killed them."1

The Spaniards continued set dogs on the Isla Más a Tierra to eliminate the goats; shortly after the end of the golden age of piracy, Sailor Richard Walter reported that "the great numbers of goats, which former writers described to have been found upon this Island, are at present very much diminished."2 He said that by 1741, the dogs were "masters of all the accessible parts of the Island… and [have] multiplied to a prodigious degree."3 Writing of a visit to the island in December of 1743, Spanish Dons George Juan and Antonio de Ulloa said, "Here are many dogs of different species, particularly of the greyhound kind; and also a great number of goats, which it is very difficult to come at, artfully keeping themselves among those crags and precipices, where no other animal but themselves can live."4 This is the first account to mention the type of dogs used to try and eliminate the goats. They go on to state that the dogs were put there 'not many years ago' by the President of Chile and the Viceroy of Peru, which suggest that these were a different pack of dogs than those placed on the island by de Vea.

Goats may not have been the only provisions destroyed by the Spanish. The first published Dutch account of the island from 1616 states that they found hogs and possibly other provision animals on the island5 which were often placed on islands by the Spanish and Portuguese to establish a food supply for future ships. The Dutchmen were unable to catch any of these other animals, although it seems unlikely that they would have misidentified pigs or hogs. No later account mentions provision animals other than goats, so the Spanish may have removed or slaughtered pigs and any other animals which had been on the island in 1616, although this is not documented anywhere. The Spanish may also have removed some of the crops which were close to the shore as well, based on some of the reports of such provisions being found only in early non-Spanish accounts.

1 Ralph Lee Woodward, Robinson Crusoe's Island, 1969, p. 22; 2,3 Richard Walter, A Voyage Round the World, 1748, p. 125; 4 George Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, A Voyage to South America, 1758, p. 223; 5 Jacob Le Maire, The relation of a wonderfull voiage made by William Cornelison Schouten of Horne, 1619, p. 28