Juan Fernandez Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Juan Fernandez Islands Page 2

Juan Fernandez History Related to Food

Cultivation by Stranded Buccaneers and Privateers

Other than Rosales' apparently brief attempt to establish a community in the

Robinson Crusoe, Surprised to Find Himself in This Article, From

My Robinson Crusoe Storybook, By Lucy L Weeden (c. 1890)

mid 17th century, the Juan Fernandez islands remained unoccupied by the Spanish during the seventeenth and first half of the eighteenth centuries. And while it was never home to any enduring community during this period, it did host a few occupants from time to time. They provide what are perhaps the most unusual example of people cultivating the plants and animals of any of the islands found in this article.

Various buccaneers and privateers were stranded on Isla Más a Tierra in the seventeenth and first quarter of the eighteenth century. During their stay, they found it necessary to their survival to harvest what they could from the fruitful island. Most people familiar with the history of the Juan Fernandez Islands associate them with the stranded mariner Robinson Crusoe, for whom Más a Tierra was renamed, or his counterpart, stranded mariner Alexander Selkirk, for whom Más Afuera was renamed. While Crusoe is the stuff of fiction, his inspiration Selkirk really did spend four years and four months on Más a Tierra beginning in 1704. (Curiously, Selkirk was apparently never on the island which now bears his name.) Yet he was not the first sailor to fend for himself after being left on the island; in fact, he wasn't even the second, third or fourth.

The honor of the first European trespassers to make Isla Más a Tierra their temporary home goes to three gunners from the one of the Dutch Nassau Fleet's eleven marauding vessels - the Delft, captained by Cornelius de Witt. The Fleet had stopped at the island in April of 1624. Three soldiers and three gunners from the Delft "had been so ill that they had pleaded to be left on the island rather than continue aboard ship. The captain of their ship, Cornelius de Witte, granted their request, but their fate is unknown."1 Since no account exists of their time on the island with even the period of their occupation being unknown, it is impossible to say what their impact

Artist: Howard Pyle - Marooned (1887) was on the plants and animals there. It is known that Spaniards from mainland Chile occasionally visited the island to fish2, they were most likely captured by them and brought back to Chile at some point.

Another sailor may have been shipwrecked on either Más a Tierra, although who he was and when he was there are not known from the details given. Basil Ringrose, who was aboard Captain Bartholomew Sharp's Trinity when it stopped at the island in December of 1680 related the story: "our Pilot told us, that many years ago a certain ship was cast away upon this Island, and onely one man saved, who lived alone upon the Island five years before any ship came this way to carry him off."3 Provided this tale was true, this sailor would have held the record for the most time stranded on Juan Fernandez islands among those considered here. It is unfortunate that no other information of this man's tenure on the island exists.

The next resident brought to the Juan Fernandez islands is probably the second most renowned European castaway. This was a native whom the buccaneers called Will who was taken aboard

Will the Native on Isla Más a Tierra

the Trinity near Roatan, an island off Honduras. The buccaneers liked to have Moskito natives with them because they were so good at hunting and fishing. In fact, Will was roaming the island trying to catch goats in January of 1681 when the ship sailed without him. Ringrose explains that the reason for their sudden departure was because "our canoes returned from catching of goats, firing of guns as they came

towards us to give us warning... they had espied three sail of ships, which they conceived to be men-of-war coming about the island."4 The three vessels came into sight a half-hour later, resulting in the Trinity cutting her cables and sailing away "taking all our men

on board that were ashore at that time; only one William, a

Mosquito Indian, was then left behind upon the island, because

he could not be found at this our sudden departure."5

Among the men aboard the Trinity when this occurred was the ever-curious William Dampier, who also happened to be aboard buccaneer captain John Cook's vessel the Batchelor's Delight when it returned to the island and picked Will up in March of 1684. We know a great deal about Will's time on the island, thanks to Dampier's interest in and details about the life of this castaway.

Will turned out to be one of the more creative men stranded on the island. As Dampier relates,

He had with him his Gun and a Knife, with a small Horn of Powder, and a few Shot; which being spent, he contrived a way by notching his Knife, to saw the Barrel of his Gun into small Pieces, wherewith he made Harpoons, Lances, Hooks and a long Knife; heating the pieces first in the fire, which he struck with his Gun-flint, and a piece of the Barrel of his Gun, which he hardned; having learnt to do that among the English. The hot pieces of Iron he would hammer out and bend as he pleased with Stones, and saw them with his jagged Knife, or grind them to an edge by long labour, and harden them to a good temper as there was occasion.6

Dampier continues, "With such Instruments as he made in that manner, he got such Provision as the Island afforded; either Goats or Fish. He told us that at first he was forced to eat Seal, which is very ordinary Meat, before he had made Hooks: but afterwards he never killed any Seals but to make Lines [ropes], cutting their Skins into Thongs."7 He also made himself a hut, a barbeque made of sticks for roasting goats and fish and used goat skins to line his hut, make bedding and as makeshift clothing, wrapping it around his waist when his own clothing was beyond repair. Dampier's account of Will's solitary life on the island makes no mention him eating any of the edible plants while alone on the island, although he almost certainly did.

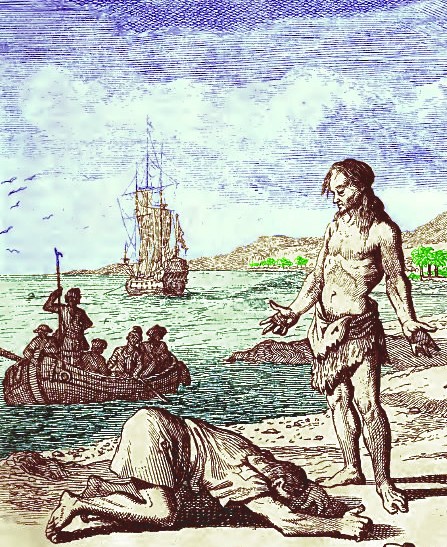

Artist: Caspar Luyken

Rescuing Will the Indian From Juan Fernandez, From W Dampier en

L Wafer Reistogten

Rondom de Waereld (1698)

A second account of Will's rescue is presented by William Cowley. He explains that "when he saw our Ships, presently fansied us to be English, and thereupon went and catch'd two Goats and dress'd them against our Men came on shoar"8. A third account, which is based on Basil Ringrose, notes that Will lit a fire to get their attention the day before they landed.9 Dampier's account of this is a little more expansive and differs slight in the details: "He saw our Ship the day before we came to an Anchor, and did believe we were English, and therefore kill'd 3 Goats in the Morning, before we came to an Anchor, and drest therm with Cabbage, to treat us when we came ashore."10 Here is an account of Will making use of the plants on Más a Tierra, specifically heart of palm (which was called cabbage in contemporary accounts). This suggests Will did eat the edible plants, although hearts of palm were notoriously hard to get, requiring the harvester to either climb to the top of the tree where it grows or chop the tree down to get at it. However, this information does not indicate that Will took trouble to plant things, rather only made use of what he found.

Dampier's account of his rescue by says Will came to greet the approaching boat at the shore (probably either in Cumberland Bay or Puerto Ingles). Dampier continues, "when we landed, a Moskito Indian, named Robin, first leap'd ashore, and running to his Brother Moskito Man, threw himself flat on his face at his feet, who helping him up, and embracing him, fell flat with his face on the Ground at Robin's feet, and was by him taken up also"11. Thus Will was rescued after three years and two months alone on the island.

The next temporary residents to be left at Isla Más a Tierra were several men who were aboard the Batchelor's Delight in 1687 after she had made several successful ship and colony captures during the three years after Will had been rescued. Captain Cook died in July of 1684 and the captaincy of the Batchelor's Delight

Dice-players gathered around a stone slab (c. 1620-30) was given to Edward Davis. Surgeon Lionel Wafer, who had been picked up by Davis in the summer of 1685, provides some detail of what happened to these men in in December of 1687. "Three or Four of our Men, having lost what Mony they had at Play [gambling], and being unwilling to return out of these Seas as poor as they came, would needs stay behind at John Fernando's, in expectation of some other Privateers coming thither."12 Dampier also mentions this group, stating that there were initially five of them, although one eventually surrendered to some Spanish sailors who had stopped at the island.13 In the account given of the Welfare, the ship which picked up these four men in February of 1690, sailor Richard Simson says that there were four Englishmen and their "four Boyes, whereof the Leader was a Negro".14 It is possible that the fifth man who left with the Spanish also had a boy, although Simson wouldn't have known of this.

These men appear to have been particularly poor gamblers because French buccaneer Ravaneu de Lussan mentions that Davis had previously stopped at Juan Fernandez on his way back to the Atlantic in April, but "the members of his crew who had lost their gold [at gambling] were unwilling to leave this sea and ship until they had acquired more plunder"15. So Davis sailed back up along the South American coast and spent another 8 months roving before deciding to return home a second time, depositing these five men and their boys on Juan Fernandez and making his way back to the Atlantic. From events in Simson's journal, we know the name of two of the men rescued: Harry and John Combs.16 Researcher Isaac James identifies the man who left with the Spanish as Mr. Cranston17, although the original source of this man's name isn't clear from James' text.

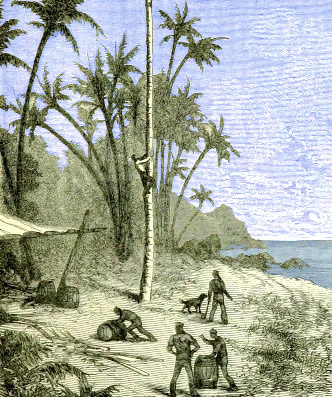

This little group of temporary settlers started off with quite a good deal of supplies and they seem to have been the

From Notable Voyagers from Columbus to Nordenskiold,

By

William Henry Giles Kingston (1885)

most proactive of all the sailors left on the island in developing its resources. Wafer says, "We gave them a small Canoa, a Porridge-pot, Axes, Macheats [machetes], Maiz, and other Necessaries."18 Simson adds that they also had "a Salt pan, and ...Hammers, Saw’s & other Iron Tools for felling of Trees, & building of Hulls."19 This wealth of tools likely explains why they were so active in developing the island to suit them. Simson even says that they had dug passages through the mountains and created 'lines of communication' using ropes when the Spanish landed to try and capture them.

Of particular interest to this discussion is the corn seed. Wafer said, "I heard since that they planted some of the Maiz, and tam' d some of the Goats, and liv'd on Fish and Fowls"20. Simson's account provides a wealth of detail on their lives on the island. He says that they had had three hundred tame goats in their stock at one point, although the Spanish showed up and robbed them of some of them.21 Wafer reported that their diet included "Turnipp-topps supplying their want of Bread, their ffood being [goat] Venison, their drink Goates milk and excellent water" seasoned by salt they "made ...by the Sea-Side."22 Historian Woodward takes the mention of turnip tops to suggest that they actively cultivated turnips.23 While this is possible, it is impossible to state with any certainty based on details found in Wafer's account. The islanders presented their life as being idyllic in an effort to try and convince Welfare captain John Strong that they were so happy there that he would have to add them to his crew and pay them to make them willing to leave. This failed and the four men finally "pulld off this Vaisard [mask] before we sayled from thence, and declared themselves glad to have the opportunity of seeing their owne Country once more, nay they plainly told us that they resolved to goe off the Island with the next Privateeere that should happen to victualing there."24

A letter written in 1704 mentioned that two French ships which stopped at Isla Más a Tierra and picked up five sailors and a slave left on the island by the privateer vessel

The Author Milking a Goat in His Period Garb

Cinque Ports' when it departed in a hurry on February 29, 1704.25 There were apparently two more men the French didn't find because when Alexander Selkirk was rescued by Woodes Rogers on Juan Fernandez in 1709, he said that "two [men] of the Ships [the Cinque Ports'] Company were left upon it [Más a Tierra] for six Months till the Ship return'd, being chas'd thence by two French South-Sea Ships."26 From this, we know that the Cinque Ports was at Juan Fernandez in July or August of 1704 and that there were probably seven men and a slave left on the island (along with water casks, cables, anchors and a boat). These remained because the captain was in a hurry to leave and chase a potential prize ship. Unfortunately, nothing of these sailor's impact on food cultivation is mentioned in any of the sources.

Yet another secondhand account of temporary settlers in the Juan Fernandez Islands talks about twenty French 'pirates' living there for ten months at some unknown period previous to 1703. William Funnell learned of this group from a Spanish captain named Christian Martin who explained that they landed on the western side of the island (probably at the most accessible point, Cumberland Bay). They "drew there [sic] little Armadilla ashoar and in a small time brought the Goats to be so tame, as that they would many of them come of themselves to be milked; of which Milk they made good Butter and Cheese, not only just to supply their Wants whilst they were upon the Island but also to serve them long after"27. Any group which could manage to produce goat's milk and cheese at Juan Fernandez likely made use of the fish and vegetables found there as well, although this is not specified in Funnell's retelling of the story.

This brings us to Isla Más a Tierra's most famous stranded resident, Alexander Selkirk. He was the sailing

Selkirk Left on the Island, From Notable Voyagers from

Columbus to Nordenski'old, By William H.G. Kingston (1885)

master of the Cinque Ports, which it arrived at the island in September of 1704. The ship had originally been captained by Charles Pickering who died early in the voyage, being replaced by Lieutenant Thomas Stradling.28 Stradling had been involved in several disagreements with his sailors, at one point causing eight of them to leave the ship before arriving at the Juan Fernandez islands. Further disagreements between the captain and men while at Más a Tierra required William Dampier to step in to ease tensions.29 Stradling was the man who decided to leave Selkirk behind after an argument with him.

Privateer Woodes Rogers, the primary source of Selkirk's time on the island, explains that there "was a difference betwixt him [Selkirk] and his Captain [Stradling]; which, together with the Ships being leaky, made him willing rather to stay here, than go along with him at first; and when he was at last willing, the Captain would not receive him."30 From this, authors often state the the argument was over the condition of the ships, although the 'difference' is mentioned in addition to this point. Dampier told Rogers that Selkirk was 'the best man' aboard the Cinque Ports, which, if true, doesn't speak very highly of Stradling's temperament. However, Selkirk also seems to have been fairly rough tempered, suggested two disagreeable men got into an argument which resulted in Selkirk being marooned by his superior.

Like the five former gamblers and their boys, Selkirk started his stay with a fairly impressive inventory. "He had with him his Clothes and Bedding, with a Firelock, some Powder, Bullets, and Tobacco, a Hatchet, a Knife, a Kettle, a Bible, some practical Pieces, and his Mathematical Instruments and Books. He diverted and provided for himself as well as he could"31. Sir Richard Steele claimed to have interviewed Selkirk for his newspaper The Englishman in 1711, shortly after Rogers' fleet returned to England in October. Steel added a few items to Selkirk's inventory including his Sea Chest (which belonged to the sailor, so this makes sense), a few pounds of tobacco, navigation instruments and a flint and steel.32 However, this would have been more than two years after Selkirk was rescued, so his recall may not have been as accurate then as what was related in Rogers' journal.

Selkirk's store of tools allowed him to build two huts from pimento trees and grass, one lined with goat's skins for living

A Fanciful Drawing of Alexander Selkirk's Hut, From A Universal Collection of

Authentic and Entertaining Voyages and Travels, Opposite p,86 (1765)

and sleeping and the other for slaughtering and dressing goat meat.33 Steele says that Selkirk told him the structures were by the side of a 'spacious wood' from which he cut down the trees to make them a "most delicious Bower, fann'd with continual Breezes, and gentle Aspirations of Wind"34. Edward Cooke of the Dutchess, Rogers companion ship, was far less impressed with these huts, describing route for reaching them as 'very much hid and uncouth' and being reached with 'much Difficulty', by climbing up and down rocks. Although, once there, Cooke says it was "a pleasant Spot of Ground full of Grass, and furnish'd with Trees", the two huts being neither well nor poorly built.35 Cooke also mentions that he had a "Spit [boucan] was his own handy Work, of such Wood as grew on the Island. His Bed rais'd from the Ground, on a Bed-stead of his contriving, consisted of Goats Skins, the rest suitable to the Habitation."36

Selkirk initially used his gun to kill goats, but he only had a pound of gunpowder so he had to conserve it as much as possible until he ran out. Rogers says that Selkirk became quite nimble as the soles of feet hardened once his shoes wore out so that "he ran with wonderful Swiftness thro the Woods and up the Rocks and Hills, as we perceiv'd when we employ'd him to catch Goats for us... [when chasing goats] he distanc'd and tir'd both the [ship's] Dog and the Men, catch'd the Goats, and brought 'em to us on his back."37 By Selkirk's ownn estimate, he had killed 500 goats for food, catching many others which he let go after marking their ear.

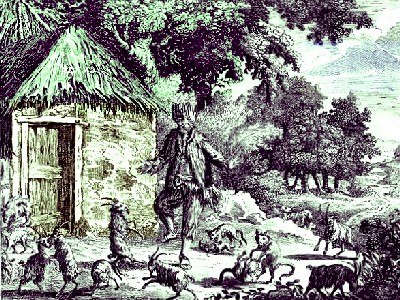

Selkirk Pester'd with Cats and Rats While Sleeping, From Providence Displayed,

By Isaac James, p. 71 (1800)

In the beginning of his stay, Selkirk found himself "much pester'd with Cats and Rats, that had bred in great numbers from ...Ships that put in there to wood and water. The Rats gnaw'd his Feet and Clothes, while asleep, which oblig'd him to cherish the Cats with his Goats-flesh; by which many of them became so tame, that they would lie about him in hundreds, and soon deliver 'd him from the Rats."38 Richard Steele says Selkirk told him he started with 'kitlings', which makes sense.39

Rogers also says, "tam'd some Kids, and to divert himself would now and then sing and dance with them and his Cats: so that... he came at last to conquer all the Inconveniences of his Solitude, and to be very easy."40 The difference between the wild goats Selkirk chased for food and possibly sport and the young kid goats he tamed and danced with hints at the tame goats being pets as much as food. Yet Steele says Selkirk intentionally lamed some kid goats so that they couldn't run very fast as a precaution "against Want, in case of Sickness"41. Cooke similarly notes that his house was surrounded by "a Parcel of Goats he had bred up tame, having taken them young, which serv'd to supply him upon Occasion when he fail'd of any wild."42 Whatever the case, Selkirk's actions suggest less in the way of taming goats than some of the other accounts, although more taming of the cats. (Then again, with cats, it is difficult to say whether we tame them or they us.)

He may have cultivated the plants he found on the island, for he certainly used them, although there isn't enough detail in Rogers' account to indicate this one way or the other.

Alexander Selkirk Falling on Goat, From Les Grands

Navigateurs du XVIIIe Siecle, By Jules Verne, (1885)In addition to turnips, Selkirk made use of heart of palm (referred to as cabbage) and parsnips, as well as seasoning including pimento and malagueta pepper.43 Curiously, he only ate fish in the beginning of his stay because he lacked salt (and for some reason he apparently couldn't make it) and they gave him diarrhea. He did eat the local lobster, which Rogers said was very good.44

Steele claims that Selkirk "found great quantities of Turtles, whose Flesh is extreamly delicious, and of which he frequently eat very plentifully on his first Arrival, till it grew disagreeable to his Stomach, except in Jellies."45 In fact, turtles are not found on Juan Fernandez so this may be incorrect.

Selkirk also gathered some "small black Plums, which are very good, but hard to come at, the Trees which bear 'em growing on high Mountains and Rocks."46 Given their location, it doesn't seem likely that he would have gone into the mountains to gather many of these because he had previously fallen from a precipice several feet while chasing a mountain goat, resulting in his laying there for a day (Steele says three days) and then crawled back to his hut where he was waylaid for further ten days.47 This is likely the point at which he decided to lame and tame some kid goats.

In many ways, Selkirk was fairly ingenuitive in adapting what he had. He made fires by rubbing pimento branches together on his knee.48 He stitched goat skins together to make clothing using "little Thongs of the same, that he cut with his Knife. He had no other Needle but a Nail; and when his Knife was wore to the back,

Selkirk Being Taken Aboard the Duke By Woodes Rogers, From Desperate Journeys, Abandoned Souls,

By Robert E Leslie,

(c. 1859)

he made others as well as he could of some Iron Hoops that were left ashore, which he beat thin and ground upon Stones."49 Using some linen he had among his supplies, he sewed shirts using the nail to pull worsted wool from his old socks through as thread.

Selkirk was rescued by Woodes Rogers little fleet on February 2nd, 1709, making his stay on the island about four years and four months. Rogers reported that in his goat's skin clothes he "look'd wilder than the first Owners of them."50 Having gone barefoot for so long, he couldn't wear shoes and having not spoken to another person for over four years spoke his words 'in halves'.51 However, he eventually acclimated to life among his peers. Based on Dampier's recommendation, Rogers agreed to give him a position aboard the Duke as sailing mate.

The next group of stranded sailors began with four men who deserted Captain John Clipperton's ship Success when he stopped at Más a Tierra on September 7th, 1719. Clipperton spent a month waiting for the Speedwell, his consort ship which was captained by George Shelvocke, but after a month he decided that something must have happened to Shelvocke on the way there.52

Hunting Goats on Juan Fernandez, From Providence Displayed,

By Isaac James, p. 111 (1800)

Two of these four deserters were caught by some of Clipperton's sailors who were hunting for goats on October 6th, the day before their ship left left. The two captured men provide the only insight into the manner in which the four men had survived up until that point, as found George Taylor's journal: "They told our men that for the first five days they were hard put to't, being forced to subsist wholly on the cabbage-trees, of which her is great plenty; but that having by good fortune one night found some fire that was left by our hunters, it served them in good stead, for they could then dress their fish and fill their bellies."53 These four men don't seem to have been nearly as resourceful as some of the previous stranded sailors.

Clipperton departed from the island on October 7th, leaving the two men they couldn't catch on the island. While at sea, he took a pink (a ship with a narrow stern) called the Rosary from the Spanish and put some of his men aboard her. The Spaniards on the Rosary managed to overpower his men, however, and they ran their former ship aground on November 20th somewhere near Lima, Peru. Upon questioning Clipperton's overpowered men, the viceroy of Peru learned "that two of Clipperton's men had deserted there upon which he immediately sends out a small vessel to fetch the two men."54 The exact date they were picked up isn't known, although it had to be before Shelvocke reached the island on January 12, 1720 in order to meet Clipperton. So the two deserters were probably only on the island for about two or three months and likely did little to develop the islands food sources.

The next group stranded were the privateers of the Speedwell. After failing to meet Clipperton, they left the island on January 15,

The Speedwell, From A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great

South Sea,

By George Shelvocke (1726)

1720 and raided the South American coast. Captain George Shelvocke decided to return to Isla Más a Tierra on May 11th of that year to get fresh water. He reports having trouble getting to the island when the ship struck rocks in the harbor in what he described as 'a dismal accident'.55 Sailor William Betaugh accused Shelvocke of intentionally wrecking the Speedwell, suggesting by way of proof that he made sure to immediately get the valuable and water-susceptible sugar and gun powder out of her along with their gold, money and commission. He didn't bother to remove the provisions from the hold, however.56 Betaugh says the men later recalled "how they had often heard him say, That it was not difficult living at Fernandes, if a man should accidentally be thrown there since Mr. Selkirk had continu'd upon it four years by himself."57 Betaugh makes several other good points to support the idea that Shelvocke sank the ship so that they could build another one and rewrite the articles of agreement so that the owners would lose their share. Although it must also be noted that Betaugh spends his entire book complaining about all of Shelvocke's actions during the trip, so his bias was notable.

Photo:Wiki User Serpantus - Cumberland Bay on Isla Más a Tierra aka Robinson Crusoe Island

Whatever reason the ship wrecked, Shelvocke's crew was stuck on the island between May 25th and October 6th. Although Shelvocke spends fifty-four pages of his book describing the island and their manner of living there, only a small part relates to the crew's methods of provisioning themselves.58 Unlike other temporary island inhabitants, Shelvocke didn't find the goats to be particularly useful as food because they were hard to catch. He explained that the Spanish had "endeavour'd to destroy the goats by leaving dogs, who are now very numerous; but the goats had the start of them so long, that it is very improbable to suppose they will ever be able to effect what the Spaniards intended, especially when one considers the many places of refuge they have, where no dogs can follow them."59

There were other sources of meat, of course. Shelvocke mentioned an abundance of cats which benefitted the sailors "whose stomachs preferr'd their flesh for food, have assured me, that their hunger found a more substantial relief from one meal of [a cat], than from 4 or 5 of seal or fish; and ... we had a small bitch which would catch almost any number they wanted in an hour or two."60

Fishing With Lines From A Boat, From Traite General des Pesches

By

Duhamel du Monceau, Plate 14 (1769)

As suggested, the castaways also made use of the fish and seals. Shelvocke explains, "At first the weather not permitting us to go a fishing for some time after we were cast away, necessity drove us to make use of seals; but could not, for a pretty while venture upon their flesh, and therefore began by their entrails, which are really palatable."61 By July, Shelvocke noted that his slave was killing seals and fishing for him.62 He explained that in September (when the group was making preparations to leave the island and the carpenter had built them a small vessel), "Our boat was daily employ'd in fishing, the Armourer constantly supplying them with hooks, and there was no want of lines, which were made of twisted ribbon, of which a great quantity was driven ashore"63.

For vegetables, this group doesn't seem to have done much in the way of cultivation, instead relying on the food that they could scavenge. "Some of the English that have been here formerly, sow'd turnips, which have spread very much, together with two or three small plantations of pumpkins; but my men had never patience to let any of these come to maturity; we likewise found plenty of water-cresses and wild sorrel."64 Nor does Shelvocke himself seem to have made any effort in this direction, mentioning that in the beginning of their stay his slave would bring back hearts of palm ('palm cabbage') from the mountains for him.65 In all, the four and a half months spent on the island by Shelvocke and his crew had limited impact on food cultivation there.

Because their ship wrecked close to the shore, the Speedwell's crew had access to quite a bit of hardware. As mentioned, Shelvocke had specifically saved the gun powder. They also managed to retrieve water-buts (barrels), rope, tents

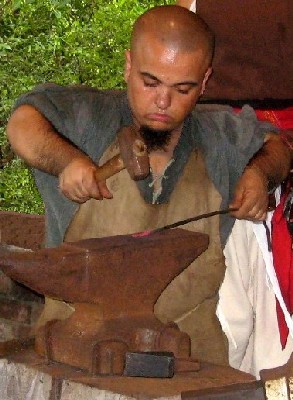

Photo:Author

Re-enactor Theo Alexander Working at a Primitive Forge

(likely made from the sails), small arms, lead (probably balls for use as small arms shot), musket-shot and axes and a pump.66 Shelvocke notes that they also had a "pitch-ladle, and covers of the ship's coppers [which] were converted into frying- pans"67.

The most competent and useful man among them seems to have been the Armorer, a Mr. Popplestone. In addition to the fish hooks, he "made us a little double headed maul [large hammer], hammers, chisles, files, and a sort of gimblets [hand tools for drilling holes], which performed very well; nay, he even made a bullet-mould, and an instrument to bore our cartouch-boxes, which we made of the trucks of gun-carriages which wash'd ashore... [which] enabled to perform any iron-work the Carpenter wante"68.

After finishing the boat they used for fishing, the carpenter and armorer began work on a small barque which they named Recovery. In preparation for sailing in this barque, Shelvocke conserved the few sea stores he recovered from the wreck of the Speedwell, including "one cask of beef, and 4 live hogs... with 3 or 4 bushels of Farina [which he elsewhere points out was actually cassava root flour]."69 Knowing this would be insufficient for a voyage of any length, they began experimenting with preserving fish and seal, but could not manage without salt. (Here again it is worth wondering why they hadn't thought to dry sea salt for this purpose using the pan lids.) Fortunately, they came up with a method of curing the conger-eels. They split them, took out the back bone, "then dipp'd them in salt-water, and afterwards hung them up to dry in a great smoke; but no other fish could be preserv'd after that manner, therefore the fishermen were order'd to make it their business to catch what congers they could"70. Their cooper was tasked with building barrels to hold the eels, presumably from the wood from the wreckage. The Recovery launched on October 6th with around forty men aboard.

This brings us to the last known group left on the Juan Fernandez Island during the golden age of piracy. There were many arguments among the crew of Speedwell

Small Vessel Leaving Juan Fernandez Islands, From 'Ile de Juan Fernandez',

Le Magasin Pittoresque, p. 189 (1842)

during the months they were stranded on the island and several factions emerged. One of these consisted of a dozen men "who accordingly separated from the rest, and never appear'd amongst us" except to steal things from them.71 When the newly built Recovery sailed, Shelvocke said they left behind "11 or 12 of those who had deserted us, who were deaf to all perswasions; and, in short, sent me word, that they were not yet prepar'd for the other world; so that they, with the like number of Blacks and Indians, remain'd on the Island."72 Betaugh says there eleven men along with 'thirteen Indians' (which Shelvocke had called blacks). He provides the names of the sailors: "John Wisdom, Joseph Monero, William Blew, John Riddleclay, Edmund Hyves, Daniel Harvey, William Giddy, John Robjohn, Thomas Hawkes, James Row and Jacob Bowden seamen."73 Because no account of them has been found, their supplies and impact on the island are unknown. According to historian Woodard, a Spanish force arrived on the island at some point before early 1722 and removed this group74. If correct, their time alone on the island wouldn't have been much more than a year.

Although the history of the Europeans left on Isla Más a Tierra in the Juan Fernandez islands through the end of the golden age of piracy makes for wonderfully colorful stories, the general impact of these sailor's actions on the food sources found there was relatively minor. Some of them made minor efforts to cultivate the crops and tame animals such as the cats and goats so that they might provide food or companionship, but they either knew or hoped they would not be on the island long enough to require extensive cultivation. All of their efforts would have been lost as the plants and animals gradually reverted to a wild state once they were gone.

1 Ralph Lee Woodward, Robinson Crusoe's Island, 1969, p. 19; 2 Woodward, p. 13-4; 3 Alexandre Exquemelin, The History of the Buccaneers of America , 1856, From the Section based on Basil Ringrose's South Sea Waggoner, p. 119; 4,5 Exquemelin, Basil Ringrose's South Sea Waggoner, p. 122; 6 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 84-5; 7 Dampier, p. 86; 8 William Ambrosia Cowley, "Cowley’s Voyage Round the Globe", A collection of original voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1993, p. 7; 9 Exquemelin, Based on Ringrose's South Sea Waggoner, p. 277; 10,11 Dampier, p. 86; 12 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 192; 13 Dampier, p. 86; 14 Richard Simson, Observations Made During a South-Sea Voyage, 1689, Quoted in Jonathan Lamb, Vanessa Smith & Nicholas Thomas, Exploration and Exchange: a South Season Anthology, 1680-1900, 2000, p. 34 & 36; 15 Raveneau de Lussan, Buccaneer of the Spanish Main and early French filibuster of the Pacific, Translated and edited by Marguerite Eyer Wilbur, 1930, p. 202; 16 Richard Simson, Observations Made During a South-Sea Voyage, 1689, Quoted in Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, pp. 26-7; 17 Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, p. 23; 18 Wafer, p. 192; 19 Simson, Quoted in Lamb et. al., p. 36; 20 Wafer, p. 192; 21 Simson, Quoted in Lamb et. al., p. 34; 22 Simson, Quoted in Lamb et. al., p. 35 & 36; 23 Woodward, p. 28; 24 Simson, Quoted in Lamb et. al., p. 35; 25 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 126; 26 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 49; 27 Funnell, p. 20; 28 Funnell, p. 12; 29 Funnell, p. 12 & 17-8; 30 Rogers, p. 125; 31 Rogers, p. 126; 32 Sir Richard Steele, The Englishman, Vol. 26, Dec. 3, 1712, 1714, p. 169; 33 Rogers, p. 126; 34 Steele, p. 170; 35 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, 1712, Vol. 2, p. xx; 36 Cooke, Vol. 2, p. xxi; 37 Rogers, p. 127; 38 Rogers, p. 128; 39 Steele, p. 172; 40 Rogers, p. 128; 41 Rogers, p. 127; 42 Cooke, Vol. 2, p. xxi; 43 Rogers, p. 127 & Cooke, Vol. 1, p. 37; 44 Rogers, p. 129; 45 Steele, p. 170; 46 Rogers, p. 126; 47 Rogers, p. 127 & Steele, p. 172; 48 Rogers, p. 128; 49 Rogers, p. 128; 50 Rogers, p. 125; 51 Rogers, p. 129; 52 William Betaugh, A Voyage Round the World, 1728, p. 87 & 89; 53 Betaugh, p. 89; 54 Betaugh, p. 97; 55 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 205; 56 Betaugh, p. 176-7; 57 Betaugh, p. 172; 58 See Shelvocke, pp. 204-258; 59 Shelvocke, p. 252; 60 Shelvocke, p. 251; 61 Shelvocke, p. 243; 62 Shelvocke, p. 228; 63 Shelvocke, pp. 239-40; 64 Shelvocke, p. 250; 65 Shelvocke, pp. 228; 66 Shelvocke, pp. 209, 211, 236, 241 & 242; 67 Shelvocke, pp. 245; 68 Shelvocke, p. 215-6; 69 Shelvocke, pp. 238 & 259; 70 Shelvocke, p. 238; 71 Shelvocke, p. 236; 72 Shelvocke, p. 242; 73 Betaugh, p. 234-5; 74 Woodward, p. 63