Juan Fernandez Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Juan Fernandez Islands Page 3

Juan Fernandez Ship and Provisioning History

The Juan Fernandez islands were uninhabited when the Spanish learned of them and, with the exception of the castaways and willing residents noted in the previous section, they remained that way until well after the end of the golden age of piracy. Due to this, the history of provisioning and development of provisions is inextricable from the history of the ships which stopped there and what they did while on Isla Más a Tierra. Although the majority of the recorded ship provisioning seems to have centered on that island, it is worth first taking a look at the other two islands which are part of the Juan Fernandez Archipielago.

Isla Santa Clara and Isla Más Afuera

Santa Clara Island in 1741, From View of Juan Fernandez Coast,

Illustrations de Voyage autour du monde (George Anson) (1750)

The small Isla Santa Clara, often referred to by the English buccaneers and privateers as 'Goat Island' is located about a mile southwest of Isla Más a Tierra. It is relatively barren with most of the original vegetation having been eaten by the goats which gave this island its seventeenth century English name1, although it is not clear when they were put there. The first English account of the little island is found in the Dutch landing of the Eendract and Hoorn under the command of William Schouten in 1616. In this account, the island is noted as " a very dry bare Island with nothing in it, but bare hilles and cliffes"2. Still, there must have been enough foliage to support a thriving goat community; Alexander Findley wrote that when HMS Collingwood was there in 1845 "Sta. Clara island was full of [goats] and here are more easily taken [than on Más a Tierra]"3, most likely because they were not as frequently disturbed, having far fewer visitors.

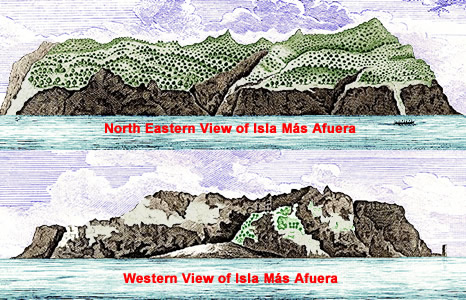

This brings us to the other large Juan Fernandez Island: Isla Más Afuera. Unlike Más a Tierra, it appears only once for certain in the period sailor's literature, perhaps because it was farther from the shores of Chile than the other two islands. Even the Spanish were reported to refer to it as 'the less' and Más a Tierra as 'the greater'.4 As with the other Juan Fernandez islands, it was stocked with goats by the Spanish at some unknown time, likely in the late 16th century. Basil Ringrose suggests that Bartholomew Sharp's Trinity stopped at the 'Westermost' island on December 24th, 1680 which we today would consider Más Afuera. However, the location given in his book (as near as it can be figured) sounds as if he was actually talking about Más a Tierra.5

Isla Más Afuera in 1741, From View of Juan Fernandez Coast, Illustrations de Voyage autour

du monde (George Anson) (1750)

Captain John Strong's ship Welfare landed at Más Afuera on February 4, 1690 while seeking Más a Tierra according to sailor Richard Simson's account of the voyage. Having come around the Horn, they were in need of re-provisioning so they stopped at Más Afuera, providing the only definite account of that island from European journals during the period of interest. He says that the sailors "brought off some Goats, killed some Fowls, and took some excellent Craw-Fish and Conjer-Eels."6 The island was clearly stocked with animals which could be used for food. Simson also mentioned finding two Crosses and 'a Cutlass a little damnified with

Rust', from which he concluded that the Spanish had been there recently, perhaps to get provisions and water.

After the golden age of piracy in 1741, Anson sent his expedition's eight gun sloop Tryal to visit Más Afuera to see what it offered. The officers on the Tryal reported that Afuera "was covered with trees, and that there were several fine falls of water pouring down its sides into the sea... it abounds with goats, who, not being accustomed to be disturbed, were no ways shy or apprehensive of danger... [as well as] vast numbers of seals and sea-lions"7. The account of Anson's voyage includes two lush views of Más Afuera (seen above left), noting that the Spanish had put no dogs on that island to kill the goats. This suggests that this was because the Spanish didn't think enough enemy ships stopped there to make it worth their effort. The author of the Anson account summarized the island thus: "though it was not the most eligible place for a ship to refresh at, yet in case of necessity it might afford some sort of shelter, and prove of considerable use, especially to a single ship, who might apprehend meeting with a superior force at Fernandes [Más a Tierra]."8

1 Tod F. Stuessy, Clodomiro Marticorena, Ulf Swenson, Josef Greimler and Patriciou Lopez-Sepulveda, 'Impacts on Vegetation' Plants of Oceanic Islands, 2017, p. 130-1; 2 Jacob Le Maire, The relation of a wonderfull voiage made by William Cornelison Schouten of Horne, 1619, p. 27; 3 Alexander G. Findlay, A Directory for the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean, Vol. II, 1854, p. 794; 4 Richard Walter, A Voyage Round the World, 1748, p. 156; 5 Basil Ringrose, The Voyages of Capt. Sharp, 1684, p. 48; 6 Richard Simson, Observations Made During a South-Sea Voyage, 1689, Quoted in Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, pp. 25; 17 Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, p. 23; 7 Walter, p. 156-7; 8 Walter, p. 157Isla Más a Tierra

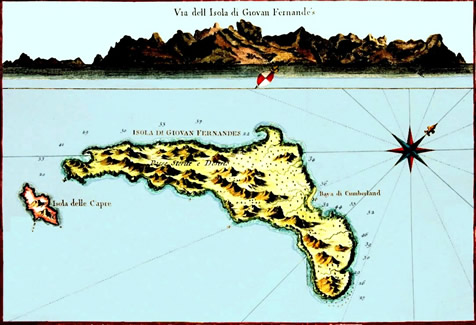

Nearly all of the known ship victualling action took place on Más a Tierra. Most of the animal and vegetable found there was put on the island by sailors. While there are indications that various sailors may have planted seeds on the island, it appears that the

Cartographer: Jacques-Nicholas Bellin - Map of Islas Más a Tierra & Santa Clara (1754)

two initial attempts to establish communities there by the Spanish in the late 16th century were responsible for much of the food available. There is even disagreement over whether vegetables suggested to be planted by non-Spanish sailors was originally Spanish in origin.

For example, when explaining how Alexander Selkirk survived on the island, Woodes Rogers writes, "in the Season he had plenty of good Turnips, which had been sow'd there by Capt. Dampier's Men, and have now overspread some Acres of Ground."1 Dampier was with Rogers, so he may have learned that the men aboard one of Dampier's ships landed on Más a Tierra had planted this crop. (These include the Trinity in 1681, the Batchelor's Delight in 1684 and 1685 and the St. George which was with the Cinque Ports in 1704.) However, Edward Cooke, writing about the same voyage says, it was the Spanish "who first inhabited the Island, [who provided vegetables] by leaving there the Seeds of Turnips, and several other Roots, which have since remained in the Ground."2 Based on how well the turnips had spread, author Isaac James agrees with Cooke that the vegetables were likely from the efforts of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century Spanish settlements.3

We have already seen how the Spanish established several colonies on the island with an eye towards living there, but a brief review is in order. The first community was organized by Sebastian Garcia Carreto in 1591

Artist: Theodor de Bry

A Native American Farm, From A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia (1590)

who is reported to have brought goats to the island.4 These colonists would likely have brought vegetable seeds as well since they appear to have been there for several years. The next colony was established by three Spanish entrepreneurs in 1599, consisting of "Indian colonists who had built homes and were cultivating vegetables"5. It is likely this community that historian and priest Diego de Rosales describes as building "houses of wood and straw for the farming of the land, [and who] brought and raised cattle"6, although he attributes the community's founding to Juan Fernandez. Other attempts were made to establish settlements there including a Jesuit community in the mid-17th century and French-run fishery in the early 18th, but none of these lasted very long. Even so, the wealth of sea-food found there appealed to the Spanish on the Chilean main land. "Mas-a-Tierra was visited fairly regularly by small ships from Valparaiso, which brought back to the mainland cargoes of fish, langosta [lobster] and oil from the seals and sea lions that inhabited the shores of the island in great abundance."7 A early seventeenth century author noted that "the Spanyards often times come thither to fish, and in short time fill their ships and carry them to Peru."8

The first non-Spanish sailors known to visit were William Schouten's men in the 220 ton,

William Schouten's Eendracht off Cocos Island Tonga, From The Relation of a

Wonderfull Voiage

made by Willem Cornelison Schouten of Horne (1619)

65 man Eendract and the 110 ton, 22 man Hoorn on March 1, 1616. Jacob Le Maire, son of the voyages' financial supporter Isaac, wrote a book about the journey in Dutch upon their return to Holland which was translated into English in 1619 as The Relation of a Wonderfull Voiage made by Willem Cornelison Schouten of Horne. Le Maire reported that the island was "full of very high hilles, but hath many trees, and very fruitfull. Therein are many beastes, as hogges, and goates, upon the coast admirable numbers of good fish"9. He notes that they couldn't land that day, but they were successful fishing; "in short time [they had] taken a great number of good fish, for the hooke was no sooner in the water but presently they tooke fish, so that continually without ceasing, they did nothing but draw up fish"10. The next day the ships' boats took some of the sailors ashore to retrieve water and hunt for meat. Le Maire said those remaining in the boats fished, taking in nearly two tons of fish, 'all with hooks'. The sailors who had landed "to seeke for cattell... saw many hogs, goates, and other beastes, but by reason that the woods were thicke they could not get them"11.

Historian Ralph Lee Woodward explains that "the publication of Le Maire's journal in 1618 made Juan Fernandez island known to the world, and it became thereafter a sought-after haven for navigators of all flags who entered the Pacific, but most particularly for those who would not find a welcome in the ports of Spanish America."12

Cartographer: Matthäus Merian der Ältere -

The Nassau Fleet off La Puná near Guayaquil (1630)

The next ships to make for Isla Más a Tierra were those of the Dutch Nassau Fleet under the command of Jacques Le Hermite. The Nassau Fleet consisted of eleven ships including six East Indiamen - the 300 ton Hollandia, 130 Ton Hoop, 350 ton Oranje, 400 ton Delft, 280 ton Mauritius and the 400 ton 42 gun Amsterdam; three war ships - the Fifth Rate 180 ton 16 gun Koning David, Fourth Rate 200 ton 28 gun Arend, Fourth rate 170 ton 22 gun Eendracht; the hired 80 ton 14 gun Griffioen and the 30 ton yacht Hazewind.13 The bulk of the fleet arrived at the island on April 5, 1624, followed by several of the vessels which had been separated while sailing around the Horn.

At full strength, this fleet would have had 1059 sailors and 495 soldiers, which was a made for a large number of men to be provisioned at the island. However, they seem to have managed. According to an English summary of the voyage translated by John Harris out of the original journal,

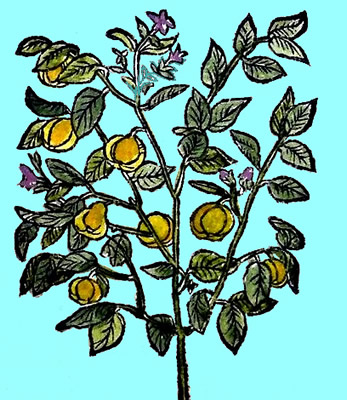

Artist: Leonhard Fuchs - Quince Tree (1551)

There cannot better Water be wished for, than is to be met with here; and excellent Fishing in the Bay of various kinds. There are many Thousands of Sea Lions, and Seals, that come daily out of the Water to sun themselves on shore, of which the Seamen killed Numbers, not for Food only, but for Diversion... Goats there are in great Numbers, but very hard to be taken; and they are not either so fat, or well-tasted, as those of St. Vincent [Sao Vicente, Brazil]. They found abundance of Palm-trees within Land [which they presumably chopped down to provide themselves with hearts of palm], and, near the Bay, Three large Quince-trees, the Fruit of which was very refreshing.14

Like Schouten's description of the island, this summary presents a vivid and enticing picture of the food available on the island. It is interesting that this voyage mentions quince trees being close to the bay where the ships landed, something no other voyage does. These may have been planted by a previous voyage and chopped down by the Spanish to prevent other travellers from benefitting from them. Whatever the case, this account would have been inspiring to the English buccaneer voyages the occurred in the later half of the 17th century. Yet the island isn't mentioned again in sailor's accounts until the last quarter of the century. This isn't to say no one stopped there, merely that the details of such visits were not published.

This brings us to the era of the buccaneers, the first of which to arrive on the island (as far as is known from the period books) was the Bartholomew Sharp's fleet led by his vessel Trinity, one of at least three ships in their little fleet.

In Sharp's journal, he

Cumberland Bay on Isla Más a Tierra, From Reize Rondom de Werreld (1765)

says, "We found it a very refreshing Place to us both in respect to the Goats we found here, whereof we salted about an hundred, and took as many on board alive, as to the fresh Water wherewith we filled our Vessels."16 The next day, an account based on that of Basil Ringrose, who was among the sailors, noted that Sharp sent "what men we could spare on shoar, to drive Goats, whereof there is great plenty in this Island. They caught and killed that day, to the number of three-score, or thereabouts."17 The goats were just the beginning, however. On the 28th, Sharp noted, "We met with great store of Fish, and particularly Lobsters, in this Place as also three Springs of good Water."18

Ringrose notes that once the men were sated "with Goats Flesh and fresh Fish, of both which here is plenty; and as it is usuall amongst the generality of men, that plenty of all things, breeds an increase of ill humors, Passion and Disturbances so it had the same effect upon our men, for now they are for a new Commander."19 As a result, John Watling was elected commander, deposing Sharp. On January the 12th, some of the men were out hunting goats on the opposite side of Más a Tierra, where Ringrose explains 'are found and caught the best' goats' when the men spotted three ships. Racing back to their own ships, they gave warning and the little fleet cut their anchors, leaving Will the native behind as they sailed away.20

The Batchelor's Delight under the command of Captain John Cook arrived at the island on March 22nd, 1684, remaining there for 16 days. They picked up the castaway native Will as detailed in the previous section and proceeded to

Artist: Thomas Murray - William Dampier (c. 1657-8)

water and victual their ship. William Ambrosia Cowley journaled the journey, noting that the sailors "found plenty of excellent fat Goats, good Fish, and abundance of very good Timber, with incomparable good Water. Here is such great plenty of Fish, that one Man may catch enough in a Days time to suffice 200 Men."21 Dampier notes that the island offered them cabbage (hearts of palm). He also talked about the goats which he claims Juan Fernandez himself put '3 or 4 Goats' on the island during his second voyage "which have since, by their increase,

so well stock'd the whole Island."22 Like other authors, he also mentions the seals, sea-lions and fish, of the last which he says they "are so plentiful,that two Men in an hours time will take with Hook and

Line, as many as will serve 100 Men."23 Interestingly, Dampier suggests that the island would be "capable of maintaining 4 or 500 Families, by what may be produced off the Land only. ...for the Savannahs would at present feed 1000 Head of Cattle besides Goats, and the Land being cultivated would probably bear Corn, or Wheat, and good Pease, Yams, or Potatoes, for the Land in their Valleys and sides of the Mountains, is of a good black fruitful Mould."24

John Cook died during the Batchelor's Delight's voyage and buccaneer Edward Davis was made captain. He returned in the ship to Más a Tierra twice, once in early December of 1686 and again in December of 1687, careening the Delight both times.25 Surgeon Lionel Wafer doesn't have a lot to say about the food found there, only noting on the second trip that the Spanish "had set Dogs ashore at John Fernando's also, to destroy the Goats there, that we might fail of Provision: But we were content with

Artist: Hendrick Van der Burg - Juan Fernandez Island [Isla Más a Tierra] (1840)

killing there no more than we eat presently"26. Upon sailing for Horn on their way back home, the five rueful gamblers discussed previously were left there with corn seed which Wafer mentions he heard they had planted. They ate fish and birds while stranded, something the sailors on the Delight may also have done even though Wafer doesn't go into that much detail.

The gamblers who remained on the island were picked up by captain John Strong and the sailors of the Welfare in mid-September of 1690. Although they victualled earlier in the month at Más Afuera, they didn't realize it was not Más a Tierra until they came across that island on September 11th while heading for the Chilean coast. Like other ships who stopped there, they sent their men ashore to get goats - the first two (along with a kid) were retrieved on September 12th with two more attempts after that which were not successful.27 Fortunately, "We had got [so] many before [at Más Afuera] as served our present turn."28 They took aboard other provisions thanks to the stranded gamblers who "did us singular Service in getting Provisions"29. What these provisions included isn't specifically explained, although the men on the island mentioned that they ate goat's meat and milk as well as turnip tops and they told the sailors they "might load the Ship with Goats if we pleased."30

An account mentions twenty French corsairs staying on the island for about ten months at some time before 1703.32 Little detail is given in the account of these men which is given second-hand by sailor William Funnel, although these French pirates clearly thought enough of the food and water to stay for such an extended period.

William Stradling's Cinque Ports arrived at the island in early February, 1704 where he was met by his consort the St. George captained by William Dampier on February 7th. Sailor William Funnell gives an account of this stop mentioning foods including heart of palm, peach palm berries, goats, fish, lobster (which he calls craw-fish) and seals, although he explains that they are 'not the best victuals'.33 Funnel provides a little more detailed information about some of the food they found which is discussed in the next section. On February 29th, the sailors saw some French ships approaching the island, so they

Artist: Theodor de Bry

Ships Passing an Island, From West Indianischer Historien Under Theil (1617)

cut their cables and ran, leaving their water butts, cables and other supplies, along with some men behind. A letter written in 1704 explained that the two French ships returned to Isla Más a Tierra, picking up the supplies and men left by the English buccaneers.34

After cruising the Pacific for several months and breaking off with the St. George which sailed across the Pacific to Guam and other points east, the Cinque Ports returned Juan Fernandez in July or August of 1704 on her way back around the Horn. Following an argument with his sailing master, captain Stradling left Alexander Selkirk on Más a Tierra.35 Although no details are supplied about their method of victualling during this second visit, they presumably got food similar to what Funnell listed during their first visit.

Selkirk's four year and four month stay gives a rare window into Spanish stops at the island. Selkirk told Woodes Rogers, "During his stay here he saw several Ships pass by, but only two came in to anchor. As he went to view them, he found 'em to be Spaniards, and retir'd from 'em; upon which they shot at him."36 To escape from the Spanish, Selkirk climbed a tree "at the foot of which they made water, and kill'd several Goats just by, but went off again without discovering him."37 It is notable that of the 'several ships' he saw pass by, only two Spanish vessels thought fit to stop at the island. This shouldn't be entirely surprising since many of the descriptions of vessels making landfall state that they would stay for several days if in a hurry and several weeks or even months if not. So stopping for food and water involved delays in a voyage and would likely only occur when absolutely necessary.

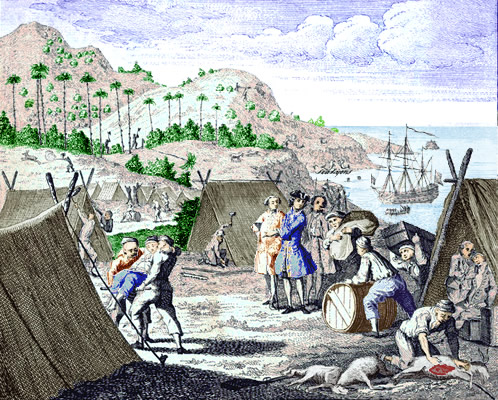

Rogers' ships Duke and Dutchess arrived at the island on January 31st, 1709. Three days after arrival, the crew set up a make-shift hospital for the sick, put the sail-makers to work mending sails, had the coopers make and repair casks, built a forge, set up tents "so that we have a little Town of our own here, and every body is employ'd."38 Among those 'employ'd', were sailors responsible for getting food and fresh water.

Artist: Hendrick Van der Burg

The Commodore at Juan Fernandez, From An Authentic and Genuine Journal of Commodore

Anson's

Expedition (1744)

Sailor Edward Cooke's account explains that upon their arrival, they "sent some Men shore to fish, and catch some of the wild Cattel. They found Plenty enough of Goats, and other such Creatures; but could take none, by Reason of the Woods."39 Fortunately, Selkirk had already cooked them two or three goats with hearts of palm as mentioned in the previous section. Selkirk continued to catch goats for them40, something he had become quite adept at doing. Rogers notes that Selkirk "never fail'd of getting us two or three Goats a day for our sick Men, by which with the help of the Greens and the Goodness of the Air they recover'd very fast of the Scurvy"41.

Like most other authors whose ships victualled at the Juan Fernandez islands, Cooke notes that the sailors "in a very little Time, took a great Quantity of excellent Fish, for as soon as ever they cast the Hooks into the Water, they drew them up again loaded."42 Rogers concurs, explaining that "A few Men supply us all with Fish of several sorts, all very good"43. He also mentioned that, upon their arrival, they sent out the ship's pinnace which "brought abundance of Craw-fish [lobsters]"44. They also killed sea-lions to get oil for use in their lamps and to cook with. The men working on the ship's rigging ate seals, although Rogers' text suggests that this behavior was limited to them.45

On February 11th, thirteen men went to the south end of island to capture goats because Selkirk said there would be an abundance of them. While there, they "surrounded a great parcel of Goats, which are of a larger sort, and not so wild as those on the higher part of the Island... but... they escaped over the Cliff: so that instead of catching above a hundred, as they might easily have done with a little precaution, they return'd this Morning with only 16 large ones, tho they saw above a thousand."46 They also tried eating some of the "Sea-Fowls in the Bay [which were] as large as Geese, but [they] eat fishy."47 They left the island on the 12th.

The next recorded visit to the island was by John Clipperton's ship Success which arrived on August 18th,

Capturing Goats, From Providence Displayed, By Isaac James, p. 22 (1800)

1718 to wait for his missing companion ship, the Speedwell captained by George Shelvocke. He stayed a month. The only record of his stay is a journal by George Taylor quoted in William Betaugh's book. It provides little information about the food on the island. On August 14th, Taylor says "This day our boats bring eighteen goats aboard: sent ashore for some salt; our men having found here a good quantity ready made, which was left by some of the French ships who often touch here."48 This is interesting in that it suggests French ships regularly stopped at the island during this period. In presenting the account of the four deserters mentioned in the previous section, Taylor identifies a group of men as being 'goat-hunters' on October 6th, suggesting a party of men went regularly to fetch goats for the ship. The next day Taylor provides the only other mention of food sought by the sailors on the Success: "Salted more fish, and brought off four cask more of seal."49 This indicates that there may have been instances of salting fish and killing seals for oil in Taylor's account which Betaugh doesn't quote.

Shelvocke showed up in the Speedwell on January 12, 1720, but they didn't anchor by the shore until the 15th. Shelvocke says that during those three days, they kept "the boats ...employ'd in catching fish, of which we salted as much as filled five puncheons [a cask holding about 72 gallons]."50 They don't seem to have spent a lot of time on the island, leaving on the same day they landed. At that time, Shelvocke remarked, "with the additional stock of fish caught here, [we were] in a pretty good condition as to provisions, and having all our water-casks fill'd."51 They returned to the island five months later, wrecking the Speedwell in the bay which resulted in their being castaway for four and a half months. During this time, the armorer and carpenter built a new craft from the wreckage of the old one which they named Recovery. The new ship had to be provisioned as well they could manage with the supplies on hand, all of which was described in some detail in the previous section.

The last recorded ships to stop at Juan Fernandez was the small fleet of Jacob Roggeveen who were trying to find the

Fishing at Juan Fernandez Islands, From Magasin Pittoresque, p. 189 (1842)

fabled 'southern continent'. This consisted of three vessels: the Arend (Eagle), Thienhoven and Afrikaansche Galey (African Galley), which were initially manned with 223 men.52 They arrived at the Juan Fernandez islands on February 24, 1722 where they stayed until March 17th.

As soon as they had Anchored, they sent their shallops (small boats) ashore with those sick with scurvy and went looking for Provisions and Refreshments. Roggeveen's log talks about the food on the island, although much of what he has to say is now familiar from the other accounts already cited. He stated that the fish "are so abundant, that four men with a hook and line can catch enough for 100 men in two hours to feed them lunch and dinner."53 He noted that most of these fish were spotted. He also talked about two vegetables they found there, the names of which were difficult to translate from Dutch. John Campbell, who gives an English summary of Roggeveen's journal says they included "Mustard-seed and Turneps, but complains that the latter were very bitter."54 However, in attempting to translate the original text, the author came up with cabbage rather than mustard-seed, which would seem to indicate that Roggeveen was referring to the now familiar heart of palm. He also talks about chasing goats - both male and female - noting that it was dangerous because they ran for the mountains when chased.55 He says that there are other provisions on the island, suggesting that the reader refer to Woodes Rogers and William Dampier's books for additional information.56

1 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 127; 2 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, Vol. II, 1712, p. xxii; 3 Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, p. 78; 4 Ralph Lee Woodward, Robinson Crusoe's Island, 1969, p. 4; 4 Ralph Lee Woodward, Robinson Crusoe's Island, 1969, p. 12; 5 Woodward, p. 8; 5 Diego de Rosales, Historia general de el reyno de Chile, 1877, Translated by the author, p. 284; 7 Woodward, p. 13-4; 8,9 Jacob Le Maire, The relation of a wonderfull voiage made by William Cornelison Schouten of Horne, 1619, p. 27; 10,11 Le Maire, p. 28; 12 Woodward, p. 17-8; 13 Holldandia, Hoop, Oranje, Delft, Mauritius, Amsterdam, Koning David, Arend, Eendracht, Griffioen & Hazewind, threedecks.org, gathered 6/16/20 & James Bander, Dutch Warships in the Age of Sail 1600-1714, 2014, p. 128; 14 John Harris, Navigantium atque Itinerantium Biblioteca, A Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels, 1744, p. 72; 15 Bartholomew Sharp, "Captain Sharp's Journal", A Collection of Voyages, Vol IV, 1729, p. 71; 16 Sharp, p. 44; 17 Basil Ringrose, ‘Containing the dangers Voyage and bold Assaults of Captain Bartholomew Sharp’, Bucainers of America, 1684, p. 116; 18 Sharp, p. 72; 19 Basil Ringrose, The Voyages of Capt. Sharp, 1684, p. 48-9; 20 Ringrose, Bucainers of America, p. 121-2; 21 William Ambrosia Cowley, "Cowley’s Voyage Round the Globe", A collection of original voyages, William Hacke, ed., 1993, p. 7; 22,23,24 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 88; 25 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 179 & 191; 26 Wafer, p. 192; 27 Richard Simson, Observations Made During a South-Sea Voyage, 1689, Quoted in Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, pp. 26 & 28; 28 Simson, p. 28; 29 Simson, p. 27; 30 Simson, p. 26-7; 31 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 126; 32 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 20; 33 See Funnell, pp. 18-24; 34 Rogers, p. 126; 35,36,37 Rogers, p. 125; 38 Rogers, p. 131; 39 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, 1712, p. 100; 40 Rogers, p. 127; 41 Rogers, p. 131-2; 42 Cooke, p. 100; 43 Rogers, p. 131; 44 Rogers, p. 125; 45 Rogers, p. 132; 46 Rogers, p. 133; 47 Rogers, p. 131; 48 William Betaugh, A Voyage Round the World, 1728, p. 88; 49 Betaugh, p. 89; 50 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 159-60; 51 Shelvocke, p. 160; 52 "Jacob Roggeveen, 1659–1729", lib-dbserver.princeton.edu, gathered 6/18/20; 53 Jacob Roggeveen, Dagverhaal der ontdekkings-reis van Mr. Jacob Roggeveen, 1838, interpreted from Dutch by the author, p. 89; 54 John Campbell, "An Account of Commodore Roggewein’s Expedition", Navigantium atque itinerantium bibliotheca, or, A complete collection of voyages and travels, 1744, p. 264; 55 Roggeveen, p. 89-90; 56 Roggeveen, p. 89