Juan Fernandez Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Juan Fernandez Islands Page 4

Juan Fernandez Food Descriptions

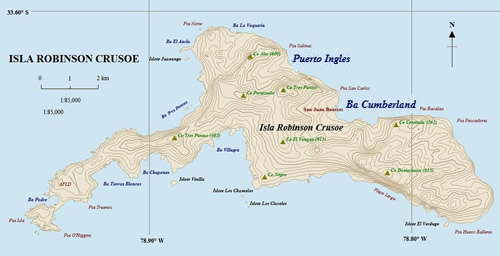

A Modern Map of Isla Más a Tierra With Named Locations on the Island

Unlike many of the English-held Caribbean islands, no books from this period were found which explained the plants and animals found on the Juan Fernandez Islands during the period under study. Being such an unusually helpful location for many of the European buccaneers and privateers, however, some of the men who visited it took the time to provide information on what they found in the way of provisions. The majority of these accounts spend their time describing the fish in the bays, the seals and sea-lions found on the beaches as well as talking about (but not really describing) the goats which roamed the land and eventually moved into the mountains. The only edible vegetation given much notice in these books were the 'cabbages' which refer to hearts of palm.

Fruit and Plants

c.jpg)

Photo: Author - Puerto Ingles, Robinson Crusoe Island (Más a Tierra)

In his history of Chile, Diego de Rosales commented, The largest [island, Más a Tierra] is fruitful, shaded by high jungles, bathed with cheerful fountains and streams that stand out from various hills. It is three leagues long, and six around... Many palms, angelino, sandalwood and other trees of useful wood grow"1. The Juan Fernandez Islands were pleasant and fruitful to the things which grew there, although indiginous plants Europeans found edible seem to have been quite limited. Other than hearts of palm and the berries found high in the mountains, the majority of the land-based meat and edible plants appear to have been brought to the island by the Spanish. Only two fruits and a handful of vegetables appear in the sailor's accounts.

The first fruit were from quince trees found growing by the shore by Dutchman Jacques le Hermite's Nassau fleet in April of 1624. These were likely the same sort found growing in Europe because the author only notes them as being "very refreshing" without bother to provide any detailed description of them.2 The presence of quinces is not mentioned in any other account, including the previous visit by William Schouten's crew in 1618, although their convenience and use by Le Hermite's crew is clear enough. It is possible that someone in Schouten's crew planted them or dropped the seeds there when they were there; quince trees can begin producing fruit when grown from a seed in

Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture - Pupunha, Bactris Gasipaes

as little as five years. However since they are not mentioned by any account following Le Hermite, these trees may have been chopped down by the Spanish to prevent their use by invaders on the western coast of South America.

The other fruit mentioned is variously called a "small black Plums"3 or "bunches of red berries"4 found on some palm trees up in the mountains. Sailor William Funnell explains that at the bottom of these trees (Bactris gasipaes) "grow great Bunches of Berries, of about six pound weight, in the shape of a bunch of Grapes. Their Colour is red like a Cherry; and the Berries are about the bigness of a black Cherry, with a large stone in the middle; and they taste much like English Haws [hawthorn berries]."5 George Shelvocke states that the trees look like Coconut trees, "except that the leaves of them are of a paler green, and bear large bunches of red berries bigger than a sloe."6 He also says that they taste like haws and have a large pit in the middle.

According to another version of the stop by the Nassau Fleet, the valleys on the Northeastern side of the island "were covered with herbage, and the fresh water was excellent."7 This basically refers to Cumberland and Ingles bays, two lush areas which were fairly accessible from the water where ships typically stopped. When the Wager stopped at Isla Más a Tierra in September of 1689, sailor Richard Simson wrote that the land was "woody, and bears and Excellent Herbage; Turnipps, Sorrill, and Cabbage trees... and [it is] very plentifull there"8.

Raw Palm Hearts Removed from the Tree

Woodes Rogers arrived in February of 1709, nothing that they "found Store of Turnip-Greens, and Water-Cresses in the Brooks, which mightily refresh’d our Men; and cleans’d ‘em from the Scurvey"9. Another plant mentioned is corn planted by the five unlucky gamblers who occupied the island from 1687 to 1690.10 Corn doesn't feature in any other account, however, so if it grew during that period it must not have continued to regrow afterwards, possibly because it was attacked by parasites or eaten by rats.

Every account mentions the presence of 'cabbage' - of which there appear to be two types mentioned. The first are the leave of the Dendroseris litoralis palm, also called the Juan Fernandez cabbage tree. William Dampier states that the palms he found on Más a Tierra in 1684 "are but small and low; yet afford a good head, and the Cabbage very sweet."11 The key here is that the plants were low, which is true of the Dendoroseris litoralis palm.

The other type of 'cabbage tree' is quite different. Basil Ringrose, who was on the island in 1681, talks about 'Bilby-trees', explaining, "The tops of these trees are excellent Cabbage, and of them is made the same use that we do of Cabbage in England."12 In 1709, Rogers stated that the trees "abound about three miles in the Woods, and the Cabbage very good; most of 'em are on the tops of the nearest and lowest Mountains. ...The Soil is a loose black Earth, the Rocks very rotten, so that without great care it's dangerous to climb the Hills for Cabbages"13. Similarly, in the summer of 1720, Shelvocke's marooned crew observed that "Palm-cabbage was very acceptable when we could get it which we never did without much trouble"14 The reference to the 'tops' of the trees and the difficulty of procuring the 'cabbage' is telling. Combined with a comment by Simson, that the cabbage trees were 'of a prodigious height' it sounds that these sailors were after what is today called heart of palm, which can be found on this island in the Juania australis tree.

Photo: David Armstrong

Turnips With Greens, River Medway, geograph.org.uk,

William Funnell, who visited Más a Tierra in 1704, describes heart of palm as being "at the top [of the tree]; in the midst of which, the Cabbage is contained; which when boiled is as good as any Garden-Cabbage I ever tasted. …The Cabbage when it is cut out from amongst the bottoms of the Branches, is commonly about six Inches about, and a foot long; some more, some less; and is as white as Milk."15 Shelvocke also described the process of retrieving the edible heart, saying that the top of the tree was "cut off, and dismember'd of its great spreading leaves, and all of it that is hard and tough, [then] you find enclosed a white and tender young head"16. He went on to complain that "the whole tree seldom affords above two pound that is eatable."17

Rogers is the only author up until the end of the golden age of piracy to provide any detail about one of the other vegetables. He states that "the Turnips, Mr. Selkirk told us, are good in our Summer Months, which is Winter here; but this being Autumn, they are all run to Seed, so that we can't have the benefit of any thing but the Greens."18 This may explain why the five gamblers discussed previously who chose to remain on Más a Tierra had "Turnipp-topps supplying their want of Bread"19, but don't mention the turnips themselves. Although he landed on the island after the period of interest in 1741, George Anson also provided some detail on the vegetables the crew found there:

Photo: Wiki user Rasbak - Growing Radish raphanus sativus

...here we had great quantities of watercress and purslain, with excellent wild sorrel, and a vast profusion of turnips and Sicilian radishes [Radish raphanus sativus - what many think of as radishes]: These two last, having some resemblance to each other, were confounded by our people under the general name of turnips. We usually preferred the tops of the turnips to the roots, which were often stringy; though some of them were free from that exception, and remarkably good.20

Richard Walter, the author of this account added that the soil was particularly good for many types of vegetation, "for if the ground be any where accidentally turned up, it is immediately overgrown with turnips and Silician radishes; and therefore Mr. Anson ...for the better accommodation of his countrymen who should hereafter touch here, sowed both lettices, carrots, and other garden plants, and sett in the woods a great variety of plumb, apricock, and peach stones"21. Wilson added that he had heard these plants thrived on the island, although, if true, their appearance was far too late for our sailors to enjoy.

1 Diego de Rosales', Historia general de el reyno de Chile, 1877, p. 284-5; 2 John Harris, Navigantium atque Itinerantium Biblioteca, A Complete Collection of Voyages and Travels, 1744, p. 72; 3 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 126; 4 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 249; 5 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 19; 6 Shelvocke, p. 249; 7 James Burney, A Chronological History of the Voyages and Discoveries in the South Sea, Part III, 1813, p. 18; 8 Richard Simson, Observations Made During a South-Sea Voyage, 1689, Quoted in Isaac James, Providence Displayed, 1800, pp. 26; 9 Rogers, p. 134; 10 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 192; 11 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 87;12 Basil Ringrose, ‘Containing the dangers Voyage and bold Assaults of Captain Bartholomew Sharp’, Bucainers of America, 1684, p. 122; 13 Rogers, p. 135; 14 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 245; 15 Funnell, p. 18-9; 16 Shelvocke, p. 249; 17 Shelvocke, p. 245; 18 Rogers, p. 135; 19 Simson, Quoted in Lamb et. al., p. 35; 20 Richard Walter, A Voyage Round the World - George Anson, 1748, p. 117; 21 Walter, p. 118

Fish

Fish were repeatedly mentioned as being the easiest provision to get for provisioning ships at the Juan Fernandez Islands during

Men Fishing, From The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert, Vol 8,

Plate 25 (1771)

this period. The first Dutch account of the island in 1616 says that there were "good fish of different kinds, and in such abundance, that scarcely was the hook half a foot deep in the water before the fish would fight for the bait."1 In an account of the first recorded buccaneer visit, the author says "on the surface of the water I have taken fish with a bare and naked hook, that is to say, unbaited. Much fish is taken here of the weight of twenty pound; the smallest that is taken in the Bay being almost two pound weight."2 Just after the golden age of piracy in 1741, sailor Richard Walter said it was still the case. "At the Island of Juan Fernandes you may likewise save a good quantity of fish, which you may catch with hooks although there is no convenience for hauling the seyne [dragging a net behind a rowed boat]; of these [fish] you may salt and save a good stock in a little while"3.

Before proceeding to describe the fish which were caught at the island, it is important to understand the difference between the fish found around the these islands and those which the European sailors were familiar with found in the the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Most of the contemporary sailor's accounts call the fish by names they were familiar with even though they are today recognized as very different species. The more observant sailors would call the fish by the names of fish they knew which most closely resembled them and then discuss the features of the fish found here which were different from the fish named.

Photo: Richard N. Home - Fishing in Cumberland Bay, Robinson Crusoe Island

Researchers who have studied the fish found in the Juan Fernandez Archipelago explain that the number of unique fish species found around Robinson Crusoe Island [Isla Más a Tierra] is extraordinarily high - around 87.5% being regionally endemic fish in one study. In addition, 99% of the total number of fish found there were endemic to the islands.4 Another study explains that the fish found there are "a composite of subtropical eastern and western Pacific, southwestern Atlantic, and southern Australia-New Zealand subantarctic faunas."5 The first study concurs, explaining that even though Más a Tierra is only a couple of hundred miles from the coast of Chile, "the Juan Fernández biogeographic province is considered a distinct ecoregion, with a strong southwest Pacific component to its marine fauna."6 Although these studies occurred three hundred years after the period under study, it is likely that the fish found at Juan Fernandez in the past were more representative of what they found than the types of fish found in the Atlantic Ocean since the ocean currents would have been largely the same then as now.

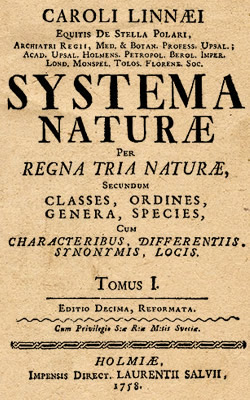

Naturally, determining which fish were which is difficult given the variety of fish which

Systema Naturae Cover, 10th edition (1758)

were called by the same name during the golden age of piracy. The system in use today wasn't even publicly proposed until Carl Linneas published his book Systema Naturae in 1735 and wasn't fully developed until the 10th edition of that book in 1758. Even if the system had been available to sailors before the golden age of piracy, it is doubtful that they would have made use of it. Many of the names given to fish by sailors arose from the appearance of the fish. For example, Walter lists a variety of fish they caught which included cod, "cavallies, gropers, large breams, maids, silver fish, congers of a peculiar kind, and above all, a black fish which we most esteemed, called by some a Chimney sweeper, in shape resembling a carp."7 Although the source of many of these words are a somewhat vague, 'cod' is suggested to have come from Old English cod(d) meaning ‘bag’8, cavalli from the Latin word for horse, while bream appears in several languages, and in at least one case suggests a Germanic word meaning sparkly and glittery.9 These terms are hardly accurate or scientific, either. Even today, cod is used to refer to all the species found in hake and pollock families, haddock (the family of the 'true' cod) and even ling.10

In an effort to try and identify the type of fish which the mariners may have been talking about, the author examined images for the generic sailor's named fish and compared them with those discussed in Bryan Dyer and Mark Westneat's, Taxonomy and biogeograph of the coast fishes of Juan Fernandez and Desventuradas islands, Chile. This paper contained photos of the fish they caught when researching the topic and, combined with other images of fish they identified but didn't photograph, a comparison was made to the generic fish named by sailors. The commonality of the fish as described by Dyer and Westneat was also considered, relying primarily on fish they suggested were often found at Robinson Crusoe Island. While inexact, this provided a list of fish which appear most likely to be what the period sailors might have caught.

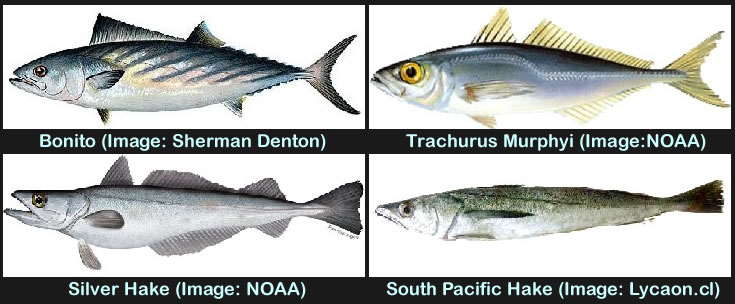

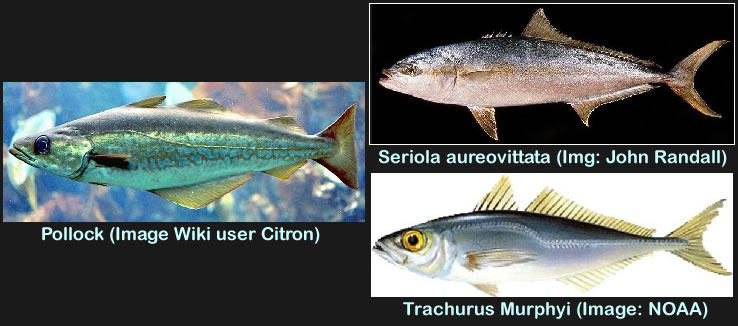

Talking about fishing in the Cumberland Bay in February, 1709, Edward Cooke provides a list of fish they caught there which includes two fish which only he mentions in his text: bonitos and hakes.11 The bonito might have been Trachurus murphyi and the hakes were almost certainly a form of South Pacific hake common to the area called Merluccius gayi gayi.

Comparison of Images of Bonito & Trachurus Murphyii and Silver Hake and South Pacific Hake |

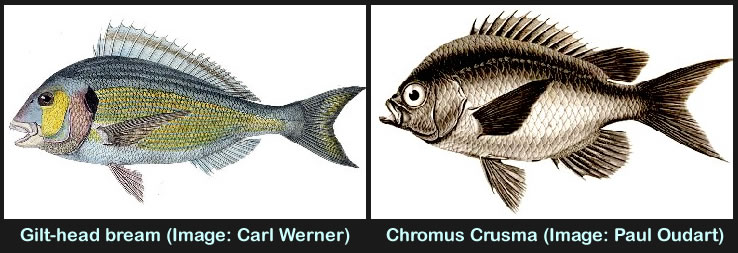

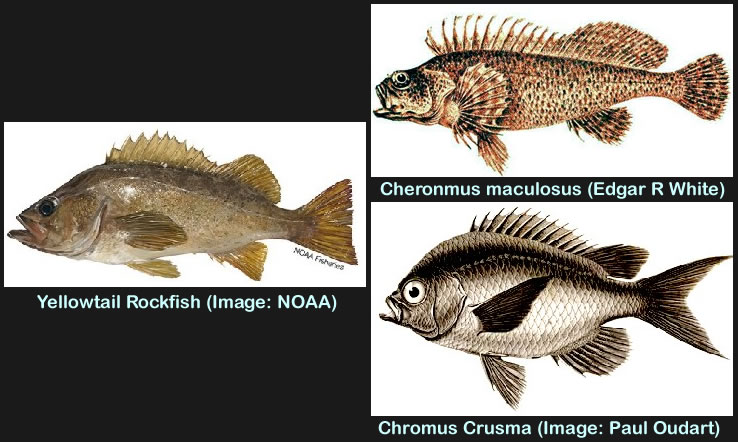

Several sailors talk about breams, which may have been Chromis crusma or the far less common Chromus meridiana. The account of Dutchman Jacob Le Maire's stop in 1616 talks about the most specific type of bream: gilt-heads.12 Sailor William Funnel lists breams among the fish he saw when at the island in 1704.13 Cooke mentions fish of a "Sort like Breames"14, indicating they were not like the breams he was used to seeing. While shipwrecked on Más a Tierra in the summer of 1720, George Shelvocke listed several fish they caught which included bream.15

Comparison of Images of Guilt-head bream and Chromus Crusma |

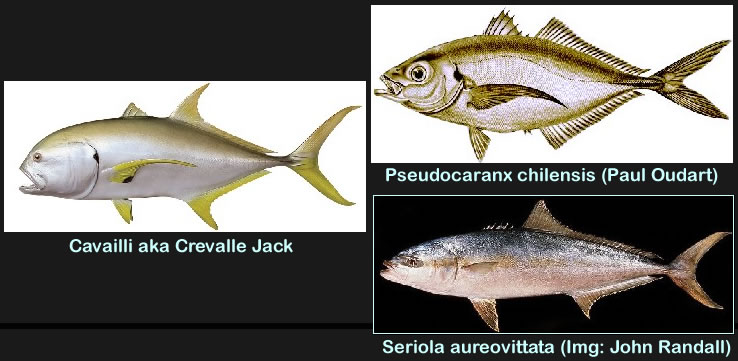

Cavalli, also called crevalle jacks, appear in several accounts as well. None of the fish found in Dyer and Westneat have a face like the cavalli, although the Pseudocaranx chilensis and Seriola lalandi have somewhat similar profiles so they might have been what the sailors meant. Sailor Richard Simson recorded the Welfare's boat catching "about 200 lusty Cavalloes "while fishing in September of 1689.16 Funnel in 1704 and Cooke and Woodes Rogers on the 1712 privateer voyage of the Duke and Dutchess also mention 'Cavallos'17 in their lists. Shelvocke lists 'cavally' among the fish they caught, explaining that the fish found there "the most exquisite in their kind".18

Comparison of cavalli to Pseudocaranx chilensis and Seriola aureovittata (No usable images of Seriola lalandi were found) |

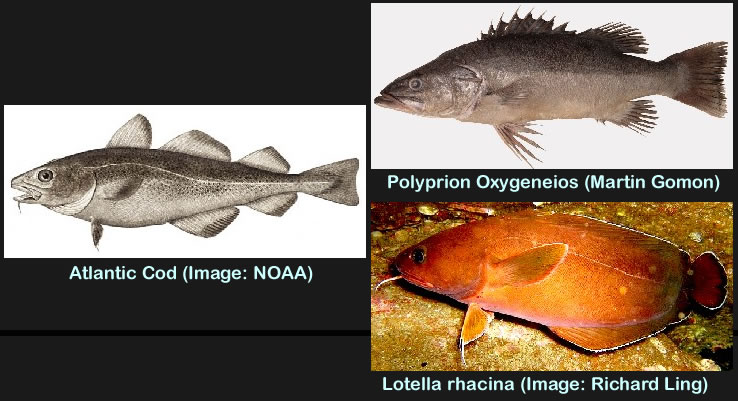

Shelvocke says that they caught cod.19 Richard Walter explains that during Anson's 1741 visit "we found here cod of a prodigious size; and by the report of some of our crew, who had been formerly employed in the Newfoundland fishery, not in less plenty than is to be met with on the banks of that island."20 These might have been Polyprion oxygeneios or possibly even Lotella fernandeziana.

Comparison of cod to Polyprion Oxygeneios and Lotella rhacina (No usable images of Lotella fernandeziana were found) |

Both Jacob Le Maire and Edward Cooke said that there were a lot of 'corcobado' (cocovado aka Caranx lugubris) in Cumberland Bay.21 These may have been Pseudocaranx chilensis.

Comparison of Corcovado (Caranx lugubris) to Pseudo caranx chilensis |

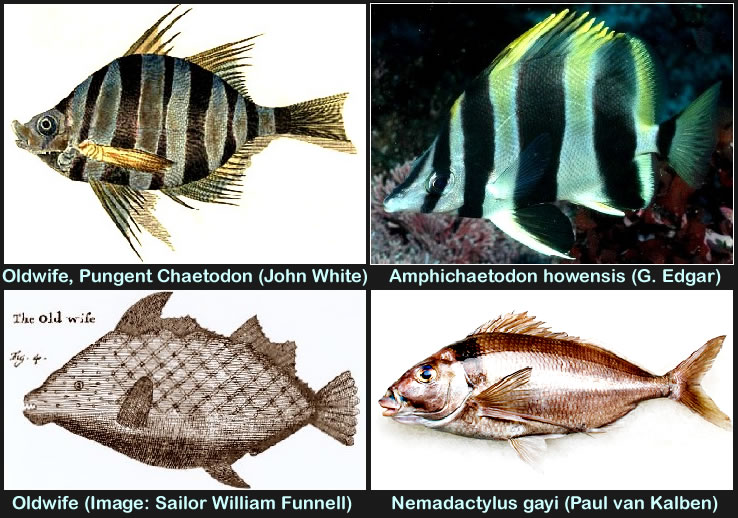

Cooke and Rogers are the only two authors to mention a couple different types of fish. These include oldwives22, which may have been Amphichaetondon melbae or, less likely, Nemadactylus gayi. (The juvenile Namadactylus tends to look more like a typical oldwife than the adult.) Although Funnell doesn't count oldwives among the fish he saw in the Juan Fernandez islands, he does draw an image of one in his book which is included here.

Comparison of oldwife to Amphichaetodon howensis and Namadactylus gayi. ((No usable images of Amphichaetodon Melbae were found) |

Cooke and Rogers also mention pollock, which might be a Seriola aureovittata or Trachurus Murphyi.

Pollock to Seriola Aureovittata and Trachurus Murphyi Comparison |

Photo: Daniel Ore Villalba - "Chimney Sweeper" Fish, Paralichthys adspersus

An interesting fish only mentioned in the later accounts were something referred to as 'chimney sweepers'. Shelvocke describes them as 'a black fish', explaining the reason for the name they were given.23 Some of the sailors on George Anson's voyage in 1741 must have read Shelvocke's book because they decided to call 'a black fish which we most esteemed' chimney sweepers, noting that they were similar in shape to carp.24 These are almost certainly Paralichthys adspersus fish; Dyer and Westneat note that these are an 'incidental species' which come from the Chilean coast, suggesting that they might not always be found in the Juan Fernandez archipelogo.25

Dampier only discusses a few of the fish found on Juan Fernandez Islands. One which he highlights during his visit in March of 1684 is the rockfish. He explains that they "are so plentiful, that two Men in an hours time will take with Hook and Line, as many as will serve 100 Men."26 Both Cooke and Rogers include rockfish in their lists as well.27 Dampier describes them as being "called by Sea-men a Grooper; the Spaniards call it a Baccalao, which is the Name for Cod, because it is much like it. It is rounder than the Snapper, of a dark brown Colour; and hath small Scales no bigger than a Silver-penny. This Fish is good sweet Meat, and is found in great plenty on all the Coast of Peru and Chili. Cooke and Rogers also list them among the fish taken by the crews of the Duke and Dutchess.28 The variety of names which this fish was called by various sailors according to Dampier indicates how confusing the fish of this area must have been to contemporary sailors. In fact, 'Grooper' is the same term used by William Funnel in his book recording Dampier's visit in 1704.29 Even today, the term 'rockfish' is just a term for fish who like to hide among rocks and includes a wide variety of fish. Based on Dampier's description of them, the rockfish he saw were probably a Chromus crusma or possibly a Chironemus bicornis.

Rockfish to Cheronmus and Chromus Comparison. No Cheronmus bicornus Images Were Found, Although the Muculosus Here is Colored Like One |

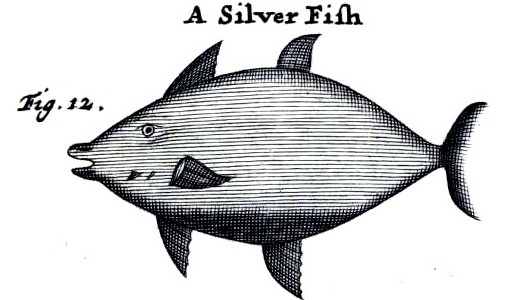

Silverfish

Image: William Funnell - Silver Fish, From A Voyage Round the World, opp. p. 18 (1707)

are noted by a variety of authors who visited Más a Tierra in the eighteenth century. Funnell, Cooke, Rogers and Anson all count them among the fish they caught to eat.30 Silverfish is a colloquial name; no other generic fish name found here encompasses quite as many diverse species as this term. (Wikipedia lists fish from 18 different families under as silverfish, although they are mostly similar in appearance.31)

Funnell, who was at the island in 1704 with Dampier, gives a detailed description of what he saw: "The Silver-fish here… having but six Fins, viz. four large ones, two upon his Back, and two opposite under his Belly; and one small one on each side near his gills. It hath a small Eye, and a great Bottle nose. It is a very flesh[y] Fish, and the Flesh is extraordinary white and good; they are commonly about twelve or thirteen inches long and about seven Inches deep; with a half-mooned tail"32. He even provides a sketch of the fish shown above left.

Photo: Dmitriy Konstantinov - Macroramphosus scolopax

Funnell's description is difficult to reconcile with the fish shown by Dyer and Westneat in their research, however. The only fish they picture which have a 'great bottlenose' are in the Macroramphosus family. Both the Macroramphosus scolopax (seen at right) and Macroramphosus gracilis which has slightly different coloring are commonly found around these islands in very deep waters. However, their fin configuration and shape are so unusual and their eye so large that they cannot be what Funnell is talking about.

None of the other fish Dyer and Westneat found there have a true bottlenose, so unless there was a fish commonly around the islands three hundred years ago which isn't there today, Funnell's description is not very helpful in identifying what this might be. Looking instead of the one of the types of Atlantic fish commonly identified as silverfish today suggests that the sailors could have been talking about Psuedocaranx chilensis.

Silverfish (Atlantic Tarpon) to Psuedocaranx chilensis Comparison |

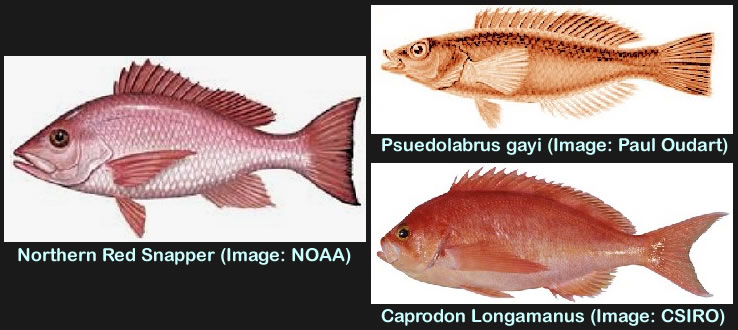

Cooke includes snappers in his list of fish caught about a mile away from Cumberland Bay.33 Dampier noted that snappers were plentiful in March of 168434, providing a description of these fish in his book. "It hath a large Head and Mouth, and great Gills. The back is of a bright red, the belly of a Silver Colour: The Scales are as broad as a Shilling. The Snapper is excellent Meat."35 He goes on to state that he has seen snappers only in the West Indies and the Pacific Ocean. A number of fish common to this area are red, although only a few have silver bellies. This might be either Psuedolabrus gayi or Caprodon longimanus.

Northern Red Snapper to Psuedolabrus gay and Caprodon Longamanus Comparison |

The last fish in this list are referred to as sea-wolves aka wolfish. It is included in lists of fish caught by both Jacob Le Maire in 1616 and Cooke in 1709.36 This is likely a reference to Scartichthys variolatus.

Wolffish to Scartichthys Variolatus Comparison |

1 James Burney, A Chronological History of the Voyages and Discoveries in the South Sea, Part III, 1813, p. 18; 2 Basil Ringrose, ‘Containing the dangers Voyage and bold Assaults of Captain Bartholomew Sharp’, Bucainers of America, 1684, p. 122; 3 Richard Walter, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 424; 4 Alan M. Friedlander, Enric Ballesteros, Jennifer E. Caselle, Carlos F. Gaymer, Alvaro T. Palma, Ignacio Petit, Eduardo Varas, Alex Muñoz Wilson, & Enric Sala, "Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots," PLoS ONE 11(1):e0145059, gathered 5/26/20; 5 Bryan Dyer and Mark W Westneat, "Taxonomy and biogeograph of the coast fishes of Juan Fernandez and Desventuradas islands, Chile", Revista de Biologia Marina y Oceanografia, Sept 2010, p. 590; 6 Friedlander, et. al., gathered 5/26/20; 7 Walter, p. 125; 8 "cod (n.)", etymonline.com, gathered 6/22/20; 9 "brême", en.wiktionary.org, gathered 6/22/20; 10 Glenn Gutkowski, "The History of Cod", onthewater.com, gathered 6/22/20; 11 Edward Cooke, Voyage to the South Seas, 1712, p. 146; 12 Jacob Le Maire, “Australian Navagations”, The East and West Indian Mirror, J.A.J. DeVilliers, ed., 1906, p. 190; 13 William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 21; 14 Cooke, p. 115; 15 George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 253; 16 Richard Simson, Observations Made During a South-Sea Voyage, 1689, Quoted in Jonathan Lamb, Vanessa Smith & Nicholas Thomas, Exploration and Exchange: a South Season Anthology, 1680-1900, 2000, p. 34; 17 Funnel, p. 21, Cooke, p. 115 & Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 131; 18,19 Shelvocke, p. 253; 20 Walter, p. 176; 21 Le Maire, p. 190 & Cooke, p. 115; 22 Rogers, p. 131 & Cooke, p. 115; 23 Shelvocke, p. 253; 24 Walter, p. 125; 25 Dyer and Westneat, p. 593; 26 William Dampier, A New Voyage Round the World, 1699, p. 89; 27 Rogers, p. 131 & Cooke, p. 115; 28 Dampier, p. 91; 29 Funnell, p. 21; 30 Funnell, p. 24, Cooke, p. 115, Rogers, p. 131 & Walter, p. 176; 30 "Silver-fish (fish)", wikipedia.com, gathered 6/25/20; 32 Funnell, p. 24; 33 Cooke, p. 114; 34 Dampier, p. 89; 35 Dampier, p. 91; 36 Cooke, p. 115