Bahamian Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Bahamas Page 1

"The pirates needed not only places to lurk and shelter, share out their plunder, and lick their wounds, to water, provision, and repair their ships. They needed something more substantial: a permissive shore-based community that would act as a kind of semipermeable membrane between them and the larger society and economy. Such townships as Nassau provided inns and quasi-brothels, stores of provisions, arms, and ships' supplies. But they were also places where cargoes and ships could be disposed of, or through which successful or satiated pirates could filter into a more respectable life." (Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 110)

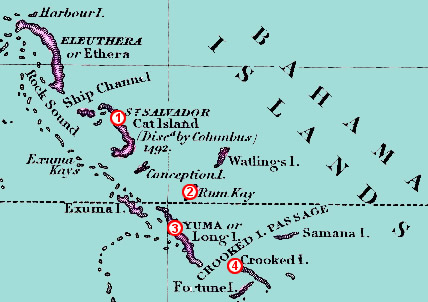

Cartographer: Samuel Augustus Mitchell - The Bahamas, From A Map of the West Indies (1849)

Unlike Jamaica and Barbados, which were English trading centers during the golden age of piracy, the Bahamas (called by the French the Lucayas) were really something of a backwater. "Their main significance at the time was geographic, as they were located across the Straits of Florida from Spanish-controlled territory. This provided them with an ideal location for preying on the western Atlantic shipping lanes. Outside of temporary periods of political instability associated with regional warfare, the Bahamas remained an unimportant peripheral colony."1

However, they were one of two locations which were regularly used by pirates to provision their ships during the golden age of piracy and much of their reason for inclusion here stems from this history. Golden age pirates may have preyed on many locations to recruit food and snuck into many others to either steal, trade for or purchase it, but those sailing in the Caribbean knew they could rely on the Bahamas to supply their needs over and over again. The reason for this was that there was little government in the Bahamas and the pirates could buy, sell and trade with unscrupulous suppliers living there and carouse with the proceeds, abusing the few unfortunate honest settlers on these islands. Such a situation was too good to last, however, and with the arrival of Woodes Rogers, the freewheeling Bahamian pirate lifestyle ceased.

Most of the sailor's accounts of victualling here come from the pirates along with a few unfortunate merchant ships who were driven there by storms or need, sometimes failing to successfully navigate the shallow waters around the nearly 700 islands, islets and cays. The history of Bahamian victualling is somewhat slight since most of the settlers were generally not very interested in planting or animal husbandry, although there is quite a bit of discussion about the potential of the islands for them. Unlike Jamaica and Barbados, there is only one detailed contemporary account of the flora and fauna available in the Bahama Islands, although it does provide a nice overview of what was eaten by the Bahamian residents.

1 Heather Hatch, Harbour Island - The Comparative Archeology of a Maritime Community, 2013, p. 3

Bahamian History Related to Food

Like Jamaica,

Taino Preparing Manioc and Corn, From La historia del mondo nuovo, By Girolamo Benzoni (1565)

the history of the Bahamas can be broadly divided into three parts. They were first inhabited by a group of Taino natives called the Lucayans who lived there for centuries before the first Europeans arrived. The second part of Bahamian history began with the arrival of the Spanish in the person of Columbus. He made landfall there on his first voyage, arriving on what was probably San Salvador Island in 1492. Not finding what he wanted , Columbus sailed to several islands, eventually making his way to Cuba. The Spanish had little use for the island, although they enslaved the Taino people, moving many of them to Cuba where they died of disease and ill usage. The third part of Bahamian history concerns the the first Europeans to try and settle the Bahamas. This began with a French settlement, which was soon abandoned, followed by a more lasting English settlement. They claimed ownership in 1629, sending settlers there in 1647. Because they were so remote, off the main sailing routes and sparsely populated, the Bahamas were not highly regarded during this time resulting in their not not being effectively governed. This created an opportunistic environment which was well-suited to the pirate lifestyle, a state in which the Bahamas continued until the arrival of Woodes Rogers in 1718.

The Lucayan Taino Natives in the Bahamas

One of the first-known natives of the Bahamas called themselves 'Lukku-cairi' (people of the islands), which the first Europeans understood as Lucayan1.

Carib Fishermen, From La historia del mondo nuovo, By Girolamo Benzoni (1565)

They were a branch of the Taino natives who populated other islands in the Caribbean, likely having made their way to the Bahamas some time in the first century A.D. (The exact date of their arrival isn't clear.) Little has been recorded about the Lucayan Taino people's lifestyle, so it is challenging to present a very clear picture of them in the Bahamas. Historical researcher Sandra Riley calls them "simple agricultural people"2 and it is likely that they either harvested what grew naturally in the islands or planted seeds in the rich ground of the hollows near shade trees in the valleys.3 Their tools were constructed of stone and bone and remnants of pottery made from clay and shells have been found, indicating how they hunted and ate. "Like many island cultures, the Lucayan people fished, grew crops and had a trading network with other islands."4 Historian Michael Craton suggests that their diet would have included the types of foods eaten by other Tainos including cassava, sweet potatoes, arrowroot, peanuts and beans, things they likely brought with them and cultivated.5 They may also have eaten papayas and pineapples, and enjoyed wild fruit such as guava, mammee apple, guineps, scarlet plums and tamarinds."6 Like the Europeans who followed them, they would likely have eaten iguana and land-crabs as well as fish caught with bone or shell hooks.

1 'First Settlers of the Bahamas', bahamasnet.com, gathered 5/20/20; 2 Sandra Riley, Homeward Bound - A History of the Bahama Islands to 1850, 2015, p. 8; 3 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 82; 4 Dennis Plunkett, 'Who Were the Lucayan Indians?', bahamastourcenter.com, gathered 5/20/20; 5 Michael Craton, A History of the Bahamas, 1986, p. 20; 6 'First Settlers of the Bahamas'

The Spaniards in the Bahamas

Bahama Islands Where Columbus Stopped On His First Voyage (October, 1492)

Cartographer: Samuel Augustus Mitchell - From A Map of the West Indies (1849)

The second part of Bahamian history occurred with its discovery by the Spanish. Christopher Columbus was the first European captain to make landfall in the Bahamas, sailing into Long Bay and most likely stopping at San Salvador Island (1) on October 12th, 1492. Columbus wrote of the Taino natives, "They... came to the ship's boats where we were, swimming and bringing us parrots, cotton threads in skeins, darts, and many other things; and we exchanged them for other things that we gave them, such as glass beads and small bells."1

From there, Columbus sailed at dawn on the 14th to what he called Santa Maria de la Concepcion, which is today called Rum Cay (2). Here, he said that the natives "brought us water, others came with food, and when they saw that I did not want to land, they got into the sea, and came swimming to us."2 On October 16th, Columbus sailed from there to Long Island (3) which he called Fernandina where the natives again brought them water, even filling their casks for them. He commented that it was "a very green island, level and very fertile, and I have no doubt that they sow and gather corn [Indian corn] all the year round, as well as other things."3

Fanciful Drawing of Columbus Landing and Trading with Lucayan Tainos (c. 1860)

Two days later, he sailed for Crooked Island (4), which Columbus enthused was the most beautiful he had seen. "The flocks of parrots concealed the sun; and the birds were so numerous, and of so many different kinds, that it was wonderful. There are trees of a thousand sorts, and all have their several fruits; and I feel the most unhappy man in the world not to know them, for I am well assured that they are all valuable."4 Beautiful it may have been, but they did not find any gold there, so they headed for Cuba after trading bells and beads withe the Lucayans for water. Nor was this beauty to attract the lasting attention of the Spaniards who followed Columbus; they found other Caribbean Islands to be better sources for food, water and other resources. "Although known to seafarers and traders, the Bahamas remained relatively unexplored and virtually uninhabited during the sixteenth century."5

The First European Settlements in the Bahamas

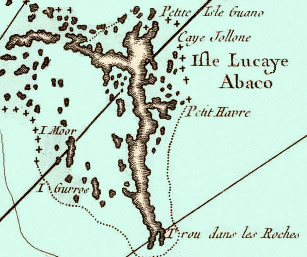

Cartographer: Jacques Nicolas Bellin - Abaco/Lucaye (11764)

The third part of the history of the Bahamas involved their actual settlement by Europeans. The first attempt at this was by the French, who tried to establish a community on Abaco - an island they called Lucayone - in 1565. (Seen at right. For it's location in the Bahamas, see A on the map in the section below.) Jacques-Nicholas Bellin said in his Description Geograpique that the settlers found Abaco "had good ports, safe harbours, a quantity of pigs and salt, and many sources of good water."6 The settlement did not last, if it ever began, however. A second ship sent from France to the settlement some time later found no trace of original settlers.7

Another French settlement was proposed when the Bahamas were granted to a Huguenot in 1633, but this settlement was never established due to restrictions on the type of settlers allowed by the grant.8 Such attempted French settlements were blips in the history of the Bahamas. Most of the written history of Bahamian colonies through the end of the golden age of piracy is that of the English, who wrote extensively about their occupation. Like the settlement of the Bahamas themselves, this can be broadly divided into three parts - Early English Settlements; War, Chaos and the Kernel of a Pirate Haven, and The Flying Gang Pirates and Their Downfall.

1 Steven Kreis, Journal of the First Voyage of Christopher Columbus, Document No. AJ-061, Wisconsin Historical Society, p. 111; 2 Kreis, p. 113; 3 Kreis, p. 119; 4 Kreis, p. 125; 5 Sandra Riley, Homeward Bound - A History of the Bahama Islands to 1850, 2015, p. 25; 6 Riley, p. 26; 7 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 65; 8 Heather Hatch, Harbour Island - The Comparative Archeology of a Maritime Community, 2013, p. 56

Early English Settlements

The Bahamas were claimed by England in an official grant to their Attorney General

Location of New Settlement Established Before 1668

Cartographer: Samuel Augustus Mitchell - From A Map of the West Indies (1849)

Robert Heath of the Province of Carolina, which included the Carolinas "together with the Islands of Veajus [probably Ponce de Leon's rocks on the Little Bahama Bank which included Abaco] and Bahamas [Grand Bahama], and all other islands lying southerly or near upon said continent."1 However, no one actually settled on the islands for almost two decades. The first exploration for English settlement came from a group of Bermudian dissidents who sailed in two ships to the Bahamas while looking for a good location for an independent colony. This venture was unsuccessful. Of the settlers, Bermuda Sheriff William Reynor wrote "one of those vessells, with sundrye pretious soules in her, never retorned; but without question [has been] loste. Thother sent, the last sommer, is retorned, but without discouerye of that Ilande we aimed at, And all throughe wilfull neglect of those imployed."2

English settlement of the Bahamas was to come through the efforts of former (and future) Bermuda governor William Sayle, who began promoting the idea of establishing such a settlement islands in 1646. Early in the next year, Sayle published A Broadside Advertising Eleuthera and the Bahama Islands, to promote this, a gambit embraced by 25 shareholders who formed the Company of Eleutheran Adventurers in July of that year. Sayle's design was to establish a community free from the English government and established religion.3 'Eleuthera' was a reference to the Greek word for freedom.4 Such a description has the glimmering of the sort of government which pirates would embrace.

Sayle, chosen governor of Eleuthera by the Adventurers, sailed for the Bahamas with about seventy other prospective settlers,

Preacher's Cave, Eleuthera, Bahamas

probably in his ship William accompanied by a small shallop in the Spring of 1648, carrying the necessary provisions and supplies.5 Their ship wrecked on their way to the island of Eleuthera (B), although all but one person made it to shore. However, "all their provisions and goods were lost, so as they were forced (for divers months) to lie in the open air, and to feed upon such fruits and wild creatures as the island afforded."6 Their precise landing point wasn't clear, but archeological evidence suggests it was on the northern part of the island and tradition holds that they first sheltered in Preacher's Cave.7

An act was passed in 1650 declaring Sayle's settlers as "the true and lawful Proprietors of all those Islands lying betwene the degrees of twenty fower and twenty nyne Northlatitude from the Equinoctiall and in longitude from Florida to the Sumers Islands"8. Sayle's intent was to establish another plantation community in the Bahamas, as suggested by one of his directives: "'To take care that two fifths of all the land respectively of equal goodness with what the people plant be reserved for the Lords Proprietors and such as they constitute the nobility.' This highlights two assumptions: first that people would be interested in planting, and second that the land was good for cultivation."9 However, this did not prove to be the case.

The community had trouble maintaining itself and a collection by people in Boston-based churches was taken up to support them. The churches raised £800 in an effort to purchase provisions which arrived in the Bahamas in June of 1650.10 Even with this money, many of the original settlers gave up and decided to return to Bermuda during the next six years. The community continued to struggle; even Sayle returned to Bermuda in March of 1657 aboard the ship John.11 Not everyone gave up on the settlement, however. The remaining "colonists increasingly settled on the neighboring smaller islands, both for security from foreign attacks and for better access to the sea using the mainland [Eleuthera] mostly for woodcutting, growing provisions, and running hogs."12

Although he had left, Sayle was still interested in the Bahamian settlement. From Bermuda, he sailed to London in 1658, obtaining backing for a trading voyage which would benefit the remaining settlers. Around this time, his son Thomas became captain of the William which carryed passengers and goods from London to Bermuda. On one of his voyages, a storm forced him to shelter in the harbor on an island that was to become the future capital of the Bahamas.13 It had been settled by a group fishermen and wreckers in 1666 who referred to it as Sayle's Island in reference to it being a shelter for Thomas Sayle, although they eventually renamed it New Providence in reference to the Puritan-privateering colony of Old Providence off Nicaragua (C).14

During the English Civil War, Robert Heath lost his rights to the Province of Carolina (which included the Bahamas) because he supported the King. Upon his assumption of power, Charles II bestowed the Carolina charter to eight men called the Lords Proprietors in 1663. In July of 1668, six of these eight Carolina

The Charter of Carolina by Charles II to the Lords Proprietors (1663)

Cartographer: Samuel Augustus Mitchell - From A Map of the West Indies (1849)

Proprietors were specifically granted rights to the Bahamas. "The patent included the rights to whales, sturgeons, and all other ‘royal fishes’ in the sea, bays, inlets, and rivers. Powers were extended to the Proprietors to make grants of land, levy customs' fees and appoint governours."15

John Dorrell and Hugh Wentworth wrote to proprietor Ashley Anthony Cooper in February of 1670 that New Providence contained about 300 people. "The island is very healthy and has gallant harbours, it produces as good cotton as is ever grown in America, and gallant tobacco. Their great wants are small arms and ammunition, a godly minister, and a good smith."16 They also requested the establishment a government. Since nothing was said about a need for food, they must have found the island residents to be effectively supplied by what could be harvested and the provisions from incoming ships.

On August 23, 1672, New Providence governor John Wentworth wrote Jamaican governor Thomas Lynch that "all growths [are] suitable for these climes, and all creatures thrive well, the salubrity of the air beyond all places he is acquainted with; plentifully accommodated with fresh water and fish, and ordinarily with timber; a harbour for ships drawing 15 foot water"17. However, Lynch received a petition from the settlers during this time which warned that "their known incapacities are so great, and their lives and fortunes are so unsafe and perilous" because of threats from the Spanish and French.18 Lynch's view of the potential of the Bahamas was not as positive; he wrote to the Lords of Trade and Plantations in June of 1682 that the islands "are barren and good for little, frequented by only a few straggling people who receive such as come to dive for silver in a galleon wrecked on that coast."19 In another letter, this one to Bahamian Governor Robert Clarke, Lynch complained "that your Islands are peopled by men who are intent rather on pillaging Spanish wrecks than planting"20, suggesting that little effort had been made by the residents to grow crops in the Bahamas.

John Oldmixon wrote in 1708, New Providence "had little or none [of the needed provisions],

Artist: Andreas Achenbach, Wreckers in Port (1855)

but what came from Carolina; however, the Traders here kept Store Houses, to supply, those that wanted, and they were a great Relief to the unfortunate [shipwrecked] Mariners, of whom we are speaking."21 Oldmixon goes on to state that, in return for their help, the people of Providence, Harbor Island and Eleuthera made prizes of the 'unfortunate Mariners' wrecks. Wrecking was a continuous thread through the history of the Bahamas up to and including the golden age of piracy.

Oldmixon characterized many of the settlers who arrived in the islands in 1672 as 'lewd' and 'licentious'. By way of example, he said that the residents, not liking rules laid down by Governor Charles Chillingsworth (1676-7), they "shipt him off for Jamaica, and liv'd ev'ry Man as he thought best for his Pleasure and Interest."22 The people were fiercely independent and would not stand for strict governance. Sandra Riley explains, "Prior to the arrival of Woodes Rogers in 1717, the proprietary governours proved by and large an unsavory lot of tyrants, despots, drunkards, thieves, and cowards. The few who tried to maintain a modicum of order were met with resistance and either abandoned their posts or were driven off the island by the inhabitants."23

Spanish Attack on Shore (1745)

Of course, this independent community still had external threats. On January 19th, 1684 the Spanish, never completely happy with having their former possessions taken from them by the English, attacked New Providence. It was suggested that the number of settlers at that time were about four hundred men and two hundred women.24 The Spaniards pillaged the town, taking everything of value and putting it on the largest ship in the New Providence harbor. They then sailed to Eleuthera and destroyed the town there. Returning to New Providence, they burnt the city and carryed off some of the people and enslaved them.25 Oldmixon says that the Spanish "destroy'd all their Stock, which they could not, or would not carry off, and took the Governour away with them in Chains, having burnt the few Cottages that were upon the Place. The Inhabitants deserted it after this, and remov'd to other Colonies."26 While a damaging blow, it was not the end of the Bahamian colony. A small group returned under the leadership of preacher Thomas Bridges in 1686, although it must have been a hardscrabble existence since many of the former inhabitants had left. The first real boost for the Bahamian populace after the Spanish attack occurred they next year when the Spanish galleon Concepcion wrecked off the coast of Hispaniola and people flocked to the islands to salvage the ship. Most of the resulting treasure didn't remain in the the Bahamas, however. This allowed those who had settled there to resume their old lifestyle.27

1 Sandra Riley, Homeward Bound - A History of the Bahama Islands to 1850, 2015, p. 26; 2 The Massachusetts Historical Society, Winthrop Papers, Vol. V, 1645-1649, 1947, p. 73; 3 Craton and Saunders, p. 74; 4 Jane S. Day, Preacher's Cave: Developing A National Heritage Tourism Site In Eleuthera, Bahamas, Doctoral Dissertation, 2010, p. 56-7; 5 Craton and Saunders, p. 76-7; 6 Riley, p. 29; 7 Craton and Saunders, p. 77 & Heather Hatch, Harbour Island - The Comparative Archeology of a Maritime Community, 2013, p. 57; 8 Riley, p. 31; 9 Heather Hatch, Harbour Island - The Comparative Archeology of a Maritime Community, 2013, p. 60; 10 Riley, p. 31; 11 Riley, p. 32; 12 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 79; 13 Riley, p. 33; 14 Craton and Saunders, p. 79; 15 Riley, p. 37; 16 Calendar of State Papers Colonial (CSPC), Vol. 7, 1669-1674, Item 53; 17 CSPC, Vol 7, Item 916; 18 CSPC, Vol 7, Item 916.i.; 19 CSPC, Vol 11, 1681-1685, Item 552; 19 CSPC, Vol 11, Item 668.i; 21 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 349; 22 Oldmixon, p. 350; 23 Riley, p. 40; 24 Craton and Saunders, p. 87; 25 Craton and Saunders, p. 98-9; 26 Craton and Saunders, p. 99-100; 27 Craton and Saunders, p. 100