Bahamian Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Bahamas Page 2

Bahamian History Related to Food, Continued

War, Chaos and the Kernel of a Pirate Haven

The distaste for official oversight and cavalier attitude towards laws among many of the Bahamian residents combined with their shallow drafts close to the triangle trade routes made the Bahamas an ideal location for war privateers. However, little is written about how those who remained on the islands during this period procured food.

A Caribbean Privateer (18th Century)

While food could be grown in select places on the islands, the residents up this time seem to have been more interested in higher profit activities such as whaling, wrecking and smuggling. Much of the food consumed was apparently imported for the use of the residents and distressed ships from the colonies.

The War of the League of Augsburg began in 1688, pitting England and Spain against France until its end in 1697. The Bahamas became a good location for privateers to use as their base. "Some new settlers and many transients flocked to New Providence, which at least temporarily took on the air of a true colonial center."1 Appropriate to the new residents, Cadwallader Jones was appointed governor of the islands by the Lord Proprietors in 1690. Of Jones, Oldmixon says, "He pardon'd Capital Offenders, seiz'd the publick Treasure, wasted and converted it to his own use. He neglected the Defence of the Island, imbezel'd the Stores of Powder, converted the Lords Proprietaries Royalties to his own use, invited Pyrates to come to the Port."2 A comment from this period implies that food was grown on the islands for consumption up until they had a bad season. Barbadian Edward Richier wrote in April 12,1692 that following a failed crop and lack of government funds, "Many of the inhabitants are leaving to find provisions elsewhere. Eighty left for the Bahamas ten days ago."3

Captured by a Rabble, From History of England for the Young, By Robert Tyrrell (1856)

Jones gave these people commissions against the recommendation of his council, technically making them legal privateers. Their behavior presaged that of the 'Flying Gang' pirates twenty five years later. Merchant and Deputy Secretary Thomas Bulkley later said that Jones was "guilty of arbitrary and tyrannical exercise of power, of neglect to fortify the place, of malversation of the public funds, and of inviting a notorious company of pirates to make war upon your subjects"4. Jones attempted to prosecute him but, as Bulkley explained, "some desperate Rogues, Pyrates, and others, gather'd together an ignorant seditious Rabble, who on the 27th of February, 1692, with Force of Arms rescu'd the Governour, proclaim'd and restor'd him to the Exercise of his Despotick Power."5 The same people took Bulkley from his house, "shut him up in a Close dark Confinement, threaten’d him with the Torture, and forc'd him to deliver all the Books having any relation to his Office of Deputy-Secretary."6 He remained in jail for 485 days, with one account noting that "his House, &c. therein, hath sundry times been Broke open in a Felonious manner, by Armed Pirates... [which] were the cause of Convulsion Fits, Painful Languishing Sickness, and finally of Death, to the said Bulkleys Wife."7 He was released by subsequent governor Nicholas Trott in April of 1694. Upon his release, Bulkley wrote the Lords Proprietors and again accused Jones of high treason, although he said Trott delayed his attempt allowing Jones to escape.8 Bulkley's complaint was sent from person to person for months, never resulting in prosecution.9

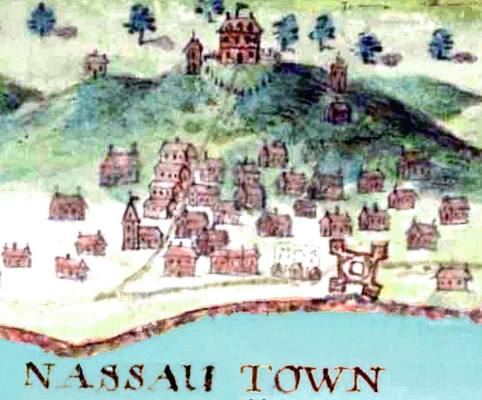

Nassau Town & Fort, From Exact Draught of the Island of New Providence (1st Half of 18th c.)

Nicholas Trott was did much to build the town of Nassau during his tenure between 1694 and 1697. He gave the town its' new name (in honor of William III of the Orange-Nassau House), formally laying out the town and building the first fort for protection of the harbor.10 John Oldmixon (who knew Trott personally11) heaped praise on the governor for the fort. He noted that it had 28 Cannon and demi-culvers, and "was such a Security, in his time to the Island, that tho the French landed several times, they could make nothing of their Descent."12 However, the Lords Proprietors took issue with the way he planned to do it, explaining "it seems so worded that our consent may do

injustice to many owners of land, who would thereby be deprived

of their inheritance, and to ourselves by giving away our quit-rents [rents paid in lieu of services required by the land-owners]"13.

Some of Trott's more questionable activities as governor of the Bahamas found their way into the official records years after he was removed from office.

Survivors During a Storm (18th Century)

A Dutch ship, the Juffrow Geertruijd, was wrecked in the Bahamas in March of 1695. The crew made their way to New Providence where Trott took their arms, allegedly refusing to return them unless they paid him 12 pieces of eight for each weapon. The Bahamians raided their wrecked ship, taking 33,000 pieces of eight from her and sharing it amongst Trott's confederates. The crew asked to leave the islands, explaining that they had "little money and provisions, [telling] him they were honest men and no pirates, but Trott refused to let them go until they had paid him 40 pieces of eight per man and 20 per boy."14

Trott's answer to these charges was that the Dutch said they "had lost their ship by stress of weather about 50 leagues from that place, and wanted provisions and all necessaries, he permitted them to come on shore." He said they gave him their weapons as a sign of their peaceful intentions and didn't return them because "they were mutinous fellows of divers nations and would be apt enough to attempt some mischief"16. He further stated that the sailors made him give them the money they had gathered upon leaving their ship and had only received small gifts from them for his trouble. William Thornburgh, acting on behalf of Lords Proprietor John Colleton, sent Trott's response to Board of Trade Secretary William Popple, adding that the letter was "so foolish and extravagant.... that he hopes they will obtain no credit, as he avers they deserve none."17 The Trade Council accordingly pointed out several inconsistencies and a lack of proof in Trott's reply to the King, recommending that he be prosecuted in this matter.18

The acceptance of pirates and privateers in the Bahamas under Trott was notable. Colonial administrator Edward Randolph wrote that they had long been a refuge of pirates, providing an example: "In 1693 the master of a Barbados ship, richly laden from Jamaica to London, ran his ship wilfully aground in the Islands, and he and his sailors divided the money and cargo. The Governor had his advantage from it."19 In 1695, Thomas Laurence, the Secretary of Maryland explained of pirates and privateers, "They come first to Providence and the Bahama Islands and [then] to South Carolina, where they leave or dispose of their ships, and from thence disperse into these parts in small vessels."20

Even the somewhat sympathetic Oldmixon couldn't overlook the most significant black mark on Trott's governorship. Pirate Henry Every landed on New Providence in February of 1697 after ransacking the Grand Mughal's vessel in the Indian Ocean, claiming to be merchant sailor Henry Bridgeman. He was able to purchase and provision a new ship and disperse his treasure and men. Oldmixon says that Trott told him there were only 70 Bahamians able to protect the island while Every had 100 pirates, so he had little choice. However, he goes on to (perhaps wryly) note that "‘Twas very unfortunate, that there should be only 70 Men upon the Island at that time, when a little before and a little after, there were 200

Pirate Henry Every and the Capture of the Gang-i-Sawai (c. 1702)

Men, which was the greatest Number that could ever be muster'd in the Bahama Islands"21. (At the time of his trial over the matter in October of 1697, Trott said there were "113 of them besides negroes, and there were not above 60 men in Providence at the time."22) He also suggests that based on "the Character we have had of the People of Providence, we cannot think that Pyrate, who was very rich, was unwelcome to them."23

It generally understood that Trott recognized Every. John Graves wrote the Council of Trade and Plantations in May, 1698 that "The late Governor Trott got considerable out of them (sic); particulars I cannot certify, but it is reported at least £7,000. This Governor has fleeced those he found here and gives them another instrument of writing for a pardon."24 At Trott's trial, he was said to have accepted £1000 to allow the pirates to land, which he denied. Trott's complicity with the pirates was never fully proven, although he was removed from his governorship. One of the explanations offered was that although Trott may have suspected Bridgeman/Every was a pirate, he may also have just been an interloper - a ship violating the Royal African Company's trade monopoly. Asked why an interloper would stop in the Bahamas, Trott's legal representatives replied, "he was short of provisions and unsound owing to the worm."25

The Lords Proprietors sent Nicholas Webb to replace Trott in February of 1697, charging him with looking into Trott's case. Webb's response to them supported Trott's version of the events.26 Governor Webb proved to be little better than his predecessors. Edward Randolph reported in April of 1698 that "Captain Webb seizes and clears vessels, making the masters pay

Nassau Harbor as Seen From Hog Island, From Promotional Material by

the New York, Nassau and West India Mail Steamship Line (1877)

what he pleases, taking no notice of Mr. [John] Graves, the King's Collector of Customs."27 He appointed several former Madagascar pirates as governors of other Bahama Islands and members of his own government.28 Webb himself said that it would be impossible to suppress piracy so long as various colonial governments and the Bahamas remained independent of the Crown. "The owners of these tracts of land [the Lords Proprietors], ...do not allow their Governors enough to support them honourably in their stations, which puts them upon indirect means to get a better maintenance. Besides, they generally appoint persons of slender fortunes with an indifferent stock of honesty"29

Webb eventually got into trouble with the Lords Proprietors for commissioning five warships to pursue pirate James Kelly in 1699 under the command of Read Elding. Elding instead captured a Boston-based merchant ship and brought her back to Nassau, apparently sharing the loot with Webb. In response, the Lords Proprietors told the Bahamian government they were appointing a judge to hear all such cases.30 Webb fled the Bahamas arriving in Newcastle, Pennsylvania in June, but got his comeuppance when pirates took the ship he was on along with all of his belongings.31

Read Elding assumed the governorship upon Webb's departure in April of 1699, even thought it was his fleet's act of piracy which was at the center of Governor Webb's controversy. He remained acting governor of the Bahamas until the June 27 of the next year.32 Despite his history,

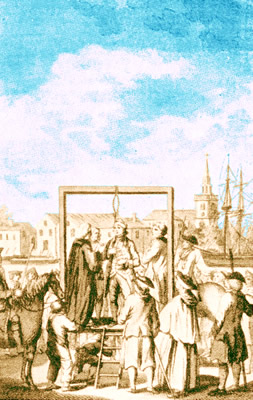

Artist: Robert Dodd

A Pirate Hanged at Execution Dock (c. 1795)

Elding appeared to seize upon the idea of capturing and punishing other pirates. He wrote James Vernon in October, "I have taken all possible care to see all His Majesty's laws put in execution. The West Indies are full of pirates. I have been so severe to those sort of people that about a fortnight now past I had a notorious pirate tried here, condemned and hanged."33

Not everyone was impressed with Eldings' new zeal in prosecuting pirates. Administrator Edward Randolph arrived on New Providence in March of 1700 and reported that Elding "supports himself in the lawfulness of the other commission [given to him illegally by Webb] to take pirates, but sets a very high value upon his services by the accidental seizing Hind the pirate [Hendrick Van Hoven] and afterwards executing six of his accomplices."34 (These men included Ounca Guicas, Frederic Phillips and John Floyd.35) Randolph further recommended that Elding be brought up on charges of piracy for taking the Boston-based merchant ship with his fleet of five ships the year before and resident Thomas Walker be made Governor.36

Thomas Walker stated in April of 1701 that Elding appointed pirates to oversee the prize court including one of Henry Every's former crewmen as Deputy Governor. Elding had done this because he was upset with the judge who had been appointed for the Bahamas by the Lords Proprietors for trying to collect the crown's 10% of all money retrieved from wrecks.37 Eldings' new appointees condemned four legal wood-harvesting sloops, the profits from which went to Elding and his cronies. Walker also was "credibly informed that the Deputy Governor has privately supplied known pirates about those Islands with liquors and refreshment, and underhand hath taken their ill gotten money for the same and enriched himself thereby."38 During Elding's tenure as governor, a French ship had run aground without damaging the ship, but the Bahamian wreckers sent their sloops out and plundered the vessel anyhow. The Bahamians said they gave "the ship's men a small boat with some provisions, and sends them back to [Hi]Spaniola againe, as the Sloop-Master and some others reported"39.

In July of 1701 newly appointed Bahamian governor Elias Haskett arrived after being appointed by the Lords Proprietors to replace acting governor Elding. He made Elding his deputy governor. Haskett was doubtful of the islander's claims that the French ship's men had been left new Providence in a

Artist: After Robert Deighton

A Fleet of Transports Under Convoy (1781)

small boat, so he sent a ship out to investigate the site of the shipwreck. There, his investigators found five dead men within a few miles of the wreck. He surmised that they had been killed for the cargo.

Haskett arrested Elding on charges of committing piracy and dealing with pirates, appointing Thomas Walker the Deputy Governor in his place. Haskett eventually decided to let Elding out on bail on the promise of good behavior. Conspiring with Ellis Lightwood (another man who was to be brought up on charges in the matter), Elding visited Haskett on the pretence of arguing against the charges against him. A body of his armed supporters followed him and subsequently took Haskett prisoner, wounding him several times in the process, and placing him in Fort Nassau in shackles. They also jailed two judges and the secretary, people who were in charge of overseeing Elding's trial as well making sure the crown got its ten percent of the money retrieved from them. The populace then voted Lightwood in as acting governor.40

Walker snuck an account of what happened into a hollowed out apple which he gave to William Davie, master of a ship which which was allowed to leave the island - the James City.42 Walker was soon arrested by the usurpers. In December, former governor Haskett wrote to the Council of Trade and Plantations of what happened, noting that Lightwood and Elding put him aboard a Ketch bound for New York where he said he was "most barbarously treated by [John] Graves, who did contrive severall times to murder me, but it pleased God to prevent him; He hath sworn to be true to the Rabble, for which he is sufficiently paid out of the plunder which was considerable"42. The plunder included most of Haskett's estate although he said he smuggled a small amount of money out by tying it around his waist. Graves was arrested in New York in late 1701 based on Haskett's complaint and eventually put in prison.43 Several complaints about the arrest were made and Graves was eventually released from prison in 1703.

When the War of Spanish Succession began in 1701, the Bahamas became a base for privateers seeking French and Spanish merchant ships. Unlike the buccaneers in Jamaica, these men did not successfully protect the islands, something blamed on the long-standing lack of support for defense of the islands. "[T]he failure of the Proprietors or Crown to provide adequate defenses left Nassau helpless before joint French and Spanish attacks, which in 1703, 1704 and 1706 so devastated the colony that all semblance of law and order disappeared."45 The enemy sailed against the Bahamas from Haiti in July of 1703 and took Nassau, destroying the fort, burning most of the town and capturing the governor.46 Nicholas Trott reported, "After the destruction of the settlement in 1704, all the inhabitants, except about 60 of the

Location of Bahamian Residents in Graves' 1704 Survey

Cartographer: Samuel Augustus Mitchell - From A Map of the West Indies (1849)

poorest were forced to desert the place."47 In 1709, the French and Spanish attackers "possessed themselves of several of the Bahama Islands and committed great cruelties on Her Majesty's subjects."48 During these attacks, the enemy took all the cannon on the island and by September of 1710, "[t]he side of the Fort next the sea having been demolished by the French and Spaniards, it will want reparation"49. The Council of Trade and Plantations further reported that of approximately 150 families formerly on New Providence, only 12 remained. The Council suggested that the queen send more cannon and enough provisions to supply the residents for a year.

The Bahamians nevertheless survived these attack. John Graves arrived in the Bahamas with incoming Governor Edward Birch in September of 1703. Graves surveyed the Bahama Islands in June of the next year, reporting that there were about 90 people living on Exuma Islands (D), 120 people on Cat Island (E), 160 on Eleuthera (F) and 60 on Harbor Island (G) and roughly 400 people on Providence (H). Of the outer islands, Graves said "in a little time they will be worse than the Wild Indians, and at the best they are very ready to succour and trade with Pirates; they have 12 or 14 small sloopes amongst them, that escaped the enemy, so that unless H.M. give immediate protection, it will become a second Madagascar [a recent pirate haven]."50 It is not clear from this how the islands would 'succour' the pirates, although those people who cultivated food in the Bahamas seem to have emigrated to Eleuthera and Harbor Island as we shall see.

Graves' concern was soon to become fact. In January, 1706, the Council of Trade and Plantations wrote the Queen:

From The Pirates Own Book, By Charles Ellms, (1837)

These Colonies are the refuge and retreat of Pyrates and illegal traders, and the receptacle of goods imported thither from foreign parts contrary to Law, in return of which commodities, those of the growth of these Colonies are, likewise contrary to Law, exported to foreign parts; all which is much encouraged by their not admitting Appeals. They give protection to deserters and malefactors… They do not in general take due care for their own defence and security against an enemy either in building forts or in providing their inhabitants with sufficient arms and ammunition against an attack, which is every day more and more to be apprehended, considering how the French power increases in those parts; nor have some of them any regular Militia established amongst them. These mischiefs chiefly arise from the ill use they make of the powers intrusted to them by their Charters, and the independency which they pretend to, presuming that each Government is obliged only to defend itself, without any consideration had of their neighbours, or of the general preservation of the whole51

Graves went to some lengths to try and convince the Crown to take charge of the Bahamas from the Lords Proprietors. He sent a letter to the Lords outlining his reasons that the islands needed to be defended. When that didn't receive any action, he published his letter in 1708, addressing it to the Houses of Parliament in England. Among other comments about the need for defense during the current war, he explained that even two small pirate ships could plunder the inhabitants of the Bahamas. Worse, "one small Pyrate, with Fifty Men that are acquainted with the Inhabitants (which too many of them are) shall and will Ruin that Place, and be assisted by the loose Inhabitants; who hitherto have never been Prosecuted to effect, for Aiding, Abetting

Artists: Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Pugin

A Meeting of the Board of Trade, From Microcosm of London (c. 1808)

and Assisting the said Villains with Provision, &c. nor is it in any Man's Power how to do it, without being furnish'd with Strength sufficient to put the Laws in Execution."52 This also failed to bring action.

In fairness to the Proprietors, they felt that the profits of the community from their land rents should pay for the defenses. In fact, as far back as October, 1691, they had directed Cadwallader Jones to "apply all our perquisites to the fortification of the Islands."53 Of course, Jones only enriched himself with any profits the island might generate.

On January 28th, 1709, Graves and John Ireland, a twenty-six year resident of the island, represented a petition of the merchants of the Bahamas to the Board of Trade and Plantations, noting that the Lords had sent almost no defensive supplies to the settlers. Graves said "that he had lived in the said islands (on and off) for about 22 years, and that in all that time the proprietors had never sent but four barrils of powder, that he had himself apply'd several times to the said proprietors for stores of war, and other assistance, which sometimes they promised to give, but however nothing was sent"54. The lawyer representing the merchants pointed out that the French and Spanish had ravaged the island several times without the Proprietors doing anything and "he hoped they would be of opinion that her Majesty do take the said islands under her imediate protection and government."55 Once again, no action was taken. By 1710, the government appeared ready to make the Bahamas a royal province and they asked Graves about the state of the islands. "Mr. Graves either was tired of the bureaucracy or simply had no more to add to his eight page memorial delivered to the Lords Proprietors of the Bahamas Island"56.

1 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 100; 2 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 351; 3 Calendar of State Papers Colonial (CSPC), Vol. 13, 1686-1692, Item 2170; 4 CSPC, Vol. 15, May, 1696 - Oct, 1697, Item 651; 5,6 Oldmixon, p. 354; 7 Thomas Bulkley, The Case of Thomas Bulkley, late of New Providence, merchant briefly represented to the Right Honourable the Lords of His Majesties Councel of Trade; 8 Thomas Bulkley, To the Right Honourable William, Earl of Craven, et al., 1694, pp. 1-6, Oldmixon, p. 355 & CSPC, Vol. 15, Item 651; 9 See CSPC, Vol. 15, Items 681, 695, 725, 729, 770, 787, 800, 814, 843, 845, 874, 877, 884, 923, 925, 952 & 1400; 10 Craton and Saunders, p. 101; 11 Pat Rogers, "An Early Colonial Historian: John Oldmixon and 'The British Empire in America'", Journal of American Studies, Aug., 1973, p. 121; 12 Oldmixon, p. 357; 13 CSPC, Vol. 14, January, 1694 - May, 1696, Item 1774; 14 CSPC, Vol. 17, 1699, Item 294.i; 15, 16, 17 CSPC, Vol. 17, Item 369.i; 18 CSPC, Vol. 17, Item 575; 19 CSPC, Vol. 15, Item 149.i; 20 CSPC, Vol. 14, Item 1916; 21 Oldmixon, p. 356-7; 22 CSPC, Vol. 16, 1697-1698, Item 928; 23 Oldmixon, p. 356; 24 CSPC, Vol. 16, Item 444; 25 CSPC, Vol. 16, Item 928; 26 CSPC, Vol. 16, Items 710 & 928; 27 CSPC, Vol. 16, Item 404; 28 CSPC, Vol. 19, 1701, Item 180; 29 CSPC, Vol. 16, Item 451; 30 CSPC, Vol. 17, Items 464 & 465; 31 CSPC, Vol. 17, Items 550; 32 CSPC, Vol. 18, 1700, Item 597; 33 CSPC, Vol. 17, Item 840; 34 CSPC, Vol. 18, Item 250; 35 Sandra Riley, Homeward Bound - A History of the Bahama Islands to 1850, 2015, p. 50; 36 CSPC, Vol. 18, Item 250; 37, 38 CSPC, Vol. 19, Item 1042.ix(a); 39 CSPC, Vol. 19, 1701, Item 655; 40 CSPC, Vol. 19, Item 1042.viii.c; 41 CSPC, Vol. 19, Item 1042.viii.d; 42 CSPC, Vol. 19, Item 1113; 43 CSPC, Vol. 20, 1702-1703, Items 340.iii & 340.v; 44 See CSPC, Vol. 20, Items 295, 324, 336, 340.iii, 383, 444, 534 & 554; 45 Craton and Saunders, p. 103; 46 Oldmixon, p. 359-60; 47 CSPC, Vol. 33, 1722- 1723, Item 122; 48 Riley, p. 53; 49 CSPC, Vol. 25, 1710 - 1711, Item 405; 50 CSPC, Vol. 23, Item 277; 51 CSPC, Vol. 23, Item 18; 52 John Graves, A Memorial or a Short account of the Bahama-Islands, 1708, p. 7; 53 CSPC, Vol. 13, Item 1850; 54,55 Journals of the Board of Trade and Plantations, Volume 1, April 1704 - January 1709, p. 583; 56 Riley, p. 53