Bahamian Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 <<First

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Bahamas Page 5

Bahamian Food Descriptions

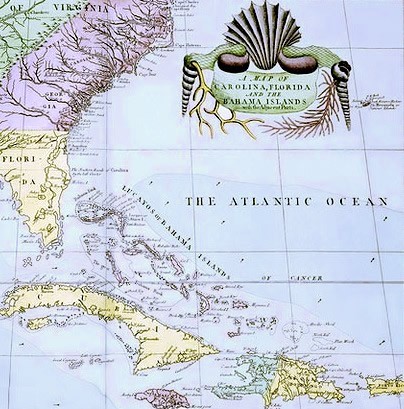

Map, From The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands,

By Marc Catesby (1754) Descriptions of the foods grown in the Bahamas are more limited than what was found for Jamaica and Barbados, perhaps in part because the growth of food was of secondary importance to most of the inhabitants of the islands. As the accounts previously cited suggest most Bahamian residents seemed interested in growing only what they required to live there, if they bothered to grow anything at all.

However, English naturalist Marc Catesby was invited to New Providence by Governor George Phenney around 1722 or 1723 resulting in his visiting New Providence, Eleuthera, Andros, Great Abaco and other islands nearby.1 During his time spent in the Bahamas, he made a variety of observations about the flora and fauna he found which he collected in two volumes called The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands. These books contained detailed color plates of the plants and animals he had seen. His images and comments make up the bulk of the information in this section. Other information about what grew in the Bahamas comes from various reports of the government concerning about the status of the islands.

1 Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol. 1, 1754, p. v

Fruit

Fruit seems to have been readily available in the Bahamas based on the attention it received in the period records. Before the rebellion turned him out in October of 1701, Bahamian governor Elias Haskett's description of New Providence stated that the island produced "oranges, lemons, pines [pineapples] and grapes in abundance, pumgranetts and several other sorts of fruit, which are common in the West Indies."1 Writing twenty-three years later, Governor George Phenney said that the Bahamas "naturally produce… oranges, citrons, lemmons, limas and salt in great quantitys."2 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders

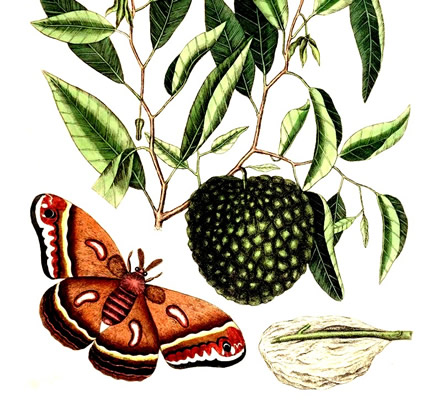

Sugar Apple (Annona squamosa) and Moth, From The natural history of Carolina,

Florida, and the Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754) suggest that while fruit found on the island were used by the inhabitants during this period, "but neither they nor imported fruit trees were cultivated until later years; even the easily grown indigenous pineapple was regarded as a dispensable luxury. …For over a hundred years, Bahamian agriculture was strictly for subsistence, regarded as a necessary evil; backbreaking and scorching work with frequent disappointments."3 The history of provisioning section bears this out.

Marc Catesby highlights a couple of the fruits found in the Bahamas. Among them are two apples - the seven years apple (Genipa clusiifolia) and the sugar apple or sweetsop (Annona Squamosa). He describes the seven years apple as "being shaded with green, red and yellow. When ripe, it is of the consistence of a mellow pear, containing a pulpy matter, in colour, substance and taste not unlike the Cassia fistula."4 He says that the sugar apple "is of a roundish conic form, covered with angular protuberances, within which is a sweet insipid pulp, with several shining black feeds lodged therein."5 He doesn't seem particularly impressed with the sugar apple, stating that although some people ate it, it was mostly left for the iguanas and other Bahamian wildlife.

Catesby mentions several other fruits, although his focus is clearly on the more

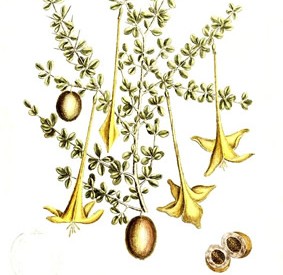

Lily thorn, From The natural history of Carolina,

Florida,

and the Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754)

exotic plants because he doesn't discuss any of the fruits mentioned by the two governors. He says four of these fruits are worth eating, although he adds that two of them are primarily left by the inhabitants for the wild animals in the Bahamas like the sweetsop. The first is the sapodilla (Manilkara zapota), which he says contains "a spongy pulp, full of juice, of a pleasant sweetness when the fruit is perfectly ripe; but if not, very astringent and disagreeable."6 The second fruit he discusses is the pigeon plum (Coccoloba diversifolia), which are purple and grow in bunches. "In December the fruit is ripe, and is the food of Pigeons, and many wild animals; it is a pleasant tasted fruit; the wood is hard and durable."7 The third fruit he felt was worth eating was the mangrove grape-tree (Coccoloba uvifera) which he thought had "a refreshing agreeable taste, and is esteemed very wholesome; but if the stone be kept long in the mouth, it is violently astringent: I never saw any but what grew near the sea."8 The last fruit he discusses is the lily thorn (Catesbea spinosa) which was eventually named for Catesby. He explains that it "has an agreeable tartness and good flavour, and seems as if it was capable of being improved by cultivation."9 Perhaps having this in mind, Catesby brought seeds of plants he found in the Caribbean back to England where some of his friends were able to raise them.

1 Calendar of State Papers Colonial (CSPC), Vol. 19, 1701, Item 655; 2 CSPC, vol. 34, 1724, - 1725. Item 424.ii; 3 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 82; 4 Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol. 1, 1754, p. 59; 5 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 86; 6,7 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 87; 8 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 96; 9 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 100

Vegetables and Bread

The period authors don't provides a nice an overview for the vegetables which grew in the Bahamas, although they do mention several of them.

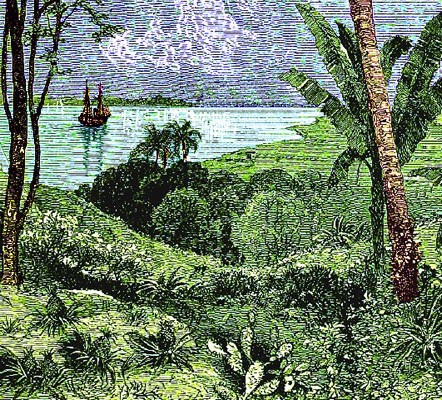

Hog Island View of Nassau Harbor, Bahamas. From New York, Nassau and West India

Mail

Steamship Line Promotional Material (1877) Governor Elias Haskett (1700-1701) rather unhelpfully says "here are several plantations now planted with ...all other roots that are common in America."1 'Roots', as noted previously, generally referred to a number of root vegetables din these descriptions. Marc Catesby is a little more illuminating, explaining that corn grew well in the 'white ground' (probably sand) which "produces a small kind of maiz, with good increase"2. Where 'rocks' (probably clods of dirt) could be broken apart, they were "piled in heaps, between which is planted yams, cassadar, potatoes, mellons, &c. which fructify beyond imagination."3 Historians Michael Craton and Gail Saunders mention other European vegetables grown in the Bahamas like onions and those introduced to the Caribbean by the Spanish and Portuguese such as guinea corn, blackeyed peas, yams and potatoes.4 Whatever else could be said about the growth of vegetables, it was quick; "Pease came up in 6 Weeks time, and Indian Corn in 12."5

As with other Caribbean locations, finding a substitute for wheat bread was a challenge for many Europeans. Catesby mentions the use of corn to make bread in addition to some European wheat. "[T]he first they cultivate, but not sufficient for their consumption. Wheat is imported to them in flower from the Northern colonies. There are produced likewise plenty of potatoes and yams, which supply the want of bread, and are so much the better adapted to these rocks, as agreeing well with a barren soil."6 Craton and Saunders suggest that because the first settlers came from Bermuda, they would have learned the art of making cassava flour from manioc, which would be "more agreeable to European stomachs than that made from Indian corn"7. However the author found no period proof of Bahamians making use of cassava flour. Other islands mention that the Europeans often relied on the natives to make this flour, but, as noted in the history of the Bahamas, the native Lucayan settlers had been mostly (if not entirely) removed from the islands when the Spanish were in charge.

Except for his general comments on vegetables, Catesby has little to say about them, other than potatoes. He seems to have devoted all his descriptive powers to the potato. He calls it an

Photo: Scott Bauer

Varieties of Potatoes, USDA

Agricultural Research Services

excellent root [which] seems to merit the preference of all others; not only in regard to the wholesomeness and delicacy of its food, but for its more general use to mankind than any other root... They being of so easy culture, so quick of growth, and of so vast an increase, that the propagiting it seems more agreeable to the indolence of the Barbarians, than cultivating grains, which require a longer time, with more labour and uncertainty.8

Catesby goes on to list five different kinds of potatoes including the common, Bermudas, brimstone, carrot and claret potato, providing a description of each.

The Common Potato is of a muddy red colour on the outside, but being cut, appears white with a reddish cast; they commonly weigh from half a pound to four, five, or six pounds; usually are long irregularly shaped, and pointed at both ends; this is an excellent kind, and is most planted.

The Bermudas Potato is larger and rounder than the Common, very white within, and covered with a white skin; this is a tender kind, requiring more warmth in keeping, and a different culture from the rest, this is the most delicate sort, but not so much planted as the Common Potato, because of its not keeping so well. This Potato only produces a white flower; the flowers of the other kinds being purple.

The Brimstone Potato grows to a large size, and is shaped like the Common, the colour of it hath given its name, and in goodness it is esteemed next to the Common.

The Carrot Potato is named so, from its colour both without and within, being like that of a carrot; these grow to a very large size, and are of great increase, though of little esteem, being the most insipid [flavorless].

The Claret Potato seems to be propagated more as a curiosity than for any peculiar excellence it hath. The colour of it, without and within, is that of claret [deep reddish-purple].9

These should all sound familiar to anyone who has tried some of the more colorful potato varieties found in grocery stores.

1 Calendar of State Papers Colonial (CSPC), Vol. 19, 1701, Item 655; 2,3, Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol. 1, 1754, p. xxxix; 4 Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 1992, p. 82; 5 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 358; 6 Catesby, vol. 1, p. xxxviii; 7 Craton and Saunders, p. 82; 8,9 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 60

Land Animals and Birds

Cattle was mentioned a couple of times in the previous section on the history of provisioning, but there doesn't seem to have been a lot of cattle in the Bahamas because the people weren't inclined to raise them and the land wasn't especially supportive of cattle. Marc Catesby says these "unhospitable rocky Islands [are] deficient of the numbers and variety of animals that the [American] Continent abounds with"1. He does note that some animals had been brought to the islands including horses,

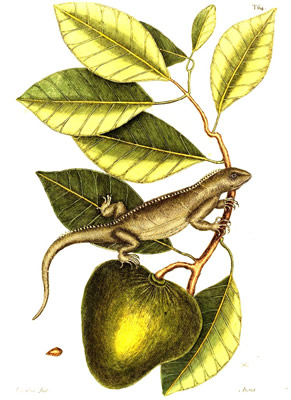

An Iguana, From The natural history of Carolina,

Florida,

and the Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754)

cows, sheep, goats, hogs and dogs, but he elsewhere explains that "[t]he principal food on which the Bahamians subsist, is fish, turtle, and [i]guanas; there are a few cattle, and sheep, but they increase not so much here as in more Northern countries, especially sheep: goats agree better with this climate."2 In addition to iguana, Catesby mentions that the Bahamas contained lizards, land crabs, coneys (usually meaning rabbits, although he is referring here to something else) and rats. He added that there were only nine or ten types of non-migratory birds on the island other than sea-birds.3

Catesby has much to say about iguanas. He begins talking about their eggs, which he notes do not have a "hard shell like the eggs of Alligators, but a skin only like those of Turtle, and are esteemed good food"4. He says that iguanas

are a great part of the subsistance of the inhabitants of the Bahama Islands, for which purpose they visit many of the remote kays and islands, in their sloops, to catch them, which they do by dogs trained up for that purpose, which are so dextrous as not often to kill them, which if they do, they serve only for present spending [immediate eating]; if otherwise, they sew up their mouths to prevent their biting, and put them into the hold of their sloop, till they have catched a sufficient number, which they either carry alive for sale to Carolina, or salt and barrel up for the use of their families at home. ...Their flesh is easy of digestion, delicate and well tasted; they are sometimes roasted, but the more common way is to boil them, taking out the leaves of fat, which they melt and clarify; this they put into a calabash or dish, into which they dip the flesh of the Guana as they eat it.” 5

The Bahamas Coney (Bahamian hutia), From The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the

Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754) He describes an animal he called a 'Bahama Coney' which modern researchers have identified as a Bahamian hutia or Ingraham's hutia. These are a species of rodent endemic to the Bahamas believed to be extinct until one was discovered in the Plana Cays, near Long Island in the Bahamas in 1966. Catesby describes them as being brown and grey and says look like a cross between a rat and a rabbit. He adds, "Their flesh is esteemed very good, it has more the taste of a Pig than that of a Rabbit"6, which may explain why they were nearly hunted to extinction.

Catesby discusses three Bahamian birds which he calls edible: the white crowned pigeon, the flamingo and the yellow-crowned heron. Of the pigeon, he says that they are very populous in the Bahamas, being "of great advantage to the inhabitants, particularly while young: they are taken in great quantities from off the rocks on which they breed."7 He doesn't mention their flavor. He does state that flamingos are "delicate, and nearest resembles that of a Partridge in taste."8 Like authors cited in the other parts of this article, he particularly points to the tongue of the flamingo as a much-desired delicacy.

Crested Bittern (Yellow-Crowned Heron), From The natural history of Carolina,

Florida,

and the Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754)

The bird about which Catesby has the most to say is the yellow-crowned heron which he calls the crested bittern. He explains that they

are of great use to the inhabitants there; who, while these Birds are young, and before they can fly, employ themselves in taking them; for the delicacy of their food. They are in some of these rocky Islands so numerous, that in a few hours, two men will load one of their Calapatches or little boats, taking them perching from off the rocks and bushes; they making no attempt to escape, tho' almost full grown.9

He goes on to note that the islanders call them crab-catchers because the feed primarily on crabs. Despite this, he advises that "they are well-tasted, and free from any rank or fishy savour."10

Catesby talks about one other land-based creature providing sustenance to the islanders: the land-crab [Cardisoma guanhumi]. He explains, " The light-coloured are reckoned best, and when full in flesh are very well tasted."11

1 Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol. 1, 1754, p. xlii; 2 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. xxxviii; 3 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. xlii; 4,5 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 64; 6 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 79; 7 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 25; 8 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 73; 9.10 Catesby, Vol. 1, p. 79; 11 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 32

Fish and Turtle

Not surprisingly, fish were a mainstay of the Bahamian diet. Governor Elias Haskett enthused in 1701, "Here is a great plenty of good fish, and turtle all the year long."1 Naturalist Marc Catesby said that the fish found there "were all of different species from any in Europe,

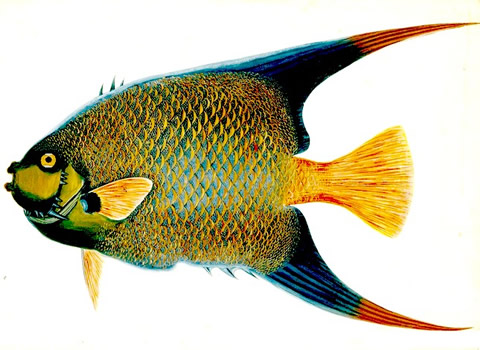

Angel Fish (Queen Angle fish), From The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754)

a few excepted, which are Dolphins, Boneto's, Albicores, Sharks, Flying-fish, Rudder-fish, and Remoras... The universality and numerous shoals of these migratory fish, particularly the three first, are a benefit to mariners in long voyages, affording them comfortable changes of fresh diet, alter long feeding on salt meats."2

Catesby goes into detail on quite a variety of fish he found while visiting the Bahamas. Of interest here are the ones he thought were most edible. Like some of his contemporaries on other islands who described fish, he simply mentions that several of them are 'esteemed' or 'good eating' including mullets3, blue tangs4, red hinds5 and porgies (Sparida)6. He makes similar comments about some of the other fish, adding a bit more detail. He states that pilchards (sardines) are "tolerable good food"7, black margates are "one of the most numerous kinds of Fish frequenting the Bahama islands, and are esteemed very good meat"8, mutton fish (mutton snappers) is valued "for the excellency of its taste it is in greater esteem than any other at the Bahama Islands"9 and queen angelfish are "excellent eating Fish, at the Bahama Islands inferior to none they have."10

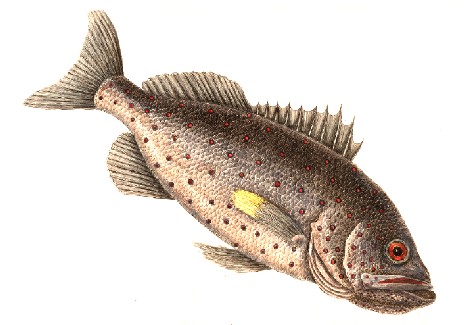

Rock Fish (Yellowfin Grouper), From The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the

Bahama

Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754)

Interestingly, Catesby gives his Rock-Fish (yellowfin grouper) a rather bad reputation, saying it "has the worst character for its poisonous quality of any other among the Bahama Islands". However, he also points out that some of the fish which were found to be poisonous when caught in one place the Bahamas were not poisonous when caught in another.11 In fact, yellowfin grouper are considered to be quite good, being one of the more popular game fish in this area, to the point where they have been so overfished in the Bahamas that they are today considered a threatened species.12 However, they can also be a source of ciguatera toxin poisoning which may explain Catesby's description of their potentially poisonous qualities..

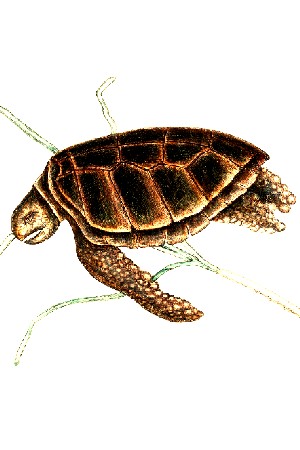

Turtles were a mainstay of the Bahamian Island diet just as they were elsewhere in the Caribbean. Like other authors, Catesby mentions that the green turtle is preferred to the other types, being "esteemed a very wholesome and delicious food"13. He gives a rather extensive and interesting account of the methods used by the Bahamians to hunt them which is included in its entirety here. (Paragraph breaks have been added to this account for readability.)

Green Turtle, From The natural history of Carolina, Florida,

and the Bahama Islands, By Marc Catesby (1754)

In April they [men of the Bahamas] go in little boats to the coast of Cuba, and other neighbouring islands, where in the evening, especially in moon-light nights, they watch the going arid returning of the Turtle, to and from their nests; at which time they turn them on their backs, where they leave them, and proceed on turning all they meet; for they cannot get on their feet again when once turned. Some are so large that it requires three men to turn one of them.

The way by which Turtle are most commonly taken at the Bahama Islands, is by striking them with a small iron peg; of two inches long; this peg is put in a socket at the end of a staff twelve feet in a little light boat or canoe; one to row and gently steer the boat, while the other stands at the head of it with his striker. If the Turtle perceives he is discovered, he starts up to make his escape, the men in the boat pursuing him, endeavour to keep sight of him, which they often lose and recover again by the Turtle putting his nose out of the water to breathe; they pursue him, one paddling or rowing, while the other stands ready with his striker - it is sometimes half an hour before he is tired; then he sinks at once to the bottom, which gives them an opportunity of striking him, which is by piercing the shell of the Turtle through with the iron peg, which slips out of the socket, but is fastened by a string to the pole. If he is spent and tired by being long pursued, he tamely submits when struck to be taken into the boat or hauled a-shore.

There are men, who, by diving, will get on their backs, and by pressing down their hind-part, and raising the fore-part of them by force, bring them to the top of the watery while another slips a noose about their necks13

1 Calendar of State Papers Colonial (CSPC), Vol. 19, 1701, Item 655; 2 Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol. 1, 1754, p. xliii; 3 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 6; 4 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 10; 5 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 14; 6 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 16; 7 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 24; 8 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 2; 9 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 25; 10 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 31; 11 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 5; 12 'Yellowfin grouper', wikipedia.com, gathered 5/20/20; 13 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 39

Imported Food

Much of the food the Europeans in the Bahamas relied on was imported. As mentioned, some wheat was imported from the colonies to make bread1.

Nassau Harbor, Bahamas with Small Boats, From New York, Nassau

and West India Mail

Steamship Line Promotional Material (1877)

Carolina governor Nathaniel Johnson reported in September of 1709 that they exported beef, pork, rice, butter and Indian peas to the Bahamas and other Caribbean islands.2 Bahamian resident John Graves provided a list of prices for such commodities in the Bahamas in1708 which included "Mutton, Veal, Pork salt and fresh, at Nine-pence per Pound; Beef from Nine pence to Six-pence; Butter Eighteen-pence; Milk Six-pence per Quart; Eggs Three-half-pence a-piece; all other Provisions proportionable"3.

On the other side of the bargaining some provisions were exported from the Bahamas to the colonies. Governor George Phenney explained in a report of March, 1723, "Our present inhabitants being mostly seafaring men, the trade chiefly consists in cutting the dye woods, which with the salt, oyl, turtle and turtle shell and fruits are exported to the neighbouring Colonys, for which sometimes the vessels belonging to No. America bring in barter several comoditys, etc."4 Naturalist Marc Catesby added the Bahamas "supply Carolina with salt, turtle, oranges, lemons, &c."5 He elsewhere mentioned that iguana were exported to Carolina.6 However, turtle and fruit seems to have been their primary food exports. However, Catesby echoed Phenny's comment, noting that "the greater number of the Bahamians content themselves with fishing, linking of turtle, hunting Guanas"7 for their food, not bothering to market the production of the islands to other places.

1 Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol. 1, 1754, p. xxxix; 2 Calendar of State Papers Colonial (CSPC), Vol. 24, 1708 - 1709, Item 739; 3 John Graves, A Memorial or a Short account of the Bahama-Islands, 1708, p. 7; 4 CSPC, Vol. 33, 1722 - 1723, Item 455.vii; 5 Marc Catesby, The natural history of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Vol 2, 1754, p. xxxviii; 6 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. 64; 7 Catesby, Vol. 2, p. xxxviii