Barbados Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Barbados Page 1

Barbados was one of the oldest English-possessed

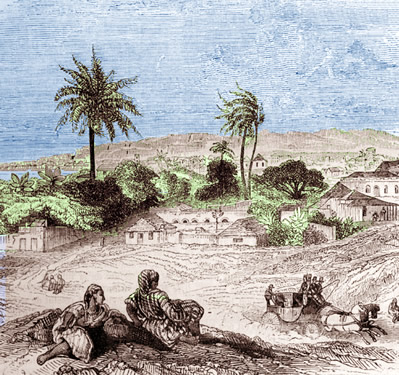

Cartographer: Richard Ford

Taken From "A New Map of the Island of Barbados" Showing Plantation Locations By Owner (1676)

islands in the Caribbean, primarily because it was unoccupied when they arrived on it in the early 17th century. It was an important site for English ships involved in the triangle trade; Barbados was the island many ships made for when crossing the Atlantic. Depending on the length and eventfulness of their crossing, it would be necessary for merchant and naval vessels to refit and re-victual. here. Much of the island was settled in the mid-17th century and by the 1660s sugar growing had overtaken most of the land (see the map at left which shows the locations of the plantations on the island). Barbados sugar was well regarded and as the sugar market soared, the planters converted their property to producing it. As time went on, the larger planters began consolidating their holdings by buying up the smaller plantations in the 1670s and 1680s, resulting in more and more land being devoted the production of sugar at the expense of other produce.

By the golden age of piracy, Barbados was still an important initial stop for many merchant ships, particularly slavers bringing Africans in to work on the plantations, but Jamaica had superceded it as a victualling location. Nevertheless, there are several accounts from around this period of sailors' victualling their ships on this island. Being so well established as a British territory, there are a couple of English accounts of what foodstuffs this island offered. Coupled with Jamaica, much of what is known about food grown during this period in these areas comes from contemporary accounts of people living on these two islands.

Barbados History Related to Food

During the golden age of piracy, merchant ships coming from Africa, either after slaving or

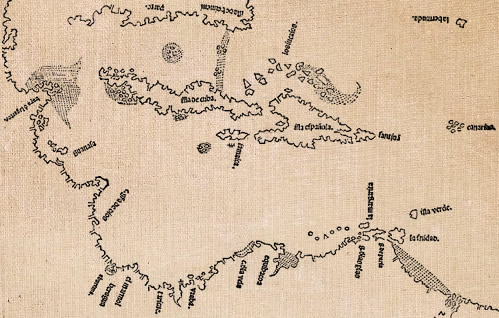

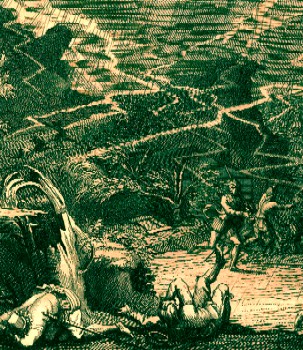

Cartographer: Pietro Martire d'Anghiera - Map of the Caribbean (1511)

sailing down the coast to make the journey across the Atlantic often made for Barbados. There they could sell some or all of their cargo and obtain provisions as well as recover from scurvy if the voyage had been long enough to cause it. Much of Barbados was planted with sugar cane rather than edible plants which could be sold to ships arriving in port because sugar was the better money-maker.

The date of the first European discovery of Barbados is unclear. Most historians agree it would have been found by the Portuguese in their journeys to and from their settlement in Brazil, which they had discovered in 1501. One source claims it appears on an unnamed Spanish map in 15111, almost certainly referring to Pietro Martire d'Anghiera's map of the Americas found in P. Martyris Angli Mediolanensis Opera. Barbados may be included on this map (seen at right), although the island is not mentioned by name. (However, this map does name other islands discussed in this article including Jamaica (near the center) and the Canary Islands (center right). It is also the first known figuring of Bermuda (labeled upside down, top right).)

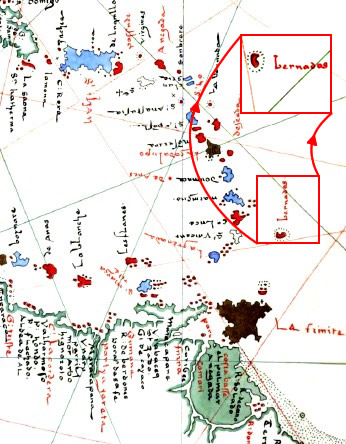

Author Robert Schomburgk traced a copy of a map of the world on a plane scale in vellum with names in French (part of which is seen at left), which is held by the British Museum (in additional manuscripts 5413).

Traced by: Robert Schomburgk

The Caribee Islands, Traced From 'a Manuscript of the Chart of the

World' (c. 1536),

From The History of Barbados, p. 254 (1848)

Schomburgk says, "According to the catalogue it is considered to have been executed in the times of Francis the First for his son the Dauphin" and the symbols on the map indicate that it was made some time before 1636.2

Another early map which names Barbados is an illustrated manuscript called the Boke of Idrography (aka. the Rotz Atlas) written by hydrographer Jean Rotz, dated to about 1535-1542. Schomburgk's map is similar to the Roke Atlas map of the area found on folio 23v. However, there are a variety of differences including the color and spelling of the name of the island. Schomburgk's tracing shows it in red as 'bernados' while the manuscript shows the island colored in brown and labeled "barbudoss". Of the author of the manuscript, the British Library says, "Jean Rotz, [was a] hydrographer and navigator of Dieppe, who probably took part in the expedition from Dieppe to Sumatra under the command of Jean Parmentier in 1529–30, and in 1539 travelled to Guinea and Brazil."3 This would put the naming (and thus discovery) of the island by the Portuguese to before 1530. They named it "Las Barbadas", which naturalist Griffith Hughes suggested in 1750 meant 'the Bearded Islands'. He explains that the name might refer to the fig trees found on the coast of the island, from whose branches "hang innumerable small Filaments growing down-wards, till they touch the Earth, and then take Root. These Thread-like Resemblances have been called by the English, from the first Settlement of the Island to this Time, the Beards of the Fig-trees"4.

Whatever the date of its discovery, the Portuguese were clearly aware of Barbados' existence in the mid-16th century, although they never settled it. John Oldmixon wrote in 1708, "the Portuguese were the first who discover’d it, and it lying convenient for their stopping in their Voyages to and from the Brasily, they left some Hogs here, which multiply'd, according to the general Report of Writers, so prodigiously, that when the English came hither, they found the Isle over-run with them."5

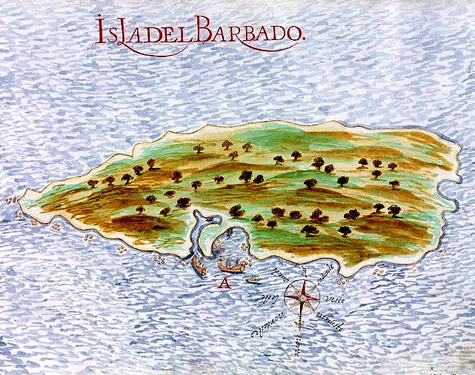

Artist: Nicolas de Cardona - Barbados, From Descripciones geográphicas e hydrográphicas (1632)

John Poyer suggested in the early 19th century that "Curiosity, or the want of refreshment, probably induced their nearer approach; but the rude, uncultivated aspect of the country, which they found without inhabitants, and destitute of every article necessary for human accommodation, was little calculated to induce these travellers to remain long on a spot incapable of yielding those advantages which were then the principal objects of European pursuit in the western hemisphere."6

The first English vessel recorded as stopping on Barbados was the 'Oliph Blossome', sponsored by Sir Olive Leigh, on August 14, 1605. William Turner, a man aboard the ship, reported that the island was "barbarous without any inhabitants, having great store of Hogges, Piggeons, and Parrats."7 This is not a particularly promising description of the usefulness of the island and no settlement was proposed as a result of that journey.

The reason for the first English settlement can be traced back to William Courten, although the details vary. One source suggests that it was inspired by a report given by Dutch around 1623 or 1624 when the Spanish first allowed them trade with Brazil.8 The Dutch "landed in Barbados on their return to Europe, for the purpose of procuring refreshments. On their arrival in Zealand they gave a flattering account of the island, which was communicated by a correspondent to Sir William Courten, a merchant of London, who was at that time deeply engaged in the trade with the New World."9 Another source similarly suggests that the ships were actually Dutch men-of-war, "which had been employed on a secret expedition against the Spaniards."10 Courten's brother Peter was in Zealand and he told William that Barbados was "not inhabited by any nation, of a good soyl, and very fit for a plantation."11 A third account explains that one of Courten's ships on a privateering voyage against the Spanish12, "returning from Fernambock [Pernambuco] in Brasil, being driven by foul weather upon this coast chanc'd to fall upon this Island... which they found by tryals in several parts, to be so overgrown with Wood, as there could be found no ...Savannas for men to dwell... [finding] only Hogs [living there], and those in abundance."13

However it happened, William Courten became interested in Barbados and "the fertility and commodious

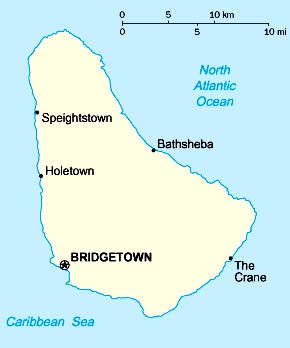

Major Cities of Barbados, CIA Factbook (2005)

situation confirmed him in his plan of forming a settlement in Barbados."14 Having heard some of these good reports, James Ley, Earl of Marlborough applied for a patent from King James I to secure the rights to the island. Under Lord Ley's protection, Courten fitted two ships with the tools required to establish a settlement on Barbados. Only one successfully made the voyage - the William and John, commanded by John Powell - resulting in 30 men landing on the island on February 17, 1625. They established James Town in honor of the king, a location which has since been renamed Holetown.15

Back in England, James Hay, the Earl of Carlisle, learned of this new West Indies community and became incensed, he being a favorite of James I and having obtained a warrant for a grant of all the Caribbean islands under the name Carliola. Hay had initially been interested in settling St. Christopher's before learning of this. Because of Courten and Lay's actions, he pressed King Charles I to confirm his grant of all the Caribbean Islands (James I had died in 1625). Lay opposed the grant "which produced a tedious litigation."16 In the end, Charles I granted Hay's warrant in 1627, giving him rights to Barbados.

Hay contracted with a group of London merchants to send their own group of 64 men to settle the island in 1628 under the leadership of Charles Wolferstone. "Each of these settlers was entitled, on his arrival, to one hundred acres of land. They fixed their residence in the vicinity of [Carlisle] bay, where they built houses for the reception of their stores"17 along with a bridge to cross what is today the Constitution River, resulting in the city being named Bridgetown. By this time, "Courteen's settlement was in a very promising condition. They had cleared a considerable quantity of lands which were let at an easy rate; and so great was the fertility of the soil, that Barbados bade fair, in a short time"18.

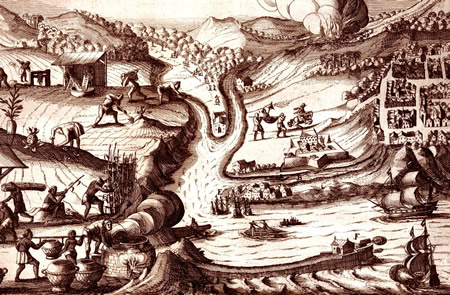

Artist: Pieter van der Aa - Barbados, From Les Forces de l'Europe, Asie, Afrique et Amerique (1726)

There followed a great deal of back-and-forth between these two communities eventually resulting in Courten's men being brought into the Carlisle's fold by the end of 1629.19

Under this regime, rules were established and a variety of men were appointed to govern the island. The island flourished between 1630 and the start of the civil war in England. In 1636, there were 766 people with 10 acres or more of land.20 By 1647, the "population had encreased to the amazing extent of fifty thousand persons of both sexes; and the value of land had encreased in proportion to the number of inhabitants."21 The civil war distracted those in England who had been fighting over the ownership of the island and taxation of the people (who were regarded as 'at will' tenants of the Earl of Carlisle). "In the turmoil of factions Barbados was forgotten, and left to itself its trade remained unrestricted. This freedom caused the island to prosper, and it was visited both by Dutch and English ships."22 Many of the planters with large holdings of land were able to accumulate fortunes.23

Francis Willoughby was made governor of the island in 1650. Upon his arrival in May of that year, "he found it flourishing, and populous, and most of the principal planters extremely well-affected to the royal cause; so that they embraced

Bridgetown, Barbados, From Le Magasin Pittoresque, p. 17, (1840)

it with incredible ardor."24 Willoughby made Humphrey Walrond his Deputy Governor and under Walrond a variety of laws were passed to continue the island's prosperity, including "an act ...for the encouragement of such 'as shall plant or raise provisions to sell.'"25 In addition to spurring investment in the planting of sugar, this would have inspired the raising of food to be sold to ships coming into port for victuals.

Barbados' prosperity was about to take several hits, however. In 1651, the English parliament passed the act of navigation, which prohibited foreign ships from trading with English colonies. While some of the the money and slaves flowing into Barbados came from English ships, much of it was a result of the sale of sugar to the Dutch. They petitioned the States General to encourage the English to restore free trade. The people of Barbados likewise complained to England. Neither the Dutch nor the English planters were successful and the law remained in place for almost two hundred years, damaging the Barbadian trade.26 Further discouraging sailors from staying in port, when Daniel Searl was appointed governor in 1652, he passed "an act to prevent frequenting of taverns and alehouses by seamen; an act for the keeping clear the wharfs, or landing-places, at the Indian-Bridge, and on Speight's-Bay, alias Little Bristol"27.

On top of these legal maneuvers discouraging their trade, there were a series of natural disasters on Barbados in the decades that followed. A fire occurred in Bridgetown in 1666, although the burned buildings were "rebuilt in a more substantial manner."28

Artist: Pieter van der Aa

Hurricane Strikes Land in the Caribbean (1707)

A hurricane hit the island in 1675, "which besides killing great numbers of people, and blowing down three hundred houses, had so effectually destroyed their plantations and works, that they could make no sugar for two years. The corn was destroyed, and eight ships cast away in the harbour."29 To make things worse, the North American colonies "upon which Barbados depended for her supplies, were not in a state to furnish either provisions or timber in sufficient quantities. Credit failed, and numerous families who had formerly lived in opulence were obliged to retire in order to escape their creditors."30

Historian Richard Slator Dunn says that the need of the Barbadian planters for sufficient food and drink "posed a major problem for seventeenth-century Englishmen in the West Indies. The food crops they were used to in England could not be grown in the Caribbean, for the most part, and those food crops that flourished in the Caribbean were generally unappealing to the English palate."31 He notes that early residents made do, purchasing salt fish and meat and dairy products when they were able from English merchant ships. "Once the planters in these small islands converted their prime acerage to sugar cultivation, they no longer had enough land left for provisions crops to feed themselves and their slaves. After 1650 or 1660, the Barbadians and Leeward Islanders were forced to import most of their food from England, Ireland and North America."32 If true, this means that it was unlikely that many harvest crops were sold to ships. Contrary to this notion are comments from Richard Ligon who lived on the island around 1650. He states that planters, even those growing sugar, kept part of their land for growing food 'for table' along with a list of foods he enjoyed while staying on Barbados which will be explored in the section on foods found on the island.

As if these challenges were not enough, James II increased the duty on Muscovado [unrefined] sugar in 1685.

Dutch Sugar Plantation in Brazil, From Reys-Boeck van het rijcke Brasilien (1624)

"This burden considerably reduced the value of the plantations [in Barbados], and as the French colonists in Guadaloupe and Martinique, and the Portuguese in Brazil, had greatly extended the cultivation of sugar, they became formidable rivals; the more so as they were able to produce sugar at thirty per cent. less expense than the British sugar-planters."33 James had unwittingly promoted sugar production by competing countries over those of his colonies. Although he abdicated in 1688, the law remained in effect until it expired in 1693.34

Another factor leading to the decline of Barbados during this period was the English taking Jamaica. Generals Venables and Penn arrived at Barbados in 1655 to strike at the Spanish. "They were supply'd with several Necessaries at Barbadoes, where Hundreds of Volunteers join'd them" along with 1300 more from St. Christophers and Nevis.35 They first attacked Santo Domingo on Hispaniola in an attempt to capture it, but were forced to retreat. They then headed for Jamaica where they were successful. Although it took several years to promote interest in the new colony, by 1660, the population of Barbados began to decrease as it citizens moved to other Caribbean locations, particularly Jamaica. "Allured by the prospect of greater advantages on a theatre so much more extensive, many opulent planters and other adventurers removed to Jamaica, where land could be procured in greater plenty, cheaper, and with less difficulty."36

1 "Barbados", mapsland,com, gathered 2/25/20; 2 Sir Robert Schomburgk, The History of Barbados, 1848, p. 256; 3 "Royal MS 20 E IX", British Library Website, bl.uk, gathered 2/26/20; 4 Griffith Hughes, The Natural History of Barbados, 1750, p. 2; 5 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Vol. 2, 1708, p. 2; 6 John Poyer, The History of Barbados, 1808, p. 2; 7 Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes, 1906, p. 352; 8 "The History of Barbados", The Modern Part of An Universal History, 1764, p. 131 & Schomburgk, p. 258; 9 Schomburgk, p. 258; 10 John Poyer, The History of Barbados, 1808, p. 5; 11,12 Nicholas Darnell Davis, The Cavaliers & Roundheads of Barbados, 1650-1652, p. 23; 13 Richard Ligon, A True And Exact History Of the Island of Barbadoes, 1673, p. 23; 14 Schomburgk, p. 259; 15 Poyer, p. 6-7; 16 Schomburgk, p. 261; 17 Poyer, p. 20-1; 18 "The History of Barbados", p. 132; 19 Schomburgk, p. 264; 20 Poyer, p. 32; 21 Poyer, p. 38; 22 Schomburgk, p. 268; 23 Poyer, p. 34-5; 24 "The History of Barbados", p. 139; 25 Schomburgk, p. 286; 26 Schomburgk, p. 272; 27 "The History of Barbados", p. 143; 26 Schomburgk, p. 293; 29 "The History of Barbados", p. 150; 30 Schomburgk, p. 293; 31,32 Richard S. Dunn, Sugar and Slaves, 2000, p. 272; 33 Schomburgk, p. 299; 34 George Louis Beer, The Old Colonial System, 1660-1754, Part 1, 1913, p. 167; 35 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 268; 36 Poyer, p. 66-7

Ships Victualling At And Near Barbados

There are several examples of ships victualling at, or, in the case of some pirates, near Barbados. From the English navy, we have the accounts of sea surgeon John Atkins from HMS Swallow and Weymouth escorting slave ships in August of 1722. His talks particularly the price of salt meats and biscuit bread available for sale to incoming ships.1

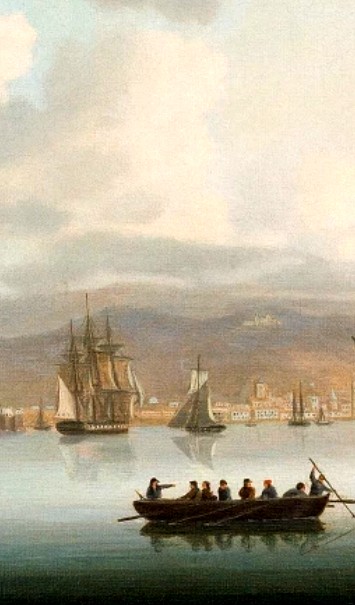

Artist: Thomas Buttersworth - Ships in Port (18th-19th century)

Several sailors on merchant vessels mention procuring food on Barbados. Edward Barlow was as chief mate of the Guannaboe West Indiaman, which stopped there in 1678. He states that Barbados "produceth several fruits for the use of the inhabitants" and goes on to list a variety of fruits and vegetables.2 Sailor Clement Downing mentions two different English navy vessels visiting the island in early 1723 on their way back to England from the East Indies. The first, the Exeter, "was obliged to touch for want of Provisions"3 at Barbados on her way back home to England. The second, the Salisbury, "after a Consulation of the Officers, [decided] to steer for Barbadoes, in order to refresh the Ship's Crew, with Provisions, Wine and Water."4 It seems the provisions aboard the Salisbury had not been very good and they officers hoped to improve morale by obtaining better at the island.

Two golden age pirates were around Barbados taking ships for food, although they were not actually on it according to these accounts. While Barbados was visited by navy ships, there were few English vessels assigned to protect the Caribbean during this period. Since Jamaica was the primary supply point for these vessels, Barbados was not as well guarded by the navy and the pirates knew that ships leaving the island would have refreshed their victuals and taken on goods, making them good potential targets.

The first example of pirates taking food (as well as other things) comes from the exploits of Bartholomew Roberts' pirates who sailed from La Désirade, Guadeloupe to Barbados around September of 1720 where "they fell in with a Bristol Ship of 10 Guns, in her Voyage out, from whom they took Abundance of Cloaths, some Money, twenty five Bales of Goods, five Barrels of Powder, a Cable, Hawser, ten Casks of Oatmeal, six Casks of Beef, and several other Goods"5. The other example comes from the New England Courant which reported in September of 1721 "that a Pirate Ship of 24 Guns which came from the Coast of Guinea, lay to Windward of that Island [Barbados], and had taken a Brigantine bound thither from Boston, but took nothing from them but some Provisions."6

1 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 205 & 208-9; 2 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 312; 3 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 98; 4 owning, p. 99; 5 Charles Johnson, A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Shonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 215; 6 New England Courant, 9-4-21 - 9-11, Issue 6