Jamaican Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning - Jamaica, Page 1

Jamaica was the premiere location for provisioning English navy, merchant and privateer ships in the Caribbean during the golden age of piracy. It was better suited for growing a wide variety of foods than the next-best candidate, Barbados, and more developed than any of the other British-occupied Caribbean islands. It has already been shown that the navy established their first Caribbean victualling outpost there, informally in the 1660s, then more formally in 1688.

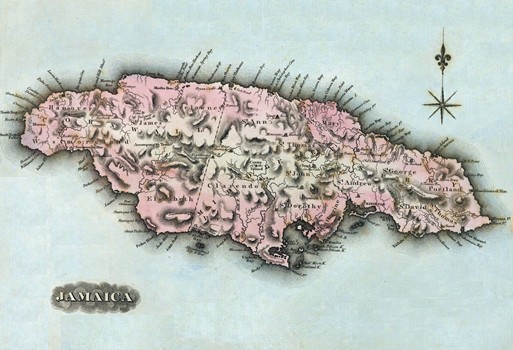

Cartographer: Fielding Lucas - Map of Jamaica (1823)

Because Jamaica was so important to the English, there are several contemporary accounts of the island with extensive accounts of the flora and fauna there, resulting in a wealth of written material about the foods found on the island. These accounts include cartographer Richard Blome's A Description of the Island of Jamaica of 1672 which relied on information provided by Thomas Lynch and others living on the island, Hans Sloane's account of his time living there from December 1687 - February 1689 in his book A Voyage to the Islands Madera, Barbados, Nieves, St Christophers and Jamaica, mathematician and chemist John Taylor's journal of his time at Jamaica during December 1686 through May of 1688 recorded in the book Jamaica in 1687 and Charles Leslie's firsthand account of his time on the island around 1720 found in A New History of Jamaica in thirteen Letters. The information found in these books coupled with that found in the previous section about Barbados make up the majority of the detailed English accounts of foods to be found on such islands.

Jamaica, particularly Port Royal, is often associated with pirates. While it was certainly a place for the buccaneers to refit and re-victual their ships during the 1660s and, to a lesser degree, the 1670s, by the 1680s nearly all Jamaican-based buccaneering had ceased and the island became much more 'civilised'. By the beginning of the golden age of piracy in 1690, Jamaica was no longer relied upon by the pirate community; much of their victualling activity in the Caribbean had moved to the Bahamas, which were nearly unregulated during this period.

Jamaican History Related to Food

There are basically three phases of history on Jamaica before the golden age of piracy. The first was before the arrival of the Europeans, when the Taino natives (Arawaks) were on Jamaica, possibly having inhabited at the point it for over 2500 years. They called the island 'Xaymaca' (land of wood and water”).1 Little was recorded about their time there. The second phase was the discovery and occupation by the Spanish until 1655. The third phase was the capture of the island by the English in 1655 who remained there throughout the golden age of piracy.

Jamaican History Related to Food - The Spanish

Artist: Albert Bierstadt

A Fanciful Image of Columbus Landing (c. 1893)

The second phase was the discovery and settlement of the island by the Spanish between 1494 and 1655. The island was discovered by the Europeans during the second voyage of Columbus on May 4, 1494, who "thought it the most beautiful of any island he had yet seen in the West Indies, and was astonished at the multitudes of people who came off to the ships in large and small canoes."2 The next day they landed at what is today St. Ann's Bay, calling it Santa Gloria and calling the island Santiago. They explored the island, looking for good harbors.3 Although some of the Taino fired arrows at them when they refused to leave, "afterwards many natives came off to the ships in a peaceable manner to see our people and to barter provisions and other articles for such trifles as our people offered."4 The Europeans left the island on May 15th, but returned on July 22nd after exploring Cuba. They found the island "most delightful, and very fruitful, with excellent harbours at every league distance. All the coast was full of towns, whence the natives followed the ships in their canoes, bringing such provisions as they used, which were much better liked by our people than what they found in any of the other islands."5

Columbus returned to Jamaica after exploring Central America on his fourth voyage to the West Indies in May of 1503. He arrived first at a site he called Puerto Bueno, but finding no water, he sailed

Artist: Girolamo Benzoni

Natives and Spaniards, From America pars Quarta (1594)

his remaining two ships to Santa Gloria. Their poor condition caused them to start to sink, so the sailors ran the ships ashore at Santa Gloria, where they were to remain cast away for over a year. Regarding provisioning during this stay, Columbus says,

the Indians, who were a peaceable good-natured people, came in their canoes to sell provisions and such things as they had for our commodities. ...It was the good providence of God which directed us to this island, which abounds in provisions, and is inhabited by a people who are willing enough to trade, and who resorted from all quarters to barter such commodities as they possessed.6

They depended on the natives to supply them with food during their long stay.

In 1508, the Spanish government gave Jamaica to Columbus's family in the person of Diego. Some time after, the king granted a concession to Diego de Nicusa to use the island for 'slaves and provisioning' in outfitting an expedition to Panama. This was contested by Columbus's son Diego who was able to keep his claim to the island.7 Columbus' son appointed Juan de Esquivel to be his Lieutenant in Jamaica. Esquivel settled with 80 men and their families near Santa Gloria, calling their town Sevilla la Nueva [the New Seville]. The settlers were given permission to enslave the Indians who were used as laborers in jobs such as farming. As the Indians died off under their harsh treatment, the Spanish began importing African slaves around 1513 to replace them.

Two years later, Francisco de Garay, arriving with more settlers which included farmers and livestock. Not liking the site of Sevilla la Nueva, he established a new town nearby with 500 men and their families which he named Sevilla in 1518. The town was again moved in 1534 to the present present site of Spanish Town, being called

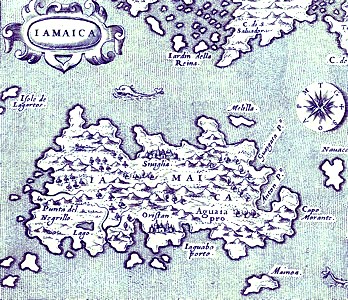

Cartographer: Tommaso Porcacchi

Map of Jamaica, From Isolario (1576)

Villa de la Vega.8 Eighteenth century English historian John Oldmixon said of this town and its inhabitants, "on the Product of a rich Country; all that they took Care for, was a little Sugar, Tobacco, and Chocolate. A few Vessels came to them sometimes, to the Masters of which they sold their Hides, Tallow, Pepper, and Coco-Nuts, but in no great Quantities. Yet, for the Possession of a Place ...they would not be at the pains to cultivate"9. (Oldmixon's account is rather biased against the Spanish and this statement should be considered in that light.)

In 1537, Luis Colón [Columbus], grandson of Christopher, was made the third Admiral of the Indies, renouncing this position for a 10,000 ducat annuity. He retained Jamaica as one of his estates, with the title 1st Marquess of Jamaica, keeping it until his death in 1572. He levied heavy taxes on the settlers. Diego Colón de Toledo y Pravi married Luis's daughter Felipa, making him the fourth Admiral of the Indies until his death in 1578. He was succeeded by the fifth admiral of the Indies, Don Christoval Columbus de Cardona, Duke of Veragua, Marquies of La Vega and of Jamaica, who died without heir in 1583. There was a great deal of litigation after this and the ownership of the island becomes tangled. Jamaica was not a contented island under their ownership.10 Author Charles Leslie notes that Columbus's descendents "used the utmost Severity in collecting the Stints which they had imposed... by such cruel and rapacious Methods, the Colony became rather on the decline; few chose to settle where they were sure to be oppressed; and those who had Effects removed to other Places, where they might enjoy the Fruits of their Toil and Industry."11

Artist: Dominicus Custos

Anthony Shirley, From Atrium heroicum

Ceesarum (1600-2)

In an expedition begun in 1596, Anthony Shirley raided Jamaica in January, 1597, plundering the inhabitants and burning Spanish Town, meeting with little resistance from the residents. "The oppressed Planters had little at Stake, and would have been fond of changing Masters, and becoming Subjects to any Prince that would have allowed them to live easy and free"12. Shirley had no interest in staying in Jamaica, however, so the Spanish resumed their rule after he left. At that time, "the Governor relaxed something of his former Severity, and the People appeared more easy and content"13.

The town was again sacked by English privateer William Jackson along with about five hundred sailors in the Charles, Dolphin and Valentine in March, 1643, at which time Jamaica was said to be home to about 2000 Spaniards.14 He left after ransoming Spanish Town for "200 Beaves [cattle] and 10,000 weight of cassavi bread for ye victualling of our ships, besides 20 Beaves every day for ye general expense till our departure and 7,000 pieces of Eight."15 He spent 16 days on the island salting the meat in preparation for leaving. "But Jamaica's fertility impressed Jackson, and his men liked the island so much that 23 deserted to the Spaniards."16 His report on the island's resources and lack of protection was instrumental in the English decision to capture the island twelve years later.

1 "The History of Jamaica", Jamaica Information Service website, gathered 3/10/20; 2 Robert Kerr, A General History and Collection of Voyages, Vol. 3, 1811, p. 115; 3 "Seville Heritage Park", whc.unesco.org, gathered 3/10/20; 4 Kerr, p. 116; 5 Kerr, p. 122; 6 Kerr, p. 225; 7 Henry Rose Carter, Yellow Fever - An Epidemiological and Historical Study of Its Place of Origin, 1931, p. 162-3; 8 "Seville Heritage Park", gathered 3/10/20; 9 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 267; 10 For more on the ownership of Jamaica, see John Boyd Thacher, Christopher Columbus, His Life, His Works, His Remains, Vol. III, 1904, pp. 632-4 & G. A. Thompson, The Geographical and Historical Dictionary of America and the West Indies, Vol. II, 1812, p. 290; 11 Charles Leslie, A New History of Jamaica in thirteen Letters, 1741, p. 40; 12,13 Leslie, p. 42; 14 Leslie, p. 43 & Frank Cundall, Historic Jamaica, 1915, p. 46 & 82; 15 Cundall, p. 82; 16 Jan Rogozinski, Pirates! - An A-Z Encyclopedia, 1996, p. 171;

Jamaican History Related to Food - The English

Naval Attack in the Caribbean, From Amerikaanse

Zeerovers, By Alexandre Exquemelin (1678)

The third phase of Jamaican history began when the English captured the island from the Spanish in May of 1655. It was taken by Admiral William Penn after he and his forces failed to take their original target, Hispaniola. According to a soldier's narrative of the engagement, the Spanish called for a truce, which was agreed upon, after which "the enemie sent us 300 head of leane cattle, on purpose to make the least of the country."1 Oldmixon explains that "the English possess'd themselves of all the South and South-East Parts of the Island: A Regiment was seated about Port Morant, to plant and settle there, and others in other Places; over whom Col. Doyly [Edward D'Oyley] was left Governour, with between 2 and 3000 Land-Forces, and about 20 Men of War, commanded by Vice-Admiral Goodson [William Goodsonn]."2

Some of the Spanish surrendered, others hid in the hills, driving the majority of their cattle there, so that "the English troops found themselves on a sudden extremely destitute of food in this land of plenty, for they could procure no fresh meat except at the point of their swords."3 Jamaican Historian Edward Long notes that the soldiers stationed on the island ate "the refuse of the naval provisions, putrid salt beef, and rotten biscuit, at a short allowance [meals for four men being served to six], with no other liquor [liquid] for dilution than the turbid water of the Rio Cobre."4 In trying to support his troops, major-general Richard Fortescue asked Cromwell to send them bread, oatmeal, brandy, medicines, and other necessaries as well as Scottish servants to help them with planting crops.5

After the island was taken by the English, Thomas Modyford, then a planter on Barbados, said of Jamaica, "If this place... be fully planted, his highness may do what he will in the West-Indies."6 Robert Sedgwick, one of the men appointed by Cromwell to serve as a civil commissioner in the Jamaican government said, "The island is adapted to produce any kind of merchandizes that other islands do."7 However, many other Englishmen living in the Caribbean worried that Jamaica would drain their islands of workers and ruin the market for planted commodities such as sugar. "For this reason, and others, they obstructed the planting of it to the utmost of their power, and intimidated their inhabitants from passing over to settle there, by representing it as a certain grave to all such adventurers."8

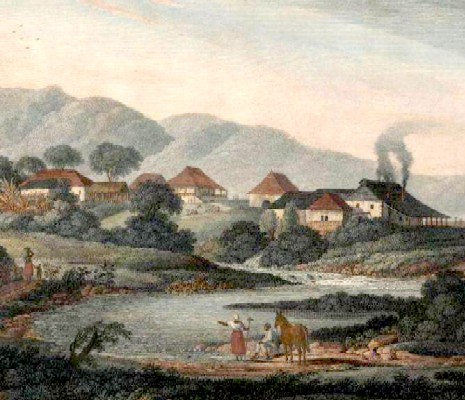

Artist: George Robertson - William Beckfords Roaring River Estate, Jamaica (1773)

The English soldiers residing on the island, many of whom had formerly been planters, were supposed to farm the rich land of Jamaica. Each man was assigned land to plant, but they resisted doing so. Commissioner Sedgewick complained that they had killed most of the cattle which had not been driven away by the Spanish. "Our soldiers have destroyed all sorts of fruit, provision, and cattle; nothing but ruin attends them wheresoever they go. If some good encouragement was given to increase planters here, it might be well; but, as the case stands at present, there can be nothing of that kind. ...The soldiers desire, either to be employed in arms, or sent for home again: dig or plant they will not; but would rather starve than work."9 The driving force against settling and farming were a group of army officers believed that by wasting the provisions being sent to support them, Cromwell would get tired of the expense and send them all back to England.10 Nevertheless, vice-admiral William Goodsonn published a document directing the soldiers "to put some provision in the ground, thereby to prevent and avoid inevitable ruin", proposing to give each soldier the land he had been assigned previously. Then the government "would issue out feed, such as pease, Indian corn, and the like, and bind themselves to the observance of this compact as an absolute law"11.

The soldiers remained resolute in their resistance, expecting to be supplied with food from the stores brought to Jamaica aboard ships. When that food began to run out in 1656, they mutinied, still refusing to plant.12 When colonel William Brayne arrived on the island in December of 1656 with reinforcements, he learned that certain officers were discouraging the soldiers from planting because they didn't want to be there. He "very wisely gave leave to the most turbulent, discontented, and worthless among them, to return to England; an offer which they most willingly embraced. ...after their departure, the soldiers, now no longer perverted from husbandry, applied themselves readily to work."13

To further increase planting on the island, about 1600 people and servants arrived on Jamaica in late 1656 from Nevis intending to establish plantations. "The example of these Nevis planters gave a surprizing turn to the sentiments of the New-Englanders. They now began to think, that the reports in prejudice of Jamaica had been greatly exaggerated; and that it must be a desirable place

Artist: Edward Barlow - Spanish Town, Port Royal and Kingston Harbor, Jamaica (c. 1677)

which could attract so many persons, and induce them to forsake their established settlements."14 When the soldiers realized how well-suited the environment was for crops, they they began to farm and decided food delivered from outside the island for their support was no longer needed.15

It was under Brayne that Port Royal was established beginning in 1657. On Port Royal Point, he built storehouses for the army and navy with trade in mind.16 In September 1657, D'Oyley was put in charge of the military on the island. He strengthened two makeshift forts which had been begun previously and built a third to safeguard the town. Because the navy gradually withdrew from the island, he invited the buccaneers on Hispaniola to serve as their navy in exchange for making them privateers through the issuance of letters of marque.17

There was something in D'Oyley's choice of defenders;

Port Royal and Kingston Harbor (1782)

Long says the buccaneers were one of the primary reasons Jamaica was able to remain an English possession despite attempts by the Spanish to regain the island. Combined with the defences at Port Royal, the actions of the buccaneers kept the Spanish busy trying to defend their West Indies colonies.18 However, as Charles Leslie pointed out, "the indelible Stain of Pyracy sullies their great Actions, and makes them looked upon as Disturbers of Mankind, and Villains, who are only famous for Murder and Robbery. …Jamaica ...was the common Resort of the Pyrates [buccaneers]; there they were sure of Protection, and whatever Necessaries they wanted; the Governors and Planters encouraged their Expeditions, and took care to supply their Vessels."19 Oldmixon adds, "the Government of Jamaica, tho they were far from encouraging any such wicked Courses, yet wink'd at them, in Consideration of the Treasures they brought thither, and squander'd away there."20

The Jamaican government continued to subtly support the buccaneers up until the English government signed the Treaty of Madrid in July of 1670, officially recognizing their right to hold the territories they had successfully taken in the West Indies including Jamaica. Henry Morgan completed his last Spanish raid on Panama in January of 1671, allegedly not having heard that a treaty had been signed prohibiting such action.

The richness of the island's produce and the cheapness of the land

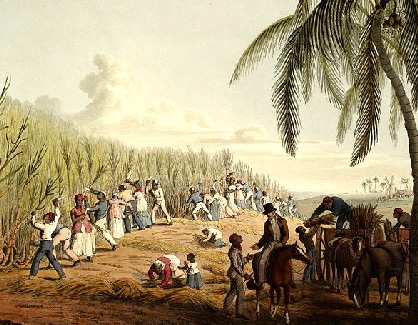

Artist: William Clark

Cutting Sugar Cane, Ten Views in the Island of Antigua (1823)

there continued to encourage experienced planters to defect from other islands such as St. Kitts, Nevis and Barbados and apply their expertise to the land of Jamaica during the mid-17th century. Thomas Modyford left Barbados and settled on Jamaica in June of 1664, "where he set about Improvements, and shewed the Planters a fair Way of getting soon rich; he taught them how to order the Sugar-cane... with the greatest Good-nature, gave them all the Insight he could into the Method of planting, cleaning, grinding, boiling, and curing the Cane."21 Another influx of knowledgable planters arrived when the English abandoned Suriname, South America after it was captured by the Dutch in 1667 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. About twelve hundred people arrived in Jamaica where "they were well received, and had a large Tract of Land in the Precinct of St. Elizabeth’s, laid out for their Use. In that Part of the Island they settled, and being industrious, soon became considerable."22

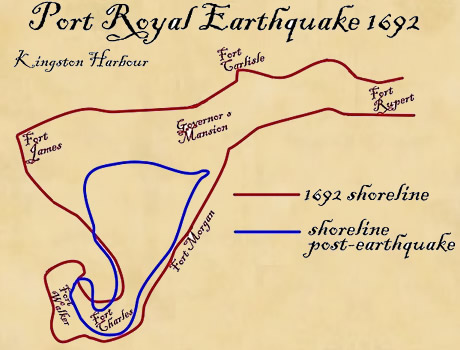

Port Royal continued to to be the hub of trade in Jamaica with the parcels of land being divided

Map of Port Royal Land Mass Before and After 1692 Earthquake

and subdivided to support the merchants, navy, and denizens of the island until the earthquake of 1692, when 33 of the 51 acres of Port Royal were submerged, leaving what was once a peninsula marooned as an island.23 One first-hand account of the wreckage said "that the Water stands so high as the upper Rooms of those [buildings] which are standing. The Earth when it opened and swallowed up People, they rose in other Streets, some in the middle of the Harbour, and yet saved; though at the same time I believe there was lost about 2000 Whites and Blacks."24 As a result of the earthquake, many moved to Kingston while "the principal Merchants removed further up, and began to build; which, by degrees, soon gave the new Settlement the Face of a Town; it as been improved since, to such a Pitch, that it can almost vie with the antient Port-Royal."25 However, the new town was devastated by fire in January 9, 1703, burning all the houses while leaving the forts and most of the ships untouched. This was the final nail in Port Royal's coffin as Jamaica's central trading center; the Jamaican Council voted not to rebuild Port Royal, moving those who had lived there to Kingston.26

Artist: James Hakewill

Spring Garden Estate, St Georges, From A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica (1825)

Another group of experienced planters arrived in 1699, although they were not made as welcome as some of the previous settlers. Some of the Scots who had failed to establish a colony at Darien due to disease and a lack of support from the English government and the East India Company set out in two vessels to find a new Caribbean home. At Jamaica, "although their distresses by famine and sickness were well known, yet the terms of the proclamation [made by Jamaican governor William Beeston at the behest of English Administrator James Vernon] were so rigorous, that they were obliged to gain a lodgement on shore sword in-hand: but they were soon dispersed into various employments, and by their industry acquired in process of time very considerable estates, which are now enjoyed by their worthy dependents."27

1 The Narrative of General Venables, C. H. First, ed., 1900, p. 137; 2 John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 1708, p. 270; 3 Edward Long, The History of Jamaica, Vol 1, 1774, p. 240; 4 Long, p. 243; 5 Long, p. 239; 6 Long, p. 239; 7 Long, p. 248; 8 Long, p. 239; 9 Long, p. 248; 10 Long, p. 245-6; 11 Long, p. 249; 12 Long, p. 257; 13 Long, p. 264; 14 Long, p. 261; 15 Long, p. 268; 16 Long, p. 270; 17 Long, p. 278; 18 Long, p. 300; 19 Charles Leslie, A New History of Jamaica in thirteen Letters, 1741, p. 66; 20 Oldmixon, p. 274-5; 21 Leslie, p. 64; 22 Leslie, p. 112, Oldmixon, p. 281 & Long, p. 296; 23 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 252; 24 Hans Sloane, "A Letter from Hans Sloane", Philosophical Transactions, Vol. 18, Iss. 209, 31 December 1694, p. 84; 25 Leslie, p. 190; 26 Oldmixon, p. 310-1; 27 Long, p. 297

Ships Victualling At and Around Jamaica

There are a couple of examples from the sailor's accounts during the Golden Age of Piracy of ships victualling at Jamaica. The first is Francis Rogers whose merchant vessel the Spy Galley was in Jamaica between August and November of 1705. While there, Rogers goes into some detail about the fish which could be caught there, waxing particularly eloquent about the meat of the green turtle.1

Pirate John Rackham, From A General History of the Pirates (1725)

Pirate John Rackham was around Jamaica at various times where he captured food for his crew. A Jamaican news report dated January 30, 1719 said he was at the island two weeks before when he "carry’d some Provisions from off this Island"2. Rackham's pirates returned in mid-October, 1720 where, among other vessels taken, Dorothy Thomas deposed that her canoe which containing "some Stock

and Provisions, at the North-side of Jamaica, was taken by a Sloop, commanded by one Captain Rackam"3. This trip was to be his undoing; Rackham's crew was caught by Jonathan Barnet near Negril resulting in he and his crew being tried at Jamaica.

Navy sailor John Atkins aboard HMS Weymouth stopped at Jamaica on August 23, 1722 and stayed until January 1st of the next year. Having lived there for so many months, he observed that "Ordinaries [taverns/inns serving a complete meal] are filled with a Mixture of Land and Seafaring People, who have three or four sorts of Cookery at Dinner, and each a Pint of Madeira [wine], with a Desart of Guavas, and other insipid or ill-tasted Fruit. One of our Dishes is frequently Turtle"4. He also mentions that the navy's "Ships Companies [were] being victualled here twice a Week with fresh Beef, during a stay of 6 Months", from the stock of "the Planters having set apart Servants, Pens, and Pasture-Grounds, for rearing up all kinds of Domestick Animals"5.

The last example of victualling at Jamaica from this period comes from apprentice sailor Silas Told, whose merchant ship Prince of Wales arrived at the island in July of 1725. They were on short allowance in the latter part of their trip because it took five times as long as expected. "[W]e arrived at Blue-fields, the west end of Jamaica, without a single pint of water on board, and had been eleven weeks destitute of biscuit, pease, or flour; so that we had neither food to eat, nor water to drink."6 After obtaining water at Bluefields, they sailed to Kingston, where they took on provision and loaded their ship with sugar.

1 Francis Rogers. Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, Bruce S. Ingram, ed., 1936, p. 230; 2 Post Boy, 4-23-19 - 4-25, Issue 4641; 3 "The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and other Pyrates", Piracy in the Golden Age, Vol. 3, Joel Baer, ed., pp. 27; 4 John Atkins, A Voyage to Guinea and Brazil, 1735, p. 243; 5 Atkins, p. 244; 6 Silas Told, An Account of the Life, and Dealings of God with Silas Told &c., 1786, p. 15