Fontanels: Issues and Setons Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Fontanels: Issues and Setons in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Creating a Fontanel: Inserting the Pea Into an Issue

Although most of the hard work of an issue was done by the creation of an appropriately sized wound, the insertion of the pea was a critical part of the procedure, with more of a role than might first be recognized.

The pea's purpose was to serve as an irritant which caused the wound to inflame and generate pus or other serous matter (sometimes called 'gleet'). As explained on the previous page, a variety of objects could be used as an irritant, although the most often used was the dried pea. Pierre Dionis explained

that objects such as dried peas and orris (iris) roots were best because "they imbibe the Humidities of the Cautery, and we take them out always bigger than we put them in, which keeps the Orifice [opening] of the Ulcer, which inclines to contract and fill up [with incarnating flesh] in a just Magnitude."1

Surgeons were concerned about the comfort of the patient, especially when issues were to be left in place for an extended period. Even Richard Wiseman, a fan of issues and setons, explained that when an issue "cannot be kept open with ease to the Patient; it will be requisite that a good Diet be prescribed, and the Humours carried off some other way before you cure the Fistula, and [have] lssues elsewhere opened."2 Although they no period author specifically mentions it their shape, rounded pea-like objects would probably offer the most comfortable irritant to the patient since they would not jab the inside of the wound.

The pea itself could have an important role in creating the issue. Matthias Gottfried Purmann explains that after the wound is opened and ready, "a Pea [is] put into it, with a thin Piece of Silver upon the Pea, and Bolsters [pieces of soft lint] and a Bandage over the Silver Plate, to make the Pea work its way downward; let it continue so for two or three days, and at the next opening you will find the Issue made."3 So the pea actually developed the wound so that it could function as a proper fontanel.

Purmann gives another

An Apothecary at Work, From The Workes of

That Famous Chirurgeon Ambrose Parey (1649)

explanation of the pea's role which provides insight into how the issue could gradually be made. He suggests the surgeon "first put a White Pepper corn for two days, afterwards a Pea to keep it open, and your Work is done."4

Purmann also suggests a recipe for a 'pea' made of medicinals that could be used when the issue stopped ejecting pus.

Rx. Emplastr. Drachyl. Simpl. [Simple Diachylon unguent - composed of oil, litharge of gold (litharge mixed with red lead], root of the Althaea, flax and fenugreek seeds, made into a plaster with the addition of gum ammoniac, galbanum, and sagapenum.] {4 ounces} Ceræ [wax] {5 ounces} Pulv Contharid. [powdered canthrides] {6 drams} Euphorb. [Euphorbium] Agaric. [Agaricum] Ana [of each] {1 dram} Myrrh. {1.5 scruples} Misce f. Massa [mix into a lump] cum s. q. Ol Myrtillorum. [with Oil of Myrtle]5

Note that this recipe contains canthrides, which was discussed in the section on the caustic chemical used to make the fontanel. They were probably key to re-irritating the wound and causing it to generate pus and so 'run' again.

Naturally issues required frequent dressing - they were made to eject foul matter, after all. The whole point of a fontanel was to remove the ejected material on a regular basis and dispose of these poisonous 'humors'. In the case involving a patient with an ulcer, Richard Wiseman explains that he turned the ulcer into an issue by inserting a pea. He then dressed the issue it using "red Sparadrope [sparadrap - an adhesive plaster] and [a] Compress [which] retained it on; then left her to her Mother to dress [the wound], and only called some times when they gave me notice of their wants.”6 In another case, he made an issue in the calf of a woman's leg, which he "kept open by a Pea, [and dressed] with an Emplaster [plaster] and laced Stocking"7. The purpose of the laced stocking was to hold the plaster in place.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 469; 2 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 227; 3 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 22; 4 Purmann, p. 305; 5 Purmann, p. 22; 6 Wiseman, p. 204; 7 Wiseman, p. 49

Creating a Fontanel: Inserting the Seton Needle and Thread

Making a seton was another matter entirely.

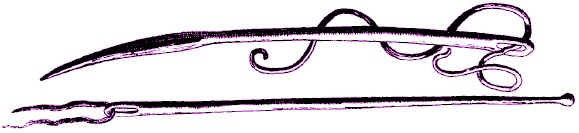

Top: Seton Needle for Piercing Skin, Bottom: Seton Probe Needle, From The

French Chirurgery by Jacques Guillemeau, not paginated (1597)

Here, the seton thread which served as the irritant had to be inserted under the skin by being inserted into one holes and pulled out of another.

This was done using a long needle which could be of two types - one was sharp and pointed, the other was a probe needle with a bulb on the end. The reason for the two different types of needles had to do with the way the two incisions in the skin were made. This resulted in two slightly different procedures for seton insertion.

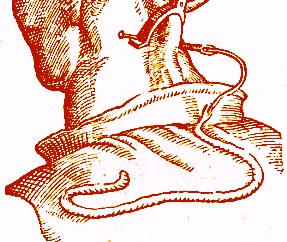

Piercing the Skin with a Seton Needle, From

Armamentarium Chirugicum,

By Johannes Scultetus, Table 34, Wellcome Collection (1741)

The first method used the sharp, pointed needle to make the two incisions in the neck. Matthias Gottfried Purmann explains the procedure.

...having marked the place [where the seton is to be inserted] with the Fore-finger and Thumb of the Left Hand, they [surgeons] squeeze the Skin together, and pluck it up as high as is necessary to sever the Skin from the Muscles. Then they thrust a great three-square Needle with a sharp Point and a little bended, through the fleshy Pannicle, and draw the half Skean of Silk through the Skin, and there leave it1

The second method builds upon the opening of two incisions in the skin by cautery that was discussed previously in Creating a Fontanel: Opening a Wound with Cautery. You will recall that seton forceps with two holes in the flat tongs were used to pinch the skin so that a red hot, spike-shaped cautery iron could be thrust through the skin where the holes were located on the seton forceps. Once the holes were made by cautery, the seton forceps were left in place (clamped together, if they had a locking mechanism) and the probe needle was fed through the newly made holes to draw the seton thread through the incisions.

Making a Seton With Cauterized Wound and Seton Clamps, From The Chyrurgeons Storehouse. By Johannes Scultetus, p. 80 (1653) |

Once the seton thread is in place, John Atkins recommends that it be "dawbed well with Digestive [a medicine to promote healthy flesh formation]."2 In a similar way, Purmann advises the thread be "moistened with a Digestive or Oyl of Roses [an oil believed to prevent inflammation], which must always be done at every Dressing"3.

Atkins explains that the seton "must be cleaned and dressed every Day, by shifting the Skein armed [with medicine] as before"4. Purmann notes that "twice or thrice a day they [the surgeons] draw the Silk from one side to the other, and the Business is done"5. (Purmann's direction to 'draw the Silk from one side to the other' is a bit vague, sounding as if it could either be pulled in one direction or pulled back and forth. Fortunately, this is better explained by another author.)

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis explains the reason for employing digestives and an anti-inflammatory on the thread. "The Seton [thread] is of great use to carry the Remedy all along the Wound, and ought to be very long... [because] the Chirurgeon cuts off that which came out of the Wound, and brought the Matter and Pus with it."6

Artist: Marcus Severinus

Seton Needle Insertion in Neck , From Opera

quae extant omnia, by William Fabry (1682)

Thus, even with the medicine on it, the piece of the seton thread inside the wound would still irritate the skin and cause the formation of pus. Pulling the seton thread out would [at least theoretically] draw the infection out with it. This means that the thread would have to be pulled in the same direction every day.

Another possible benefit of medicating the seton before movement is that much of the medicine would wind up on the first incision hole, keeping it from becoming infected. Infection of the two holes would make moving the seton painful and could eventually compromise the integrity of the two incisions in long-term setons. Unfortunately the second hole would wind up receiving the majority of the infected matter, so it would either have to be well cleaned and medicated after pulling the seton thread through if the surgeon wanted to avoid this.

While Dionis advises that the thread 'ought to be very long', most of the period images do not show it being more than a few feet long at most. There is a practical explanation for this; a thread that was too long would also run the risk of getting tangled in things if it were loose. It seems likely that the thread would be either bandaged or tucked into the wearer's hat, wig, collar or coif.

Since setons could be left in for extended periods of time, the seton thread clearly required changing occasionally. The ever thorough Dionis explains how this was done. "When all the Seton is used, and ‘tis requisite to use more, it must not be run thro’ with the Needle again, but fastened to the end of that which has been drawn thro’. It should be observed, that the Seton must enter at the upper part of the Wound, and come out below at that end where the issue of the Sore is.”7

As has been indicated, setons required frequent dressing, daily at least. For such dressings, Atkins suggested "a Pledgit [small piece of soft lint] of the same [type] on each Aperture [the two holes in the skin], a soft Compress and retentive Bandage"8. Purmann doesn't go into quite so much detail, explaining that surgeons simply dressed setons "with Plaisters and Bolsters, as they do an Issue, as long as they desire to continue the Seton."9

1 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 23; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 180; 3 Purmann, p. 23; 4 Atkins, p. 180; 5 Purmann, p. 23; 6,7 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 21; 8 Atkins, p. 180; 9 Purmann, p. 23

Creating a Fontanel: The Skull

Fontanels - or, more specifically here, issues - placed in the skull required a special procedure. Most issues make use of the skin in which they reside to generate 'laudable' pus. The skin on the skull is quite thin, however, and special measures were required to put an issue there. (It would be difficult to place a seton here because of the shape of the skull and the delicacy required in the operation.)

German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann explains the process. He begins by giving explicit instructions on where to put the issue, because he felt that the "only Difficulty in making an Issue in the Head, is in making choice of a proper Place, for otherwise it will signifie very little."1 In fact, he considers this so important, he provides the reader with three different methods for finding the location.

Location of a Fontanel in the Head, From Armamentarium Chirugicum,

By Johannes Scultetus, Table 34, From Wellcome Collection (1656)

(Yes, you just saw this on the previous page. It's so good here it is again!)

First, take off the Hair about the breadth of a Crown-piece, from the Crown of the Head to the place where the Satura Coronalis and Sutura Sagittales meet; and having found it by feeling about with your Finger, make your Issue there; but if you cannot find it by this Method, and the proper place being all in all, then take a strong Thread, draw it from the tip of the Nose to the hinder part of the Neck, then take another Thread and draw it over the Head in a strait Line, from the middle of one Ear to the other; mark the place where the Threads cross one another, and you have found the Place where you ought to make the Fontanel. Others find the Place after this manner. Let the Patient lay the Joint of his Hand upon the hollow part betwixt the Nose and the Forehead, and extending it to his Head, where the end of the middle Finger touches, is the proper Place to set the Issue.2

Richard Wiseman also gives instructions for finding this location which are very similar to Purmann's second method, lending credence to it. "The way of finding them is, by

passing one String from Ear to Ear, and another from Nose to the Crown of the head. The former of these will shew you the Coronal Sutures, the second the Sagittal, which usually begins at that point where these Lines intersect, being the part where we make the Fontanels"3.

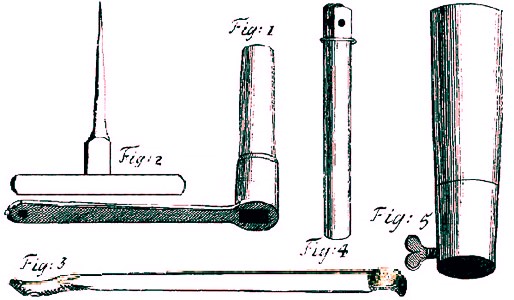

The cutting pipe was to be placed on the cornanel suture (a natural suture in the skull, extending across the skull, roughly from one temple to the other). Then,

Fistula Cutting Pipe and Accompanying Tools for Making Issues in the Scalp, From Chirurgia

Curiousa by Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Table 1 (1706)

holding it with your Left Hand, strike upon it with your Right with such a force, that it may enter into the Cranium: Which being done, take the sharp-pointed Instrument described Fig. 2. and with it thrust forcibly through the Pipe into the Skull, then turn it round, Pipe and all, till you have cut through the Pericranium; then take it out... the Cutting Pipe you must [then] push round from one side to the other, till the Flesh and Pericranium is sufficiently loosened. Then take out the Pipe and the flesh Substance with it, with the help of that Spoon-like Incision knife described in Fig. 3 This being done, put the Pipe in again, and the Iron Instrument described Fig. 4 being first fitted to the Pipe, and made Red hot, with a small Hole in the top, and something longer than the Pipe, that the Screw-pin may go through the Hole (and be fastened to the Handle which is made of Brass, and described Fig 5.) which must be thrust into the Pipe upon the Cranium, and held there till it has burnt through the first Table, and then your Work is done, only the Wound must be dress’d with Unguentum Populeum [an unguent made of the dried leaves of poppies, belladonna, henbane, black nightshade, and poplar buds], with a Pea put into it, and managed like other Issues.4

It is notable that Purmann's procedure for making an issue in the skull requires cauterization to burn through the first (or outer) table of the skull. Once this is complete, he inserts a pea into the burnt hole as an irritant, although this may not have been necessary. While discussing the ancient practice of burning the skull to create an issue, John Kirkup explains, "If the burn mortified the outer table of the skull, dead bone could act as a foreign body sequestrum [meaning the dead bone would basically serve the same purpose as the pea] to provoke a long period of discharge."5

1 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 21; 2 Purmann, p. 21-2; 3 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 437-8; 4 Purmann, p. 3-4; 5 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 402-3

Managing a Fontanel: Dressing Yourself

The bandages and dressings used on issues and fontanels are discussed in detail in the previous two sections, but author Charles Gabriel Le Clerc's 1701 book A Description of Bandages and Dressings talks about a making an issue which could be conveniently managed and dressed by the patient without help, using a fontanel in the arm or leg.

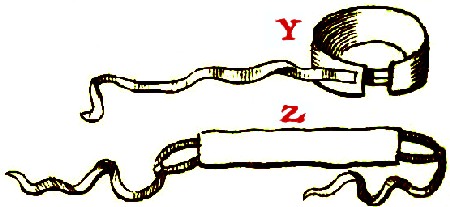

Seton Self Bandages, Cours d'Operations, By Pierre Dionis, p. 578

(1708)

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis thought the idea was worthy of merit, explaining that these dressings were "generally applied to the Arms or Legs, that the Patient may dress them himself, and to that end we make small Bands shap’d like Stirrups Y, Z, which are very convenient for the Arms and Legs"1.

Le Clerc has an idea similar to Dionis'. His explanation is detailed and fairly easy to follow, so it is quoted here in full with the drawing from the text. (Le Clerc usually shows the bandages in his procedures tied together with a string for some reason.)

Self Bandaging Elements, from Charles Gabriel

Le Clerc's A Description of Bandages and

Dressings (1701)

An Issue is an Ulcer in the Skin, made by Causticks applied on it.

1. An Emplaister [plaster] laid over the Caustick [chemical], to keep it on the Part.

2. A Compress in several Doubles [folded in half several times] to be laid over the Emplaister, which must be larger than the Emplaster.

3. A Roller [Bandage] of two Inches broad and an Ell in length [a ell is about the length of a man's arm from the elbow], for keeping the Caustick [chemical] close to the Part.

4. A Pea or small Ball of Orris [Iris] Root to be put in the hole, made by the Caustick [chemical], to keep the Ulcer open.

5. An Ivy Leaf laid over the Pea, to cool the Part, in the room [form?] of an Emplaster.

6. A Compress of Rags in several Doubles, to be laid over the Leaf or Emplaster.

7. A Bandage with which the Patient may dress himself: This is a piece of Linnen-Cloth about three Inches broad, and long enough to go round the Arm; it must have three holes as those marked A A A at one end, and three Ribbons at the other end, as B B B. Apply the middle of this Bandage on the Issue, pass the three Ribbons thro’ the three holes: It is best to begin with that in the middle, and after to tye the other two Ribbons close about the Arm, or Leg.2

Le Clerc adds a note of warning to his description of self-bandaging issues, explaining that this "is not proper for the Nape of the Neck, which is a usual Place, to make Issues in the Distempers of the Eyes."3

He explains that in such a case the patient must use "a Roller with two Heads, of an Inch and a half broad, and two Ells in length; applied on the middle of this on the Issue, and turn its two ends, to-wit, one of each side, quite round the Head, passing a little above the Forehead; then pass a second time over the Wound, and reascend, making diverse rounds about the Part, and round the Head. The Periwig in Men, and the Coif in Women, hides all this Bandage, but a good sticking Emplaister, made of Mastick [mastic - mastic tree resin], may serve turn without all this trouble."4

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 469; 2 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, A Description of Bandages and Dressings, London, 1701, p. 35-6; ,3,4 Le Clerc,p. 36

Managing a Fontanel: Time Left In Place

“…by the sixteenth century the practice of perpetuating an issue indefinitely by this [the insertion of a foreign body into a wound] was common practice.” (John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 403)

It has been noted that fontanels could be used for an extended period of time in this article. Military surgeon Richard Wiseman explains in several of his case studies that patients whose medical problems were treated and cured with the help fontanels still had them in place as of his writing his book, which was probably years or even decades later.1

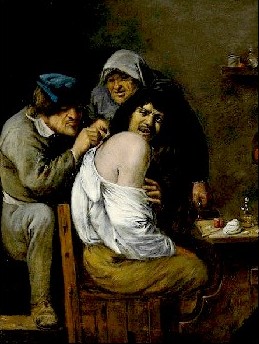

Artist: Joos van Craesbeeck

Doctor Treating a Patient's Issue (mid 17th c.)

Ambroise Paré similarly tells of a nearly blind goldsmith whose sight was "perfectly recovered" through the use of a seton in his neck. He ends the case study noting, "Whereby recovering his former soundness and perfection of sight, he yet wears the Seton."2

The meticulous French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis provides the most detailed information on how long fontanels were to be left in place. With regard to specific wounds, he counsels his students,

The Time which Setons ought to remain in Wounds cannot be positively prescrib’d, but depends on the Chirurgeon’s decision, pursuant to the condition in which he finds the Wound: Some keep them longer in to purge and cleanse the Wound than others, and they ought not to be drawn so soon out of a Gun-shot Wound, as out of one which happens by the Point of a Sword; but Care ought to be taken that they be not left in too long, for that will render the Part Fistulous [riddled with hollow sections] and Callous [covered with hardened skin].3

From this, it sounds as if Dionis does not recommend leaving a fontanel in for a long period. However, in the same discussion he notes that "Cases continually occur when we cannot dispense with the use of them."4 In addition, he advises that "when a person is past forty Years, he ought to keep it [an issue] open for the rest of his Life, if he would not run the risque of falling into some grievous Distemper, which this Humour that ran through the Issue may in time cause."5

Dionis also explains how to heal a seton if it was not to be left in long-term, which is worth mentioning here. "The Wound being cleansed, the Seton is drawn out, and then it heals perfectly well.”6 OK, maybe that wasn't worth mentioning here. However, since all fontanels were basically managed wounds, they could usually be easily healed using regular procedures.

1 For examples, see Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 39 & 49; 2 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 292; 3,4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 21; 5 Dionis, p. 469-70; 6 Dionis, p. 21