Fontanels: Issues and Setons Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Fontanels: Issues and Setons in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Fontanel Use and Humor Theory

Artist: Jakob Suckale - Balancing the Four Humors

"Issues are made ...in all manner of copious Defluxions of Humours to what part soever; for tho’ they do not always free the Patient from his Distemper, yet they give some ease, by carrying of a great Mass of Acrid and Acid Humours." (Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 305)

Most medicinal practitioners during the golden age of piracy held that the body contained four bodily fluids called humors. These included black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood. When a person was ill, it was thought that their humors were either out of balance or had been corrupted, causing them to work against the patient's health. Fontanels were one way to collect and focus the unwanted humors and remove them from the body.

Humor balance was maintained by a variety of methods including bloodletting, cupping and purging using emetics and enemas. Fontanels were focused more on removing corrupted humors than balancing unbalanced humors. Humors were believed to be corrupted in a variety of ways - surplus humors with no useful purpose would degenerate, long-term illness would create them or when damage to the body would cause the creation of harmful humors.

Military surgeon James Cooke explained that a seton was useful because it "derives and intercepts that which flows to the parts of the Mouth and Breast; and that which distils by the spinal Marrow to the Joynts."1 While he doesn't call them by name, his 'flows' refer to bodily humors. He further explained, "The divers Juices are drawn out by Cauteries [used to create issues], Vesicatories [blistering agents], and Fontanels."2

Although his work was not quite as clearly interpreted, the concept is more directly outlined by Jacques Guillemeau.

Jacques Guillemeau

That which in our body is ingendred, can come through any sharpe, corrodent, or bitinge humors, wherthroughe the skinne is corroded, bitten throughe, & exulecerated, of which ulceratione, may be effected & made a Cautery, or fontanelle, which may be called actuall Cauterye.

Heere of we may conjecture and suppose, that the Cautereyes, & fontanelles, weare invented, following nature therin, ther throughe to give passage, to that which is contrary, & opposite unto her3

Another example of this concept appears in French surgeon Ambroise Paré's explained of treating a man with epilepsy. Paré explains that "the Ichorous humours, [which were] the feeders of this disease, being by this means [a seton in the back of the neck, were] ...most probably drawn away and evacuated.”4

English military surgeon Richard Wiseman likewise explained how a patient who had been "labouring under sharp Humours, was ordered [to have] a Fontanel in her Thigh; which a Chirurgeon made and fitted with an Orange-Pea [orange pip or seed]. It grew very painful; but the Patient, supposing it should be so, endured it so long till she could not stand with it"5. Wiseman applied medicines to the troublesome wound being used as a fontanel and healed the ulcer. Once this was completed to his satisfaction, he "made her [another] one in her Arm."6 Clearly the work of the fontanel in removing the 'sharp' humors was too important to have her go without one!

1 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiae, 1704, p. 142; 2 Cooke, p. 389; 3 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 39-40; 4 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 292; 6 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 176

Fontanel Use and Humor Theory: 'Laudable' Pus

From the humoral point-of-view, a fontanel worked via the insertion of a foreign object to act as a counter-irritant in the flesh and create an infection. For a seton, the counter-irritant was a thread or string; for an issue, it was usually a small rounded object such as a pea, seed or similar item. The infection would generate pus, which had been called 'laudable' by various authors since the time of the revered ancient physicians because it was "regarded as a release of harmful humors."1

Artist: David Ryckaert - At The Village Barber Surgeon's (17th c.)

The concept of 'laudable' pus finds its origin in a misunderstanding by a physician author in the 6th century A.D. David Mackenzie notes that Aetis of Amida confused the writings of Hippocrates and Galen. They discussed two kinds of wounds - dry/clean and dirty wounds, noting that the dirty wounds required draining before healing could take place. Aetis misunderstood this and stated that in "all wounds the poison should be removed and that pus was a necessary process of healing."2

Based on this idea, Rogerius (a 12th century Salerno physician) established "the theory of laudable pus as an inviolate rule of wound healing. His advocacy of strips of bacon as drains [in wounds - to allow the egress of infection] fitted conveniently into this theory. He introduced the seton as a counter-irritant or as a drain"3.

This concept continued to be referred to in the golden age of piracy. For example, near the end of his explanation of healing a man with a bullet wound which had shattered his humerus, sea surgeon John Moyle mentioned that after the bone had scaled [cast off the dead bone] "the Fettid Sanies [serum, blood and/or pus, discharged by wounds] became Inoffensive and Laudible Matter [Pus] appeared."4 Fellow sea surgeon John Woodall likewise advised his readers to treat large wounds to produce "convenient digestive medicines to produce laudable quitture [discharges]"5.

As a result, fontanels were used during this era to generate such desired 'laudable' pus.

1 Joan Druett, Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail, p. 22; 2 David Mackenzie, "The History of Sutures", Medical History, April 1973, p. 161; 3 Mackenzie, p. 162; 4 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, p. 55; 5 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 131

Fontanel Use and Humor Theory: Body Types

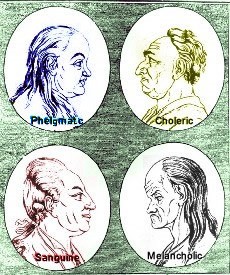

A facet of humor theory suggests four human body types or temperaments. Each temperament is associated with one of the four bodily humors, with the idea that a person with a particular temperament would have more of that bodily humor which impacted their appearance and health. The four temperaments and their corresponding bodily humors were: phlegmatic - phlegm, choleric - yellow bile, sanguine - blood, and melancholic - black bile. Certain temperaments were suggested to be more likely to require fontanels for humor balance.

The Four Humoral Temperaments, From

Physiognomische Fagmente,

by JC Lavaters (1792)

Richard Wiseman mentions this in several places in his book Eight Chirurgicall Treatises. For example, when discussing fistulas-in-ano (fistulas of the anus), he suggests that when they are "the effect of a Cacochymical habit of body [a temperament lacking in blood], especially if the Lungs be weak, or any other of the Viscera [organs of the body], it Will be reasonable to keep it [the fistula-in-ano] open as a Fontanel for discharge of that peccant [corrupted] Matter; but if it cannot be kept open with ease to the Patient; it will be requisite that a good Diet be prescribed, and the Humours carried off some other way before you cure the Fistula, and lssues elsewhere opened."1

Wiseman makes this even more explicit in another passage discussing wounds to the head, noting that when

there be Plethora [excess of blood in the body] or Cacochymia ...in such Habits of body Humours are more apt to stir up ill Symptoms. Therefore you ought timely to let them blood in the Neck or Arm on the same side; and repeat Bleeding according to the exigency [need], and the strength of the Patient’s body. Also Cupping (with or without Scarification [placing cupping glasses over skin with incisions to draw out blood]) of the Neck and Shoulders, with Fontanels under the Ears, is necessary.2

Artist: Johann David Nessenthaler - Melancholy Humor (1750)

Naval physician Hugh Ryder also noted the connection between lack of blood and issues, advising when treating an abscess that a patient of a "Cachochymick Body" habit keep the abscess open using "little pieces of Sponge dipt in an Emplastick [sticking plaster] matter, which I prepared for him, for purpose to keep it open as a Fontanel, which he did for many Months"3.

Some people were considered 'scorbutic', a term suggesting here that they had an excess of black bile - the melancholic temperament. Wiseman discusses the case of a maid with "a scorbutick Habit of body, [who] had an Issue made in her left Arm, which was continued running many years but at length, whether through negligence, or from some other reason, she suffered it to dry up."4 Wiseman indicates here that those inclined towards an excess of black bile would benefit from a long-running fontanel.

He mentions another case of a woman who was "extreme fat, and of a Scorbutick Habit of body, [who] sent for a Chirurgeon to make her a Fontanel in her Arm."5 Although he does not clearly make the link between the habit of body and the fontanel, no reason is indicated in the text for the woman wanting such a treatment other than her temperament.

1 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 223; 2 Wiseman, p. 384; 3 Hugh Ryder, New Practical Observations in Surgery Containing Divers Remarkable Cases and Cures, p. 37-8; 4 Wiseman, p. 176; 5 Wiseman, p. 448

Fontanel Use and Humor Theory: Problems With Fontanels

“It [a seton] is a very terrible and troublesome thing to be tormented with it, especially to tender Persons, but since it is no longer continued than there is urgent Necessity for it, and that in many Cases it’s highly beneficial, several Persons are contented to endure it, in hopes that a Cure will recompence the Molestation.” (Mathias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 23)

Artist: Eduoard Hamman

Ambroise Paré Dressing the Wounded During the Siege of Turin

Because fontanels were based upon an millennia old misunderstanding and they caused infection on purpose, they caused health problems that even the most ardent promoters of counterirritation were unable to avoid discussing.

While explaining his famous discovery at the Siege of Turin that bullet wounds were not intrinsically poisonous French military surgeon Ambroise Paré said that for the patient's first dressing, other surgeons treated them by application of "oyle the hottest that was possible into the wounds, with tents [folded absorbent material, often medicated to keep a wound open] and setons; insomuch that I tooke courage to doe as they did."1 However, he ran out of oil, so he decided to apply medicines made of egg yolks, oil of roses and turpentine to the wounds instead.

Paré returned anxiously the next morning, expecting to find the men treated with the simple medicine in bad straits, but instead found they had experienced "little paine, and their wounds [were] without inflammation or tumor, having rested reasonable well in the night" while the other men were "feverish, with great paine and tumour about the edges of their wounds."2 Based on this experience, Paré switched to using his medicine rather than boiling oil as a treatment of bullet wounds, presumably leaving tents and setons behind as well.

Even more telling are some of the cases discussed by English military surgeon Richard Wiseman in he late

17th century. Wiseman was an advocate of setons and issues, mentioning them in dozens of cases and the

Artist: After David Teniers the Younger

Surgeon Examining Infected Wound On a Man's Foot, From the

Wellcome Museum Collection

treatment of a wide variety of medical problems in his writing. However, he also admits that from the "malign quality of the Humours within our Bodies Mortifications frequently arise; insomuch that we can scarce make a Fontanel in some Bodies without running the hazzard of a Gangrene: nor indeed can they be kept from Defluxion [discharge] after they are made, without the assistance of our Art."3 So, while he admits fontanels can cause problems, he also notes that such problems can be dealt with by the surgeon.

Still, Wiseman details problems with fontanels in several of his case studies. A woman with an issue in her arm came to him when the surgeon who made it told her it was gangrenous. Wiseman reported, "The impression of the Pea [used as an irritant in the fontanel] into the Fat [of her arm] before it was digested [softened in preparation for the formation of pus] had corrupted that, and the Parts about were thereby infected."4 Wiseman scarified the wound and medicated it with turpentine, mercury precipitate and mithridate, which helped heal the wound.

He likewise reports on a lad for whom he made a fontanel in his left arm with a pea in it. This caused an acute, infected rash (or Erysipelas) "from the Shoulder to the Wrist, here and there

Surgeon Richard Wiseman

blistered."5 Wiseman again used mercury precipitate along with basilicon unguent, milk and Galen's recipe for cold cream, which eventually cured it.

Another case involved a patient whose arm was "shining with a burning heat of a citron colour from the Fontanel downward, but upward to the Shoulder it was more red."6 Wise man argues that the fontanel was not to blame in this case, "there being nothing more ordinary than such discharges upon Fontanels: and it was well for him that it there disburthen'd [unburdened] it self". Nevertheless, he medicated the wound, "and put a lesser Pea into the Fontanel with a Pledgit [medicated piece of soft lint]"7. When the inflammation was gone, Wiseman put a large pea back in, which satisfied the patient, although "the Erysipelas spread to that Scapula and Clavicle, and so down to his Breast and Back."8

Wiseman reports on several other 'inflamed' and 'distempered' fontanels, usually treating them by putting in smaller irritants and applying unguents, plasters and 'lenients' (soothing medicines), which solved the immediate problems.9 However, the fact still remains that he encountered a variety of infections caused by fontanels.

In the period following the golden age of piracy, fontanels gradually lost favor with medical professionals. Writing in 1750 about the use of fontanels in epilepsy, head-aches and similar problems, Lorenz Heister explained that "Setons are usually attended with such Uneasiness and Trouble, [that] their good Effects are but seldom experienced by Patients"10. Concurrent with a decline in humors in medicine, John Kirkup reported, “In 1878, [Robert] Druitt [writer of Surgeon's Vade-Mecum] reported issues were rarely used by then, due to their liability to unrestrained infection. In addition they were very unpleasant for patients, who also became malodorous [unpleasant smelling] to others. Moreover, therapeutic efficacy was unproven."11

1,2 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 23; 3,4 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 448; 5,6 Wiseman, p. 38; 7,8 Wiseman, p. 39; 9 For examples, see Wiseman, p. 45 and 47; 10 Lorenz Heister, ,Institutions of Surgery, Part the Seond, Sect. 3, p. 11; 11 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 403 ;