Fontanels: Issues and Setons Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Fontanels: Issues and Setons in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 3

Surgical Tools for Fontanels

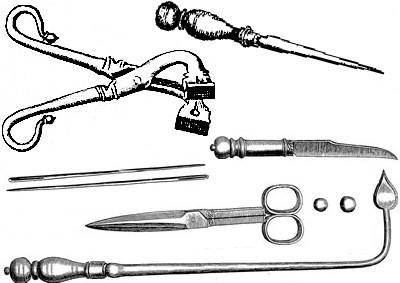

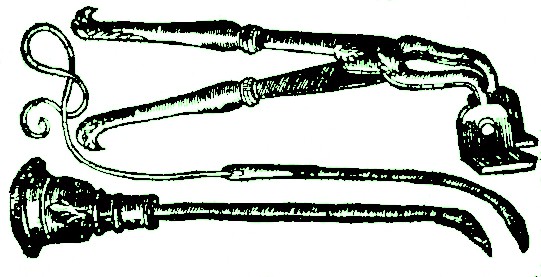

A variety of instruments were used to create fontanels. The first part of the operation required the creation

Tools That Could Be Used to Make Fontanels, From the surgions mate

by John

Woodall. From his instrument Insert & page 211 (1639)

of a wound which could be done in a variety of ways. Most surgeons mention the use of cautery irons to create the wound. Several also discuss the use of caustic chemicals, which was often considered a more 'humane' way to burn holes in the skin than red hot irons. Some surgeons suggest cutting or pinching the wound open with a blade, forceps or scissors.

Once the incision was made, the tool required next depended on whether an issue or seton was to be created.

For an issue, only an irritant was required. This was often a pea or another, similarly-shaped object.

For setons, the tools required were a bit more complex. A needle was needed to draw the irritant - the thread or seton - through. A special tool called a seton forceps (seen second from the top in the image above) was often used to allow the surgeon to hold the skin taut while the cautery iron or seton needle to was poked through the skin. Let's look at each of these tools.

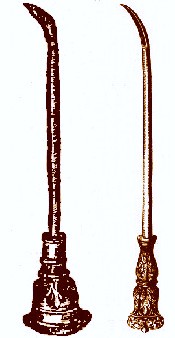

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: Cauterizing Irons

The most frequently mentioned way of creating the wound for a fontanel was by cautery iron.

Cautery Shown For Making Setons, From A profitable and necessarie booke, 3rd ed.,

by

William Clowes, p. 142 (1637)

English military surgeon Richard Wiseman recommended them, explaining that when a surgeon is creating a fontanel, "an actual Cautery answers all Intentions"1.

Jacques Guillemeau waxes eloquent on the use of actual cauteries, explaining that they were more convenient than potential cauteries [caustic medicine which will be discussed in the next section].

Cautery Irons Used to Make Setons

L: Ambroise Paré; R: Guillemeau

[F]or the fyer, is a simple element... the operatione therof is festinous [speedy], certayne, & heathfull, pearcing deeper therin when we please without causing anye accidentes in the circumjacent partes... It is an enimye unto all corruption, wherfor, it freethe alsoe [a wound] from all corruptione, & putrefactione, yea it consumeth all venoumouse matter, & quallityes, which in that parte might lye occulted [concealed], and hidden, consumeth also all superfluouse humidityes [unwanted fluids], and correcteth alsoe all untemperate coulde , and moysture. [Coldness and moisture refer here to a trait assigned to one of the bodily humors - heat is a feature of blood and yellow bile, cold is associated with phlegm and black bile, dryness with black and yellow bile and moisture with blood and phlegm.]2

Guillemeau explained in the introductory pages of his book The French Chirurgery that the surgeon should use "a trianglede Cauterye, to apply therwith a Seton, which both piercethe, & cuttethe... wherewith the skinne of the Necke is apprehendede, for the Seton to passe throughe."3 Here the cautery is being used to create the hole in the skin in preparation for inserting a seton needle. He provides an

Jacques Guillemeau

excellent drawing of his recommended instrument, which closely parallels that figured in Ambroise Paré's instrument drawings for setons. (Guillemeau was one of Paré's students and translated Paré's work from its original Latin.)

Sea surgeon John Woodall comments that cautery irons "are good to make a funtanell or Issue in the hinder part of the head, or in the necke; or elsewhere in the cure of the Lethargie or Apoplexie [unconsiousness], if upon learned & good advice there be held just cause so to do."4 Fellow sea surgeon John Moyle doesn't go into any detail, but he includes a "Seton Iron" in his list of tools required by a sea surgeon.5

German military surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann noted that "in Italy and France they commonly use Actual Cauteries, which are Irons made with a small round Head in Form of an Acorn, which being made very hot, and the Skin touched with it, where you design to make the Fontanel, it will raise a Blister"6. However, Purmann is not actually in favor of cauteries to make fontanels. He elsewhere explains that cauteries used for this purpose "are tedious, painful and dangerous."7 He also warns the surgeon when "burning with a hot Iron, remember not to press the Instrument too deep, for fear it should burn too far into the Flesh and perhaps touch the Pericranium [periosteum - the tough membrane that covers and protects the bones], which would give you a great deal of unnecessary Trouble and Vexation."8

So, cautery iron use was not unanimously supported for making fontanels in the skin. Even Woodall grudgingly admits that the "use of them in many cures is now forborne by reason the terror thereof to the Patient is great"9.

1 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 45; 2 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 42; 3 Guillemeau, not paginated; 4 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 10; 5 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 22; 6 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 22; 7 Purmann, p. 305; 8 Purmann, p. 22; 9 Woodall, p. 10

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: Caustic Chemicals

The second most widely discussed method for making a hole in the skin for fontanels was caustic chemicals or "potential cauteries". Matthias Gottfried Purmann explained that potential cauteries were employed widely in Germany, where they were used "because they are not so frightful to the Patient as burning with a hot Iron."1 French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis recommends using a caustic stones which were solidified forms of caustic chemicals which could be placed on the body to burn through the skin.2 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc likewise suggests the hole in the skin be "made by the Caustick"3.

Photo: Wiki User Rabbitslayer21 - Topical Silver Nitrate Burns

Caustics included a variety of elements. Purmann recommended to his students "that those which are made of Silver [silver nitrate] and Aqua Fortis [nitric acid], are the best that can be used in this Place. Others made of Antimonie, Spir. Nitre [nitric acid], Butyr Antimonie [antimony tricholoride], Aqua Fortis, and the like, are not to be used in making Issue on the Head, because they are less certain that the other."4

Pharmacopoeia author John Quincy (no, not that one) explained that cantharides (or Spanish fly) "are sometimes managed [used] so as to open Issues"5.

French physician Jacques Guillemeau provides a laundry list of caustic chemicals which can be used as potential cauteries. He explains that some of them "are extreame hott, & [others are] a little gentler, accordinge as their operatione is tardive [slow developing]." Guillemeau's suggestions include: cantharides, lye or lixivium (which he calls 'Tartre'), copper sulfate ('vitriol'), an iron sulfate based caustic ('calcined vitriol'), calcium oxide or caustic lime ('unstiffed lims'), orpiment - a type of arsenic sulfide rock ('Auripigment'), arsenic, sodium hydroxide ('the sublimate'), nitric acid and sulfuric acid ('the Oyle of Vitriolle').6 (For more detail on the qualities of some of the popular potential cauteries, see pages two and three of this article.)

Photo: Wiki User balzius - Sodium Hydroxide Burns

Guillemeau admits that he is not a fan of using caustic chemicals to make fontanels. This may explain why he gives an impression in his listing of them that he does not understand their use very well. He rather disparagingly finishes his explanation of potential cauteries noting that there are "more others, the which we nowadayes, doe seldome use, in such sorte as they are".

Guillemeau goes on to explain that the "actuall Cauterye, is much convie[n]ter, then the Potentiall, whether it be we consider on the nature and substa[n]ce, on the healthfullnes, festinatione [speed of use], and the certayntye, in operation". He also indicates that potential cauteries are venemous and are apt to cause "accidentes in the circumjacent partes... [when] therwith we chaucne to touch them".7

His comments are not without merit. Caustic chemicals could take hours to operate and had a tendency to unintentionally burn areas that were near to where they had been applied.

In fact, the majority of the period surgeons under study at this time agree, coming out against the use of caustics to create fontanel wounds. Purmann recommends using simpler, mechanical methods since, like cautery irons, he feels potential cauteries "are tedious, painful and dangerous."8 Quincy advises that cantharides used to create an issue are "a painful and uncertain way."9 Military surgeon Richard Wiseman suggests that "every young Chirurgeon knows in his make[ing] of Fontanels, that he cannot apply a bit of Caustick [chemical] so little, though he use all his Art in defending it [the area surrounding], but that it will have spread much farther than he designed it."10

1 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 22; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 469; 3 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, A Description of Bandages and Dressings, London, 1701, p. 35; 4 Purmann, p. 22; 5 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, p. 221; 6,7 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 41; 8 Purmann, p. 22; 9 Quincy, p. 221; 10 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 450

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: Cutting Implements

Although cauteries appear to have been the most widely used method for opening wounds in the skin, they weren't the only way to create a fontanel. The surgeon could also cut the skin, using a variety of sharp instruments and, in one case, forceps.

None of

Photo: Mission - The Author's Reproduction Period Scalpel

the period authors specifically mention a scalpel in conjunction with fontanels. Several do discuss the operation of cutting the skin, however, and a scalpel seems to most likely tool for doing this. In one of his case studies, military surgeon Richard Wiseman explains that "a Fontanel was cut in his [the patient's] left Arm, which being digested [softened], the Physician and Chirurgeon were dismissed."1 He also suggests opening an existing wound to be used as a fontanel "by knife", most likely referring to a scalpel.2 Sea surgeon John Atkins likewise explains during the treatment of a patient's head wound,

"I cut him an Issue"3 and in another head wound explains that he "had a Fontanel cut inter Scapulas

Probe Scalpel with Knob on End, From Armementarium Chirurgicum, by Johannes Scultetus, Wellcome Collection (1741)

[between the shoulder blades]."4

A scalpel might also be used to open an existing wound and turn it into a fontanel. In this case, a probe scalpel would probably be used such as is seen in this image - the knob on the end protects the skin in the wound when introducing the blade for cutting the sides.

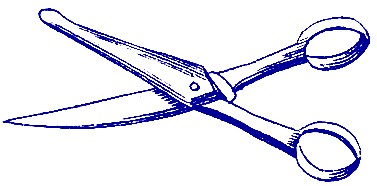

Probe Scissors with Knob on End, From Armementarium Chirurgicum,

by Johannes Scultetus, Wellcome Collection (1741)

Richard Wiseman sometimes used scissors to open the skin. In one fistula-in-ano case, he says he "laid open the Sinus [an existing fistula] with a pair of Probe-scissors to the Anus"5. Like the probe scalpel, probe scissors had a knob or button on the end to allow the scissor blade to enter the orifice without piercing the skin unintentionally.

Wiseman used them in another fistula-in-ano case where "finding much Matter discharged out of it [the fistula] I made a search, and found it run up close along the Rectum, I laid it open to the Anus by a snip with a pair of Probe scissors"6. It should be noted that Wiseman was not using the scissors to create a fistula, but to open an existing wound that terminated in the anus so that it could briefly function as a sort of fistula and heal.

Artist: G. M. Faenisch

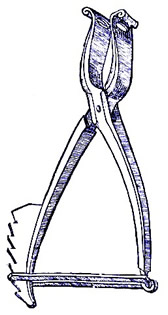

Nasal Polyp Forceps in Use, Wellcome Collection (17th c.)

German military surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann uses surgical scissors in combination with a needle to pierce the skin, raising it with the needle so that the skin can be cut with scissors.7

Purmann discusses some other instruments for opening the skin to create a fontanel. For example, he explains that "Some [surgeons] only use a small Pair of Pincers not unlike those which are used in the Polypus of the Nose, with which they pinch a hole in the Skin, big enough to put a Pea in. This is quickly done, and I have performed it very often with great Satisfaction. However, Care must be taken not to pinch too deep into the Flesh."8

Although he doesn't provide an image of the tool used, the image at left shows the type of pincers which were used in nose polyp surgery at this time.

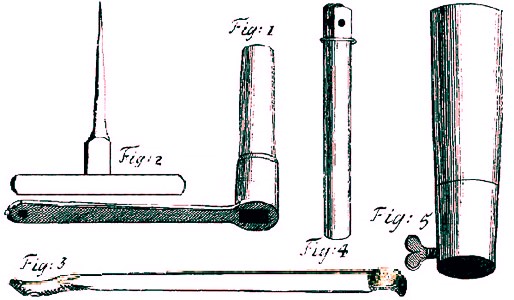

An even more curious set of tools discussed by Purmann are centered around a tool that he calls 'a cutting pipe'. Purmann explains that the cutting pipe is "very useful in making a Fontanel on the Sutura Coronalis, through the first Table of the Skull."

Fistula Cutting Pipe and Accompanying Tools for Making Issues in the Scalp, From Chirurgia

Curiousa by Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Table 1 (1706)

The cutting pipe (Fig: 1), is "made of Case-hardened Steel, turned out of one Piece, big enough in the lower part for a large white Pea to be lodged in it, and about the breadth of three Fingers long, and sharp at the bottom."9

Several other tools are required for this operation including a special, spike-like instrument (Fig: 2) for making a crack in the cranium, a "Spoon-like Incision Knife" (Fig: 3) for removing skin and bone from the cuttting pipe, a cautery iron (Fig: 4) for burning the skull and the handle for the iron (Fig: 5). The process for using these tools is explained will be explained in detail on the following pages.

1 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 38; 2 Richard Wiseman, p. 350; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 92; 4 Atkins, p. 89; 5,6 Wiseman, p. 226; 7 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 305; 8 Purmann,p. 22; 9 Purmann,p. 3

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: The Issue's Pea/Pill

As noted, issues used an irritant in the wound to infect it and cause the formation of 'laudable' pus. For issues, these irritants were usually rounded to provide the least amount of discomfort to the patient. Many authors referred to them as peas, occasionally using the term when they weren't actually using peas at all. (This was probably due to their size and shape and the fact that peas were often used.) Richard Wiseman explains in one case study how he "put [in] an Orange-Pea in the Ulcer and continued it as a Fontanel with much ease."1 Wiseman is here referring to an orange seed. (This is in itself interesting, given that orange seeds sometimes have a sharp end which could irritate the wound.)

Peas and Other Fontanel

Irritants, From Cours

d'Operations by

Pierre

Dionis,

(1708)

Charles Gabriel Le Clerc advises, "A Pea or small Ball of Orris Root to be put in the hole... to keep the Ulcer open."2 French surgical instructor likewise advises the use of a "great Pea Q, or a round Stopple made of Iris-Root R. Some content themselves with cutting in a little waxen Ball S; but the Peas and Iris-Root are better"3. (Isn't his drawing helpful?)

In his book on instruments, historian John Kirkup notes that various period surgeons discuss a variety of foreign objects in an issue. Among them were "a pill of either gold silver, lint, orris root, or other vegetable materials into the burn, protecting this with an issue plaster made of wax, turpentine and red lead."4 Ship's surgeons probably wouldn't use precious metals, given their salaries and the means of their patients. None of the authors under study suggest precious metals as irritants in any case.

Photo: Lucien Mahen - Dried Orris Root

Kirkup goes on to explain, "In Britain, dry peas, beans, or beads were commonly inserted, in France, orange pips [seeds] and portions of iris rhizome ['root'] were available as well; in America the use of peas, corn grains, pebbles, beads, and orris root were recorded."5

You may have noticed that orris and iris roots are repeatedly mentioned by surgical authors. Orris, or iris, roots were a 'powerful Purger of watery Humours' according to apothecary John Quincy. He continues, "Pease [peas] made out of the Root is much in use to dress Issues with, to promote their Running"6. He doesn't list any other properties of the root that would make it useful in an issue, so its drying properties seem to be why it was used. This was likely considered useful for absorbing caustic chemicals and the serosities generated by an issue.

More than one pea could apparently be used as well. When discussing complications in a case study, Wiseman gives a case study where a woman had "a Fontanel in her left Arm; which she had kept for the space of eight years; but now, not being able to ease her self by the usual method, she threw out the two Pease and endeavoured to cure it: but it became more painful, and would not heal."7

1 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 176; 2 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, A Description of Bandages and Dressings, London, 1701, p. 35; 3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 469; 4,5 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 403; 6 John Quincy, Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea, p. 120; 7 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 175

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: The Seton Needle

When making a seton, the first element required was a rather large needle - much bigger than that used in suturing.

In his list of instruments required for a surgeon going to sea,

From Top, Seton Needle for Piercing Skin, Triangle Cautery Iron and Seton Probe Needle, From The

French Chirurgery by Jacques Guillemeau, not paginated (1597)

John Moyle includes "large Needles" directly after "Seton Iron" (referring to the cautery iron used for making a fontanel.)1

Jacques Guillemeau shows two types of needles in his book: 1) A piercing seton needle which is used to "transforate [bore through] the skinne without the tenacles, or tonges"2 (above top) and 2) A probe needle which is used fed through the wounds made by a cautery iron (The cautery iron is shown above middle, and the probe need is seen above bottom).

Guillemeau explains that when employing a cautery iron, the surgeon is to use "a trianglede Cauterey, to apply therewith a Seton, which both prickethe, & cuttethe"3. The cautery would be heated and then poked through the skin which was being held taut with seton clamps (these are explained in the next section). Since the wound is already made, a probe needle is used to allow it to enter the incision without tearing the flesh.

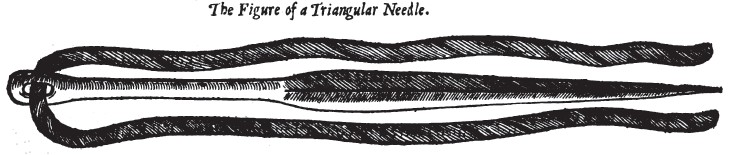

Surgical instrument historian John Kirkup explains that piercing seton needles were like "large lancets with the addition of a proximal eye to convey silk, linen, and other materials through a fold of skin, and thus setons also penetrated to their maximum width."4 This means the body of the needle would have to cut the skin wide enough to allow both the eye and the seton (thread) to pass through the wound. Ambroise Paré shows a Triangular needle in his book which shows such a broad cutting needle.

Ambroise Paré's Triangular Seton Needle, From The Workes of That Famous Chirurgeon Ambrose Parey, p. 293 (1649) |

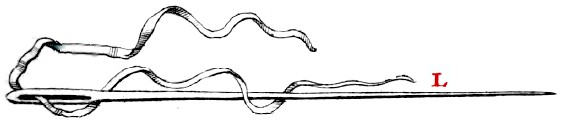

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis describes the seton needle in detail. "To run the Seton thro' the Wound, requires the small Instrument L,

A Seton and Seton Needle, From Cours

d'Operations by Pierre Dionis,

p. 23 (1708)

which we call a Seton Needle: "Tis round, pointed like a Clove of Garlick, that it may not prick the Wound in its Passage; it has a large Eye in the Head, thro' which a Seton is drawn; and 'tis also requisite that it should be very long, in order to run thro' from the beginning to the end of a Wound, which pierces... from one part to the other."5 Curiously, Dionis' description suggests the end is rounded like a probe needle, while his drawing shows it being pointed like a piercing needle.

German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann recommends the use of a piercing seton needle, explaining that this method is easier, causing no more "trouble than pricking with a Pin", which he felt was preferable to cauterizing the wound first, which was slower or more painful.6

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 22; 2,3 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, not paginated p. 24; 4 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 184; 5 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 21; 6 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 305

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: The Seton (Thread)

Although the term 'seton' has been used in this article to refer to the type of fontanel which used a thread as an irritant, the word seton originally referred to the thread itself. The Latin word sēta, from which seton is derived, is defined as "1. A bristle, stiff, shaggy hair of an animal, even of a man, 2. A horse-hair fishing line."1

Sea surgeon John Atkins hearkens to the Latin origins of seton, defining "Setacea.

Seaton, (a Seta,) Hog’s Bristle, or rough Hair, that in the first use of Operation was thrust through the Orifices". He then goes on to list more modern materials used in favor of animal-based setons.

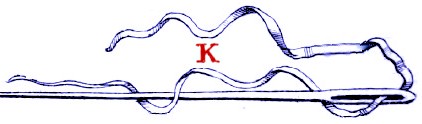

Seton Thread in Needle, From Cours

d'Operations by Pierre Dionis,

(1708)

Frenchman Pierre Dionis' surgeon's textbook explains, "What we call a Seton is a small String run thro' a Wound from its beginning to its end; this String, K, was formerly made of Horse-Hair; but being found to incommode and cut the Wound,

some made use of such Cotton Wicks as are put into Lamps, and others of

Woven Linen Tape

several Hempen Threads joined together; but for my own part, I find

nothing better than narrow Linen Tape, for Linen agrees well with Wounds."3 Linen tape is a flat ribbon of linen material tightly woven on shuttle looms. Based on Dionis' drawing, that used in setons was of a fairly small width.

Silk was also used, even at sea. Sea-surgeon Atkins describes the material he used in created a seton as "a small Skein of Thread or Silk, strung through the Seton Needle"4.

1 Charles Duke Yonge, Phraseological Latin-English Dictionary, Part II, 1856, p. 491; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 180; 3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 21-2; 4 Atkins, p. 180

Surgical Tools for Fontanels: Seton Forceps

Sometime in the fifteenth century an English manuscript shows "seton forceps designed to facilitate the procedure by grasping a fold of

Seton Forceps and Needles, From A Profitable and Necessarie Booke,

by William Clowes, p. 73 (1637)

skin while a cautery or needle penetrated apertures in the jaws."1 Writing in the late 16th century, William Clowes' A Profitable and Necessarie book shows seton forceps with both the piercing needle (which has a pointed, cutting end) and the probe needle (which has a knob on the end). As noted in the discussion of the seton needle, the piercing needle could be used with or without the seton forceps, although the forceps would allow for easier skin penetration if they were available to the surgeon.

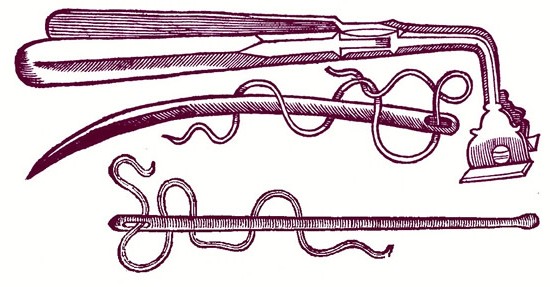

Paré's Seton Forceps, Needle and Cautery Iron, From The Workes of That Famous

Chirurgeon Ambrose Parey, (1649)

Ambroise Paré's book shows the seton clamp with a pointed cautery iron and what appears to be a piercing needle.2 Jacques Guillemeau, Paré's student, explains that seton clamp (which he calls 'tonges') "are pearcede, to thruste there throughe the Seton."3 From this description, he appears to use the seton clamp with a piercing needle, not utilizing a cauterizing iron to make the holes first. However, he later explains that the holes in the seton clamp are there so that "the hott Cauterye, shoulde not chaunce to touche the skinne of the Necke."4

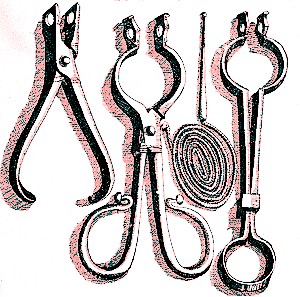

Although the above seton forceps look very similar in design, there were variety of different styles of

Various Seton Forceps Designs with s Probe Needle and Seton

Thread, From Armementarium Chirurgicum,

By Johannes

Scultetus (1657)

seton forceps from the period. German military surgeon Johannes Scultetus shows three different styles of seton forceps in the 1657 edition of his book Armentarium Chirurgicum, seen in the image at right.

Two of these designs are based on standard non-seton forceps designs from the time period. Of interest is the difference in how far the jaws of each can be opened. The first, smaller force was probably used to make setons on the arms and leg because the jaws would only open an inch or two. The second design, with the rounded section above the seton holes was most likely used on the shoulders and neck because it could be opened several inches.

The third design is a spring forceps which would naturally stay open without the square locking piece to hold it closed. The lock enabled the surgeon to set the forceps so that wouldn't move while he was working with the cautery iron. John Kirkup explains that these forceps would be "applied left-handed to facilitate passage of needle and silk by the right hand through the forceps jaws."5

Several other seton forceps designs appear below. The first is similar to that shown in Woodall's tools (seen at the top of this page, although his sketch has a somewhat confusing perspective). These forceps are bent like the crow's bill forceps with a scissor operating mechanism. The last two seton forceps (probably more correctly being called clamps) each have a locking mechanism. The first is a design by William Fabry from the 1682 edition of his book Opera quae extant omnia. It features a pivoting lock on the handle which fits into a rachet on the side to hold it closed. The second is an extant tool from the Wellcome collection that is hinged and has a wing nut and screw locking mechanism.

Crow's Bill Scissor Style Forceps Photo From the Wellcome Collection (17th c.) |

Artist: Marcus Severinus Locking Seton Forceps (1682) |

Locking Seton Clamp, Locking Seton Clamp, From Wellcome (17th-18th c.) |

1 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 403; 2 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 292; ,3,4 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, not paginated p. 24; 5 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 218