Fontanels: Issues and Setons Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 Next>>

Fontanels: Issues and Setons in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Creating a Fontanel

The procedure for making a fontanel seems fairly

Surgical Operation On a Man's Arm, After Adriaen

Brouwer,

From the

Wellcome Collection

simple - you burn a hole in the skin, insert an irritant substance and then bandage it over and wait for it to start ejecting pus and similar serums.

Of course, the devil was in the detail. Several things had to be determined in order to create an effective fontanel. The first decision to be made was where the fontanel was to be placed. A surgeon might even decide to use an existing wound as a fontanel.

If the surgeon was not using an existing wound, the next decision was how the hole in the skin was to be made. It could be done using cautery iron, caustic chemical or cutting implements. Then they had to decide whether the fontanel was to be an issue with a pea (or pea-like) irritant or a seton with a thread-like irritant.

Once the irritant was installed, the wound would be dressed and left to run. Fontanels could be left in for a short period or for several years or more, depending on its purpose. Let's look at each of these ideas in detail.

Creating a Fontanel: Where Placed

“To make a Fontinel or Issue is no considerable piece of Art, but to set it in a proper place is all the Skill." (Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 305)

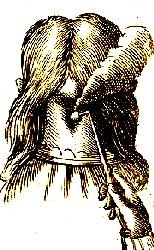

Location of a Seton in the Neck, From A General System of

Surgery,

by Lorenz Heister, Table 21 (1750)

Many fontanels were placed on the back of the neck1. Sea surgeon John Woodall said it was "good to make a funtanell or Issue in the hinder part of the head, or in the necke"2. Setons are often shown being put in the back of the neck in period and near-period illustrations. Sea surgeon John Atkins explains that while setons "may be drawn through any fleshy Part, but [they are] commonly on the Back of the Neck."3 Setons were often placed there when the trouble being addressed was with the head.4

Another location frequently mentioned for fontanel creation was between the shoulder blades or inter scapulas.5 This site was often used for other humoral treatments as well, including cupping and blistering.6

Arms and legs seem to have been fairly popular sites for fontanels; several authors recommend them.7 German military surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann advised,

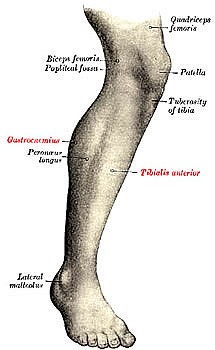

Leg Description, From Gray's Anatomy,

Plate 1240 (1918)

"The Antients made them between two Muscles on the outside of the Arm, or Leg; but now they [surgeons of the 17th century] set them in the inside of the Arm or Leg, between two Muscles; finding by Reason and Experience that they run better there than on the outside."8

Purmann gives further detail on fontanels in the leg as well. "If the Issue is to be made in the Arm, let it be in the Left if the Malady will allow it, for there it’s less troublesome especially to Working People. Let the place be the inside of the Arm, between the Musculus Tibialis [tibialis anterior - located on the outside of the tibia bone in the lower leg, near the shin] and Garstemnemius [gastrocnemius muscle - located on the back of the lower leg]."9 Purmann indicates that fontanels of the leg are usually made in the lower part, noting that, "In some cases they are made above the Knee, but this seldom happens"10.

French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis embraces fontanels in these locations for a specific reason, explaining that when "Fontanels, are made on adult Persons, they are generally applied to the Arms or Legs, that the Patient may dress them himself”11.

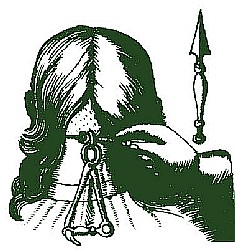

Issues were sometimes made on the top of the head, with devices such as Purmann's

Location of a Fontanel in the Head, From Armamentarium Chirugicum,

By

Johannes Scultetus, Table 34, From Wellcome Collection (1656)

cutting pipe.12 Wiseman advises such issues for blows to the head because "Matter may be unhappily retained, and cause a Caries [decay of the skull], and sooner work through to the Dura mater [membrane surrounding the brain] than in other parts of the Scull."13

Setons could also be placed in the ear for problems of the head. English military surgeon James Cooke advises when setons are placed "[i]n the Ears, 'tis admirable, for pain in the Teeth, and sore Eyes"14. Wiseman explains that famous 17th century physician Sir Francis Prujean "prescribed setons behind the Ears" for Opthalmia (inflammation of the eye) when neck setons became swollen.15

If fontanels could be made on the skull where there was almost no skin, they could be made just about anywhere. After discussing their use in the usual locations, sea surgeon John Woodall explains that fontanels could be placed "elsewhere in the cure of the Lethargie or Apoplexie [unconsciousness], if upon learned & good advice there be held just cause so to do.”16 Jacques Guillemeau likewise suggests that they could be set "in all partes of the bodye, wherone might be applyed, whe[n] onlye the agilitye, or actione of the parte can not ther through be hindered or hurte"17. Guillemeau's only restriction for a fontanel's location is that they aren't set in a place where they cause undue discomfort. Not everyone was so concerned; James Cooke suggested putting a seton "in Scrotum, for Hernia aquosa [a fluid-filled hydrocele in the testicles].18

1 For examples, see Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 22, Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, A Description of Bandages and Dressings, London, 1701, p. 36 & Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 292; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 10; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 180; 1 See Paré, pages 292 & 405 and Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 308 for examples;5 For examples, see Wiseman, p. 40, James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiae, 1704, p. 139, & Atkins,p. 187; 6 For examples, see Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 384, Atkins,p. 187 & Wiseman, Eight Treatises, p. 50; 6 For examples, see Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 39, Le Clerc, p. 35 & Wiseman, Eight Treatises, p. 38; 8,9,10 Purmann, p. 305; 11 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 469; 12 Purmann, p. 3-4; 13 Wiseman, Several Treatises, p. 374; 14 Cooke, p. 142; 15 Wiseman, Eight Treatises, p. 308; 16 Woodall, p. 10; 17 Guillemeau, p. 39; 18 Cooke, p. 142;

Creating a Fontanel: Using An Existing Wound

Fontanels were sometimes created using an existing fistula or wound. Richard Wiseman is the only period surgeon to discuss this method, so it may not have been widely employed. However, he mentions doing so multiple times; so his surgical readers would have been familiar with the idea of making a fontanel from an existing wound. He advised that when fistulas were "the effect of a Cacochymical [corrupted fluid] Habit of body, especially if the Lungs be weak, or any other if the Viscera, it will be reasonable to keep it open as a Fontanel for discharge of peccant Matter"1.

Wiseman mentions using several fistulas-in-ano (a fistula which ended inside the anus) as issues.

Photo: Thomas H.

A Fistula-in-Ano Which Has Been Opened by Incision

(This is just what you were hoping to see today, yes?)

In one case he explained that it was "reasonable to keep it open as a Fontanel for discharge of that peccant [disease causing] Matter"2. He notes

that such fistulas "are not always curable, nor safe to be cured; they frequently serving nature for the discharge of superfluous Humours, brought down by the Haemorrhoidial vessels: so that unless they be painful and vexations in keeping open; you ought not to cure them; especially if they be small and terminate in the circumference of the Anus."3

Wiseman gives detail on how to make an existing fistula-in-ano serve as a fontanel, first advising the surgeon on how to deal with callused wounds.

...if you apprehend that the Orifices of them will swell and not keep open, or that by reason of the contraction of the Callus the Matter may be streightned [tightened], and insinuate it self lower or deeper, and render the evacuation troublesome; you may then apply a small Caustick upon the Orifice to remove the Callus, after which separation of the Slough, the Orifice may be kept open with more ease as a Fontanel; and for the receiving the Matter, and preventing of excoration [scratching the skin open]; the Patient may wear a Pledgit of fine Tow [folded piece of inexpensive linen cloth] which will fit close without Bandage; or it may be spread thin with any lenient [softening] Unguent; as the exigency [need] requires; and be kept clean with out pain or considerable trouble, till time shall cure it; or indicate what to do more in it.4

His explanation clearly suggests that this was a usual and appropriate procedure. He used this method in several other fistula-in-ano cases.5

Wiseman frequently converted existing wounds into fontanels. While treating a man's leg, Wiseman created "a couple of Issues inter Scapulas" which he says helped cure a 'Tubercle in his Ham'

Photo: Amrith Raj - An Abscess

(an outgrowth located on the lower leg)". The wound remained in the leg after removal of the tubercle, so Wiseman "left a Pea in it to keep it open as a Fontanel." However, he later explained that the leg was too infirm from "the great Inflammation it had laboured under" to support the fontanel and he eventually cured it.6

He also advised that when an ulcer was the result of an abcess [pus collected under the skin], the matter was first to be removed by opening the abscess. Once that was done "you may keep it open by Cannula [a hollow tube] or with a Pea threaded, as a Fontanel, till Nature shall be disposed by the Physician's help to heal the internal Viscera [organs], and then the external Ulcer will heal of it self under the Pea, if you leave it not timely out."7 He used similar procedures on ulcers.8

1 Richard Wiseman, Eight Chirurgicall Treatises, 3rd Edition, p. 227; 2,3,4 Wiseman,p. 223; 5 For further examples, see cases in Wiseman, p. 226-8; 6 Wiseman, p. 40; 7 Wiseman, p. 201; 8 For example, see Wiseman, p. 203 & 204

Creating a Fontanel: Opening a Wound with Cautery Irons

Cautery irons were often used

French Surgeon Pierre Dionis

to create the wound(s) required for fontanels. Sea surgeon John Woodall explained that the much revered "ancient Chirurgeons of former ages used these instruments" and that they were particularly good for creating fontanels.1 Although he didn't favor cautery irons in operations, French surgeon Pierre Dionis admitted that the "Cauteries or Issues which some call Fonticles, and the Italians Fontanels, are made on adult Persons”2.

Dionis' statement suggests the words 'cauteries' and 'issues' could be used interchangeably, probably hearkening to the ancient origins of the procedure. French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau says something similar, referring to 'Cautereyes, & fontanelles', which he supposes "weare invented, following nature therin, ther throughe to give passage, to that which is contrary, & opposite unto her, & whereof she is perturbated, & molested"3. The link is definitely made by Guillemenau between cauteries and issues, suggesting that the cauterized wound is similar to the way nature operates.

Cautery irons were used in both types of fontanels: to burn the single hole required for an issue and the pair of holes needed for a seton. The procedure for each type of fontanel was slightly different.

Photo: Mission - Olive Cauteries, From the Author's Collection

For an issue, the surgeon seems to have preferred an

Using an Olive Cautery to Make

An Issue, From L'Arcenal de

Chirurgerie, by Johannes

Scultetus, (1665)

olive cautery which looked like a bulb with a point at the end of it. German surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann notes that when issues were made in Italy and France,

the surgeon used "Irons made with a small round Head in Form of an Acorn, which being made very hot, and the Skin touched with it, where you design to make the Fontanel, it will raise a Blister"4.

The acorn or olive design would allow the surgeon to bore into the skin and leave a wound wide enough to insert the pea.

For setons, the procedure was a bit more complex. During the golden age of piracy, the normal way of creating a seton made use

Cautery Iron Being Inserted in Holes of Forceps

From L'Arcenal de Chirurgerie, by Johannes

Scultetus, (1665)

of cautery forceps to hold the skin while the cautery iron was thrust through the two holes in the forceps. The type of cautery iron often shown for this procedure was thin and spike like5, probably because the holes created in the skin only needed to be large enough to allow the seton thread to be drawn through.

In her book Antique Medical Instruments, modern historian Elizabeth Bennion explains the procedure used to create seton holes using such a cautery iron, quoting William Salmon's 1699 edition of Ars Chirurgica: "Take up the skin with a perforated pair of forceps, nip it pretty hard to stultify [numb] it. Through the perforations [holes] of the forceps and the skin pass the needle red hot"6. So it was actually quite a simple process. The seton forceps would allow the cautery iron to create two incisions at once as it passed through the holes of the grips that were pinching the skin and holding it.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 10; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 469; 3 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, p. 40; 4 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 22; 5 For images of these cautery irons, see the previous page and Guillemeau, 'Diversche Instrumenten Beguame Voor de Ooghen', non paginated section & Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 292; 6 Elizabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments, p. 69

Creating a Fontanel: Opening a Wound with Caustic Chemicals

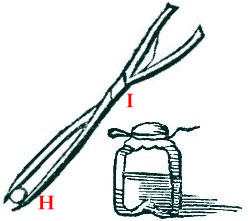

Cautery Pincers I and Stone H with Bottle, From

Cours d'Operation by Pierre Dionis, Table LVI,

page 835 (1740)

As explained in the discussion on the types of caustic chemicals used, most surgeons preferred to avoid them in favor of cautery irons. However, French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis recommended them. He used concreted cautery stones for the procedure rather than raw chemicals because they would have a more concentrated and controllable effect.1

You can see in the image at left that the cautery stone (H, being held by the cautery pincers I) is about the size of the irritant pea that would be inserted into an issue, which would mean the small hole left when the cautery stone was removed would be conducive to the pea.

Dionis provides his usual clear instructions on how this was performed, including a number of helpful sketches of the tools required to perform the operation. However, the details of this process have already been explained in detail on this web page, so I refer you to the relevant page of the Cautery Procedure article for those interested in understanding it.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 468

Creating a Fontanel: Opening a Wound Using Cutting Implements

Pricking the Arm with a Needle,

From

Armamentarum Chirurgiae Appendix,

by Johannes Scultetus, p. 188 (1671)

Cutting instruments were sometimes employed to open the wound for a fontanel, although the period surgeons do not provide us with much information about the process of using them for this purpose. Fortunately, the operation of tools such as scalpels, pincers and scissors in making holes in the skin is fairly straightforward. The procedure for using them to make a wound can be readily understood from the tools seen in the section on Surgical Tools for Fontanels: Cutting Implements on the previous page.

One of the more involved skin incision methods comes from German military surgeon Matthias Gottfried Purmann's book Chirurgia Curiosa. Purmann uses surgical scissors in combination with a needle. "There are several ways of making an Issue; but having marked a place [where the issue will be] and then putting a Needle through the Scarse Skin [easily pierced skin - most likely referring to the epidermis], and cutting it [the skin] off under the Needle with a pair of Scissors, big enough for a Pea to be put into the Orifice thus made."1

While Purmann's explanation is a little confusing, it involves lancing the skin with a needle, holding the needle roughly parallel to the skin to raise it up and then cutting the raised skin with the scissors. 'Under the needle' seems to refer to the skin which is pulled up on either side of the needle. Doing so carefully would create an effective space for the placement of the pea.

1 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiousa, p. 305