Wound Dressings Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Next>>

Wound Dressings in the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

"[1687] Mr. Fitz-Gerald... professed Physick and Surgery, and was highly esteemed among the Spaniards for his supposed Knowledge in those Arts; for being always troubled with sore Shins while he was with us, he kept some Plaisters and Salves by him; and with these he set up upon his bare natural Stock of Knowledge, and his Experience in Kibes [Chapped or inflamed areas on the skin, especially on the heel, due to exposure to cold]." (William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, p. 264)

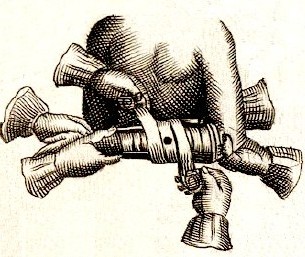

Wrapping an Arm Wound, The Chyrurgeons Storehouse,

by Johannes Scultetus, Table 27,p. 68 (1653)

Today we think nothing of bandages - they are freely available at the local market manufactured with pre-applied stickum, already attached pads with some even being pre-medicated. Any Boy Scout or person with Red Cross First Aid training can explain the proper method for tying an ankle bandage using a piece of cloth. However, a little bit of knowledge in how to dress wounds could be a valuable skill during the late 17th and early 18th centuries

in the rough-and-tumble world of the Caribbean as the informally trained Mr. Fitz-Gerald might have attested.

Medicine was still in its infancy in many ways and the procedures for treating wounds still had a touch of the mystical about them. Each of the pieces of dressing that were required to treat a wound, fracture or dislocation had a name and a history often dating back to the time of Hippocrates or Galen. The ancients' advice was still revered by the surgeons of the golden age of piracy and their methods were often closely followed.

With this in mind, we are going to look at four types of wound dressings that were prevalent at this time. Many of them are still used today, some bearing the same names as they had centuries ago. Others had more arcane titles that have long been lost in the mists of time. Most of the elements of wound dressing will sound at least familiar, although there are a few, like plasters (also called poultices) which have been largely abandoned. We will begin with plaster, then move on to the three wound dressings that are still in use today: pledgets, wound tents and bandages. We'll also look briefly at how these devices were used in some surgical procedures.

Plasters (Poultices or Cataplasms)

"A plaster is a poultice allowed to dry to a shell, as opposed to being kept moist or replaced when dried out. The terms are sometimes used interchangeably… Although vile in many cases, and almost uniformly useless, they managed to stick around for quite a long time so may at least have provided what is now called a placebo effect"1. Plasters were an

Author and Teacher Pierre Dionis

important part of medicine at this time. Called by various names, including 'plaisters', 'emplaisters', cataplasms and poultices, they

consisted of herbs, brans, oatmeal and other plants that were boiled and cooled for application to wounds. French surgical teacher Pierre Dionis explains that plasters were "Compositions somewhat more solid than Unguents [salves] or Cerats [ceratum - ointments], and which are mollified [softened], in order to spread them on Linen or Leather; after which they are externally apply’d to all parts of the Body."2

Being a surgical teacher, Pierre Dionis had much to say about each of the four types of dressings we'll be discussing, so you can look forward to hearing a lot from him. His simple, often direct explanations were aimed at those who were just beginning in their trade as surgeons.

"The knowledge of Plaisters turns upon their Matter, Shape and Uses... For those applied to tender and sore Parts, as the Lips and Eyes, we make use of Taffata's and fine Linen. For the robust Parts, as the Arms or Legs, we use course Linen or Fustian, and sometimes Leather."3

1 "Plasters, Poultices and Paregoric: The Civil War Medicinal Cookbook", Civil War Interactive Website, gathered 9/9/2012; 2 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 25; 3 Ibid.

Plasters: Types of Plasters

Many different things went into plasters, depending on what the surgeon hoped to accomplish. Dionis explains that they are "compos'd of all things which we find on the Earth; Wax, Pitch, Oyls, and Greases, are the most common Materials; to them are added Litharge [lead], Ceruse [white lead pigment], Gumms, Liquors [liquid medicines, not necessarily alcoholic in nature], and an infinite variety of Powders, pursuant to the nature of the Plaister intended, and the Properties requisite".1

Nicholas Culpeper

Dionis explains that "Plaisters are necessary, in general, to retain the other Remedies, either in the Wound, or extended on its Surface; and in particular, to impress the Virtues of the Medicaments of which they are compos’d: With regard to this last Use, some dry and cicatrize a Wound as Diapalma; others concoct and digest the Pus or Matter, as Diachylon; others empty and cleanse, as the Mundicative; and others mollify and dissipate, as Diabotonum; and so of the rest."2 In support of this division of plaster types, herbalist Nicholas Culpeper also parses them into various categories, identifying some of the ingredients that he felt best represented their purpose.

Culpeper sorts plasters into three 'qualities', the first being, "Hot, as that for the stomach [and] Cold, as that of hemlock."3

The second qualities Culpeper identifies include:

Wood Betony

1. Mollifying [softening], as diachylon [a lead-based plaster], gratis dei, that of melilot [sweet-clover] and oxycroceum [a complex plaster containing saffron, pitch, yellow wax, turpentine, myrhh, frankincense and other components].

2. Binding, as of the crust of bread, and diaphenicon [possibly referring to fennel].

3. Drawing, as of betony [a grassland herb - Stachys], diachylon magnum [another complex plaster composed of litharge of gold, oils of iris, chamomile, turpentine, pine resin, yellow wax, and adhesives], with gums of melilot and oxycroceum.

4. Cleansing, as isis gal. de janua divinum.

5. Anodyne [pain-relieving], as of bayberries, melilot, oxycroceum.

6. Resolving [reducing - as in inflammation], as great diacliylon [lead-based plaster], with gums of cummin, bayberries, melilot, and oxycroceum.4

The third qualities of plasters sound obscure, but are actually terms that are used repeatedly in surgical manuals from this period. These include:

1. Suppurating [forming pus], as diachylon simple, the great with gums, and of mucilages.

2. Incarning [forming flesh in wounds], as of betony, diapalma, de janua, and nigrum [black pepper].

3. Glutinating [uniting the lips of wounds], as diapalma [a plaster of palm-oil, litharge, and sulphate of zinc] and nigrum.

4. Cicatrizing [healing by the creation of a scar], as diapalma.5

As far as the individual components that go into the various plasters, Dionis tells us that "some compose the Basis of the Plaister, and give it a Body; and others are added, in order to distribute and impart their Virtues to it, which pass from thence to the Part to which 'tis apply'd"6.

He also explains that once concocted, the plasters "may be long kept in Rolls without any diminution of its Virtue. This sort of Remedy, to which is allow'd a moderately hard Consistence, was contriv'd by the Ancients to foment, mollify or fortify the

Parts by Medicaments capable of staying on them several hours, nay, several Days without corrupting. When this Matter is to be us'd, 'tis held near the Fire, in order to spread and extend it on some soft Stuff."7

On the one hand, medicines that would last longer would be preferable to a surgeon on a ship where gathering fresh ingredients was impossible; everything the surgeon required had to be carried on the ship and parcelled out as carefully as possible. On the other hand, access to fire on a ship was limited. When the ship was traveling or in battle, fires would usually be doused for fear of catching the sailor's world of wood, rope and canvas on fire. This suggests that ship's surgeons would likely make smaller quantities of plasters and make them more often. Indeed, James Yonge referring to his time as a surgeon's assistant on a ship as 'slavery' explained that "spreading plaisters and fitting the dressings, was wholly on my hands"8.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 25; 2 Dionis,, p. 26; 3 Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper's English Physician and Compleat Herbal (1789 Edition), p. 47; 4 Culpeper, ibid; 5 Culpeper, ibid; 6 Dionis, p. 26; 7 Dionis, p. 26; 8 James Yonge, The Journal of James Yonge [1647-1721] Plymouth Surgeon, p. 41-2

Plasters: The Ship's Plaster Box

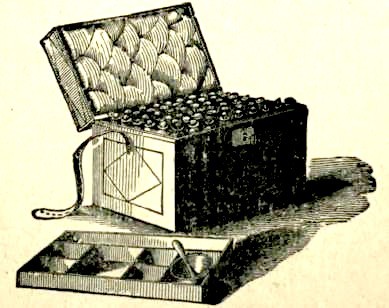

A Medicine Chest with a Plaster Box in the Foreground

Surgery is a practice that requires a lot of different instruments and a wide assortment of herbs and naturals required for creating medicines and wound dressings. A typical ship's surgeon brought a number of boxes to contain all of these things.

These boxes included a large medicine chest to hold his dry medical ingredients, a box (or a couple of them) which were custom designed for his delicate surgical instruments, a pocket kit of instruments that he always carried with him for emergencies and a plaster box designed to hold plasters, dressings and ointments.

Sea surgeon John Moyle gave us some detail of this plaster (or dressing box) as he explained how a surgeon should prepare himself and his gear for a sea voyage.

…you are to get [your chests], with your self and Crew, on Board; and see them placed in a dry Place, and as convenient to be come at as possible. And let your Surgery Chest be fast lashed that it may not over set in bad Weather by the rowling of the Ship.

And being on Board, see that your dressing box is furnished.

That is a box with 6 or 8 Partitions in it, and a Place for Plaisters ready spread. In the Partitions you put your Pots and Glasses of Balsams and Oyles for present use.1

Based on what James Yonge told us in the previous section, we know that the keeping and preparation of the plaster box was the duty of the surgeon's assistants on at least some ships. However, it may also have fallen to the surgeon, as was mentioned in some accounts. For example, upon returning to his ship after going ashore to obtain supplies for his medicine chest, surgeon Charles May was greeted by a surprise.

"He was immediately struck by the shambles of bales and chests on the deck and asked [first mate & recently turned mutineer John]

Photo: Marci Kroska

An example of a plaster box found at the Michigan Renaissance Festival

Madder, what have you got there, you are full of Business? His enquiry was met with a curse and a command to go mind his Plaister Box."2 So this could imply that the plaster box preparation was the surgeon's duty. It may also have been a curt dismissal from a man who had recently mutinied the crew, turned the ship pirate and didn't want to deal with a bunch of questions from a warrant officer they were probably going to need later.

The plaster box had to be kept well stocked and prepared because it saw daily use according to Moyle. He explains that "this Box as well as your pocket Instruments must be carried every Morning to the Mast between Decks, where our Mortar is usually rung, that such as have any Sore or Ailment may hear in any part of the Ship, and come thither to be drest. But such as by reason of illness cannot come thither you must go to them where Lye."3 So the plaster or dressing box had to be portable and allow for quick and ready use.

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 45-6; 2 Eric J.Graham, Seawolves: Pirates & the Scots, p. 172; 3 Moyle, p. 46

Plasters: Application and Removal

A plaster was specifically designed to fit the part that it was to lay upon. A piece of cloth or leather was cut to match the part and the mixture spread upon it and left to dry. Matthias Gottfried Purmann tells how it was applied to a patient in the case of a fracture. First you "apply your Plaister round the whole broken Part, not one side of the Plaister over the other, but let it want about and Inch and half of coming together. Over that apply a double Linen cloth larger than the Plaister, moistened in warm Wine Vinegar, and then wind it round with a Roller 3 Fingers broad, moisten'd also in Wine Vinegar, a hands breadth above and below the Fracture, moderate hard; but by no means exceed, lest you promote unhappy Accidents; for the Wet Cloths will shrink when they dry and make the Bandage fit closer."1 John Atkins advises that the "middle Part of the Plaster is to be applied on the Wound... (first cutting out so much as may leave room for Dressing)."2

Photo: Dolphin Danie

Surgeon Mission shaving a patient's head in preparation Of course, there are other factors that had to be considered. Charles Gabriel Le Clerc advised that when "you apply Dressings on a hairy Part, you must not forget to shave it, otherwise

the Emplaisters sticking to the Hair, would create a great deal of trouble in the taking them off; besides, these hinder the Remedies from taking effect, and the slovenliness of this would offend the Bystanders."3

Le Clerc also gives advice on the proper way to remove a plaster. To begin removal, the surgeon must "take hold of it by one Corner, and draw it off pretty quick. If you should draw it hastily it would create too much Pain, which is to be avoided as much as may be; and besides this, you might carry away with it some of the new-form'd Flesh: On the contrary, If you should do this slowly, you would keep the Patient too long on the Rack [in pain], and therefore you must observe a Middle between the two Extreams."4

He also warns that the surgeon "must never wipe an Emplaister and apply it a second time to the Wound, for besides that it is slovenly, it is impregnated with several Acids from the Wound, which will re-enter it, and increase the Malady."5 One would hope that Le Clerc was simply covering all the different possibilities rather than commenting on something that he had seen commonly done.

5 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiosa, p. 213; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 53; 3 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, A Description of Bandages and Dressings, p. 6-7; 4 Le Clerc, p. 8-9; 5 Le Clerc, p. 8