Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 9

Alcohol - Brandy

Photo: Jibi44 - 1804 Brandy Still, Arthez-d'Armagnac, France

The word brandy is derived from the Dutch word brandewijn - meaning 'burnt wine' - which refers to the fire used in the distilling process. As mentioned in the section on arrack, brandy refers to anything distilled from fermented fruit juice. However, non-wine brandies called by that name are typically prefixed with the type of fermented fruit from which the brandy was distilled - so if one wanted to call arrack a brandy, it would be referred to as palm brandy. For the purposes of this section, brandy will refer to liquids distilled from fermented grapes.1

Physician Peter Shaw explains, "Wine-Spirits and Brandies ...are the same thing; with this difference, that Wine-Spirit is the Spirit of a rich Wine, and Brandy the Spirit of a poor one"2. Although 'wine-spirit' is seldom used today, it does sometimes appear in period manuscripts.

Shaw goes on to further differentiate between types of brandies. He explains that just as each type of wine grape produces a different type of wine,

Artist: Jacob Gerritsz Cuyp - Wine Grape Grower (1628)

so does it also a Brandy of its own peculiar flavor: which is an observation that should be well attended to when any parcel of French Brandy is proposed to be imitated; for ‘tis ridiculous to expect Cognac Brandy should be perfectly resembled with a Quintessence made from Bourdeaux Grapes; though the Spirits, or subject matter of the operation were previously rendered ever so pure or tasteless.3

It should be noted that imitating alcoholic beverages was a common practice in England. Keep in mind that the politics of the time sometimes placed restrictions and extra taxes on French products, which is where most brandy came from. As Shaw himself explains, "The Brandies of France [are] in the highest repute... The French Brandies most generally esteemed are produced up the Loire, or near Cognac, Nants, and Rochelle. Next to these, are the Bourdeaux, or Entre deux Meres Brandies; those of Languedoc, and the Islands of St. Martin, Oleron, &c."4 French brandies were in great demand by the English upper classes, so they sold for a premium and thus were worth counterfeiting. However, this occurred on land when the brandy reached the wholesale or retail level, so would have been of little concern to the brandy consumed at sea.

The making of brandy likely goes back almost as far as the introduction of distilling.

Artist: Hector Hanoteau - Casked Product in France (1850)

"Commercial distillation of brandy from wine originated in the 16th century. According to one story, a Dutch shipmaster began the practice by concentrating wine for shipment, intending to add water upon reaching home port, but the concentrated beverage immediately found acceptance."5 Whether this bit of folklore is true or not, brandy was in wide use at sea and for trading in ports by the end of the 17th century.

Shaw explains that most of the French brandies come from grapes that are not fit for making wine. Such grapes "are usually first gathered, pressed, and their juice fermented, and directly distill’d. This rids their hands of their poor Wines at once; and leaves their Casks empty for the reception of better [wines]."6 He also notes that any French wines which are sour are "also condemn’d to the still."7 This makes some sense given that distilling removes much of the flavor of a fermented juice. "‘Tis a Rule with them to distil no Wines that will fetch any manner of price as Wines; for in this state the profits upon them is vastly greater than when reduced to Brandies."8

Ephraim Chambers gives a complete description of how brandy is made in his Cyclopaedia:

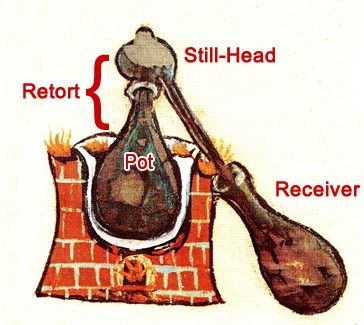

Simple Still on Medieval Manuscript

To distil Brandy, they fill the Curcubit [pot] half full of the Liquor from which it is to be drawn; and raise it, with a little Fire, until about one sixth part be distill’d; or till they perceive that what falls into the Receiver is not at all inflammable. This Liquor thus distill’d the first time, is called Spirit of Wine or Brandy; which Spirit, purify’d by another, or several more Distillations, is what we call Spirit of Wine rectify’d. The second Distillation is made in Balneo Mariae [bain-marie - a still with one container being suspended in another that contains boiling water] and in a glass Cucurbit, and the Liquor put therein, distill’d to about one half the Quantity: Which half is further rectify’d [corrected through further distillation in the bain-marie], as long as the Operator thinks fit.9

The politics between Britain and France and their effect upon the history of alcohol imports has already been discussed in the section on wine. However, there are still some interesting points concerning brandy in the political/societal arena that are worth mentioning. Distilling before the golden age of piracy was primarily the province of medicine, specifically the apothecaries who made medicines before the sixteenth century. Wine historian Tim Unwin points out that in France, "the production of brandy only emerged from the control of doctors and apothecaries when Louis XII granted the privilege of distilling it to the guild of vinegar makers in 1514. It was then further encouraged when Francis I also enabled the victuallers to distil it in 1537."10 Unwin notes that demand for brandy came from countries north of France because the wine often soured in long sea voyages where brandy did not.

The Dutch were particularly fond of brandy. They had been cultivating and even establishing small brandy distillation sites in Charente, France, taking what was an otherwise unexceptional, inexpensive wine and distilling it to create an industry which supplied Holland with brandy.

The

Cartographer: Nicolaus de Fer - Nantes and the Lower Loire River Area (1704)

Charente area is located about 120 miles southeast of Nantes. Historian Henriette De Bruyn Kops says, "The wines of the lower Loire area were deemed barely fit for human consumption but they made fine brandy. The Dutch introduced and commercialized the technology which distilled the Nantais wines into excellent brandy, a highly drinkable and thus marketable product."11

Unfortunately, with the start of the Franco-Dutch war in 1672, Holland banned French imports. This "was potentially disastrous for the young brandy industry… Fortunately for the producers in the Charente [and the lower Loire, north of it], a vigorous market in luxury beverages was emerging in the late seventeenth century in England."12 (England was on the side of the French in this conflict.) Brandy became even more popular through its exposure to soldiers and sailors, who "became accustomed to these new types of alcohol on campaign, or at sea, where brandy and other spirits survived better than wine"13. Naturally, when they returned home, many of them began asking for the beverage.

Brandy appears in thirty of the sailor's accounts under study, including four occurrences in navy sailor's accounts14, four occurances in navy officer accounts15, thirteen occurrences in merchant accounts16 and eleven occurrences in pirate accounts.17 These counts exclude references where punch or flip were being made using brandy

From John Cassel's Illustrated History of England (1865)

as they are counted in their own sections. Brandy also appears as plunder without specifically being mentioned as being drank in three pirate accounts.18 It is likely that the pirates drank at least some of this captured brandy, but since the citations do not explicitly state this, they are counted separately.

Perhaps the most interesting fact about English sailors and brandy comes in the victualling contract of 1677-8, which specified that "in lieu of a gallon of beer, a wine quart of beverage wine or half a wine pint of brandy, with which last all ships going to Guinea or the East or West Indies shall be supplied for half the proportion at least of the drink they shall be ordered to take in"19. This does not indicate whether the brandy was watered down like wine was in the Mediterranean, although since rum was served neat on at least some ships before Edward Vernon ordered it to be watered down in 1740, it is likely that some of the brandy was served the same way. Given its mention in the victualling contract, it is curious that more brandy citations do not appear in the naval literature under study.

While chief mate on the East Indiaman Fleet Frigate, Edward Barlow reported in 1702 that they

bought a little French brandy of some boats that came from Calais, it never having been ashore in any place in England, yet some ill willed people that knew of its coming on board made an information to the Custom House people at Deal, and they came aboard of us and seized it and carried it all away, about 85 gallons. So we lost it, and we fared the worse for it all the voyage, for the want of now and then a good dram.20

The men on the merchant ship Adventure were luckier than those on the Fleet Frigate. Surgeon Samuel Nixon reported the ships commander "so husbanded the Brandy allowed for them that they had Drams always when wet, and at the turning out of the Watches."21 This is seconded by Chief Mate Abraham Parrot, who said "that they had Drams [of brandy] Morning and Evening when fair, and as often as the Watches was chang'd when wet, never letting them go to their Hamocks wet without a Dram"22.

Many of the pirate citations only mention brandy in passing.

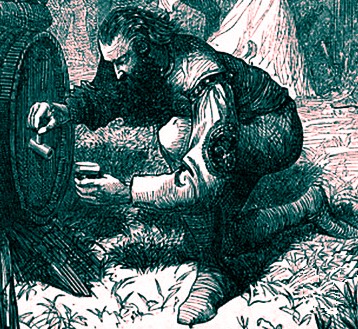

Artist: N.C. Wyeth

Preparing for Mutiny, From Treasure Island (1911)

For example, when John Halsey's crew were buying supplies from the Neptune (which had come to Madagascar to sell to the pirates), they provided "French brandy, Madiera wine, and English stout" to them23. A group of honest men who were engineering a mutiny against John Phillips' pirates after being forced aboard them provide a more interesting example of brandy use. The future mutineers were planning when carpenter Edward Cheeseman, "perceiving some Signs of Timidity in [Master Andrew] Harradine, he comes back, fetches his Brandy Bottle, and gives him and the rest a Dram, then drank to the Boatswain and Master [of the pirate ship], To their next merry Meeting, and up he puts the Bottle"24.

Brandy seems to have been a mainstay of some mutinies, providing the liquid courage needed to see the task through. When a group aboard the Abbington were planning to mutiny and turn pirate, Robert Sparkes and John Whitcombe promised a little incentive. "[I]n case the Captain did not serve the Ships Company with Brandy, he would give every one concern'd a small Case Bottle of Spirits, out of the Ships Cargo, to put in their Pockets"25.

1 “Brandy”, Britannica.com, gathered 10/30/17; 2 Peter Shaw, Three Essays in Artificial Philosophy, 1731, p. 128; 3 Shaw, p. 131; 4 Shaw, p. 130-1; 5 “Brandy”, gathered 10/30/17; 6 Shaw, p. 131-2; 7,8 Shaw, p. 132; 9 Ephraim Chambers, “Brandy”, Cyclopaedia, 1728, p. 124; 10 Tim Unwin, Wine and the Vine, 2005, p. 206; 11 Henriette De Bruyn Kops, A Spirited Exchange: The Wine and Brandy Trade Between France and the Dutch, 2007, p. 124; 12,13 Unwin, p. 208; 14 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 25, 29 & 235 & Samuel Pepys, Secretary to the Navy, 3 March 1688, Cited in Peter Macinnis, Bittersweet: The Story of Sugar, 2003, p. 97; 15 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 25, 154, 236,& 271; 16 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 531, Ed Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 251 & 254, Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 181 & 218, George Roberts, The four years voyages of Capt. George Roberts, 1726, p. 340-1, Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 16, 27, 171 & 177 & Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, 1734, p. 100, George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 6 & 26; 17 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 368, 469, 470 & 618, Fox, “7. James Kelly on two decades at sea. (London, 1700)”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 47, Fox, “47. John Fillmore’s narrative”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 233, Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618-1723), 1933, p. 33, William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1724, pp. 277, The Boston News-Letter, Monday August 15 to Monday August 22. 1720 & The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates, 1721, p. 41 & 42; 18 Fox, “3. John Sparks. The Examination of John Sparks, 10 September, 1696. HCA 1/53, f. 18”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 35, The Boston Gazette, 4/27-5/4/1724, “119. Trial of John Fillmore and Edward Cheesman. May 12, 1724”, Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period Illustrative Documents, John Franklin Jameson, 1923, p. 281; 19 J.R. Tanner, “Introduction”, Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library, Vol. 1, 1903, p. 167; 20 Barlow, p. 531; 21 Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 251; 22 Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 255; 23 Johnson, The History of the Pirates, p. 102; 24 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 348-9; 25 The Tryals of Captain John Rackam, and Other Pirates, 1721, p. 41

Alcohol - Brandy in Medicine

Brandy had a place in period medicine. Distilled wines are included in a large number of the recipes for medicines found in the sea surgeon's dispensatory including spirit of wine and rectified spirit of wine. Among the medicines found in the sea surgeon's dispensatory containing spirit of wine or brandy are Aqua Anisi, Aqua Celestis, Aqua Epidemica, Aqua Hungarica (Rosemary Water), Aqua Limoniorum (Lemon Cordial), Aqua Mirabilis, Aqua Peoniæ Comp, Aqua Viridas (Green Water), Elixir Vitæ (Elixir of Life), Elixir Vitrioli,

Photo: Robert A. Thom - An Apothecary Making Medicines

Extractum Catholicon, Fomentationibus, Fomentum Santivum (Healing Foment), Lixivium Fortis, Mel Vitriol, Resina Jallapæ, Spiritus Nitri Dulcis (Sweet Spirit of Nitre), Spiritus Salis Ammoniaci, Spiritus Salis Dulcis (Sweet Spirit of Salt), Tinctura Balsamica, Tinctura Castorei (Tincture of Castor), Tinctura Myrrhæ, Tinctura Piperis Stomachica and Unguentum Aragon, . It is also used to extract the medicinal virtues of various medicines including Pilulæ Rudii, Pulvis Ipecuanhæ, Pulvis Jalapii (Powdered Jalap) and Pulvis Resina Jalapii. Distilled wines were essential to medicines of the period.

In addition to the above medicines, surgeons sometimes recommended their own concoctions containing brandy when discussing particular health problems. Sea surgeon John Atkins notes that when making a plaster to apply to an external wound created by a foreign object, the surgeon could use oatmeal, which in the Navy "is boiled three Times a Week, (as good for use as any,) and may be made more serviceable by adding Wine or Brandy to your Water in boiling, and at the Conclusion throwing in a little U. Dialth [unguent of marsh mallow], or other Emollient [softening medicine]."1 Military surgeon James Cooke recommends an ointment made with spirit of wine as a topical medicine in venomous animal bites.2 Naval physician William Cockburn details a folk remedy consisting of "an Egg boiled in Vinegar, or Brandy, is a great Remedy for a Diarrhœa."3 Brandy is also recommended in drowning cases where it is given internally with treacle4 as well as being used to wet towels and rub the patient down5. For sprains, sea surgeon Moyle advised the surgeon to "Bathe and stuff the part well and hot (likewise) with spiritus vini communis [common spirit of wine], let this be done often".6

Atkins suggests applying "a warm Stupe wrung out of Sp. Vini [spirit of wine] when treating a Sarcocele or tumor of the testicle."7

Artist: David Ryckaert - The Surgeon (1638)

In fact, he relied on cloth wrung out of spirit of wine for a variety of purposes at sea. He advised his readers to have "Spt. Vini [brandy], some Pledgets ready spread with this"8 ready when preparing the ship's makeshift triage for battle.

Brandy was also used to force exposed bones in wounds to exfoliate or cast off their dead or damaged parts. When dealing with exposed bone in a wound, military surgeon Richard Wiseman recommends applying "Dossils [folded pieces of lint] dipt in spir. vini [spirit of wine] and Merc. præcipitat. [white mercury precipitate], with some little ol. terebinth. [oil of turpentine]"9. Wiseman also says that exfoliation of a bone exposed by a compound fracture can be speeded "by a little Ægyptiacum [a detergent ointment containing verdigris (copper acetates), honey and vinegar] and pulv. myrrhæ [powdered Myrrh] dissolved in spir. vini [spirit of wine], applied hot upon an armed Probe."10 Sea surgeon John Moyle suggests another, similar mixture containing brandy for the same purpose.11 French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis used "Pledgets dipt in Spirit of Wine to lay on the Bones which are cut" during amputation.12 He elsewhere orders that the surgeon use "only Pledgets moisten'd in Spirit of Wine, in expectation of their crumbling off, or Exfoliation [of the bone]."13

Brandy had an important place in surgery of the skull. Following trepanning (drilling a hole in the skill),

From Giovanni Andrea Della Croce, Chirugiae (1573)

the edges of the hole had to be filed to smooth them for healing. Moyle recommended that the rasped skull be washed with hot brandy followed by application of a plaster to facilitate healing.14 For a recently rasped skull, sea surgeon John Atkins advises a medicine containing spirit of wine, powdered bitterwort [gentian] root and honey of roses.15 He also employs it inside the trepanned hole in the skull by placing a piece of rolled, fine linen cloth dipped "in warm Spirit of Wine, and Mel Rosar. [Honey of Roses] mixed, [then] apply it smoothly to the bottom of your Perforation"16. Moyle recommended a concoction containing spirit of wine and syrup of roses to rinse the dura mater of the brain after trepanation.17 Richard Wiseman18 and Pierre Dionis19 both suggested a brandy-based concoction for cleansing head wounds. For wounds to the skull which did not require trepanning, sea surgeon John Woodall advised giving the patient a complex medicine the basis of which was spirit of wine.20 Although he uses brandy externally, Moyle warns that a patient recovering from head surgery should "not [be given] to drink Wine nor Brandy, nor any strong Liquor; but let only Barley water, or small [low alcohol content] Beer, be his constant drink, as other Wounded have."21

Brandy was often employed when sweating a patient as well.

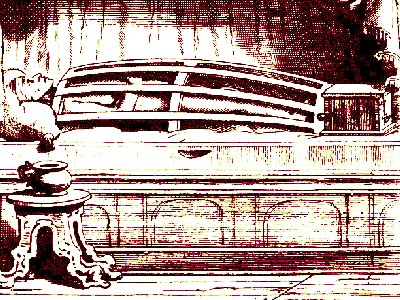

Sweating a Patient in a Frame, From Armamentarum Chirurgiae Appendix,

By Johannes Scultetus, p. 156 (1671)

Sweating was used to encouraged the body to eject unwanted humors from the body. Wiseman explains one procedure where the patient is put into a bed in a warm, sealed room and covered with a frame. "[T]hen a pan of well burnt Charcoal or Spirit of Wine must be put into the lower end of the Frame".22 In treating syphilis using this procedure, Johannes Sintalear explains that spirit of wine is best "because this Spirit by its oleagenous [oily] and most volatile Particles not only most powerfully penetrates thro’ the Pores, but also volatilizes [evaporates] the viscid slimy Part of the Venereal Poison, and expels it along with the Sweat out of the Body"23. To encourage sweating, sea surgeon Moyle gave an internal medicine containing theriac (or treacle) mixed with brandy.24

These are just some of the medical applications where brandy and spirit wine were used. To list them all would take a great deal more space. However, it should now be clear how much importance medical men ascribed to brandy during the golden age of piracy.

1 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 149-50; 2 James Cooke, Mellificium Chirurgiæ: Or, The Marrow of Chirurgery, 1693, p. 111; 3 William Cockburn, The Nature and Cure of Fluxes, 1724, p. 131; 4 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 99; 5 Thomas Cogan, Memoirs of the Society Instituted at Amsterdam in Favour of Drowned Persons for the Years 1767, 1768, 1770 and 1771, p. 3-4; 6 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 61; 7 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, 1742, p. 214; 8 Atkins, p. 149; 9 Richard Wiseman, Several Chirurgicall Treatises, 1686, p. 426; 10 Wiseman, p. 485; 11 John Moyle, Sea Chirurgeon, p. 8; 12 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 410; 13 Dionis, p. 414; 14 John Moyle, Memoirs: Of many Extraordinary Cures, 1708, p. 25; 15 Atkins, p. 88; 16 Moyle, Sea Chirurgeon, p. 111; 17 Moyle, Memoirs, p. 2-3; 18 Wiseman, p. 382; 19 Dionis, p. 287; 20 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 129; 21 Moyle, Memoirs, p. 115; 22 Wiseman, p. 497; 23 Joannes Sintelaer, The Scourge of Venus and Mercury, 2nd ed,, 1709, p. 234; 24 Moyle, Chirurgeon, p. 157-8