Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 15

Alcohol and Sailors: Alcohol Use By Sailor Type

Artist: Marcellus Laroon the Younger - Intereur mit Figuren (c. 1750)

Having looked in detail at the individual alcohols popular at sea among English sailors during this period and different ways and places in which it was consumed, it is worth reorganizing information to gain a better understanding of who drank what. It is usually true that most sailors would likely have drank whichever alcohol they could get, so some of this information is more dependent on ease of access than it is on personal preference. Naturally, when choices were available, people drank what they liked. When offered punch aboard one of pirate Edward Low's consort ships, George Roberts demurred and drank claret instead.1 William Snelgrave eschewed palm wine for various reasons and drank the 'European liquors' he had brought instead.2 One exception to the 'drinking what was available' rule was punch. Being a mixture of non-alcoholic ingredients including fruit juices, water, sugar and spices with whichever local alcohol can be procured, it was more readily available in any location, provided the sailors had access to the non-alcoholic ingredients. Of course, while punch was best made with all the ingredients, not all of them were needed or used as we have seen.

This article generally divides the types of sailors into three groups: naval, merchant and privateer and pirate. With these divisions in mind, the use of alcohols among each group will be discussed. This section will then conclude with a look at how the alcohols were used by all of the different types of sailors as a group.

1 See George Roberts, The Four Years Voyages of Capt. George Roberts, 1726, p. 41 & 47; 2 William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1724, introduction

Alcohol and Sailors: The Royal Navy

Artist: John Cleveley the Younger

HMS Resolution and Discovery in Port at Morea (c. 1780-90)

Of the three types of sailors the before-the-mast naval sailor's alcohol intake was the most regulated. While on a ship, the navy sailor was officially to be served a gallon of small beer a day1 until it ran out or went so bad that he wouldn't drink it. After that, the alcohol served him depended on where the ship was stationed. In the Mediterranean, he was to be served half a pint of brandy2 or a quart of 'beverage wine'. Beverage wine was to be three parts water and one part wine from "Naples, Provence, Turkey, Zante, or other places whose wine is of like goodness".3 In the West Indies, the navy sailors could be served a half-pint of rum, which may or may not have been watered down during the golden age of piracy, depending on the ship.4 Some ships in the East Indies also took arrack or palm wine on board which the men could drink, probably in the same measure as brandy - half a pint (although in one instance, they could only have it after they'd finished the beverage wine).5

While we know these regulations were in place, they do not seem to have been very well reflected in the actual period and near-period naval accounts. This is likely because the majority of the naval narratives used in this study come from the men serving in the Mediterranean: Chaplain Henry Teonge served aboard the Mediterranean-based ships Assistance (1675-6), Bristol (1678) & Royal Oak (1678-9). John Baltharpe was the Clerk on Mediterranean-based HMS St. David from 1669-71. Edward Barlow served

Image: The Jolly Sailor, Rich'd Kilby, Taylor & Salesman (1757)

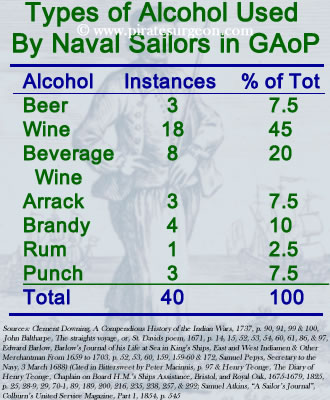

on several naval vessels, mostly in the Mediterranean and East Indies between 1661 and 1669. Since 31 of the 38 instances cited come from these three sources, the presence of wine among the alcohols in use by the common navy sailor is necessarily overstated. The chart seen at right clearly indicates this with 63% of the instances of alcohol being either wine or watered down beverage wine.

There are no detailed naval texts from the West Indies in this study, which is likely why the the use of the sanctioned rum is dramatically under-represented here. Punch gets a passing nod at 8%, mostly because it was given to the regular navy man during celebrations, which Teonge dutifully records. Beer also only provides 8% of the data, probably because once a navy vessel had gotten a couple months away from England it was either gone or gone bad and was replaced with local drinks such as arrack in the East Indies, rum in the West and wine in the Mediterranean. Most (if not all) of the beer served to navy sailors shipboard was small - or low-alcohol content - beer. All of the instances of arrack come from Clement Downing's account. Downing served in the navy in the East Indies beginning in 1715 until about 1722 or 23.

There are other factors limiting the accurate representation of alcohols used by the regular sailor in the navy. Historian J.D. Davies points out that "the gallon of beer to which they were officially entitled was insufficient for many seamen, who were eager to get hold of stronger fare. Some pursers and even some captains colluded in this by running illegal trades in liquor."6 However, the illicit use of alcohols is unlikely to be recorded in naval accounts printed during the period. It is also worth noting that most of the records of the alcohol drank at sea by the regular navy sailor refer to beverage wine, while, not surprisingly, regular wine was drank while in port. Sailors typically drank the local wine, probably because it was the least expensive.

The situation for the officers of a naval vessel was entirely different. So much so that it is not really fair to put both types of information into the same chart if an accurate understanding of reality is to be achieved. These men had access to a better quality of alcohol than the regular naval sailor as the

variety of liquors mentioned in Chaplain Henry Teonge's diary suggests. This is most readily apparent among the wine, which include wines from the Canary Islands, Florence, Syracuse, Germany, Alicante, Zante and Cyprus as well as sherries and clarets and other 'good' white and red wines.7 Wine was the drink of the upper class and, everything else being equal, would have been

Image Artist: Sir Godfrey Kneller

Image: Admiral John Jennings (c. 1708-9)

preferred by the officers, many of whom came from this strata of society. Teonge never mentions the officers drinking the watered down beverage wines.

Teonge also mentions drinking better beers including March beer8 - German Märzen beer, brewed in March and said to be "dark brown, full-bodied, and bitter"9 and Margate ale10 - also called Northdown and Mergate ale, which is believed to have been a relatively dark beer according to historian John Lewis.11 Margate ale was also mentioned as being dark by Sir Andrew Leake while he was being treated by naval physician William Oliver as mentioned in the section on beer.

Nearly all of the data found in this chart comes from Teonge's diary, which limits its effectiveness as a proxy for what naval officers drank during the period. Since Teonge served in the Mediterranean, arrack and rum are notably absent, although it is likely that given their apparent proclivity for drink, many naval officers would have enjoyed arrack and arrack punch in the East Indies and rum and rum punch in the West Indies.

Punch was ever-flowing among the officers on naval ships in Teonge's account; he specifically notes that it was 'as plentiful as ditchwater' on two of his ships12. He also explains that it was their 'woonted custum" to have two bowls of punch every evening while serving on the Assistance.13 The officers initially had access to cider, although he only notes that it was one of the 'suitable' alcohols the captain of the Assistance made available to the officers14, being brought aboard before they left England.

At 58% of the total, wines make up the majority of the alcohols consumed by the officers. In addition to the preference of men of higher standing for wine during this period, it also reflects the ship's Mediterranean location. It is actually somewhat surprising that brandy only comprises 5% of the alcohols, given that they were in wine country where brandy would also have been made. Of course, the punch (comprising 22% of the total) would most likely have had brandy as its alcohol base.

1 J.D. Davies, Pepys Navy, 2008, p. 152; 2 J.R. Tanner, “Introduction”, Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library, Vol. 1, 1903, p. 167; 3 Davies, p. 177; 4 See Samuel Pepys, Secretary to the Navy, 3 March 1688, Cited in Peter Macinnis, Bittersweet: The Story of Sugar, 2003, p. 97 and Ian Williams, Rum, 2006, p. 235; 5 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 91; 6 Davies, p. 156; 7 For examples, see Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 44, 51, 69, 72 & 81, among many others; 8 Teonge, p. 238; 9 Johann Georg Krünitz, Oekonomische Encyklopädie, 1773, Vol. 5, p. 156; 10 Teonge, p. 238; 11 Sally Jefferey, "The truth about Margate ale", thingsturnedup.wordpress.com, gathered 1/18/18; 12 Teonge, p 28 & 236; 13 Teonge, p 36; 14 Teonge, p 25 & 28

Alcohol and Sailors: Merchants and Privateers

Where the navy regulated the intake of alcohol of her regular sailors, merchants did not need to do so. However, men who were constantly drinking or drunk would have been poor stewards of the ship and a possible danger to themselves and others. Most merchants probably followed the example of the navy to some degree, serving lower-alcohol content beverages such as small beer and beverage wine during the day when work was being done. Keep in mind that most merchant sailors had served in (or were forcibly pressed into) the navy at some time, particularly early in their career. As a result, they would have been used to the routine of being served small beer and beverage wine.

By way of example, sailor

Artist: Abraham Storck

Southern Harbour Scene with Merchants (late 17th - early 18th c.)

Edward Barlow's first three posts were on navy ships, after which he got a few assignments to merchant vessels.1 Barlow preferred serving on merchant ships; when a navy press was implemented in 1664 during the first Dutch war, Barlow quickly signed on as a sailor on the merchant ship Mederosse to avoid the press. However, the ship only managed to sail as far as the Isle of Wight, where the Duke of York "ordered our voyage to be stopped and proceed no further, and caused all the men that were in the merchant ships to be put into men-of-war and frigates that wanted men, and the merchant ships which had goods in to be carried into Portsmouth Harbour."2

Based on the number of Barlow's complaints about the liquor on naval vessels3, his dislike of naval service was due in part to his dislike of beverages served to them. (He also complained about the food and treatment of the men by the officers, so alcohol was only one part of the problem in his mind.)

Many merchant sailors had it somewhat better than the navy when it came to choice of alcohols. In a letter to the owners of the merchant ship Adventure, Chief Mate Abraham Parrott wrote that commander Thomas Gullock provided "three Cans [mugs, not cans as we think of them] of [small] Beer a Mess every day till far beyond the Cape of good Hope, and after that two Cans of good Beer and Water"4. In addition to that, "they had Drams [of Brandy] Morning and Evening when fair, and as often as the Watches was chang'd when wet, never letting them go to their Hamocks wet without a Dram... Also that every Mess had on Sundays a Can of strong Beer; and when about the Cape [of Good Hope] in cold raw weather"5. This was verified in another letter to the owners written by the ship's surgeon, Samuel Nixon.6 This points out that merchant sailors were served small beer most of the time as mentioned previously. If this case is representative, although some of the alcohol found on a merchant ship was similar to that served in the navy, other alcohol seems to have been of a better quality.

Detail From British Sailor's Loyal Toast, From The British Tar

in Fact and Fiction, p. 136 (1738)

The number of merchant and privateer data sources is much broader than the number of naval sources, resulting in a little better distribution of the alcohol data and a more accurate representation of the alcohols merchants drank. These include Edward Barlow's various merchant voyages in the East & West Indies taken between 1662 and 1703, London merchant Francis Rogers' voyage in 1703 and 1704 in the same areas, captain George Roberts merchant journey in the West Indies and Atlantic during 1721-5, captain Thomas Phillips trading journey to the West Indies in 1693-4, William Snelgrave's pirate-interrupted trading voyage along the same route in 1719 and Woodes Rogers account of his privateering voyage of 1709 - 1712 to the West Indies, around South America and across to the East Indies, among others. An argument could be made that Rogers data - the only source for alcohols from a privateer ship that are included - would fit better with that of the pirates, but it was a legitimate voyage and it seems more appropriate not to dilute the pirate data with it.

The importance of a ship's location is obviously still important here; merchants in the West Indies could get cheaper and better rum, those in the East Indies had access to arrack and ships in the Mediterranean went in for wine and brandy. Unlike the navy, merchants and privateers were free to chose what they wanted buy for themselves and their sailors. While they could go cheap and procure inexpensive, lower quality beers and wines, their sailing recruits had a choice of ships (all other things being equal) and word would likely spread if an officer tended to serve low quality beverages, making it more difficult to man a ship. In fact, the watered down beverage wine is nowhere to be found in the merchant accounts. Instead, where the type of wine is mentioned, there is a scattering of what were considered better wines during the period including Madeira7, German Rhenish wine8, Canary9, Sherry10 and Shiras11. The same was likely true of beer. Francis Rogers mentions that while he was in Persia, they sometimes drank "English beer and French wine."12 Woodes Rogers also mentions South American wines from Chile and Peru13, but this was mostly because he was a privateer traveling in that area, which is in no way representative of the wine drank on most merchant vessels.

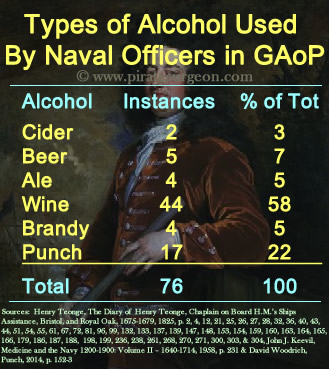

The distribution of alcohols found among the merchants and privateers is much more uniform than that of the

Image: Loading Tobacco (17th century)

navy. All of the primary alcohols under discussion in this article are well represented with the curious exception of rum, which holds only a measly 3% of the total alcohols. This is especially odd given how many of the voyages under study included the West Indies.

Wine is once again the most popular beverage at 26% of the total, followed closely by punch at 25%. While much of the instances of punch use are found in one source (Thomas Phillips), wine is fairly evenly distributed among all of the data sources. Beer holds a respectable 12% of the total beverages drank by the merchant and privateer sailors, again being fairly widely distributed among the various accounts, although the wine is used by them more than twice as often. Brandy and arrack each hold a respectable 17% of the total alcohols consumed by merchant and privateer sailors, something that can be chalked up to the locations where the ships sailed.

Several of the accounts mentioning arrack refer to fermented palm wine instead of the distilled product, probably because it was drank on land as a part of the ceremony of doing business with local denizens who had easy access to it. Merchant ship's captain Thomas Phillips came across it in Axim (in modern Ghana, Africa) and said it "was preferr’d by me before any other: it was extream pleasant, and in my thought drank like mead, or rather Verdy, or white Florence wine, as they call it at Livorno [Italy]."14 Captain William Snelgrave had the opposite impression of palm wine, noting "it did not agree with me."15 Since palm-wine turns sour in a day or two, it would not have usually been taken to sea. Only the distilled arrack would have survived there.

1 See Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 554-5; 2 Barlow, p. 93; 3 See Barlow's scathing comments on the beer on p. 127 and on beverage wine on pages 60 & 159; 4 Ed Fox, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 254; 5 Fox, p. 255; 6 Fox, p. 251;7 Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 186; 8 Phillips, p. 201; 9 Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 14 & George Roberts, The four years voyages of Capt. George Roberts, 1726, p. 11; 10 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 172; 11,12 Francis Rogers. from Bruce S. Ingram's book Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 182; 13 Woodes Rogers, p. 279 & 343; 14 Phillips, p. 201; 15 Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, 1734, p. 272

Alcohol and Sailors: Pirates

Captain Johnson referred many times to the pirates use of, even need for, liquor. In his account of the early life

Henry Every's Ship Fancy Attacking (18th century)

of pirate captain Nathaniel North, he noted that "all (who are acquainted with the Way of Life of a successful Jamaica Privateer) know is not an Example of the greatest Sobriety and Oeconomy."1 In his chapter on John Smith (alias Gow), Johnson says that after a voyage off the north-western coast of Africa where they failed to take any prize ships, the crew "resolv'd again for the Coast of Spain and Portugal, looking upon it as a great Hardship to be kept so long from good Liquor"2.

Perhaps most famously Johnson said that Blackbeard's Journal said: "Such a Day, Rum all out - Our Company somewhat sober – a damn'd Confusion amongst us! - Rogues a plotting. - great Talk of Separation. So I look'd sharp for a Prize, - such a Day took one with great deal of Liquor on Board, so kept the Company hot, damned hot, then all Things went well again."3 (As noted before, this is almost certainly apocryphal since no mention of a journal kept by Blackbeard is mentioned by anyone else, nor has one been found. Casting further doubt on the veracity of this claim, David Wondrich explains, "The interjections of "such a day" here are generally and wrongly interpreted as exclamations; they are, in fact, the editor's way of saying "day x" and "day y," rather than reproducing actual dates from the ship's log - if, indeed, he didn't make the whole thing up in the first place."4)

Several more practical examples of the pirates thirst for liquor exist. Clement Downing reported that they sold the pirates on Madagascar "several Hogsheads and Puncheons of Arrack [palm wine], and Hampers of Wine, for which they paid a very large Price, in Diamonds and

Artist: Howard Pyle

Pirate Counsel, From Jack Ballister's Fortunes (1894)

Gold Pieces of about 10 s. each."5 Captain Jacobs similarly reported high prices being paid by the Madagascar-based pirates for beer, wine and rum.6

Bartholomew Roberts, reported by Johnson to be less of a drinker than his men, established rules for drinking in the articles of his crew, apparently to prevent them from drinking so much. (At least that's how Johnson would have us believe it.) One ordered that after eight o'clock at night, "If any of the Crew, after that Hour, still remained enclined for Drinking, they were to do it on the open Deck; which Roberts believed would give a Check to their Debauches... but found at length, that all his Endeavours to put an End to this Debauch, proved ineffectual."7 Their first article read "Every Man has a Vote in Affairs of Moment; has equal Title to the fresh Provisions, or strong Liquors, at any Time seized, and may use them at Pleasure, unless a Scarcity (no uncommon Thing among them) make it necessary, for the Good of all, to vote a Retrenchment."8

While this sounds very egalitarian, it doesn't seem to have been practised very well. During the trial of Roberts' men, Johnson says that Harry Glasby testified "Most of the Ranger's Crew were fresh Men, Men who had been enter'd only since their being on the Coast of Guiney, and therefore had not so liberal a Share in fresh Provisions or Wine, as the Fortune's People... which had given Occasion indeed to some Grumbling's and Whispers"9. Alcohol was pervasive in the pirate world during this period, which is why it may not be surprising that there are more instances of pirates drinking alcohol in the period sea literature (116) than any other group under study (38 navy sailor instances, 76 navy officers instances and 65 merchant/privateer instances. Even if the navy men and officers were combined, there would still be 2 more pirate instances.)

The data for drink used by the pirates comes from a variety of sources. Some are secondhand accumulations of stories from

Artist: Joseph Nicholls

Blackbeard's Men Bringing a Barrel of Spirits to Be

Loaded on the

Queen Anne's Revenge (1736)

Newspapers, victim accounts and court trials such as Charles Gray's Pirates of the Eastern Seas, which focuses on the golden age up to 1723 and the two books of Captain Charles Johnson's General History of the Pirates (1724) and History of the Pirates (1728). (Note that the data used here comes from the Manuel Schonhorn edition of the book which gathers the two Johnson books together.) There are also a variety of first-hand pirate, victim and court trials used here, several of them being found in Ed Fox's Pirates in their Own Words and the accounts found in the books of pirate victims William Snelgrave (1719) and George Roberts (1721), among several other individual court documents and newspaper reports.

No less impressive is the number of individual pirate crews whose drinking habits comprise this data. These include the men serving with Thomas Anstis, Samuel Bellamy, Stede Bonnet, John Bowen, Joseph Bradish, Samuel Burgess, Dick Chivers, Thomas Cocklyn, Howell Davis, John Gilliam, Henry Every, William Fly, John Halsey, Thomas Howard, James Kelly, William Kidd, Olivier Levasseur, William Lewis, Edward Low, George Lowther, John Martel, Nathaniel North, John Phillips, John Plantain, Jack Rackham, Bartholomew Roberts, John Smith, Francis Spriggs, John (Richard) Taylor, Edward Teach and Palsgrave Williams, among others.

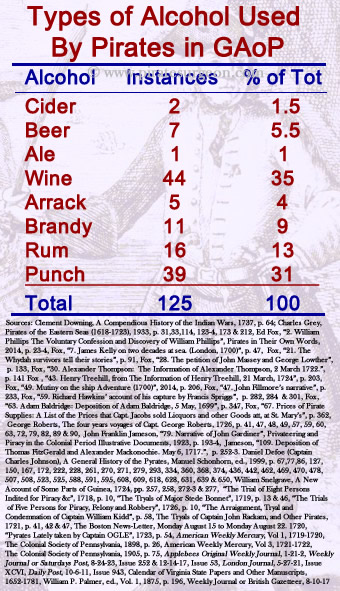

Looking at the data, it is notable how diverse the pirates' drinking habits were. This should not be surprising given the geographical range which many of them traveled over and the fact that their alcohol primarily

Henry Every's Ship Fancy Attacking (18th century)

depended on whatever they managed to capture from prey ships going to and from a variety of places. Still, all other things be equal, pirates seem to have preferred better alcohols. Lest we forget, at the mock trial held by Thomas Anstis' crew, they accused a man of 'worse Villainies' than piracy including being "guilty of drinking Small-Beer"10. When mutineer planners Phineas Bunce and Denis Macarty approached the supercargo of the Bachelor's Adventure, James Carr, they demanded "to be treated with a Bottle of Beer, for they knew Mr. Carr had some that was very good in his Care, which had been put on board, in order to make Presents of, and to treat Spanish Merchants with."11 When specific types of wine are mentioned, they include several of the better sort from the period, such as Claret12 and Madeira.13

Perhaps the most striking thing about the pirate alcohol use data is the dominance of two alcohols. Wines make up 35% of the total alcohols consumed and punch makes up 29%. Together, they comprise 64% of all the recorded alcohols drank by pirates during the golden age of piracy. Rum, the drink most often associated with pirates in popular culture, rates a very distant third in popularity at a paltry 14% of the total data. Brandy provides the only other double-digit percentage of pirate alcohols consumed at a just-above-the-cutoff 10%.

As noted several times previously, punch could contain any one (or occasionally two) of a variety of alcohols including rum, brandy, wine and arrack. If punch were excluded from this data and its component alcohol parts were listed with the other alcohols in this list, it is likely that those four alcohols would each receive a boost in its ratings. In fact, rum punch is either specifically mentioned or implied five times14, arrack punch twice15 and rum and brandy punch once.16 Still, it is curious that you rarely hear about wine or punch when people talk about golden age pirates when the data actually suggests these were their drinks of choice.

Rounding out the bottom 12% of the data are cider, beer, ale and arrack. The lackluster showings of these three alcohols are not particularly surprising. Given a choice, pirates would likely have favored more potent alcohols over beer and ale. It must also be remembered that beer and ale was rapidly consumed before it went bad at sea on naval and merchant ship. As a result, it would not be as readily available on prey ships in the Indies as other alcohols. Cider was generally difficult to come by and not favored for sea voyages, which probably explains its poor showing. It is actually surprising that there are even two examples of it on this list. The low number for arrack may reflect the fact that more Atlantic-based pirates are included in the data than East Indies-based pirates.

1 Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 512; 2 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 361; 3 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 86; 4 David Wondrich, Punch, 2010, p. 127; 5 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 64; 6 See Ed Fox, “67. Prices of Pirate Supplies: A List of the Prices that Capt. Jacobs sold Licquors and other Goods att, at St. Mary’s, 9 June, 1698…”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 362; 7,8 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 211; 9 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 271; 10 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 293; 11 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 628; 12 Fox, “21. The Whydah survivors tell their stories”, Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 91, Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618-1723), 1933, p. 33, George Roberts, The four years voyages of Capt. George Roberts, 1726, p. 47, 60 & 89 & Captain William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea and the Slave Trade, 1734, p. 257; 13 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 360, 442, 469 & 470 & Fox, “63. Adam Baldridge: Deposition of Adam Baldridge, 5 May, 1699…", Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 347; 14 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 222 & 588, Grey, p. 123-4, Fox, “67. Prices of Pirate Supplies: A List of the Prices that Capt. Jacobs sold Licquors and other Goods att, at St. Mary’s, 9 June, 1698…”, p. 362 & “The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet”, 1719, p. 13; 15 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 127 & 508; 16 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 436

Alcohol and Sailors: Conclusion

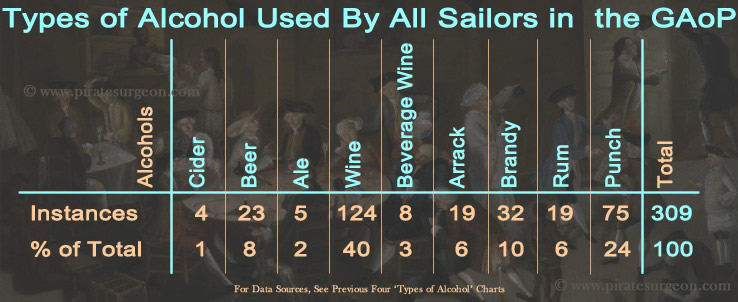

Although the data is much more meaningful being divided into the appropriate sailor subgroups, it is still interesting to look at it as a whole. Specific conclusions about its meaning as it impacts naval, merchant and pirate sailors are better gleaned from studying the sub-group data, but the overall data does support some trends seen in the subgroup data. First, the prevalence of wine becomes much more pronounced at 40% of the total alcohols used at sea. Only two other alcohols manage to achieve double-digit percentages in the grand scale: punch - at a still strong 24% and brandy at a much less impressive 10%. Taken together, these top three make up almost 3/4 of the total alcohols consumed by sailors on journeys. A second group of alcohols have fairly high single-digit percentages including beer, arrack and rum. This is probably because they each feature somewhat more strongly in some of the sailor sub-groups. The remaining three alcohols - cider, ale and beverage wine - even when added together make up a mere 6% of the total alcohols used at sea, probably for all the reasons already listed. In the end, wine was clearly king of the alcohols at sea, followed by punch based on this data.

Some Illustrations of Chafing Dishes Being Used to Heat Cautery Irons |