Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Alcohol Proofing

Before describing the types of alcohols found in the period sailor's accounts, it is worth discussing alcohol proof -

Distilling Spirit of Wine From

Hieronymus Brunschwig's

Liber de arte Distillandi (1512)

the percentage of alcohol found in a beverage - because of the modern interest in the subject and its popular association with the navy.

The medical profession had some interest in the proof of spirits, although they were not primarily concerned with the alcohol content (not that it could be accurately measured at this point anyhow), but in reference to how useful the liquor was to the medicines they were trying to create. Two alcohol building blocks specifically mentioned by several sea surgeons of the time were Spirit of Wine - a weaker proof liquid, being distilled once - and rectified spirit of wine - a stronger proof liquor, being typically distilled several times. Repeated distilling "corrected and cured [alcohols] of their natural, harsh, distasteful, unsavoury, or evil qualities, before they be compounded with ingredients, or extracted and drawn into rich or high Spirits, Strong-waters, or Aqua-vitæ; according to Art"1. Such pure spirits were consider useful by apothecaries in creating their 'strong waters'.

The apothecaries aside, alcohol proof was primarily of interest to distillers and the people who levied taxes against them called 'gagers' or gaugers. Chemistry historian William Jensen notes, "The proof system was originally established for purposes of taxing liquors according to their alcohol content and varies from country to country."2 It is from the history of acts to tax alcohol, the books of distillers and arguments between the two where we learn the most about how proof was determined and how it was used during this period.

In August of 1649, an act was writtien which mentioned using gagers to check the the distillers' supply of alcohol for the government. The Commissioners of Excise and their minions were given the power to engage "such and so many Gager or Gagers as they shall finde needful; which Gager or Gagers, and every of them, shall at all times be permitted to enter the Brew-house, and all other out-houses belonging to any Brewer, and to Gage all Coppers, Fats, and Vessels in the same"3. This act fails to spell out how the gagers might gauge the alcohol, although they seemed to be more interested in the amounts of alcoholic beverages distillers had and whether it matched what they were being taxed for than the alcohol content.

In 1688 an act was passed which placed duties on foreign alcohols which included "Single Brandy imported, [taxed at] 2s. the Gallon.; Double Brandy imported, 4s. a Gallon."4 This act again failed to spell out the method for gauging the alcohol, although it does mention "That true Notes in Writeing of the last Gauges made or taken by the said Gaugers shall be left by them with all Brewers Makers or Retailers of Beere Ale or other exciseable Liquors respectively ...at the times of their takeing their said Gauges

Artist: Martin Engelbrecht

Interior of a Distilling Laboratory,

From the Wellcome Collection (1720)

containing the quantity and quality of the Liquors soe gauged"5. There are a number of other acts governing taxation of alcohol during the golden age of piracy, many of which are based on the strength of liquor. Yet none mention the method for establishing that strength.

In discussing customs and taxation, historian William J. Ashworth explains that before an instrument was devised and accepted, there were three ways for establishing the strength of alcohol. The first used oil. "One of the oldest of these dated from the fifteenth century and worked by the addition of oil of a certain density to the liquor. The analysis was simple: if the spirit was strong, the oil sank; if it was weak, the oil floated."6 The second method was even easier to do, but harder to measure. "Perhaps the most popular and speediest technique was to shake the spirit in a glass vial and note the number of beads that formed at the edges of the surface, as well as the speed at which the beads formed and length of time they remained."7 Ashworth goes on to say this method was used throughout the eighteenth century. The third method, the one most talked about today in reference to sailors, was gunpowder proofing.

Gunpowder proofing is explained by distiller George Smith in 1725: "And for proof of your Spirit of Wine, put a little Gun-powder in a spoon, which fill up with Spirit of Wine, then set the Spirits on fire, and if they be perfectly deflegmated8 they will burn dry, and blow up the Gun powder."9 Note that Smith was not checking the proof of brandy, rum or any other popularly recognized alcoholic beverage, he was checking Spirit of Wine.

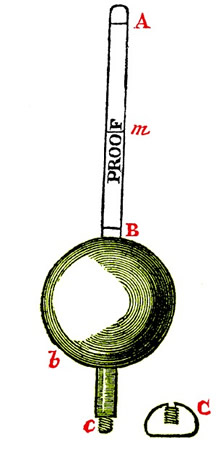

Clarke's Hydrometer, From "A New Kind of

Hydrometer" By J.T. Desaguiliers (1730)

John Clarke created a device that more scientifically measured the alcohol content of beverages in 1725, which was based on the existing glass hydrometers that were used by scientists of the time. He

was resolved to perfect the Hydrometer, for the Use of those that deal in Brandies and Spirits, that by the Use of the Instrument they may, by Inspection, and without Trouble, know whether a spiritous Liquor be Proof, above Proof, or under Proof, and exactly how much above or under; and this must be of great use to the Officers of the Customs who examine imported or exported Liquours10

A hydrometer is a floating device that measures the density of liquids by placing it into a liquid and noting either how much liquid it displaced or how much weight must be added to the hydrometer to make it displace the same amount of liquid as a known standard liquid (when measuring alcohol content, the standard liquid was proof liquor). One problem with hydrometers was that they behaved differently in the same liquids at different temperatures. Clarke was the first person to create a hydrometer that allowed the attachment of weights to the device which could be used to correct for this.

Clarke's hydrometer was made of copper with brass wire wound around it (b), a stem sticking out of the top indicated whether a liquid was proof (floating with the liquid level at m), under proof (floating with the liquid level between B and m) or overproof (floating with the liquid level between A and m). A variety of weights (one of which is shown at C) were included which could be screwed to the bottom of the hydrometer (c) to compensate for temperature variations at the distillery where measurement was taking place. (Presumably the weights would be tried in proof liquor until the one was found that made the hydrometer float so that it floated with the liquid level at m.)

Although it was technically around at the tail of the golden age of piracy,

Artist: Nicolas Bernard Lepicie

Excise Men Examining Goods in the Courtyard of the Customs House (1775)

Clarke's hydrometer wasn't in use until years later. It was sanctioned by the Royal Society in 1730 in their Philosophical Transactions publication. Once this was published Clarke's hydrometer "came into widespread use by the excisemen, and gradually by reluctant distillers and merchants"11. (The merchants and distillers preferred the methods they knew, most likely the bead test.) Even though it was in use by the gaugers, it wasn't mentioned in official documents until January of 1762. Even then, they stopped short of specifically naming the device: "Each gallon of brandy, or spirit of the strength of one to six under hydro meter proof. Shall be reckoned at 7 lb 13 oz. the gallon."12 Clarke wasn't specifically named in connection with his hydrometer in official documents until 1787.13

Clarke's hydrometer was officially replaced by Sike's Hydrometer in 1816, in part because Sike's device gave a specific measure of over and underproof. As historian William Ashworth explains, "overproof strength was expressed as, for example, one to ten, meaning that ten gallons of the spirits being tested might be reduced to proof by adding one gallon of water"14. Similarly, the amount of water which must be removed to bring underproof alcohol up to proof was indicated. Before this, the standard for proof had only been vaguely defined. "The standardised application of terms like PROOF and RECTIFIED only came slowly, and were certainly not universal by the end of the eighteenth century, so that spirit of wine was frequently used as a standard of strength"15. Sike's hydrometer was recognized as the official device of the British government for testing alcohols in 1818 at which time the primary standard for proof alcohol was defined as 12/13th the specific gravity of pure distilled water at the same temperature.

1 John French, The London Distiller, 1667, p. 2; 2 WB Jensen, "The Original of Alcohol 'Proof'," Journal of Chemical Education, 2004, p. 1258; 3 Her Majesty's Stationary Office, "August 1649: An Act for the speed, raising and levying of Moneys by way of New Impost or Excise", www.british-history.ac.uk, gathered 11/12/17; 4,5 "William and Mary, 1688: An Act for an Additionall Duty of [Excise] upon Beere Ale and other Liquors.", www.british-history.ac.uk, gathered 11/12/17; 6 William J. Ashworth, Customs and Excise: Trade, Production, and Consumption in England, 1640-1845, 2003, p. 264; 7 Ashworth, p. 264-5; 8 The phlegm - apparently referring here to impurities in the alcohol- will be removed by distillation. This process is described John Pechey in his Complete Herbal of 1694 beginning with brandy. Once the distilling equipment is set up, water is boiled under the brandy container and "the Spirit, which seperates from the Flegm... rises pure... until nothing more distils: Thus you have Deflegmated Spirit of Wine at the first Distillation." (p. 343); 9 George Smith, A Compleat Body of Distilling, 1725, p. 48; 10 J.T. Desaguliers, A Course of Experimental Philosophy, Vol II, 1744, p. 233; 11 Ashworth, p. 267; 12 The Scots Magazine, December 1761, Vol. 23, p. 620; 13 Ashworth, p. 268; 14 Ashworth, p. 276; 15 “Spirit of Wine”, Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities 1550-1820, British History Online, gathered 10/13/17

Alcohol Proofing: The British Navy?

You may be wondering what any of this has to do with the British Navy. Beginning around 2010, the number of books reporting a link between the Royal Navy and gunpowder testing of rum exploded (so to speak), resulting in this idea being repeated dozens of times in print. (It then ran rampant around the internet as well.) The template for such statements runs along these lines: "Proof developed in the eighteenth century when British sailors were paid partly in rum. To ensure that the rum had not been watered down, it was 'proved' to be undiluted by dousing gunpowder with the liquor and testing to see if the gunpowder would ignite. If it wouldn't, the alcohol content was considered too low, or underproof."1

Unless these sailors were testing their rum around or before the golden age of piracy, such statements make little sense.

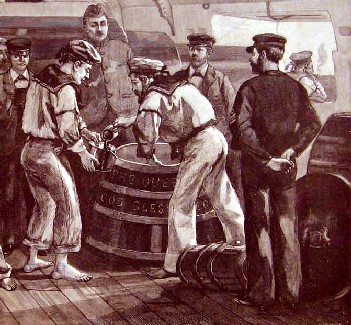

Mixing Water, Rum and Lime in The Scuttled Butt and Serving It As

Grog,

From Celebrating the Jubilee on Board a Man-of-War

(1887)

As briefly mentioned previously, Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon had ordered the practice of watering down the rum drank by Royal Navy sailors stationed in the West Indies in August of 1740.5

By the Seven Years War [1756-1763], the Admiralty had incorporated Vernon's instructions into naval regulations, and Vice Admiral Vernon's recipe won the navy enough of the ensuing battles to justify the suggestion of the sea god's favor. But instead of prescribing the amount of water to be added, the regulations referred to 'the usual proportion.' Evidence suggests that this was a three-to-one mix, but some captains made it four to one, and Admiral Lord Keith made it five to one - and certainly would have won no naval popularity contest as a result.6

Since watered down proof rum would be underproof and would consistently fail the gunpowder proof test, there would be no reason for a sailor to try applying the gunpowder test to his daily tot.

Some writers suggest the navy itself used the gunpowder proofing test to check the potency of their rum. This may have been possible before the introduction of Clarke's hydrometer as the standard, but being a government organization, they would more likely use the more popular bead method. One website states that when the Sike's hydrometer officially replaced Clarke's as the official proof checking instrument in 1818, the Royal Navy "collected 100 samples of rum diluted to 'proof' by the old gunpowder test, and then measured the proof of each sample using one of the new hydrometers."7

Sike's Hydrometer (mid-late 18th c.)

Alcohol strength was checked periodically to see if it conformed to naval regulations in the late 18th and early 19th century.8. However, the Navy used Clarke's hydrometer to test proof before 1818 just as the British government did. The Navy Board even sent Clarke's hydrometers "to the North American and West Indies Station to test all the rum"9 years previous to the adoption of Sike's hydrometer. So the story that gunpowder proofing was preferred over hydrometers by the Navy before 1818 is just a story.

The earliest reference to a navy-gunpowder proof connection is from a 1972 college textbook: “The term ‘proof’ originated with the British Navy, which tested the alcoholic concentration of its rum, by mixing it with gunpowder. If the mixture burned, that was 100 'Proof.'"2 The source for this statement is not cited, even though it is a textbook.

There are some books written before which mention both the idea that the navy required a certain proof rum and the idea that gunpowder was in use as an early proofing test. A 1945 article titled "The Royal Navy's Rum(pus)" explains, "The average strength of Navy rum on delivery must be 40% over proof, and the issuing strength 4.5% under proof, the proof spirit the proof spirit consisting of a mixture of 49.24 % alcohol and 50.76% water by weight." Later on the same page it says, "The old- fashioned method of determining whether rum was under proof was to mix it with gun-powder and then apply a flame. If the spirit was proof, or over, the powder would fire."3 Another article written eight years later provides the same percentage navy proof information followed by the statement: "The term ‘proof’ arose from the following test formerly employed by the Customs."4 However, neither of these citations directly link the Navy and gunpowder proof testing rum, the just mention them in the same discussion. So it may be that a beleaguered professor recalled reading something about the navy and gunpowder proofing rum and married the two ideas without checking them in an effort to get his book out on time in 1972.

1 Mark Bitterman, Bitterman's Field Guide to Bitters & Amari, 2015, p. 12 - I am not trying to pick on this particular author although there are two incorrect statements in that quote other than the notion that sailors gunpowder tested their rum. Sailors were not paid in rum, it was part of their daily fare. And proofing was likely developed in the sixteenth century by the alchemists and apothecaries, not the eighteenth.; 2 Justus Julius Schifferes & Louis J. Peterson, Essentials of healthier living: a college text in personal and environmental health, 1972, p. 77; 3 “The Royal Navy’s Rum(pus)”, Salt; Army Education Journal, Volume 11, 1945, p. 20; 4 Anne Sherman, “Quarterdeck: The Navy’s Rum”, Chamber’s Journal, November 1953, W&R Chambers, ed., p. 683; 5 Edward Vernon, Quoted by L.G. Carr Laughton, “Document: Grog”, The Marinier’s Mirror, Vol. V., No. 3, September 1919, p. 89-90; 6 Ian Williams, Rum, 2006, p. 235; 7 Simon Difford, "Navy Strength", diffordsguide.com, gathered 11/12/17; 8,9 Thomas Malcolmson, Order and Disorder in the British Navy, 1793-1815, 2016, p. 87

Alcohol Proofing: Golden Age Pirates??

Because golden age pirates were sailors, the gunpowder proofing idea occasionally gets attached to

Artist: Ivan Constantinovich Aivazovsky (1900)

them as well. The timing would be better since the hydrometer had not been invented and gunpowder, although not the most popular way to measure proof at this time, would have been the most convenient method for the pirates to test their alcohol's strength. However, given that pirates often stole a lot of their booze from other ships, they would have had no reason to bother checking the proof. (What would they do if it were underproof? Give it back?)

Proof or overproof spirits occasionally worked against the pirates as shown in the following account from William Snelgrave's captivity among the pirates Cocklyn, Davis and Levasseur.

About half an hour after eight a clock in the evening, a Negroe Man went into the Hold, to pump some Rum out of a Cask; and imprudently holding his Candle too near the Bung-hole, a Spark fell into the Hogshead, and set the Rum on fire. This immediately fired another Cask of the Same Liquor, whose Bung had been, through carelessness, left open: and both the Heads of the Hogsheads immediately flying out, with a report equal to that of a small Cannon, the fire run about the Hold.1

Perhaps they would have been better off with underproof liquors.

1 William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1724, pp. 272-3