Booze, Sailors & Health Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Next>>

Booze, Sailors, Pirates and Health In the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 8

Alcohol - Beverage Wine

Artist: Joseph Noel Syvestre (late 19th century)

Beverage wine is wine diluted with water which was served by the British Navy in lieu of small beer on ships serving in the Mediterranean. (John Kersey's dictionary tells us that beverage meant "a sort of mingled drink" in 17081.) It is not clear exactly when this practise began, although the specification for beverage wine appears in a victualling contract in December 1678:

instead of one gallon of beer, 'one quart of good, well-conditioned beverage wine of Naples, Provence, Turkey, Zante, or other places whose wine is of like goodness, without mixture, and of such strength as that it shall be able to preserve the water from stinking when three times the quantity of the wine shall be added to it in water, together with so much water as shall be commonly mixed with the said wine at the time when it is used by the seamen2

This ratio would have reduced the alcoholic content of the wine to about 1-3% by volume, making it comparable to small beer. Beverage wine was definitely in use before 1678, however. Naval clerk John Baltharpe mentions that his ship the St. David went out of their way to stop at Naples in October of 1670 specifically because they had "Bacon and Beveridge Wine to get, 'Cause at Legorn [Livorno, Spain]

Artist: Jacob Phillip Hackert - Port of Livorno, Spain (late 18th century)

we had not it."3

Three years before that, while serving aboard the 3rd rate naval ship Monck, Sailor Edward Barlow said "we took in ‘befriage’ wine from Alicante, but it proved worse news [referring to the political situation and how long the ship would be at sea], and so we took in ‘befraige’ wine here at Naples"4.

Working back through his journal to his second voyage on 5th rate Augustine and his first voyage to the Mediterranean in 1661, he said at Alicante "we took into our ship 100 butts or six pipes of ‘befraiage’ wine for the fleet, for our beer being almost done, we must now drink ‘befraiage’, which is a drink made of wine and water."5 He goes on to state that "His Majesty allows in his ships ‘befraiage’ wine, that one butt will but make four or five butts of water into ‘befraiage’; but our purser buys that which will make fourteen to one, having that a great deal cheaper"6. Ignoring the (probably exaggerated) ratio he claims the purser used, it is notable that Barlow suggests the mixture of water is four or five to one rather than three as stated by the victualling contract. This would further reduce the alcohol content, bringing it even closer to small beer. So beverage wine clearly pre-dates the victualling contract as the beverage given to before-mast men while sailing in the cradle of good wines, probably because it was cheaper and easier to get than beer there.

Artist: Hector Hanoteau (1850)

Unfortunately, beverage wine was considered anything but a good wine by those who had to drink it. Upon first encountering it, Barlow said the wine used "is as sour as any vinegar"7 and blames the purser for buying cheap wine. However, during his voyage on the 4th rate Yarmouth in 1668, Barlow again comments on the sourness of the beverage wine. So unless all the pursers were buying inferior wine, it is possible the watering down and the heat may have soured their wine, particularly if they had purchased the more fragile white wines that were popular in Alicante.

Barlow is not alone in this complaint; Baltharpe says,

Our Drink, it is but Vinigar and water,

Four-shilling beer in England's ten times better

So that when Saylors gets good Wine,

They think themselves in Heaven for th' time8

Writing in 1681, Sir Robert Robertson aboard the naval vessel Assistance noted that, "The beverage wine so bad that men choose rather to drink water."9 Note that he didn't drink it; the officers had regular wine available to them.

Beverage wine is mentioned eight times10, only in English Navy accounts. The pirates, who turned their noses up at small beer as explained previously, would probably have thrown it overboard if they came across it. Skin-flint merchant ship owners might have used it, although if this were known, it would have made it much more difficult for them to recruit crew.

From a health perspective, beverage wine was theoretically better than regular wine. Physician Tobias Venner advised "that wine much allayed with water, doth better quench thirst than water alone."11 He explained that "wine diluted is good for young men...

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger

Drinking Man, From Ship With Revelling Sailors (1532-3)

for [people in] hot Countries, and the hot seasons of the yeere, especially in the Summer; for then by reason of the parching heat, wine allayed, that is to say, thin, small, waterish, and in no wise strong, is to be drunken."12 Venner's recommended combination of wine and water sounds quite familiar: "let three parts of water be mingled with one of wine; or if the time be very hot, and the thirst molestious, and the body also youthfull, and strong, foure parts of water may be mingled with one of wine."13 One wonders if the navy had a copy of his book when they started this tradition. Fellow physician George Cheyne wrote in 1725 that "rich, strong, and heavy Wines ought never to be tasted without a sufficient Dilution of Water"14.

Not everyone was quite so enthusiastic about the medical benefits of beverage wine. Barlow complained that "the sour ‘befraiage’ ...many times in hot weather bringeth a man to the ‘flukes’ (flux - diarrhea), and many die of that disease in hot countries"15. While Barlow had a tendency to whine about such things, he had strong backing on this point. Surgeon John Moyle noted that "Eager [sour] Beverage Wines that we usually drink in the Streights [probably the Straights of Gibraltar] hath caused Fluxes [diarrheas]"16. In another volume, he explained, "Fluxes are very frequent at Sea, especially when the victuals grow bad; or when we come in Countries where we get abundance of bad Wine and beverage"17. Note that Moyle here refers again to 'sour' wines. It is worth recalling that the English had a particular taste for sweet, alcoholic wines, rather than the dry, white wines which may have been found in parts of Spain.

1 John Kersey, "Beverage", Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, 1708, not paginated; 2 J.R. Tanner, “Introduction”, Naval Manuscripts in the Pepysian Library, Vol. 1, 1903, p. 177; 3 John Baltharpe, The straights voyage, or, St. Davids poem, 1671, p. 60; 4 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 159; 5,6 Barlow, p. 53; 7 Barlow, p. 54; 8 Baltharpe, p. 54; 9 J.D. Davies, Pepys’s Navy, 2008, p. 202; 10 Baltharpe, p. 54 & 60, Barlow, p. 54 & 159, Davies, p. 202, Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 71, 89 & 200; 11,12 Tobias Venner, Via Recta ad Vitam Longam, 1638, p. 39; 13 Venner, p. 40; 14 George Cheyne, An essay of health and long life, 1725, p. 50; 15 Barlow, p. 54; 16 John Moyle, Chirugius Marinus: Or, The Sea Chirurgeon, 1693, p. 181; 17 John Moyle, Abstractum Chirurgæ Marinæ, 1686, p. 100

Alcohol - Arrack

Although rum may have been the alcoholic beverage of choice in the West Indies during

Photo: Midori - Palm Sap from Toddy Palm

the golden age of piracy, arrack was the king of liquors in the East Indies. The word arrack come from the Arabic word for ‘sweat’ or ‘juice’.1 Physician Peter Shaw noted in 1731 that 'arrack' "is a general and familiar name in the East for all kinds of Brandies; as the word Spirit is with us."2 The mention of brandy here may sound odd, but Shaw elsewhere explains, "In the general sense, they [brandies] include all kinds of spirits considered in a State of Proof; or as consisting of an equal weight of Water and Alcohol."3

Two types of arrack are found in the sailors accounts from around the period. The first was obtained from the sap of palm trees and was also referred to as rack4, toddy or nero5 and malaso6 in the accounts. It often called palm wine today. The second was made from sugarcane. William Dampier noted that the natives he encountered called this type of arrack 'bashee'.7 However, being a generic term, arrack can also refer to alcohol made from rice, dates, raisins and similar locally available foods. Despite this plethora of spirits, Shaw explained "beyond dispute, the finer Arracs are made of the Juice of the Cocoa-Tree, or the Palm-Tree: tho’ other trees also may afford Juices fit for the same purpose"8. This section focuses on arrack derived from palm trees.

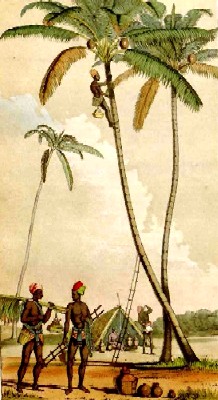

Photo: Biswarup Ganguly - Palm Sap Collection in West Bengal

Palm-based arrack was distilled from palm wine. The making of palm wine seems to have fascinated the period sailors; five different sea authors describe it in some detail including Charles Johnson, the author of the General History of the Pyrates.9 However, it is physician Shaw who gives the most colorful description of gathering the palm sap:

It seems the Operator, being provided of a sufficient stock of small Earthen Pots, with Bellies, and Necks, like our ordinary Bird Bottles [referring here to calabashes]; he fastens a parcel of them to his Girdle, or otherwise commodiously about him; and thus equipp’d, swarms directly up the tall trunk of the Cocoa-Tree: when coming at the Boughs, he with a knife cuts off certain little Buds, or Buttons, and immediately applies a Bottle to the wound. And having thus applied, and dexterously supported his whole number of Bottles, as so many Receivers, for the Liquor to distil into, he descends. This is usually done in the Evening; the Tree bleeding more freely in the night. Next Morning the Operator takes off his Receivers, and empties them into a proper Receptacle; where, of itself, the Liquor spontaneously ferments.10

Dutch East India Company factor William Bosman recorded some other interesting details on the making of palm wine

Photo: Balaji Jagadesh - Gathering Palm Sap with a Reed Pipe in India

which add to Shaw's description, although they also differ in some respects. Bosman says that when a tree is prepared to give sap, "they are bereft of all their Branches, and rendered intirely bare; in which condition having remained a few Days, a little Hole is bored in the thickest part of the Trunk; into which is inserted a small Reeden Pipe; and that thro' the Palm-Wine drops into a Pot set under to receive it"11.

He also explains that once a palm tree is tapped, "it yields Wine for twenty, thirty, or sometimes more Days; and when it hath almost run its last, they kindle a Fire at bottom, in order to draw more Wine with the greater force."12 Once the supply of sap is exhausted, Bosman says the tree "is fit for nothing but firing"13. Agriculturist John Worlidge reports that "two Gallons of this Liquor may be drawn in a day, without any damage to the Tree"14. However, he also mentions that if too much of the sap is extracted or it is done too late in the season, it may inhibit the tree from growing coconuts.

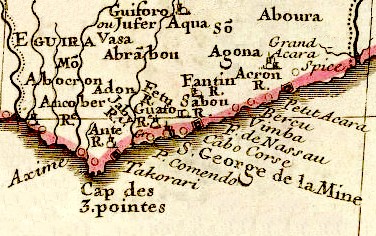

Cartographer: Guillaume de L'Isle - Map Of Area Discussed (1707)

Bosman discussed four kinds of palm wine which were made in various small villages in Africa located around modern Cape Coast, Ghana. (See the map at right. Cape Coast is 'Cap des 3. pointes' on that map.) The first type of palm wine was that he described in the previous paragraph. The second, called Quaker, he said had a more pleasant flavor, was twice as strong as the first type, being made at 'Fantyn' (Fantin). He noted that it came from trees that "are not above half as big as the right Palm-Trees ('right' palm trees may refer to toddy palms, although this can't be verified from this comment)."15 The third type of palm wine, referred to as 'Pardon', was as 'pleasant' as Quaker but less potent, being made at 'Ancober', 'Abokron' [Abocron], 'Axin' [Axim] and 'Ante' [near Dixcove?]. He explained that Pardon was drawn the way suri [sura] was in India. The fourth type of palm wine, which he called Crissa, came from Ante, Jabi [Jaby] and Adom [Adon] being "utterly void of all manner of strength; but when drank fresh tastes like Milk"16.

Modern mixologist David Wondrich explains that the fermented palm wine is what was referred to as toddy. He explains that arrack is actually produced through distillation, the result being divided into "three grades, depending on strength. ‘Feni’ or ‘fenny’ was the strongest, plain old arrack the intermediate and ‘sura’ the weakest"17.

Photo: Wiki User SilentBobxy2 - Modern Distilled Palm Arrack

Writing in 1731, Shaw describes the process of distilling arrack from the fermented palm sap.

When the fermentation is over, the weak Wash [the palm wine], now grown a little tart or acid, is put into the Still, and drawn down to a Low-Wine: which is so very dilute and poor a Liquor, as soon to corrupt and spoil by keeping. For which reason, to make it stronger, they rectify it in another Still, to that very weak kind of Proof-Spirit we commonly find it18

Double distilled liquor was generally around proof strength (50% alcohol by volume), which is why it was called 'Proof-Spirit.' Only one of the five sea authors hints at the distillation of palm wine to produce arrack, which is curious given that Shaw suggests double-distilled fermented palm sap was the arrack that the English purchased and drank. It is none other than pirate's Boswell, Charles Johnson, who mentions that "It is from these Wines [the palm wines drawn from the trees on Principe Island] they draw their Arrack in India."19 (As mentioned, he only hints at distillation of the palm wine.)

Like the naming of the alcohol, there is some confusion about the taste, mostly because most of the period sailors failed to differentiate between the fermented palm wine (toddy) and the distilled arrack. Of palm wine, Merchant sailor Nathaniel Uring said, "I have tasted it, but found it disagreeable; but when it is first taken from the Tree it has a very pleasant Taste, and I have drank great Quantities of it without perceiving it had any other Effect than quenching my Thirst, though some Travellers affirm that it will make People drunk."20

William Bosman says, "This Wine being drank fresh or under the Trees, as our Phrase runs here, is very delicious and agreeable; but withal so strong, that it unexpectedly steals to the Head, and very speedily intoxicates"21.

Photo: Wiki User Dhruvarahjs

Palm Wine in Bottles and Glass

Bosman's research into the different types of palm wine and their different strengths might explain the differences in strength he and Uring encountered. Although he also notes that "that which the Peasants bring daily to the Shore [probably to sell to sailors] is not worth much, because it is impoverished and adulterated; and I believe it is ...very much vitiated by a pretty large mixture of Water."22

Pirate historian Charles Johnson notes that palm wine "is of a wheyish Colour, intoxicating and sours in 24 Hours, but when new drawn, is pleasantest to Thirst and Hunger both"23. Sailor Francis Rogers agreed, noting that palm wine "won’t keep well a whole day, the hot weather turning it sour."24 Edward Barlow adds that it is a "very good for drink whilst it is new, but soureth presently, and then it serveth for vinegar."25

Interestingly, the change to vinegar may not necessarily have been a bad thing (provided your goal was something other than intoxication), for John Worlidge notes that palm wine "turns into very good Vinegar."26 Uring explains that the men of Angola intentionally leave the palm sap out for two days "in which time it ferments and grows sower, and has some Spirit in it, which exhilarates them and makes them merry; they’ll set at these drinking Bouts twelve Hours together till they get drunk."27

None of the period authors really go into detail about the flavor of the distilled arrack, possibly because it would have been distilled to proof, removing much of the original flavor.

Photo: David Stanley - Arrack Still in Southern Ethiopia

Modern author David Wondrich suggests that it has a "sourish, lightly funky" flavor.28 He also suggests that "was probably better than any other available spirit save the most carefully sourced French cognac, [although] it was nonetheless a taste that needed acquiring"29. (Your author finds the term 'sourish, lightly funky' to be a pretty good description from his tasting. If you chase it with really good rum, a light coconut flavor appears for some reason.)

Whatever their opinions, many English sailors seem to have enjoyed arrack. Navyman Clement Downing noted that when the Indian pirate Angria's men "take any Ships belonging to the Portuguese or English, they reserve a quantity of the Arrack on board to gratify any Europeans that shall enter into their Service."30

Palm arrack appears as a standalone beverage in nineteen of the sailor's accounts under study, including three naval instances31, eleven merchant and privateering instances32 and five pirate instances.33

While sailing on the Septer, an East India ship, in 1697, Edward Barlow explained that they stopped at Goa, India "to buy our sea store of rack. Arriving there the 16th at night, the 17th we bought [ar]rack, paying eleven ‘perdos’ the keg for small, which is sterling sixteen shillings and sixpence and their cask returned again, and their treble stilled rack 22 ‘perdos’ the keg, which is 33 shillings."34 Being casked, this was almost certainly the distilled arrack.

Photo: Louis Van Houtte

Collecting and Distilling Arrack (1850-1)

Clement Downing says that the East India Company fleet picked up arrack at Goa in 1723 or 1724.35 He also reported that around 1721-2, some of the arrack on board the Salisbury was sent to the Fort at St. Philip's Bay36 and some of what remained was sold to the settled pirates on Madagascar.37 However, the crew also drank it... when they were allowed. Downing reported that after some sour Madras India wine had been brought on board the vessels Salisbury, Exeter and Shoreham, "the Ships Crews [were] compelled to drink the same, before any Arrack was allowed us."38

Perhaps the most famous example of pirates procuring and drinking arrack comes from the account of John (Richard) Taylor's crew. When Taylor's ship arrived at Cochin (modern Kochi, India) they saluted the fort there by firing their guns eleven times. This appears to have been a signal to the Dutch traders, who appeared in the figure of John Trumpett that evening "bringing a large boatload of arrack which they received with abundance of joy, demanding more."39 Trumpet explained that he had brought all that Cochin could supply them, about 180 gallons in leaguers (small 20 gallon casks) along with 60 bundles of sugar cane. (Clearly they were going to use the arrack to make punch. More on that shortly.) Before they left, Trumpett managed to procure more arrack for them; perhaps with such good and moneyed customers in the offing, the locals had been working overtime tapping the palm trees and working the stills.

Not a lot is said about the health problems or benefits of either palm wine or arrack. While on a plantation in Jamaica, physician William Hughes mentioned drinking his "mornings draught of this pleasant Wine."40 He warns that it should be drunk in moderation, no more than a glass in the morning. He explains that "it is of a penetrating quality; and therefore and excellent Diuretick: it is also the most effectual for preventing and curing the [kidney] Stone, Collick and Strangury [frequent, painful urination], being applied with judgment, or else it may offend the head; and doubtless it may have many other vertues which I am unacquainted with."41

From The General History, Dutch ed. (1725)

Surgeon Lionel Wafer also discusses a health problem he associated with palm wine in his usual amusing manner, although his charges didn't seem to understand how palm wine was properly made. Let's finish with this marginally medically relevant (but somewhat entertaining) account of what happened to some of the privateers who went ashore at lush Cocos Island off Costa Rica during one of the privateering voyages:

[O]ne Day among the rest [of the privateers], being minded to make themselves very merry [remember: codeword for drunk], they went ashore and cut down a great many Coco-trees; from which they gather’d the Fruit, and drew about 20 Gallons of the Milk [apparently thinking this would make palm wine]. Then they all sat down and drank Healths to the King, Queen &c. They drank an excessive quantity; yet it did not end in Drunkenness. But however, that sort of Liquor had to be chilled and benumb’d their Nerves, that they could neither go nor stand: Nor could they return on board the Ship, without the Help of those who had not been Partakers in the Frolick: Nor did they recover it under 4 or 5 days time.42

Who know coconut milk could be so caustic?

1 David Wondrich, Punch, 2010, p. 26; 2 Peter Shaw, Three Essays in Artificial Philosophy, 1731, p. 142; 3 Shaw, p. 130; 4 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 493; 5 Francis Rogers. from Bruce S. Ingram's book Three Sea Journals of Stuart Times, 1936, p. 183; 6 Nathaniel Uring, A history of the voyages and travels of Capt. Nathaniel Uring, 1928, p. 42; 7 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, 1968, p. 291; 8 Shaw, p. 142; 9 Barlow, p. 212, William Bosman, A New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, 1705, p. 285-6, Daniel Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 187, Francis Rogers, p. 182-3, Uring, p. 42; 10 Shaw, p. 142-3; 11 Bosman, p. 285; 12,13 Bosman, p. 286; 14 John Worlidge, Vinetum Britannicum, 1678. p. 3; 15 Bosman, p. 286; 16 Bosman, p. 287; 17 David Wondrich, Punch, 2010, p. 71; 18 Shaw, p. 143; 18 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 187; 20 Uring, p. 42; 21,22 Bosman, p. 286; 23 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 187; 24 Francis Rogers. p. 183; 25 Barlow, p. 212; 26 John Worlidge, Vinetum Britannicum, 1678. p. 3; 27 Uring, p. 42; 28 Wondrich, p. 71; 29 Wondrich, p. 206; 30 Clement Downing, A Compendious History of the Indian Wars, 1737, p. 151; 31 Downing, p. 90, 91 & 100; 32 Barlow, p. 212, 493 & 540; Bosman, p. 286, Thomas Phillips, 'A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal', A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VI, Awnsham Churchill. ed., p. 233, Francis Rogers. p. 201, Woodes Rogers, A Cruising Voyage Round the World, 1712, p. 385, 392 & 398, William Snelgrave, A New Account of Some Parts of Guinea, 1724, introduction & p, 50; 33 Defoe (Captain Charles Johnson), p. 523, Downing, p. 64, Ed Fox, “49. Mutiny on the ship Adventure (1700)”, Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 206, Fox, “56. Richard Lazenby, a prisoner of John Taylor, from The Narrative of Richard Lazenby", Pirates in Their Own Words, p. 284, Charles Grey, Pirates of the Eastern Seas (1618-1723), 1933, p. 114; 34 Barlow, p. 493; 35 Downing, p. 100; 36 Downing, p. 91; 37 Downing, p. 64; 38 Downing, p. 91; 39 Ed Fox, “56. Richard Lazenby, a prisoner of John Taylor, from The Narrative of Richard Lazenby", Pirates in Their Own Words, 2014, p. 282; 40 William Hughes, The American Physitian, 1672, p. 58; 41 Hughes, p. 59; 42 Lionel Wafer, A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America, 1903, p. 176

Sugarcane Arrack

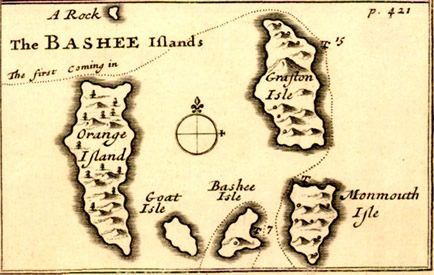

The Bashee Islands, From A Voyage Round the World, By William Dampier (1699)

Buccaneer and adventurer William Dampier discusses another drink that is called also called arrack which is made from sugarcane. He explains that the natives of an island in the modern Batanes, north of the Philippines "make a sort of Drink with the Juice of the Sugar-cane, which they boil, and put some small black sort of Berries among it. When it is well boiled, they put it into great Jars, and let it stand three of four Days and work. Then it settles, and becomes clear, and is presently fit to drink."1 Based on this, Dampier decided to name the island where he witnessed this 'Bashee', and referred to the five islands he saw around it as the Bashee Islands.

This was not the introduction of sugarcane arrack to the English, however. Writing twenty years before Dampier, David Worlidge said, "In the East-Indies, they extract an excellent Liquor which they call Arak, out of Rice, Sugar, and Dates"2. Worlidge goes on to refer to it as "a kind of Aqua Vitae, much stronger and more pleasant than any we have in Europe."3 This means that the arrack he was talking about was a distilled beverage.

It is possible that Dampier's reference to the liquid being 'well boiled' refers to a type of still used in the

Artist: Thomas Murray - William Dampier (1697-8)

orient which is different than that to with which the English were familiar. David Wondrich describes it as "a woklike cover full of cold water to induce condensation, with a cup underneath it, inside the still, to collect what drips off the bottom of the wok. It is then drawn out by a pipe through the side of the pot."4

Dampier said that this arrack was "an excellent Liquor, and very much like English Beer, both in Colour and Taste. It is very strong"5. Writing in 1842, Royal Navy Assistant-Surgeon Arthur Adams gave a very different description of sugarcane wine, stating that it "is a thick yellow fluid, of a subacid taste, between that of cyder and toddy, and is not very potent in its effects."6 Modern author Dr. Priscilla Chinte-Sanchez says "Traditional basi is a sweet-sour, effervescent, turbid, alcoholic beverage... The color varies from a dark cloudy to a sparkling golden brown hue."7

Dampier also offers an opinion on the medicinal properties of this alcohol. "I do believe very wholesome: For our Men, who drank briskly of it all day for several Weeks, were frequently drunk with it, and never sick after it."8 Even though he doesn't really provide as much of a medical perspective as he promised, at least his readers know that it won't give them a hangover.

1 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World -1697-, 1968, p. 291; 2 John Worlidge, Vinetum Britannicum, 1678. p. 10; 3 Worlidge, p. 11; 4 David Wondrich, Punch, 2010, p. 27; 5 Dampier, p. 291; 6 Sir Edward Belcher, Arthur Adams, Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S Samarang, Vol. 1, 1848, p. 71; 7 Priscilla Chinte-Sanchez, Phillipine Fermented Foods, 2008, p. 124; 8 Dampier, p. 291