The Politics of Sea Surgery During the GAoP Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

The Politics of Sea Surgery During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Macro-Politics: The Fractious History of the Physicians, Surgeons and Apothecaries

As hinted, the three recognized medical organizations were often locked in a struggle for control of medicine. Historian Jonathan Charles Goddard said that the political landscape of medicine was defined by "the ever-warring branches

Artists: Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin

Microcosm of London, Plate 020 - College of Physicians Meet (1808)

of medicine, the physicians, [where] the surgeons, and the apothecaries, maintained (or attempted to maintain) suitable professional chasms between each branch"1. Being the most 'learned' because of their required classical education, the physicians were usually on top. Throughout their history, the College of Physicians endeavored to maintain control of medicine in London, particularly by enforcing "their formal legal right to be the only occupational group able to prescribe internal medicines."2 A brief look at the history of their skirmishes with the other branches of medicine in the 17th century bears this out.

As early as 1604, the barber-surgeons company tried to acquire a new charter that would have allowed them to prescribe internal medicines and prohibited the physicians and apothecaries from practicing surgery. This effort failed.3 When the Society of Apothecaries was established in 1617, the physicians obtained a new charter as a defensive measure. "This Charter conferred on them the power to take proceedings against anyone who was not a member of the College [of Physicians] who administered 'internal medicines'."4 The barber-surgeons railed against this charter, saying it should not be confirmed.

In 1629, the surgeons obtained a charter which confirmed their role, "but the Physicians retaliated by obtaining an Order in Council in 1632 which prevented surgeons from performing any but minor operations except in the presence of a member of the College."5 The surgeons protested, resulting in the order being retracted by the King in 1635. The physicians returned in 1641, petitioning the House of Lords seeking a bill to confirm their rights, which was counter-petitioned by the surgeons seeking the right to give internal medicines.6

The playing field shifted with the establishment of the Commonwealth in 1649. The new government consulted the College of Physicians and Society of Apothecaries about how to deal with rampant illnesses which had plagued the army and navy since the disastrous expedition in Cadiz in 1625.7

Artists: Thomas Rowlandson and Augustus Charles Pugin

Microcosm of London, Plate 003 - Board Room of the Admiralty (1808)

"The new government was strongly opposed to monopolies, and where there was a need for physicians or for physic it disregarded the traditional naval claims of the Barber-Surgeons and went to those best able to advise it."8

With the first Dutch War in 1654, the Commonwealth created the Sick and Hurt Commission (also called the Sick and Hurt Board) to deal with ill and wounded soldiers and sailors more effectively than had occurred in the past. A physician was appointed to organize the effort and a variety of physicians served on this board during the Dutch Wars. A physician was also picked to accompany the fleet to the West Indies in 1654. "It was this attitude which gradually allowed the Society of Apothecaries to gain increasing control over the supply of sea-surgeons’ chests"9.

Historian Harold Cook explains that as late as 1687, the College of Physicians were still "especially concerned both to limit the influence of the other two London medical corporations, the Barber-Surgeons’ Company and the Society of Apothecaries, and to prevent their members and unlicensed empirics from practicing medicine without the supervision of the physicians."10

In addition to the protests of the apothecaries and surgeons, some of the physicians themselves complained

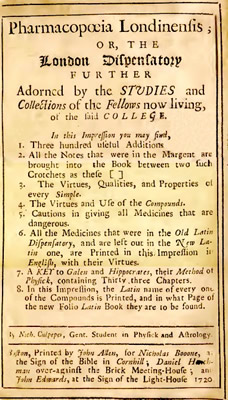

Nicholas Culpeper

about the College's attempts to keep the administration of internal medicines under their control. Nicholas Culpeper, a physician and herbalist practising in Spitalsfield, outside of the reach London's elite physicians, took the unthinkable step of translating the Latin Pharmacopoeia Londinenesis into English in 1651. The Pharmacopoeia was the official Royal College of Physician's instructional, outlining their recipes for compound medicines. This publication put the ability to concoct medicines into the hands of the people as well as the surgeons, many of whom could not read Latin very well. Culpeper added commentaries and indexes that explained which simple ingredients and compound medicines were most appropriate for the various health problems.

Nicholas Culpeper's Pharmacopoeia

Londinensis Title Page (1720)

Not surprisingly, Culpeper noted that the Physicians and Apothecaries "objected against my writing Books in English."11 Culpeper responded that there were Greek, French and Italian precedents for printing medicinal recipes in the popular language and he intended to continue to translate and publish medical books in English.

In the first edition of his book, he excoriated the College for trying to keep this information from the people.

How will you answer for the Lives of those poor people that have been lost, by your absconding Physick from them in their Mother Tongue? Are you a Colledg of Phisitians or no? Do you know What belongs to your Duty or not? Wherfore did K. Henry the Eighth give you your Charter to hide the Knowledg of Physick [medicine] from his Subjects yea, or no? Do you think you shal be called to an account for all you have done? I would have said for what you have left undone; Is not omission of good as great a sin as commission of evil?12

Culpeper broke the dam. Within a couple decades, other translations of the London Pharmacopoeia began to appear.13

Despite their efforts to diminish the importance and influence of surgeons, the physicians failed to eliminate them. "The physicians regarded surgeons and pharmacists as inferior, lacking classical education, but the surgeons and the barber-surgeons provided such necessary services that they continued to thrive."14

1 Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part I, Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Winter 1991, p. 206; 2,3 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, 1992, p. 217; 4,5 Jessie Dobson, Archivist to the Company & Robert Milnes Walker, Past Master, Barbers and Barber-Surgeons of London, 1979, p. 55; 6 Wear, p. 217; 7 See John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, pp.161-72 for a harrowing account of this expedition and its illnesses; 8,9 Keevil, p. 28; 10 Harold J Cook, "Practical Medicine and the British Armed Forces After the 'Glorious Revolution," Medical History, p. 9-10; 11 Nicholas Culpeper, "To the Reader", Pharmacopœia Londinesis, 1720, 2nd page; 12 Culpeper, “The Epistle Directory”, A Physical Directory, 1651, 2nd page; 13 See for example John Quincy's 1718 Pharmacopoeia Officinalis & Extemporanea: or, A Compleat English DISPENSATORY, In Four Parts; 14 Zachary B. Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail, 2002, p. 2

Macro-Politics: Medical Theories

A variety of theories appeared to explain the workings of health and medicine. Many of them were the results of discussions, arguments and schisms within the College of Physicians.

In the last three decades of the seventeenth century and during most of the eighteenth century there was a proliferation of new theories – iatrochemical [providing chemical solutions to disease and other medical ailments], iatromechanical [explaining physiological phenomena in mechanical terms], iatromathematical [using the laws of mathematics and mechanics to explain the functions of the human body] – but they did not improve life expectancy nor did they produce better cures than the old Galenic ones.1

Paracelsus - Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von

Hohenheim,

From the Wellcome Museum (1455)

While these theories sound intriguing and resulted in some interesting clashes between groups within the College, they had little impact on sea surgery. The most notable exception to this was the work of Swiss/German physician Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim - aka Paracelsus - in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. He advanced the idea of using chemical medicines rather than relying exclusively upon natural medicines. Sea surgeon John Woodall seized upon these medicines, including several in the first book for sea surgeons, the surgions mate. Likely as a result, chemical medicines were carried forward into the works of other authors who wrote for military and sea surgeons.

In addition to promoting chemical medicines, Paracelsus created an entirely new theory of medicine based on three elements: "a combustable element (sulphur) a fluid and changeable element (mercury) and a solid, permanent element (salt.)"2 He utterly rejected the prevailing classical theory created by Hippocrates, Galen and Celsus. In fact, his popular name was the combination of para and Celsus, indicating that his work was beyond that of Celsus. Just as Woodall had incorporated Paracelsus' chemical medicines, he included the Paracelsian concept of the three Elements near the end of his book, albeit only after he had explained many of the techniques espoused by the classical theory.

Woodall may have been a bit prescient. Unlike the chemical medicines themselves, the idea of the three Elements failed to be carried into other military medical works in any serious way. The cures espoused by other authors were firmly rooted in the classic medical dogma being espoused by the majority of the members of the College of Physicians - classical Galenic Humorism.

Galenic Humorism held that health and medicine was composed of four elements: blood, phlegm, black and yellow bile - and that illness was the result of either putrefaction (rotting) or imbalance of these four humors. Historian Andrew Wear explains that, "therapeutic procedures such as the use of bleeding, cupping, purging, the emphasis on diet and regimen (which was especially present in learned medicine) retained their popularity throughout the period"3 because they were used to balance or purge the 'bad' humors.

Author John Woodall

The military and sea surgeon's books from this time go to some pains to explain the Galenic teachings so that their readers could understand the theory and how it tied into their treatment plans. In the introduction to his 1639 edition, Woodall explained that the method of curing was divided into three parts: surgery ("the Handy part of healing"), diet ("without which neither wounds, apostumes, ulcerations, nor tumors... can well bee cured") and medicines ("a principall part of healing and curing of sores, diseases, and sicknesses").4 All three of these curative methods involved manipulation and modification of the bodily humors.

Woodall firmly grounds his comments in classical medicine, specifically mentioning Hippocrates and Galen when discussing the importance of diet. He quotes Galen in attempting to affirm the surgeon's need to be able to counsel the patient on diet and administer internal medicines. With regard to diet, Woodall explains, "I conceive him to bee no just and charitable judge, that denyeth this instrument, namely dyet, to belong to a Chirurgeon as well as to a Physician: for, that reason and experience both doe allow and approve thereof, as an unlimitable instrument, sine quibus esse nequit [without which it cannot be]."5

Military surgeon Thomas Brugis gives an even more detailed explanation of medicine while defining the ideas behind three different types of medical practitioners which existed in medicine.

The first

Author Thomas Brugis

group were the Empirics "who slight Reason, and only build upon use, they enquire only into the symptoms; they try medicines... or learn them tried from others ...or whatsoever they find in Books: then they use them by passing from like to like; either from disease to disease... or from remedy to remedy"6. These included both old school surgeons, who eschewed theory, and the serious (non-quack) unlicensed practitioners who used treatments that had worked based on their experiences or hand-me-down knowledge.

The second group he called the Methodics. "[T]hese mind neither [body] part affected, cause, age, time, region, faculties, habit [of body], nor custom of the sick, only the disease". The theory of treatment revolved around the notion that a disease produced a body that was "either bound or loose, or compound of both; the bound they loosened, and the loose they bound; in mixt they helpt what urged most and so they said the whole Art might be learnt in six months... To heal, is to remove what's strange, which is either extern[al] or intern[al]"7Rejeecting any concern for the patient, this group was not well reflected during the golden age of piracy.

The third group were the Dogmatics or Rationals. This method is composed of two parts: "Hygiene, which shews how to preserve health; and Therapeutic, which cures diseases."8

Hygiene was further broken down into six 'non-natural' things: air, motion (exercise), food, drink, sleep and passions (emotions).9 Proper hygiene resulted in good use and regulation of these six 'non-naturals'. The only non-intuitive one is air. This was included because the air the patient breathed was believed to have a direct impact on health. For example, marshy and boggy areas and sea air were all thought to produce unhealthy results, most likely due to their association with malaria (mal-AIR-ia) or scurvy.

The other part was therapy. "Therapeia teaches how to cure disease, by Diet, Pharmacy or Chirurgery."10 These were the same three methods of curing which Woodall mentioned.

1 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, 1992, p. 120-1; 2 "Paracelsus: Philosophy," wikipedia.com, gathered 4/7/15; 3 Wear, p. 121; 4,5 John Woodall, "The Preface", the surgions mate, 1639, 5th page; 6 Thomas Brugis, “To the Young Artist By way of Institution, Vade mecum, 1689, not paginated, 3rd page; 7 Brugis, 3rd-4th pages; 8 Brugis, 4th page; 9 Brugis, 15th - 21st pages; 10 Brugis, 4th page.