The Politics of Sea Surgery During the GAoP Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

The Politics of Sea Surgery During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Micro-Politics: The Importance of Sea Surgeons

Let us turn from the large-scale, land-based macro view of the politics surrounding the sea surgeon to the world of the sea-surgeon himself.

Ships were not used much in battle in the middle ages, rather functioning as transports

Artist: Frans Huys - 16th Century Galleys and Carracks in Battle (1561)

to get soldiers from England to the place where the battle was fought. So the first English surgeons at sea, were not really sea surgeons in the fullest sense; they were carried to the battlefield to treat the soldiers who were wounded during the fighting on land. Naval medicine historian John Keevil explains "the English traditional view was that a surgeon was only useful in battles: seamen were not fighting men and should not get wounded in the course of their proper duties: if soldiers were carried and a sea-battle ensued, the provision of surgeons was their concern."1

The Renaissance was a period of exploration by sea. By 1410, cannons and mounted hand guns were being put on ships.2 With ship-based warfare came an interest in ship-based surgeons. As far back as the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, surgeons were pressed into service of England. From this time forward there were "great demands for a supply of surgeons on board the ships."3

The first record of a structured sea-going medicinal service appears in the early 16th century. "[T]he Cotton MSS in the British Library dating from 1512 or 1513... lists the pay of the chief surgeon, of eight 'other surgions being most expert' and of more junior surgeons, who served in Howard's fleet against France."4 Nineteen ships with thirty-six surgeons, four master surgeons and a chief surgeon are listed in the Exchequer Accounts. Sir James Watt suggests that surgeons were only used when the country was engaged in wars during this period, which agrees with John Keevil's book. However, Watt says that it was a permenant situation by 1588 when "vice-admirals of counties were empowered to call on local barber surgeons' companies to provide surgeons for the fleet" for the battle with the Spanish Armada5 Keevil suggests that most surgeons during this period were personal surgeons recruited by the individual ship commanders rather than a formal naval dictum.6 Whatever the case, the Company of Barber Surgeons tasked with examining naval sea surgeons in 1606 to make sure they were competent, a definite step towards having naval surgeons a part of the formal structure.7

While some surgeons were employed at sea during wartime or for particular sea-ventures, they were not an integral part of a naval vessel's complement until the 17th century. The motivating event for their inclusion in English ships was the disastrous attack on Cadiz, Spain by King Charles I in 1625 where sickness, not battle wounds, had debilitated the English Fleet.

Artist: Francisco de Zurbarán - The 1625 Cadiz Expedition (1634-5)

"On October 26 many of the soldiers in the fort began to report sick; the fleet was mutinous, the soldiers drunk, and Cadiz appeared impregnable."8 The sickness increased, resulting in the leaders debating what should be done. An estimate of ill men was requested of the Fleet ships on November 1st. Of the six ships reporting, nearly 25% of the men were sick.9 On November 9th, Sir Edward Cecil, captaining the Anne Royal, wrote that soldiers "fall sick everie daie, and so doe our Sea Men so fast, that their Officers complaine, they have not able men enough sufficient for their watches; in most of the Fleete, and in the Convertine of the Kinges, Captain Porter tells mee, he is not able to make 15 in a watch, to trimme the sailes"10. These ships limped back to England with most of their contingent ill. "[O]f two hundred and fifty seamen in the Swiftsure, only sixteen men in one watch and seventeen in the other remained to control the ship"11. John Keevil believes that the illness was typhus which had been contracted by the landed soldiers who then spread the sickness when they returned to the ship.12

In 1629, King Charles I renewed the Company of Barber Surgeons charter, directing that "all the English ships calling at English ports [are] to have a surgeon on board. The king ordered the Barber-Surgeons’ Company [of London] to get 97 trained Surgeons to fill the ships which had not surgeons, for when the law came into force"13. He further ordered anyone acting as a sea surgeon must have their instruments and medicines examined by the Barber-Surgeon's company.

It was not quite that simple to find so many surgeons wanting to go to sea, however.

Artist: Howard Pyle - A Press Gang (1882)

Charles felt compelled to write to the Barber Surgeon's Company that "Our will and pleasure is, and wee doe hereby authorize and require you to imprest from tyme to tyme such and soe many sufficient and experienced Chirurgeons for our service as you shall have directions for from us notwithstanding any such protection whatsoever"14. However, the Company felt that it was not the King's place to demand they impress surgeons and they do not appear to have taken any steps to do so, fearing "some penalty if they tried to secure more surgeons by force"15.

Yet the problem of filling the ships remained. In 1635 the Navy Office to the Board of Admiralty issued a letter directing,

The Fleet now drawing near hand ready to goe to Sea we have according to the ancient custome given orders to the Masters and Wardens of Barber Chirurgeons' Hall, to press Chyrurgeons for all the Ships of the first Fleet and have given them charge to cause them to appeare before us att the Meeting house in Mincing Lane, on fryday in the afternoon the 1st of Aprill, for the Vice Admirall and Rere Admirall to be satisfied of their Sufficiency, according to the directions received from your Lo'ps [lordships].16

Supplying surgeons to ships was to be a continual problem for the Company and the Navy. During the second Dutch war, the Privy Council was again having trouble finding qualified surgeons and mates for their naval vessels in 1665, so they relaxed the requirement for ship's surgeons and mates, allowing them to join the Company of Barber Surgeons as foreign brothers17. This practically removed any control the Company had over these men. The Company maintained its monopoly on the appointment of Royal Naval surgeons, but its influence was on the wane and merchant-ship surgeons began to avoid joining the London company in favor of the outlying provincial companies.18 In an attempt to maintain its position, the Company claimed national authority over the surgeons in 1710, although it had no legal basis for doing so.19

1 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume I – 1200-1649, 1957, p. 20; 2 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 25; 3 Jessie Dobson & Robert Milnes Walker, Barbers and Barber-Surgeons of London, p. 47; 4 Sir James Watt, “The Naval Connection”, The Company of Barbers and Surgeons, Ian Burn, ed., 2000, p. 171; 5 Watt, p. 172; 6 See Watt, p. 172 & Keevil, p. 65-6; 7 Dobson & Walker, p. 48; 8 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 165; 9 Based on a chart found in Keevil, Volume 1, p. 166; 10 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 167; 11 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 168; 12 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 173; ,13 Dobson & Walker, p. 48; 14 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 187; 15 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 188; 16 Dobson & Walker, p. 48; 18 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, p. 49; 18 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 28; 19 Keevil, Vol II, p. 262

Micro-Politics: How Sea Surgeons Came to Be Able to Prescribe Medicine

As explained in the section Macro-Politics: The Fractious History of the Physicians, Surgeons and Apothecaries,

Illness Shipboard, From the Death of Sir Hugh Willoughby (1554)

the physicians jealously guarded their ability to prescribe internal medicines from the surgeons, particularly in London. This was problematic given that many of the health problems which occurred on long voyages to foreign climes during the 16th and 17th centuries were illness, not the wounds that actually fell under the purview of the surgeons. Scurvy, typhus, dysentery, malaria, yellow fever and similar tropical illnesses plagued the navy and decimated many of their sea voyages. These were internal health problems, requiring internal remedies.

At the same time, the physicians showed little interest in accompanying extended naval and exploratory voyages. In 1588, the Privy Council, advisors to the King, sent a letter to the College of Physicians stating "that whereas a dysease and sicknes began to encrease in her Majesties Navye, for remedie of the dyseased and for staie of further contagion their Lordships thought meet that some lerned and skillfull phisicions should presently be sent thether"1, specifically requesting that two physicians be supplied to the Navy. Keevil explains that whomever went, they stayed less than a year, adding that there was "no evidence of any other physicians being employed in the queen's ships."2

The men who did accompany the Navy during this period, particularly when they were going to battle, were the surgeons. They witnessed the devastating effects of tropical and long-sea voyage illnesses but could legally do nothing to solve the problem. When they sailed home, they returned "to a metropolis in which physicians and surgeons were professionally divided and where... the Physicians in their court of summary jurisdiction were regularly trying any surgeon who gave internal medicines."3 As Keevil so aptly summarizes it,

Surgeons were by tradition only carried if men were likely to be wounded, and were still associated with soldiers, not with mariners. As for the treatment of diseases, surgeons were forbidden by law to meddle with such things, physicians did not go to sea, and this was a matter for common sense and the commanding officer.4

This all came to a head during the 1625 attack on Cadiz, the goal of which was completely undermined by what was likely typhus as noted previously. While the attack was an absolute disaster for England, it was a watershed moment for English sea surgeons. In July of 1626, a group

Image Artist: Ivan Aivazovsky

Loading Provisions Off the Crimean Coast (1876)

of newly press-ganged sea surgeons petitioned the Council of War "that if there were to be no physicians or apothecaries on board, the sea-surgeons might have an allowance to provide the necessary 'physic and surgery'."5 The Privy Council agreed, ordering "‘that for a supplie of phisicall drugges and medicaments to be provided for the surgions appointed to goe in this next Fleete'... with 'all such monyes as shalbe allowed to any chirurgian in his [the king's] service by way of imprest money towardes the furnishing of his chest with chirurgery, medicines and instrumentes’"6.

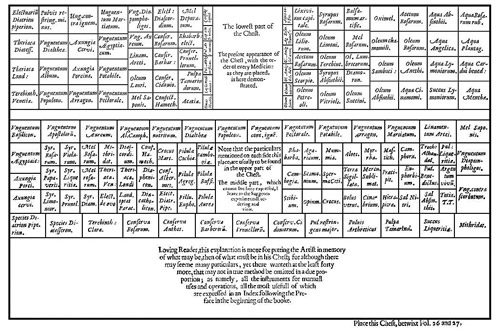

The idea behind this system was that the surgeons would be allowed a certain amount of money - the free money - to buy initial supplies. Thus was combined with imprest money which was to furnish and replenish supplies in the chest when used. The amount paid for the chest supplied each surgeon depended on the type of ship on which he was stationed, which can be seen in the chart at right. (For an explanation of the different types of ships used during the golden age of piracy, see this article.) This money was paid directly to the Company of Barber Surgeons, who were to furnish the instrument and medicine chests.

Not having any experience with supplying medicine chests, the Company of Barber Surgeons turned to sea surgeon John Woodall. Woodall had begun specifying the contents of and supplying medicine chests to the East India Company some time after his appointment to

Layout of the Medicine Chest, From John Woodall's book the surgions mate (1639)

the post of Surgeon General to the company in 1612 and before the publication of his book the surgions mate in 1617. Nearly half of his book was devoted to explaining the uses of the internal and external medicines. Woodall even included a chart of how it was to be laid out in the 1639 edition of his book, which was likely intended to be pasted in the lid of his medicine chest for reference.7

Woodall may have modeled his system for the East India Company on that of the United Netherlands East India Company which was implemented around 1602. "Like the English sea-surgeons, [the Dutch surgeons] were strictly prohibited from treating internal diseases when at home, yet they were required to do so on entering the Company's service: they were supplied with medicines in their chests, and had to use them when smallpox, scurvy, typhus, malaria or dysentery attacked a ship or factory."8

1 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume I – 1200-1649, 1957, p. 69; 2 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 70; 3 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 123; 4 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 70; 5,6 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 176; 7 Rory W. McCreadie, The Barber Surgeon's Mate of the 16th and 17th Century, 2002, p. 35; 8 Keevil, Volume 1, p. 152

Micro-Politics: Sea Surgeons On Being Able to Prescribe Internal Medicines

Most diligent surgeons had an opinion about their inability to prescribe medicines. This inability was particularly problematic for sea surgeons, who, as we have seen, encountered a variety of different illnesses requiring internal treatment and yet had no one whom they could consult and who could prescribe medicines. Such frustrations were sometimes expressed in their books. As early as the late 16th century, sea and military surgeon William Clowes said "where the learned physician is not to be had, be it either by sea or land, far or near, I will then use all honest and lawful means, both in physic and surgery, to the uttermost of my knowledge and skill, before I will any way permit and suffer my patient to perish for want of all help."1

Writing over a hundred years later, John Woodall was somewhat circumspect about the use of medicines by sea surgeons in the first edition of his book, explaining that the surgeon's mate must learn his trade by

Artist: Jan van der Straet - Taking Internal Medicines (1600)

observing the whole passages of the diseased people considering both when they began to bee sicke, as neere as he can, the causes thereof, what hath beene applied either inwardly or outwardly, what operation the medicine had, and so of every diseased person, and every medicine given, and to keepe a Jornall in writing of the daily passages of the voyage in that kinde, and that as well of the unsuccessive applications, as of the successive, he shall finde great benefit in both: Likewise what alterations of operations he findeth in each medicine, and what medicines keepe their force longest, & what perish soonest. Also what variety the climate causeth, of the Doses as well of the laxative as opiate Medicines.2

By the publication of his second book Viaticum in 1628, Woodall noted that "His Highness hath... beene well pleased to give authoritie unto the Masters and Governors of our Societie [the Company of Barber Surgeons], for... the making, compounding, fitting, and ordering of all the Medicines, as well Physicall as Chirurgicall"3. In the 1639 edition of his book, Woodall transformed into an outspoken advocate for allowing surgeons to use internal medicines, likely emboldened by Privy Council's blessings, the King's revision of the Barber Surgeon Company's charter and the Navy's reliance on him to supply them with internal medicines for their sea surgeons. In his Preface, Woodall explained, "Each man will conceive that medicine is a principall part of healing and curing of sores, diseases, and sicknesses: for who is hee that can cure a wound, a tumor, an ulcer, yea, but an ague with his hand only, without fitting medicines? Surely no man"4.

Woodall goes on to argue that military surgeons

From Krueterbuch Kunstliche Counterfeytunge

der Baume (1569)

must not bee forbidden lawfull practice, otherwise how shall he well performe his scope of healing, when hee is either in Ship, in Campe, or but any where in the Countrey, where Physicians either are not at hand, or will not come? As when and where contagious diseases happen, namely, the small and great pox, or the pestilence, &c. Now here in all conscious the Surgeon is to bee admitted to shew his utmost skill for healing mens infirmities, without danger of any Law, if hee be a man lawfully called, as aforesaid, to the exercise thereof: otherwise it were very unreasonable that the Surgeon alone should be pressed out [by the press gangs] to the healing of his Majesties subjects, where no Physician nor Apothecary is admitted to advise, assist or direct him, and yet to practice should bee held unlawfull for him, when hee performeth his best in any action or part of healing for his patients good.5

Sea surgeon John Moyle, writing in 1703, had a similar argument, although he was not quite as bold in stating it as Woodall had been. Moyle said,

Reason dictates, and Necessity often requires, and the Practice of the Ancient exemplifies a farther Latitude [in prescribing medicines]. That is, (the Physician being lacking) the Chirurgion may rightfully exhibit to his Patient such internal Means [medicines] as he knows will conduce to the effecting of his Chirurgical Cures. Howbeit, in dangers Affects, such as Pluritic Impostumes and Penetrating Wounds; although the Chirurgion may know well, yet if the Physician can be had, it is more safe to take his Advice, which will render your Endeavours the more warrantable.6

Keep in mind that when Moyle wrote this, the sea surgeon had been allowed to prescribe internal medicines on ships for seventy-five years!

John Moyle

One thing had changed, however. Physicians had been regularly assigned to the flag ship in the English Naval Fleets during wartime beginning in 1691, which gave naval sea surgeons limited access to their advice. This access to physicians is reflected throughout Moyle's book. He cautiously provides recipes for internal medicines and procedures that were legally reserved to the physician, noting that while something is usually the physician's responsibility, it becomes the surgeon's if there is no physician handy. He says this when talking about treating an edematous tumor7, a schyrrus8 (an inflammation, believed to be be caused by black bile), hydropsia9, timpanites10, cancer11, a puncture wound in the abdomen12 and a penetrating wound of the thorax13.

At the same time, Moyle seems to recognize the limits of the sea surgeon's training and the importance of the physician's province. When discussing the use of internal medicines to treat tumors, he recommends that "as to these inward Means, ‘tis best to take the Physician’s Advice."14 He gives similar advice when discussing the treatment of scrofulous [tuberculosis-caused or tuberculosis-like] tumors and ulcers15, wounds in the body of an unhealthy patient16 as well as those exhibiting cacochymia, or unhealthy/unbalanced humors17.

Of course, it must be recognized that many surgeons who went to sea did not have sufficient knowledge to perform the duties of a physician. Sea surgeon Thomas Aubrey states this several times in his surgical book on caring for slaves carried on ships. Following his presentation of a case study where a ship's surgeon had treated a man with erysipelas (an acute skin inflammation) with emetic tartar (antimonium potassium tartrate - a toxic drug), Aubrey comments that "you'll imagine what a Number of poor Wretches lose their Lives on this dangerous Coast; merely thro' Ignorance of their Surgeons." He goes on to advise that "it highly behoveth all young Surgeons who have a Mind to frequent this Coast [Africa], to endeavour to qualify themselves very well, before they undertake such a Charge, otherwise they ought to be no more esteemed, than as willful Murtherers [murderers]."18

Aubrey gives many such caustic analyses of surgeons who do not understand medicines or the humoral arts which were normally reserved to physicians. He says surgeons who misunderstand the treatment of a putrid fever by failing to bleed the patient are ignorant19,

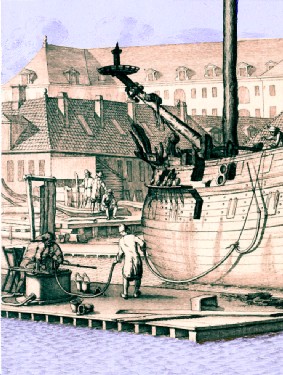

Ship in Dry Dock (17th century)

those who mistake putrid fevers for colds "destroy the Sick"20, surgeons who allow an inflammation of the lungs to form pus or degenerate into an eympyema are either negligent or ignorant21 and those facing a patient with yaws (a bacteria-based skin infection), "commonly [mis]take this Flux for a simple Diarrhœa, and so vomit them with Ipecacoanha, and give them Astringents, which is only throwing away their Medicine".22

Aubrey's comments have more to do with the ignorance of sea surgeons than with their inability or unwillingness to consult with a physician, however. Recall that John Woodall advises his potential sea surgeon readers "to read much, I mean in Chirurgery and Phisicke, and well to consider & beare in minde what he reades"23. While such studiousness might have helped to address Aubrey's concerns, historian John Kirkup points out that while Woodall's advice "might well have been appropriate to men who devoted their lives to service at sea, ...[it] could have had little influence on surgeons sent to the king's ships, often unwillingly [because they were pressed into service] and [intended] only to remain in them for a few months."24 When such pressed men returned to shore, any acquired knowledge of internal medicines would not serve them well because the College of Physicians prosecuted land-based surgeons caught practicing physic.

1 William Clowes, Selected Writings of William Clowes, 1948, p. 84-5; 2 John Woodall, "The Office and dutie of the Surgions Mate", the surgions mate, 1617, not paginated, 3rd page; 3 John Woodall, "The Preface", Woodalls Viaticum, 1628, not paginated, 3rd page; 4 John Woodall, "Preface", the surgions mate, 1639, not paginated, 5th & 6th pages; 5 Woodall, "Preface",1639, not paginated, 8th page; 6 John Moyle, The Experienced Chirurgion, 1703, pp. 1-2; 7 Moyle, p. 18; 8 Moyle, p. 23; 9 Moyle, p. 25-6; 10 Moyle, p. 32; 11 Moyle, p. 246; 12 Moyle, p. 247; 13 Moyle, p. 251; 14 Moyle, p. 19; 15 Moyle, p. 47; 16 Moyle, p. 230; 16 Moyle, p. 235; 18 Thomas Aubrey,The Sea-Surgeon or the Guinea Man’s Vadé Mecum. 1729, p. 68; 19 Aubrey, p. 29; 20 Aubrey, p. 40; 21 Aubrey, p. 54; 22 Aubrey, p. 118; 23 John Woodall, "The Office and Dutie of the Surgions Mate", the surgions mate, 1617, p. 4; 24 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume I – 1200-1649, 1957, p. 218