The Politics of Sea Surgery During the GAoP Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

The Politics of Sea Surgery During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 1

"With the exceptions of those who were lucky enough to find themselves at the top of the medical tree, being Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians or Company of Surgeons, medical men were not well endowed with wealth, position or social status.

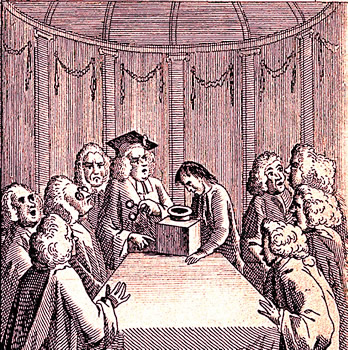

Physicians Argue Treatment Theories for Syphilis While the

Patient Expires,

From A Harlot's Progress, Plate 5, By William Hogarth (1732)

It could hardly even be said that they were members of a medical profession, as the ever-warring branches of medicine, the physicians, the surgeons, and the apothecaries, maintained (or attempted to maintain) suitable professional chasms between each branch... The naval surgeons thus found himself at the very bottom of this healing hierarchy, his position was considered to be the lowest of medical employment and generally as a situation of last resort. He consequently found himself well positioned to receive the contempt of his (slightly) better placed ‘landlubber’ colleagues and to be ignored by his medical and nautical overseers.” (Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part I, Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Winter 1991, p. 206)

Where there are people, there are politics. Some of them are formal, being enshrined in the government and formal organizations of society while others are informal being a part of every day life. Sea surgeons were exposed to all sorts of political influences: the decrees of the crown, the mandates of their Company, incursions into their realm by other guilds and societies, the dictates of the Navy and even pressures from their ship's captain. This article looks at the various elements of both the more formal, macro-political and less formal, micro-political aspects of sea surgery.

The formal, macro-political aspects of medicine and how they impacted surgery during the golden age of piracy are first examined, beginning with the history, influences and interplay of the government and the three primary medical branches in England: physicians, surgeons and apothecaries.

Artist: Jacob Knyff

English and Dutch Ships Taking on Stores (1673)

The medical theories of the period impacted all the formal medical practitioners, so they are briefly described. A great deal of infighting existed within the Barber-Surgeon's Company which directly impacted sea surgeons. This is followed with a look at how some surgeons attempted to make their profession more 'learned' or respectable to mirror the training of the physicians. Since surgeons were primarily focused on the practical aspects of medicine, the debate over the importance of practical versus theoretical elements is examined. The formal, macro-political elements of the surgeon's world concludes with a look at how the British Navy viewed the practise of surgery leading up to this time.

The micro-environment of the ship defined the sea surgeon's informal, micro-political environment. Sea surgeons were in the fairly unique position of being the only medical practitioner on most ships, requiring them to specify a patient's diet and to prescribe internal medicines, something that their land-based brethren could not do. As a result, an on-going tug-of-war over who specified and controlled the dispensing of the medicines occurred. With a vested interest in the most appropriate and easy-to-use medicines, the Navy also weighed in on medicine specification. A sea surgeon's position in the Navy was that of a warrant officer, which is also discussed. More important than the sea surgeon's title was his relationship to the captain. This is examined for both the naval and merchant marine environments. The most uncertain informal political environment on a ship was that found in pirate vessels where both the captain and crew could impact the ship's surgeon situation.

Let's look in detail at each of these politically-tinged areas of the sea surgeon's life.

Macro-Politics: Politicians, Physicians, Surgeons Apothecaries and Others

In the broadest sense, pressure on sea surgeons started with the king. He granted and renewed

Royal College of Physicians, London. Architect

Roger Hooke, Wellcome Collection (17thc.)

the charters which established the College of Surgeons, the Barber-Surgeons' Company and the Society of Apothecaries. From their creation up through the golden age of piracy, these three groups ruled the formal aspects of medicine in England. They allied, fought and plotted with and against one another in an effort to gather or maintain the power required to sway the political course of medicine in their country.

The first medical group to be given sovereign recognition was the physicians. "A small group of physicians led by the scholar Thomas Linacre petitioned King Henry VIII to establish a college of physicians on 23 September 1518. An Act of Parliament extended its powers from London to the whole of England in 1523."1 Originally called the College of Physicians, it became known as the 'Royal' College of Physicians during the 17th century.

The surgeons were the first practitioners to form an exclusively medical guild in England. The first lay surgeons were trained by monks in the thirteenth century. The monks trained the barbers who shaved their tonsures and beards to perform surgical operations. "The barber... worked under the guidance of the former priestly surgeon, and generally did so without pay 'to gayne knowleche of aylimentes and theyr trew curis'."2

Barbers formed guilds before 1300 which "took on apprentices, taught them with lectures, dissections, and practical demonstrations, examined them and then licensed them to practise in the city of guild. In 1462 the guild was incorporated and henceforth known as a company."3

Society of Apothecaries Shield on Pill Tile, Wellcome Collection (c. 1660)

While they may have been first to establish themselves as a guild, the surgeons were the second of the three formal medical groups to receive sanction from the King. An Act of Parliament passed in 1540 established the Company of Barbers and Surgeons.

The last formally recognized group of medical men were the apothecaries (or druggists). They were originally part of the Pepperers Guild (in reference to the spice pepper), the first iteration of which predates that of the surgeon's guild, having been mentioned in writings from around 1100. The Ancient Guild of Pepperers was re-established as a new guild in 1345 in London, eventually becoming known as the Company of Grocers in 1376.4 Apothecaries found their place among the grocers.

The relationship between the apothecary members of the grocer's guild and the grocers was contentious, resulting in the apothecaries forming their own distinct section within the guild.5 They formally broke from the grocers guild in 1617 with the formation of The Society of Apothecaries under charter from King James I.6

1 "History of the RCP", Royal College of Physicians Website, https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/about-rcp/our-history, gathered 2/9/17; 3 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume I – 1200-1649, 1957, p. 13; 3 Elizabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments, 1979, p. 4; 4 "The historic timeline of the grocers' company over more than eight centuries". Grocer's Hall website, http://grocershall.co.uk/the-company/history/, gathered 2/9/17; 5 Bennion, p. 6-7; 6 Jessie Dobson, Archivist to the Company & Robert Milnes Walker, Past Master, Barbers and Barber-Surgeons of London, 1979, p. 56 & Bennion, p. 7;

Macro-Politics: Politicians, Physicians, Surgeons and Apothecaries - Interactions

Like many elements of English society from this period, there were palpably defined strata among the medical organizations. Much of this was an extension of the role of each company.

At the top were the physicians, "whose job was to diagnose, and provide attendance and advice. Members of a liberal profession, founded upon a university education, physicians were expected to have a gentlemanly bearing to match that of their wealthy patients."1 Much of their work was theoretical, befitting their multi-year university studies of the classic medical writers such as Hippocrates, Galen of Pergamon and Aulus Cornelius Celsus. Entrance into the Society could only be obtained following examination.

Physicians Debating at the Royal College in London.

From The Devil Upon Two Sticks, By William Combe (1771)

2 Their elite status was recognized by the other medical men of the period; sea surgeon John Woodall explained that "the more learned sort [of medical artists] are justly stiled by the title of Physicians"3.

Physicians could diagnose illnesses, prescribe medicines and, for most of the period up to and including the golden age of piracy, oversee the functions of the other two official branches of medicine in England - the surgeons and apothecaries. They did this by debating the cause of diseases, often concluding that the classical works they had studied held the answers rather than proving it to themselves through practical experimentation. While their control over the medical trade in London was strong, it weakened outside of the metropolis, where "the presence of university educated physicians was haphazard."4 It had limited direct impact on the sea surgeons, who were far away from the lofty debates held in London, although they largely carried the classical philosophy with them as we shall see.

Seen through the modern historical lens, the role of the physician is sometimes denigrated. Modern historian Joan Druett says "Physicians spent most of their time debating, writing, and preserving ancient dogma."5 JC de Villiers points out that "Disease continued unabated despite learned dissertations and speculations about the causation [by physicians]."6 Historian Andrew Wear takes a little more measured approach, explaining that,

The College had tended to have bad press. Modern historians have often emphasised its limited membership, its authoritarian obscurantism, its persecution of empirics [those relying exclusively on observation and experimentation] and poor wise women, its hostility to new ideas, and, of course, its being on the losing side in the debate between the ancients and the moderns in the later seventeenth century.7

Second, yet lower, in prestige were the surgeons and their Company. They were legally restricted to treating external complaints, particularly in London, being allowed to employ only external or topical medicines and even then (theoretically) only under the eye of the physician.8

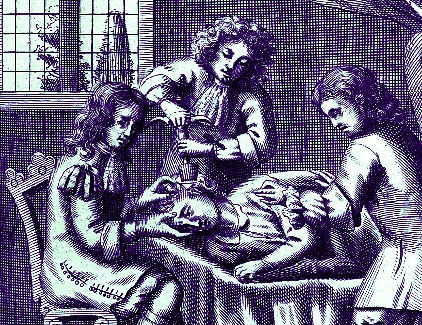

A Surgeon and His Assistants Trephining a Patient, From A Complete

Discourse

of Wounds,

By John Brown, From The Wellcome Collection (1678)

Much of their lack of prestige stemmed from the practical nature of their work. Roy Porter notes that the surgeon's art was considered "a craft not a science, involving the ‘hand’ not the ‘head’; and it was a skill taught by apprenticeship. His job... was to treat external complaints (boils, wounds, etc.), to set bones and perform simple operations."9 Surgeons could be approved to practice their art following a seven year apprenticeship and examination by the Company.10 Many land-based surgeons then became itinerant surgeons, serving the populace with many eventually turning to sea surgery. This seven year apprenticeship was often shortened by necessity for sea surgeons as we shall see.

The surgeons tried to overturn their inability to prescribe internal medicines repeatedly, although, for the most part, they failed to succeed in London due to the impact of the College of Physicians' royal charter on policy.11 As mentioned, the physicians influence was diminished outside of London, allowing other branches to become more involved in prescribing internal medicines, particularly before 1700. Porter explains, "In small towns... there would be just one single practitioner who would turn his hand to all branches of healing. By the eighteenth century the name ‘surgeon-apothecary’ was the commonest title given to the country or small-town practitioner."12

This was similar to the situation at sea where physicians and apothecaries were rarely found. The role of the apothecary involved aspects that could not be practically performed at sea such as gathering and processing herbs and plants. Physicians might have served in a useful capacity at sea, and occasionally did so, particularly in the Royal Navy. However, "Service at sea offered few attractions to the more

;Artist: Nicolaas Baur - Ship's Council of War (1848)

lordly physician whose knowledge and skills, even given the limitations in medical knowledge of the time, might have been more useful."13 As a result, the sea surgeons were typically recognized as the sole practitioner of all the branches of medicine on a ship.

The hands-on nature of the surgeon's practice meant that he was more involved with the patient than either the physicians or the apothecaries. Sea surgeon historian John Keevil notes that this created a 'great gulf' "[b]etween the average practitioner and the distinguished academic world"14 which contributed to the physician's disdain for their surgical brethren.

Even so, the surgeons recognized the superiority of the physicians, at least in a social, if not a practical, sense. While sea surgeon Woodall admitted that the physicians were 'justly' recognized as being learned, he also added that "the more experienced sort [of medical practitioner] are called Chirurgions, or Surgeons; by means whereof, sometimes there hath growne difference and offence"15. This is a rather back-handed complement, pointing out the physicians' lack of practical skills. However, he goes on to recommend that his readers (typically surgeons in training) should avoid the controversy "and that they give the Physician his due honour and precedence, comparisons being odious and unmannerly amongst good men."16

The apothecaries' status in the medical hierarchy was somewhat less definite around the golden age of piracy, although it appears to have been beneath that of the surgeons who had a certain amount

of independence due to their rather unique skills. Apothecaries, like the physicians, had only limited contact with the patient. Their Charter "defined and set limits to their power. Describing the craft as a Mystery, they said that the office of those enrolled in it was to

Artist: Michel-Charles Coquelet-Souville

Apothecary Claude Morelot in his

Pharmacy (1751)

make up and prepare physic for the sick, in obedience to the prescriptions and directions given to them

by the physicians."17 Historian Roy Porter explains it succinctly: "The physician prescribed; the apothecary dispensed."18 This resulted in their being subjugated to the physician.

Like the surgeon, the apothecary's training was

by apprenticeship. In order to be effective, "they were required to have a skilled knowledge of plants and herbs, roots and drugs, and to be qualified in the theory and practice of chemistry."19 In this way, the apothecaries were "hands-on" practitioners like the surgeons, and thus of a lower status than the physicians.

Apothecaries had to learn a variety of tasks to master their trade. They must first be able to recognize the plants used to make up their medicines which were referred to as 'simples'. They were then used to create compound medicines which were specific, prescribed combinations of simples. The recipes for these compounds were laid out in Latin in The London Pharmacopoeia by the College of Surgeons. Part of the practice their trade required the apothecary to regularly go "asimpling" or gathering the herbs in the field. The fresh plants were then processed by drying, crushing, powdering, heating and/or distilling, among other processes.

Patients sometimes cut out the middlemen, elevating the apothecary to the role of practitioner, particularly outside of London where the reach of the Society of Physicians was weaker. Here, "the apothecary increasingly acted the physician’s part. Indeed the surgeon and apothecary also overlapped."20

This overlap between apothecary and surgeon was not always viewed favorably by the surgeons. Sea surgeon Hugh Ryder noted that it was "a common thing for Apothecaries to practise Surgery, but with what success"21? He detailed a case study where an apothecary had spent several months trying to cure a man with a fistula

not at all knowing what he was about, having used, as the Patient afterwards informed me, at least forty different sorts of Medicine, as Waters, Oyntments, &c. a sufficient argument of his unsteady ignorance. Once or twice, by Mercurial means (against his [the patient's] will as he prefest) raised a Salivation on him, had sometimes with his Knife made incisions, an sufficiently teaz'd him, at length told him, he had done with him, for he was cured and well; but the Gentleman being alarm'd by some pain he felt there, was advised by a friend of his to shew it to me22.

No description of the medical firmament in London is truly complete without mentioning the unofficial, mostly unlicensed people who practised medicine. These included "the Bonesetters, the Herbalists, the Midwives, and of course, the vast legion of Quacks."23

Artist: Cornelis Pietersz Bega

Quack Selling Patent Medicines in the

Village Market, (1650s)

Although much of the focus in modern stories is on the quacks, many of the people in this group served important and legitimate purposes. They learned their trade through an informal sort of apprenticeship and practice. "Some practiced full-time, others occasionally; some for money, others out of charity; some were licensed, most were tolerated, a few were prosecuted."24

Many of the quacks were unscrupulous shysters, "learned in the essentials of motive and behavior, assessing brilliantly the limits of public credulity".25 However, even some of these same quacks had a place, providing relief to those who could not afford the services of a barber-surgeon, physician or apothecary. Their patent medicinals were often alcohol-based, producing a feeling of relief from health problems, albeit a temporary one. In addition, although it was not yet understood, the effect of medicines as a placebo cannot be completely overlooked.

In some cases, these 'unlicensed' cures were actually more effective than those recommended by the sanctioned medical groups. In the cure of scabies, the physicians believed the problem to be an imbalance of the humors, so they bled patients and gave them ineffectual medicines including "peppermint water, fennel water, corn-poppy blossoms and sulphuric acid"26. None of these things removed the problem of 'the itch'. However, in early 18th century Pennsylvania, a 'widow Read' advertised the sale of "a Gallypot containing an Ounce; which is sufficient to remove the most inveterate Itch, and render the Skin clear and smooth" which, like other quack remedies for the itch contained sulfur, an effective remedy.27

Naturally, the quacks and unlicensed practitioners were universally condemned for their work by the three official branches of medicine in London.28 Even the somewhat more legitimate bonesetters and self-proclaimed unlicensed 'specialists' performing particular operations were looked upon with suspicion by the surgeons. So, while they might be able to make a fairly effective living selling their patent nostrums and treatments, the status of this group of practitioners generally remained very low.

1 Roy Porter, "The Patient in England, c. 1660-c. 1800", Medicine in Society, edited by Andrew Wear, 1992, p. 92; 2 Wear, p. 27; 3 John Woodall, "Preface" the surgions mate, 1639, unpaginated 5th page of the Preface; 4 Porter, p. 92; 5 Joan Druett, Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail, 2000, p. 12; 6 Jacquez Charl de Villiers, "The Dutch East India Company, scurvy and the victualling station at the Cape," Society of African Medical Journal, February 2006, p. 107; 7 Andrew Wear, Knowledge & Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, p. 35-6; 8 Leonard A.G. Strong, Dr. Quicksilver, 1660-1742; The Life and Times of Thomas Dover, M.D., 1955, p. 66 & Porter, p. 92-3; 9 Porter, p. 93; 10 Wear, p. 27; 11 Wear, p. 217; 12 Porter, p. 93; 13 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, 2011, p. 39; 14 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, 1958, p. 165; 15,16 Woodall, unpaginated 5th page of the Preface; 17 Strong, p. 63; 18 Porter, p. 93; 19 Strong, p. 63; 20 Porter, p. 93; 21 Hugh Ryder, New Practical Observations in Surgery Containing Divers Remarkable Cases and Cures, 1685, p. 28; 22 Ryder, p. 26-7; 23 Strong, p. 66; 24 Porter, p. 93; 25 Strong, p. 66; 26 Guy Williams, The Age of Agony, 1986, p. 197; 27 Williams, p. 198; 28 Weinberger, p. 235