Cereal Grains in Sailors Accounts Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Animal Products in Sailor Accounts During the GAoP, Page 2

Dairy

Dairy products don't usually rate a lot of discussion as a group in the period sources, although there are a few authors who discuss them. Modern historian Joan Thirsk notes that dairy was felt to be

.jpg)

Photo: Emilio Gómez Fernández

Diary Cows in Riotuerto (Cantabria, Spain)

food for the poor in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, likely because it was so easy to procure. Dairy started to become more fashionable in the second half of the sixteenth century when hard cheese and butter garnered interest among the more elite households.1 Thirsk notes the increasing industrialization of dairy farming through the seventeenth century increased interest as men began to become involved in an area that had largely been handled by women. "The old prejudice against cheese was evidently fading, judging by [John] Houghton's clear statement [in 1681] that it was a nourishing food, kept well, and could be carried to most parts of the world without damage."2 The navy's reliance on it as a standard food provided at sea testifies to that last comment.

Early seventeenth century author Gervase Markham talks about dairy in general terms in his book The English House-wife, first published in 1615. His title affirms the idea that dairy was primarily the domain of the woman in charge of an English household at that time. Markham opines that the cattle used "must be Kine [cows - note that the word cow refers specifically to female cattle] of the best choice & breed that our English House-wife can possibly attaine unto, as of big bone, faire shape, right bred, and deepe [full] of milke, gentle, and kindely."3

Markham goes on to detail each of his points in more detail, although not all of them are relevant to this discussion. With regard to the shape of the cow, he advises, "shee must have all the signes of plenty of milke, as a

Gervase Markham, From The Perfect Horseman (1655)

crumpled horne, a thinne necke, a hairy dewlappe, and a very large udder, with foure teates, long, thicke, and sharpe at the ends, for the most part either all white, of what colors soever the Cow be; or at least the fore part thereof, and if it be well haird before and behinde, and smooth in the bottome, it is a good signe also."4 He adds that milk cows can be of a variety of breeds, although they should not be a mixed breed. He even recommends that when purchasing cattle, the dairy woman "must looke diligently to the goodnes & fertility of the soile wherein you live, & by all meanes buy no Kine from a place that is more fruitfull then your owne, but rather harder; for the latter will prosper & come on, the other wil decay & fal into disease; as the pissing of blood and such like"5. He notes that the amount of milk production of a cow is generally more after they have calved and the temperament is important mainly because it makes them easier for the maid to milk.

Author Hannah Woolley wrote about the role of women in the English household in the late 17th century. She made several comments on how 'gentlewoman' who maintained dairies should look after them. (Here again we see the importance of women in the dairying field in the seventeenth centuries.) A dairy must be "kept clean and neat"6. She goes into detail about the management of a dairy by 'Country Gentlewoman' although the majority of her comments follow the advice given by Markham over half a century earlier. She does suggest that when "a Cow gives a gallon at a time constantly, the may pass for a very good Milch-Cow; there are some Cows which give a gallon and half, but very few who give two at a time."7 Markham actually suggests that receiving an excess milk from a cow "is a fault rather then a vertue, and proceedeth more from a laxativenesse or loosenesse of milke, then from any abundance... and therefore they are not truly called deepe [full] of milke."8

In 1717, writer Aaron Hill published an essay on dairy farming found in a letter ostensibly sent to him by a member of "a Society of Gentlemen", although he was likely the actual author. In it, he talks about "a new, and much more profitable Management of a

Dairy, than is commonly known, or practis'd"9. He begins by advising the manner in which the land that the

Photo: Hans Hillewaert

Sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia)

dairy will be located on should be prepared, talking at length about the use of 'St. Foyn' grass [sainfoin or Onobrychis viciifolia]. "Nothing is so sweet, nothing so innocent, nothing so nourishing, as the St. Foyn; but above all it is observ'd in encrease Milk in Quantity, and Quality, beyond any Grass yet known in the whole World; And it is for thuis Reason that I advise you to keep Cows upon it"10. Once the sainfoin crop had taken root (he recommended giving it five years), the dairyman was to buy 'about four Hundred Milch Cows' from Wales which were to be fed on sainfoin for twelve months or more to produce milk and then sold at a profit. This was to be used to purchase four hundred new milk cows. In this way, "I always preserve my Cows in their full Milk, and find it no uncommon Thing for one of these Welch Cows to be milk'd twice a Day, and afford a Gallon and a Half at a Meal....you will find, that coming from a poor Pasture to a rich, they will prosper, and encrease both in Milk and Size."11

Hill goes on to recommend building eight cow sheds, each housing fifty cows each of which is fed with new mown sainfoin. A man was to be appointed to oversee each shed and to mow the hay. Quarters were to be built to house him and five milkmaids.Hill also gives details of an interesting plumbing system designed to direct the milk into vats where it could be churned (by trained dogs!) to create butter and buttermilk. The maids could then use this raw material to make cheese. Whether such a thing was actually built or not, the design shows how the English mind had turned from small, 'Gentlewoman'-run, country estate-based dairies to something on an large, industrial scale with a focus on efficiency and profitability in less than forty years.12

Hill's essay

also gives us a connection between the three foods found in the period sailor's accounts which are a part of the dairy animal products: milk, butter and cheese. Markham notes that the "profit arising from milke... are three of especiall account, as Butter, Cheese, and Milke, to be eaten either simple or compounded"13. Woolley agrees, adding cream to the list of profitable milk products.14

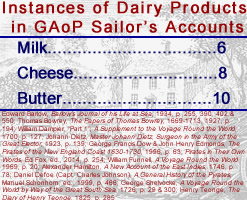

Dairy Product Instances Found in Golden Age

of Piracy Sailor's Accounts

Hack writer John Shirley noted that a dairy maid's responsibilites included seeing "that Butter and Cheese are made of proper Milks, and in their proper Season."15 He doesn't, however, specify what that season might be, although it is likely in the spring when the milk was felt to be the best.

The frequency with which the three dairy products are mentioned in sailor's accounts is found in the table at left. Butter and cheese are the most often mentioned dairy foods, which should not be surprising given that they were part of the navy diet. Most European sailors had a diet fairly similar to that of the English navy while at sea. The navy had selected a fairly well-balanced variety of foods which could both provide the calories necessary for a working sailor and hold up reasonably well during long voyages. Naturally, milk is the least mentioned dairy product (although not by much) and the instances of it being found and/or consumed by sailors are all land-based, almost certainly because of its short shelf life. Let's look at the three dairy products in greater detail.

Dairy Products Found in Sailors' Accounts During the Golden Age of Piracy |

||

|---|---|---|

| Butter | Cheese | Milk |

1 Joan Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England, 2006, p. 38-9; 2 Thirsk, p. 132; 3,4 Gervase Markam, The English House-wife, 1631, p. 190; 5 Markam, p. 191; 6 Hannah Woolley, The Gentlewomans Companion, 1675, p. 111 & 194-5; 7 Woolley, p. 200; 8 Markam, p. 192; 9 Markam, p. 194, 9 Aaron Hill, Essays for the Month of January 1717, 1717, p. 35; 10 Hill, p. 36-7; 11 Hill, p. 38; 12 See Hill, p. 38-44; 13 Markam, p. 195; 14 Woolley, p. 201; 15 John Shirley, The Accomplished Ladies Rich Closet of Rarities, 1696, p. 143;

Dairy and the Navy

Two of the three dairy products found in the sailor's accounts during the period were a standard part of the navy diet: butter and cheese. Because the navy'ssourcing and handling of these two items was similar, the navy's use of them are discussed together. Let's begin with a bit of navy's history with these two foods from before the golden age of piracy.

Artist: Nicolas Ozanne

Preparing Cargo, The Port of Bordeaux, Seen

from the

Wheat Dock (1776)

Historian David Loades identifies butter as part of the naval diet as early as the first half of the 14th century.1 General Surveyor of Marine Victuals Edward Baeshe was required to provide "half a quarter of a pound of butter" (or an eighth of a pound) on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays every week in 1565.2 This continued through the golden age of piracy (although the description was modified in the 17th century from 'half a quarter of a pound' to 'two ounces').3 The 1677 Victualling Contract permitted the substitution of "a wine pint of sweet olive oil" for butter and cheese4 when a ship was traveling south of the 39th North parallel because it was easier (and cheaper) to obtain olive oil in the Mediterranean.

Writing of the food he saw served to the English Navy in 1729, French author César de Saussure said that each mess of four sailors received "half a pound of butter for breakfast, and the same for supper"5. The butter would have likely been put in the oatmeal at breakfast and the peas at dinner. In defending the master's treatment of the men who mutinied and turned pirate on the merchant ship Adventure, surgeon Samuel Nixon mentioned that they "had Burgoo [oatmeal] for Breakfast, with Butter and Sugar" three days a week.6 Still, it is interesting that de Saussure specifies that butter is served at both meals, resulting in a total of 4 ounces of butter per man per day where the naval menu only calls for two.

The use of cheese in the naval service was even more ancient than butter. As early as 1253, King Henry III ordered the Sheriff of 'Hants' [Hampshire] to procure "20 weys [about 175 pounds] of hard cheese" for a voyage to France.7 As with butter, the 1565 contract spelled out the quantity each man was to receive: a quarter pound of cheese was provided on Wednesdays, Fridays and Saturdays8. Curiously, a victualling contract from February of 1637 specifies that cheese was to be issued at each meal on those days except for Friday dinner9. This is verified in Monson.10 By 1677, the Victualling Contract was more specific, stating that each sailor is to have "four ounces of Suffolk cheese, or two-thirds of that weight of Cheshire"11 without mentioning that the cheese provded for Friday dinner was any different than Wednesday and Saturday. This was reaffirmed in a letter from the Admiralty to the Navy Board in January of 1701 and by De Saussure, who travelled aboard the HMS Torrington in 1729.12

Historian John Ehrman notes that the navy obtained "butter from Suffolk and the other eastern countries" in England in the late 17th century.8 Paula Watson explains that in the early 18th century, butter was sold to the Victualling Board "under contract with one man [contractor] lasting for a year. The contract was usually placed in September."9 She says that in 1703 the lowest price bidder, Richard Maundrell, was awarded the contract at 3-1/2 pennies per pound of butter, a contract which he retained until 1709.

Unlike most other foods, neither butter nor cheese were sent to the navy stores, but were delivered directly to the ship. The 1731 Regulations and Instructions related to his Majesty's Service at Sea specified that "His Majesty's Ships for Foreign Voyages, ... shall be supplied three Months Butter and Cheese, the Remainder of those Species being to be made up in Olive-Oyl; but for the Mediterranean"10. Although order was issued six years after the end of the golden age of piracy, historian N.A.M. Rodger points out that it was "largely a codification of orders issued at various dates in the past as far back as 1663"11.

Aship traveling in locations that were hot during the day and cool at night would not have been an optimal place to store dairy products. Even the butter stored in navy facilities in England suffered decay. Sir Thomas Allen, admiral of the English White Fleet reported on February 18, 1667 that while being victualled in the Downs that the HMS Monmouth returned "8 of 9 firkins of butter, it stank so."20 Historian N. A. M. Rodger cites a mid-eighteenth century naval document which explains that the butter "next to the firkin [cask sides was] not fit to be issued"21.

1 Elizbethan Naval Administration, CS Knighton and David Loads, eds, 2013, p. 594 & David Loades, The Tudor Navy, An Administrative, political and military history, 1992, p. 84; 2 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 140; 3 See for example, William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 56 & J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 166; 4 Tanner,A Descriptive Catalogue..., p. 167; 5 César De Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 364; 6 Samuel Nixon, “49. Mutiny on the Ship Adventure”, Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 254; 7 Calendar of Liberate Rolls, 1251-1260, Vol. 4, 1959 p. 140; 8 Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, p. 140; 9 CSP Domestic, 1636-7, 1867, p. 452-3; 10 William Monson, The Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson, Vol. IV, M. Oppenheim, ed., 1913, p. 56; 11 J.R. Tanner, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, 1903, p. 165-6; 12 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 255 & César De Saussure, A Foreign View of England In The Reigns Of George I and George II, Madame Van Muyden, ed., 1902, p. 364;

8 John Ehrman, 1957, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction, p. 145-6; 9 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714", University of London PhD thesis, 1965, not paginated; 10 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 63; 11 N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, 2004, p. 320;

20 R. C. Anderson, The Journals of Sir Thomas Allin, 1660-1678, Volume II, 1660-1678, Vol. 80, 1940, p. 7; 21 N. A. M. Rodger, The Wooden World, 1986,p. 92;

Butter

Called by Sailors: Butter

Appearance: 10 Times, in 10 Unique Ship Journeys from 9 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: Kinsale, Ireland; London, England; Bergen, Norway; Mauritius; Bandah Aceh, Indonesia; Nicobar Islands; St Catherine's Island, Brazil;Juan Fernandez, Chile; Cape Cod, Massachusetts, US;

Since salted butter was a standard part of the English naval sailor's diet, it was often found in the diets of other types of sailors. Yet, this staple is not found in any of the naval accounts from the period. This may be because it was so familiar to English navy sailor, it wasn't discussed in detail by them.

There are actually quite a few interesting details concerning butter found in the sailor's accounts from the period. Lifetime sailor Edward Barlow mentions it on three different voyages, all of them on merchant ships. He explains that the cattle in Norway "have milk and butter pretty plentiful" during the summer in 1675.12 At a stop on the island of Mauritius in 1689, he explained that the cows there "give very excellent good milk, and they make very good butter for present spending [use], but it will not keep very long, by reason of the heat of the weather."13 He also marvelled at the cost of food in Kinsale, Ireland in 1702 where "good provisions were very cheap ...buying good salt butter for three halfpence per pound, and fresh butter for twopence"14.

Artist: Jean-Francois Millet

Young Woman Churning Butter (c. 1848-51)

Barlow's differentiation between 'salt butter' and 'fresh butter' provides the opportunity to discuss the process of making butter and the resulting output. Gervase Markham recommended that dairy woman make butter from cream. (Before the butter making process was commercialized in the early eighteenth century, the farm women dealt with the dairy, selling excess dairy products in local markets. See the previous section for more on this.) Markham recommended, "take your Cream, and through a strong and clean cloth strain it into the Churn". The butter was then to be churned "in the coolest place in your Dairy, and exceeding early in the morning, or very late in the evening" in the summer and "in the warmest place of your Dairy, and in the most temperate hours as about noon, or a little before or after" in the winter. It was to be churned rapidly, listening for the sound of churning to change from "solid, heavy and entire" to "light, sharp, and more spiritly". It was then to be checked to see that it was yellow, recovered and churned "with easie stroaks round and not to the bottom". He warned not to let it get too hot or cold, "for if it be over-heated, it will look white, crumble, and be bitter in taste; and if it be over-cold it will not come at all, but will make you waste much labour in vain". The result was then to be gathered, put into a wooden or ceramic bowl "and if you intend the butter sweet and fresh, you shall have your bowl or panshion [pancheon - a shallow dish] filled with very clean water, and therein with your hand... work the butter, turning and tossing it to and fro, till you have... wash'd out all the butter-milk... without any moisture" in it. It is then sliced and further dried and then salted with "so much salt as you think convenient, which must by no means be much for sweet butter"15. This is likely what Barlow means by 'fresh butter'.

In his magnificently detailed accounts of the 167 ton merchant vessel Mary Galley, merchant Thomas Bowry lists 30 ferkins of butter for a voyage planned for India in September of 1704.16 A firkin is a wooden cask which held about 9 gallons (about 56 pounds of butter) in the eighteenth century.17 Butter was typically made during the summer and early fall and packed into these small casks. "In packing these firkins, it was common practice to bore a small hole in the head, just before shipping, and pour in as much clear, well skimmed brine as was required to fill any vacancies between the butter and the package, thus displacing the air, and closing the hole with a well fitting peg cut off flush with the surface."18 It was then stored in a cool, dry place allowing better preservation against spoilage.

A Butter Firkin (19h Century)

Historian Joan Thirsk notes that the "Dutch were more expert than the English at keeping butter fresh" in the mid-seventeenth century, importing their best butter to sell to those in the know in England and suggesting that it may have been they who taught the English how to preserve butter well.19 As seen in the previous section, there were still problems keeping the butter fresh.

Still, butter was an important staple to sailors. No where is this made more plain that in a secondhand account of a coal vessel sailing from Newcastle which was written by slave ship master Thomas Phillips in 1693. He explains that the

collier master...having lock'd up the firkin of butter from [the crew], contrary to custom, and plying to windward with the tide among the sands, standing on one tack as near a sand as he thought proper, order'd the helm a-lee [on the sheltered side], to go about; when the ship was well stay'd [pointing into the wind], he call'd to hale [haul] the main-sail, but his men answer'd unanimously, that not one of them would touch a rope till the firkin of butter was brought to the mast. He began to expostulate with them, but to no purpose, and seeing the ship drive near the sand with all sails aback, he promis'd them they should have it assfoon as the sails were trimm'd, and the ship had gather'd way; the men reply'd, that seeing was believing; whereupon, finding there was no other remedy, he run down to his cabin to fetch the butter, and laid it at the mast; then the men went to work, but too late, for e'er the sails could be hal'd about and fill'd, the ship struck upon the sand, and never came off again; so that as the sea proverb is, he lost a Hog for a halfpenny-worth of Tar.20

Some information is provided about the quantity of butter brought or bought on voyages. When the privateer ship Speedwell reached Brazil on their way to the western side of the Americas with about 100 men aboard, captain George Shelvocke puchased 300 pounds of butter (about 5 firkins) from a French vessel, the Wise Solomon.22 If he followed the naval practice of giving each man 1/8 of a pound of butter three times a week, it would have lasted about 8 weeks. It was previously noted that the merchant Mary Galley took 30 firkins of butter aboard to sail for India in 1704. The ship had 26 to 30 men aboard for the three year voyage.23 If the men received 6 ounces a week, this would have lasted them about a year and month, easily seeing them to India (and then some)

Artist: Jean-Francois Millet

Ambrose Cowley and his men taking in provisions on Juan Fernandez,

From

An Historical Account of All the Voyages Round the World Performed by English

Navigators, Volume I (1774)

under normal circumstances, provided the butter lasted that long. Such quantities paled in comparison to the amounts provided to the English navy. Historian Paula K. Watson reports that the navy supplied 3342-1/2 pounds of butter aboard Sir Cloudesley Shovell's Mediterranean Squadron of eighteen ships in 1703.24

When we think of butter, we think of that made with cow's milk or cream. Ships on long-distance trips to remote locations didn't usually have this luxury. First Mate William Funnell of the privateer vessel St. George gives a second-hand account of what some French pirates did when they had to do for dairy while hiding from the Spaniards off the coast of Chile some time in the late 17th or early 18th century. The French decided "to come to this Island of Juan Fernando’s [Frenandez], they being twenty in number, and there to lie nine or ten Months; which accordingly they did, and landed on the West side of the Island; then drew there little Armadilla ashoar, and in a small time brought the Goats to be so tame, as that they would many of them come to themselves to be milked; of which Milk they made good Butter and Cheese, not only just to supply their Wants whilst they were upon the Island, but also to serve them long after"25.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, p. 255, 402 & 550;Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, 194-5;William Dampier, "Part 1", A Supplement to the Voyage Round the World, 1700, p. 146; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 63; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 254; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 20-1; Daniel Defoe (Capt. Charles Johnson), A General History of the Pyrates, Manuel Schonhorn, ed., 1999, p. 466; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 29; 12 Barlow, p. 255; 13 Barlow, p. 402;14 Barlow, p. 550; 15 Gervase Markham, A Way to Get Wealth, 1668, pp. 145-7; 16 Bowrey, p. 194; 17 Edward Phillips, 'Firkin', The New World of Words, 6th ed., 1706, not paginated & Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelsons Navy, 2014, p. 175; 18 "The development of bulk packages", Butter Through the Ages, webexhibits.org, gathered 1/4/24; 19 Joan Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England, 2006, p. 123; 20 Thomas Phillips, "A Journal of a Voyage Made in the Hannibal", A Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol VI, Awnsham Churchill ed, 1732, p. 175; 22 Shelvocke, p. 29; 23 Bowrey, pp. 114 & 194; 24 Watson, not paginated; 251 Funnell, p. 20-1;

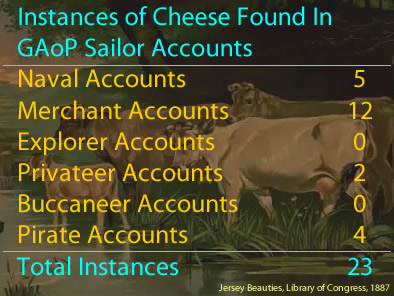

Cheese

Called by Sailors: Barley, Barly

Appearance: 8 Times, in 8 Unique Ship Journeys from 8 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Iceland; Basrah, Iraq; St Catherine's Island, Brazil; Juan Fernandez, Chile; Cape Cod, Massachusetts;

Like butter, cheese was a standard part of the English naval sailor's diet and thus was usually a part of the diets of non-naval sailors.

One may well wonder why a lesser amount of Cheshire cheese was

equivalent to a greater amount of Suffolk cheese. The 1731 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea, codified the idea that "Two Thirds of a Pound of Cheshire Cheese, is equal to one Pound of Suffolk"8. This had everything to do with the quality of the two types of cheese. Cheshire cheese was made with whole milk, while Suffolk was made with skim during the latter seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It was believed that the dairy maids in Cheshire were better at making cheese and the pastures the milk cows ate from were better.9 Cheshire also was efficient at pressing the whey out of the type of large cheeses the navy bought, probably because they appear to have been the first area to use large cheese presses for the process.10

Suffolk cheese "had the reputation of being dry and so hard that it was difficult to cut, let alone eat and digest" while "as far as we can tell, Cheshire cheese at this time had a flaky consistency and a mild but full flavour."11 Several modern authors gleefully list the faults of Suffolk cheese as noted by period sources. "Suffolk cheese developed a poor reputation being impossible to get into other than with a hammer and chisel. It was thus known as 'Bang and Thump'. In his diary of 4 October 1661 Samuel Pepys wrote: "and so home, where I found my wife vexed at her people for grumbling to eat Suffolk cheese, which I also am vexed at.. "12 The same year, sailor Edward Barlow aboard the Navy ship Augustine complained that the ship's purser gave them their cheese allowance "without scraping, the foul and the clean together, and the rotten with the sound, and mouldy and stinking and all together, and we had Hobson's choice, that or none"13.

A variety of modern commenters note

a staple on sea voyages because it remained relatively good during long journeys.

Seventeenth century commenters talk about the proper time for milking, with Woolley again following Markham's text. "The best and most commended howers [hours] for milking, are Indeed but two in the day, that in the spring and summer time which is the best season for the dairy, is betwixt five and sixe in the morning, and sixe and seven a clocke in the evening"9.

1 Edward Barlow, Barlow's Journal of his Life at Sea in King's Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, 1934, p. 390; Thomas Bowrey, The Papers of Thomas Bowrey, 1669-1713, 1927, p. 195; Johann Dietz, Master Johann Dietz, Surgeon in the Army of the Great Elector and Barber to the Royal Court, 1923, p. 139; George Francis Dow and John Henry Edmonds, The Pirates of the New England Coast 1630-1730, 1996, p. 59; Pirates in Their Own Words, Ed Fox, ed., 2014, p. 254; William Funnell, A Voyage Round the World, 1969, p. 21; Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, 1746, p. 78; George Shelvocke, A Voyage Round the World by Way of the Great South Sea, 1726, p. 29; 8 Regulations and instructions relating to His Majesty's service at sea,1st ed, 1731, p. 61; 9 Peter J Atkins, “Navy victuallers and the rise of Cheshire Cheese”, International Journal of Maritime History, Vol. 34 Issue 1, Feb. 2022, p. 200; 10 Atkins, p. 202; 11 Atkins, p. 199 & 201;

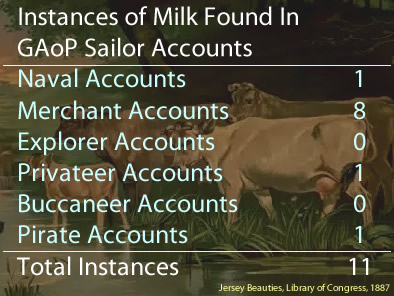

Milk

Called by Sailors: Barley, Barly

Appearance: 7 Times, in 5 Unique Ship Journeys from 5 Sailor Accounts.1

Locations Found in Sailor's Accounts: London, England; Tunis, Tunisia; Oman, Africa; Mocha, Yemen; Chileo Island & Coquimbo, Chile;

Barley was familiar to English sailor, meaning it is never described or discussed in detail by them, typically just being listed among other grains found in the places they visited. John Covel does mention finding bread for sale in Tunis Castle at Tunisia which was made with 'barley flour'. Thomas Bowrey lists 30 bushels of "oats, barley and bran" among the victualling stores put aboard his merchant vessel Mary Galley in 1704, indicating that it was used as food during the ensuing journey, but provides no further detail.2 It almost sounds as if this were feed for animals brought aboard, although none are listed in this document.

Seventeenth century commenters talk about the proper time for milking, with Woolley again following Markham's text. "The best and most commended howers [hours] for milking, are Indeed but two in the day, that in the spring and summer time which is the best season for the dairy, is betwixt five and sixe in the morning, and sixe and seven a clocke in the evening"9.

9 Gervase Markam, The English House-wife, 1631, p. 194