History of Pirate Surgeons Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

The History of Sea and Pirate Surgeons, Page 4

Sea-Surgeons and Buccaneers

Artist: Charles Brooking

The Capture of a French Ship by RF Privateers (Early 18th c.)

Buccaneers are often rather unfairly lumped in with the pirates, perhaps because they were private ships mounted to harass the Spanish by taking their ships and cargo. They were actually privateers, not pirates, because they had official Letters of the Marque from England giving them permission to capture ships of enemies of England. Without the Letters of the Marque, this would have been considered piracy. With them, it was a sanctioned part of warfare – at least as far as England was concerned. The Spanish may have had a different view.

Being engaged in legal voyages, buccaneers were able to attract surgeons into their service. Robert Byndloss, George Holmes, Richard Browne and Alexandre Esquemeling are some of the English surgeons who joined the buccaneers on their voyages. G.M. Longfield-Jones notes that "the profession could bring substantial financial rewards"1 based in part on Robert Byndloss's career after retirement from buccaneering. Byndloss became a wealthy landowner and part of the Jamaica Assembly, although his temperament was such they that they eventually threw him back out of the assembly. He and buccaneer Henry Morgan both lived in Jamaica and were friends. In fact, Byndloss married Morgan's sister Anne Petronella in 1665.

Artist: Iivan Aivazovsky - Excerpted from The Ninth Wave (1850)

Richard Browne arrived in Port Royal in 1668 as a medical officer on the naval frigate Oxford. He sailed to join the Panama Fleet in the Oxford. Browne was one of the few people to survive the explosion of the Oxford's magazine. Ernest Cruikshank explains,

While the officers then assembled were dining together on the quarter-deck of the Oxford, which had been chosen by Morgan as his flagship, her magazine exploded from some unknown cause, and besides several of the guests, nearly the whole of her crew of two hundred men were killed, drowned, or horribly wounded. Surgeon Browne, after being hurled through the air into the sea, saved his life by getting astride of a floating fragment of her mizen-mast. He reported that only six men and four boys belonging to her crew were rescued.2

Such accidents were just cause to have a surgeon at the ready. Then sailors knew that buccaneering voyages were dangerous and so

.jpg)

Artist: Howard Pyle - So the Treasure Was Divided, (1905)

preferred ships containing surgeons. The buccaneering captains were so eager to show concern for the health of their sailors that they built provisions into their articles establishing rates of pay for wounds received in the line of duty.

In his account of preparing for a buccaneering voyage, Alexandre Exquemelin details "what rate each one ought to have that is either wounded or maimed in his body, suffering the loss of any limb; as, for the loss of a right arm, six hundred pieces of eight, or six Slaves; for the left arm, five hundred pieces of eight, or five slaves; for the right leg, five hundred pieces of eight, or five slaves; for the left leg, four hundred pieces of eight, or four slaves; for an eye, one hundred pieces of eight, or one slave; for a finger, the same as for an eye; all which sums are taken out of the common stock of what is gotten by their piracy."3

1 G.M. Longfield-Jones, "Buccaneering Doctors", Medical History 36:2 (1992:Apr.) p. 188; 2 Brigadeer-General Ernest Alexander Cruikshank, The Life of Sir Henry Morgan, p. 98-9; 3 Alexandre Exquemelin, The History of the Buccaneers of America, p. 51-2

Buccaneer Surgeon Alexandre Exquemelin

Exquemelin is an interesting buccaneer surgeon in his own right. He penned the book The Buccaneers of America, which makes him one of several pirate/buccaneer surgeon writers. He joined the Dutch East India company in 1657 where he served as a cabin-boy until the ship he was on wrecked on the west coast of Australia. Making their way back to Java, he apprenticed to a barber-surgeon and returned to Holland in 1665.1

Dutch Title Page to Exquemelin's

The Buccaneers of America (1678 Edition)

Like many surgeons, Exquemelin learned his trade via apprenticeship. A 'normal' apprenticeship lasted seven years, during which the apprentice was taught the details of surgery by his master. A surgeon's apprentice began by performing menial tasks such as preparing medicines and bandages, readying the tools for surgery and changing dressings. As he progressed, the assistant would be allowed to assist with the surgical operations. However, because the need for sea-surgeons was so great, many became surgeons in their own right without fully completing an apprenticeship. Elizabeth Bennion tells us that land-based "apprentices often ran away to sea and pose as surgeons to the authorities whose only concern was to assure the crew there was a surgeon on board."2

Within a year of his apprenticing, Exquemelin joined the French West India Company which unfortunately dissolved shortly after his arrival at Tortuga. As a result, he was forced into indentured servitude to a French buccaneer. Exquemelin said he found himself in "the hands of the most cruel and perfidious man that ever was born, who was then governor, or rather lieutenant-general, of that island. This man treated me with all the hard usage imaginable, yea, with that of hunger, with which I thought I should have perished inevitably."3 Exquemelin became very ill "through the manifold miseries I endured, as also affliction of mind"4 which caused his master "to fear lest he should lose his moneys with my life."5

Exquemelin was redeemed from servitude by a physician, who healed him, trained him for a year in the medical arts, and only asked him to repay his ransom of seventy pieces of eight. Exquemelin then struck out on his own with only a few of his seven years of 'required' surgical apprenticeship finished. He explains it rather poetically, as only a writer would. "Being now at liberty, though like unto Adam when he was first created by the hands of his Maker- that is, naked and destitute of all human necessaries, nor knowing how to get my living – I determined to enter into the wicked order of the Pirates, or Robbers at Sea. Into this Society I was received with common consent both of the superior and vulgar sort, and among them I continued until the year 1672. Having assisted them in all their designs and attempts, and served them in many notable exploits of which hereafter I shall give the reader a true account, I returned to my own native country."6

Exquemelin's "true account" is divertingly long on travel detail and adventure and disappointingly short on medical observations. This may have been because of his limited training, although it was more likely due to the style of travel books most appreciated by the public at this time.

1 Longfield-Jones, p. 191; 2 Elizabeth Bennion, Antique Medical Instruments p. 155; 3 Exquemelin, p. 25; 4 Ibid; 5 Ibid; 6 Ibid, p. 26

Other Buccaneers

Accounts of a second group of buccaneers provides us with some interesting first hand accounts of buccaneer surgeons. These accounts concern a loose confederation of privateer captains including John Coxon, Richard Sawkins, Bartholomew Sharp, Edward Cooke, Peter Harris, Robert Alleston and William Macket. Curiously, the names of the authors of these buccannering accounts are probably more recognizable to most readers than the actual captains: Basil Ringrose, William Dampier and Lionel Wafer.

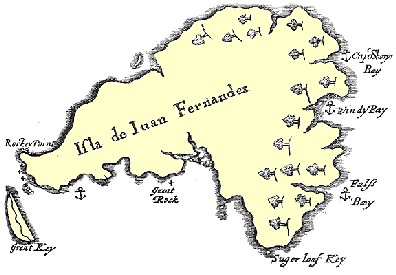

Basil Ringrose's Map of Juan Fernandez Island (1685)

Ringrose's writings are usually included with Exquemelin's book, which may be why his name is the least recognizable of the three authors. He seems to have been something of a Renaissance man, dabbling in many different trades useful to the buccaneers including navigation, map-making, language interpretation and documenting.

In his entry on Basil Ringrose, Philip Gosse says that, "Ringrose kept a very full and graphic journal, in which he recorded not only [the buccaneers'] exploits, but also their hardships and quarrels, and gave descriptions as well of the various natives and their customs, and drew charts and sketches."1 He is sometimes identified as a surgeon, although it is difficult to verify this and his writings do not give any indication that he knew more about medicine than any other educated seaman.

Dampier is probably the best known of the three writers, although he definitely wasn't a surgeon, nor was he ever identified as one.

William Dampier(1698)

Dampier does highlight the importance of the surgeon to a buccaneering crew several times in his book. One incident he mentions concerns a mutiny staged by the crew in 1687 while their ship was at Mindanao. The mutineers had "bound themselves by Oath to turn Captain Swan out, and to conceal this Design from those that were ashore, until the Ship was under Sail; which would have been presently, if the surgeon and his Mate had been aboard; but they were both ashore, and they thought it no Prudence to go to Sea, without a Surgeon"2. To get the surgeon aboard, the mutineers sent word that one of the men on the ship had "broke his leg by falling in the Hold."3 The ship's surgeon didn't want to leave Mindanao, so he sent his surgeon's mate Herman Coppinger. Dampier tells us that "I went aboard with him, neither of us distrusted what was designing by those aboard, till we came thither. then we found it was only a Trick to get the Surgeon off [the land and onto the ship]".4

Another incident Dampier comments upon occurred when sea-surgeon Lionel Wafer was wounded during a trip across the Isthmus of Darien [modern Panama]. Wafer burned his knee during the crossing due to carelessness of a man drying powder and had trouble keeping up with the crew as they hiked across the Isthmus. Dampier explained that "all of us [were] the more concern'd at the Accident, because liable our selves every Moment to Misfortune, and [there was] none to look after us but him.5 Dampier clearly had a high regard for the presence of a surgeon on a ship.

1 Philip Gosse, The Pirate’s Who’s Who, p. 259; 2 William Dampier, Memoirs of a Buccaneer, Dampier’s New Voyage Round the World, p. 253; 3 Ibid; 4 Ibid, p. 254; 5 Ibid, p. 20