Health 'Insurance' at Sea: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Next>>

Health 'Insurance' at Sea During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 2

Sea Surgeon Provision - Duties

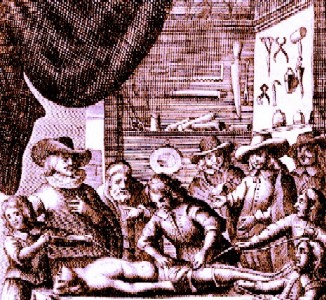

Johannes Scultetus, l'Arcenal de Chirurgery, frontispiece (1672)

As the surgeon became an integral part of ship-board life, the duties he was expected to perform in that capacity solidified. Much of a surgeon's duty seems obvious; Nathaniel Boteler remarked in his Dialogues [a book about the practices of British Navy written around 1630-16401] that he didn't explain the duties of the surgeon "partly in that their functions are and charges are everywhere known, and partly because that these are not officers peculiar to the sea, as all the rest forementioned are."2 However Boteler elsewhere at least hints at the surgeon's duties, explaining that when the ship was preparing for battle, the surgeons were to be "in the hold also, with their chests and instruments to receive and dress all the hurt men"3.

The book of "lawes" published in 1621 by the East India Company provides a few more detailed instructions as to the duties of the ship's surgeons, although even they are fairly obvious. The individual ship's surgeons were to

give their best advice and counsell, that all needfull Medicines and other things, may be provided, whereof they shall take a carefull view, when the [surgeon's] Chest [of medicine and instruments] shall be delivered to their charge, that nothing be wanting, which conveniently may be had for the preservation of mens lives, and curing of their diseases. ...They shall use their best endevour and skill (through the whole course of their Voyage) in those thinges which concerne their places4

As befits any company's policy, the surgeons were also to bring their surgeon's chests back to the 'Chirurgion Generall' with everything not used remaining "in them, unto the said for the use of this Company."5

John Woodall

Although the company charged the surgeons with checking their medicine chests, the chests were actually stocked by the 'Chirurgion Generall' in the person of John Woodall. Woodall originally wrote his book the surgions mate to be included in the East India ships after finding himself "wearied with writing for every shippe the same instructions anew"6. The goal of his book was "to instruct such young men as were imployed in the East Indies"7. While the East India company's 'lawes' didn't provide much detail about the duties of ship's surgeon and his mates, Woodall did.

He includes a specific section in his book titled "The Office and Duty of the Surgions Mate." Here he advises the mates "ought ...to be gentle, and kinde in speech, and actions towards all: pittifull to them that are diseased, and diligent in ministring to them such fitting remedies as he shall receive". In fact, he tells the surgeon's mate to watch "the whole passages of the diseased people, considering both when they began to bee sicke... the causes thereof, what hath beene applied either inwardly or outwardly, what operation the medicine had... and to keepe a Jornall in writing of the daily passages of the voiage in that kind".8

Woodall advised practicing shaving as well as bloodletting because "it is a credit of a young Artist to take a vaine smoothly and neate". The surgeon's mates were to make sure the steel instruments were kept "cleane from rusting, and to set [sharpen] his Lancets and Rasors as often as neede is". Woodall recommended the surgeon's mate "read much, I meane in Chirurgery and Phisicke [physic - medicines], and well to consider and beare in minde what he reades, that as hath neede of the helpe of his bookes hee may againe finde the thing he once read". (We would all do well to heed that advice.) Woodall also said the mate was to "daily visite the Cabines of men, to see who hath and sickesse or Imperfection" and be ready to treat such men when he found them. 9

This practise of inviting the sick and wounded to meet with the ship's surgeon or his surgeon's mates daily has support from a variety

Bandaging a Wounded Arm, One of the Daily Duties,

Johannes Sscultetus, l'Arcenal de Chirurgery (1672)

of sources. Stephen Bown explains that it was the duty of the surgeon's mates to muster the ship's sick each morning"10 and in "the evening the surgeon's mate made a round of the ship inspecting the invalids in their quarters if they were officers or warrant officers and in the sick bay if they were common sailors."11

Former sea-surgeon Tobias Smollett's wrote what appears to be a semi-autobiographical fictional book about a surgeon's assistant named Roderick Random. In it, Random observed the ship's surgeon visiting "the sick, and having ordered what was proper for each, I assisted Thomson [another surgeon's assistant on the ship] in making up his prescriptions"12.

Random's duties included another, similar task. "At a certain hour in the morning, the boy of the mess went round all the decks, ringing a small hand-bell, and, in rhymes composed for the occasion, invited all those who had sores to repair before the mast, where one of the doctor's mates attended, with applications to dress them."13 Smollett's is the only account I've found that mentions the 'boy of the mess' performing this duty. The boy of the mess is a young man who waited on the officers when they were dining. This term does not appear to have had wide usage, however.14 Since this role would only occupy some of his time, he would presumably be called upon to perform other duties as needed.

Sea surgeon John Moyle likewise explains that the surgeon's mate's plaster or dressing box and "your pocket Instruments must be carried every Morning to the Mast between Decks, where our Mortar [presumably a brass mortar] is usually rung, that such as have any Sore or Ailment may hear in any part of the Ship, and come thither to be drest."15

Perhaps the most extensive list of requirements for an English ship's surgeon came from the 'Sea-Laws of France' dating to 1681. These were translated and published by Alexander Justice in 1705 and re-appeared, almost verbatim, two years later in The Sea-Mans Vade Mecum.

Artist: John Nicholls

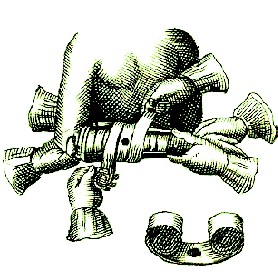

A Medicine Chest, From The Quack

Doctor Outwitted, British Museum (1710)

- In every Ship, even in the Fishing-Ships, making long Voyages, there shall be one or two Surgeons, according to the Circumstances of the Voyages and Number of the Persons.

- None shall be receiv'd as Surgeons on board of Ships, till they have been examined and found capable by two Master Surgeons, who shall give their Certificates.

- The Owners shall be obliged to provide the Surgeon's Chest well stor'd with Drugs, Ointments, Medicaments, and other things necessary for treating Sick Persons during the Voyage; and the Surgeon shall provide the Instruments of his Profession.

- The Chest shall be visited by the most Ancient Master Surgeon of the Place, and by the most Ancient Apothecary, provided it be not the same that furnished the Drugs.

- The Surgeons shall be oblig'd to get their Chest visited, at least 3 Days before the Departure; and the Master Surgeon and Apothecary, to do it within four and twenty Hours after they are thereto requir'd, on Pain of thirty Livres Fine [although currency conversion from this period is quite imprecise, 1 pound sterling was worth about 14-24 French livres16], and the Damages of Demurage [a fee charged for failure to load or unload cargo].

- No Master shall receive any Person to serve on board his Ship as Surgeon, without producing a Copy of the Attestations of his Capacity, and of the Condition of his Chest in due Form, under Pain of fifty Livres Fine.

- We enjoin the Surgeon of Ship, in case they discover and contagious Distemper, to acquaint forthwith the Master, that he may take his Measures accordingly.

- They shall exact nor receive nothing of the Marriners sick or wounded in the Service of the Ship, under Pain of Restitution, and an Arbitrary Fine.

- The Surgeon not to leave the Vessel in which he is engaged, before the Voyage is accomplish'd, under Pain of the Loss of his Wages, or being fin'd in one hundred Livres, and of paying the like Sum for Damages to the Master.17

Whether these laws were actually used by English ships is not clear. England does seem to have been in the practice of borrowing laws and applying them to their sea travel. In his introduction to these laws Justice explains: "Tho' the French be Enemies to us, we should not be so much Enemies to our selves, as to reject the Use of good laws, meerly because they are in Force amongst them, or have been devis'd by them."18 However, given that this particular set were printed for the English several times, they were at least aware of them.

1 John Knox Laughton, "Boteler, Nathaniel", Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 5, gathered 1/31/16; 2 Nathaniel Boteler [Butler], Boteler's Dialogues, Edited by W.G. Perrin, 1929, p. 64; 3 Boteler, p. 293; 4,5 East India Company, The lawes or standing orders of the East India Company, 1621, p. 48; 6 John Woodall, "Letter to the Reader", the surgions mate, 1617, not paginated; 7 Woodall, "The Epistle Dedicatorie", the surgions mate, 1617, not paginated; 8,9 Woodall, "The Office and Duty of the Surgions Mate", the surgions mate, 1617, not paginated; 10 Stephen R. Bown, Scurvy: How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medieval Mystery of the Age of Sail, 2003, p. 90; 11 Bown, p. 91; 12 Tobias Smollett, The Adventures of Roderick Random, 1748, p. 170; 13 Smollett, p. 174; 14 Thanks to David Fictum for sharing this information on the boy of the mess during a discussion on the Authentic Pirate Living History Facebook group, gathered 2/20/16; 15 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon,1693, p. 45-6; 16 This is a nighmarish number to accurately find, but if you feel brave, see Pierre Martou's Publishing Currency Converter, "How much was 1 French livre worth in 1650 USD?" on Yahoo! Answers and "Conversions between Eighteenth Century Curriencies" at w3r-us.org, 17 Alexander Justice, A General Treatise of the Dominion of the Sea And a Compleat Body of the Sea-Laws, 1724, p. 293-4; 18 Justice, p. 249

Ship's Surgeon Provision – Training

"This I think. I may venture to say, That many of the Chirurgeons, hut more especially their Mates, which are employ'd in the Fleet, are not altogether so well Qualify'd as they ought to be; and yet the poor Men are forc'd to depend on their Skill, not only in Chirurgery, but Physick also, in the Absence of a Physician." (Josiah Burchett, "To the Reader", Memoirs of Transactions at Sea During the War with France, 1703, not paginated)

Surgeon Bleeding, His Young Assistant Catching It (1634) - Wellcome

While the duties of a surgeon were not strictly defined, much was made in the period literature about the suitability and training of the surgeons and surgeon's mate. Josiah Burchett was Secretary of the Admiralty for fifty years, encompassing almost the entire golden age of piracy, so he he must have had some broad understanding of the problems the British Royal Navy faced with regard to surgeons on ships.

The training of sea surgeons during this time would take place in one of two ways - through apprenticeship to a sea-surgeon or via land-based training.

The first was the traditional method of apprenticing a surgeon to a master for a period of seven years. In theory a surgeon-in-training was articled by his parents to the master's guild, possibly even earning a license to practice at the end of internship.1 Sea surgeon James Yonge took this route, being "bound for eight years to Mr. Silvester Richmond, Surgeon of the Constant Warwick... [a ship of] thirty-one guns, 150 men. She was a ship that sailed well and had good luck in taking prizes."2 While the entirety of Yonge's training took place in ships, he followed Woodall's advice 'to read much' for he was able to "acquire a comprehensive knowledge of English and European medical literature, [although] he never attended any formal lectures during his seven years as mate."3

Barber Surgeon's Hall on Monkwell Street, London (1800) - Wellcome

Similar to training at sea, training on on land was often a seven year apprenticeship performed "under the aegis of the Company of Barber-Surgeons of London or one of the provincial companies of barber-surgeons in which case, theoretically at least, they would have first have had to be examined and approved by the London Company."4

A candidate for member of the Barber-Surgeons Company was interviewed at the Company's Hall in London, where it was verified "that the applicant was not suffering from any deformity or chronic disease and that he could read and write" and knew a little Latin. If the members of the Company were satisfied, the candidate was indentured to a master, typically for seven years, sometimes longer. Most of these candidates were 12 or 13 years old.

When the apprenticeship was complete, he returned to Barber-Surgeon's Hall to be examined.

Barber-Surgeons Admitting a New Member at Monkwell Street

(1834) From the Wellcome Collection

"The successful candidate was granted the first preferment of grace, as it was called, with a limited license to practice [as a journeyman]. After gaining further experience, he could proceed to the higher degree of Master of Anatomy and Surgery, which was the second preferment of grace, by reading a thesis before the Company every six months or by offering himself for periodical re-examination."5

Some members of the Company became sea surgeons as a matter of practicality. Setting up a practice without experience could be difficult so surgeons joined merchant ships because they were "just out of school, with no funds or prior opportunities for practice. Most served for one or two trips and then quit."6

Other surgeons saw the sea surgeon practice as an opportunity. On long voyages, they would encounter illnesses and problems they would not have seen had they stayed practicing in England. This experience "would have considerably advanced their medical education and improved their surgical skills. They would have had to deal with a multitude of horrendous wounds, while at the same time coping with the diseases which could spread through a ship’s company leaving dozens of men incapacitated."7

Still other surgeons "were pressed into service in the provinces [where they had been apprenticed outside of the London Company] and were exempted from serving as a journeyman. They were admitted to the guild as foreign brothers without the privileges of full membership"8. The 'foreign brothers' category of membership in the Barber-Surgeons Company existed to allow those trained outside of the London Company to be licensed by the Company so that they could practice their trade in England. (English naval ships being included in this description.)

Artist: Jacques Callot

Counselling Patients at the Hospital, From L'hôpital of

Les misères et les malheurs de la guerre (1632)

Outside the apprenticeship programs, English hospitals began training students in the mid-17th century with St. Bartholomew's Hospital in Smithfield, London establishing a program to train private students in the hospital wards in 1662. Other hospitals followed suit. "In 1693 the Lord Mayor, Sir Robert Clayton, appealed for funds to rebuild St. Thomas’s, and by 1695 it too had established an independent teaching organization with all the advantages of ‘walking the wards.'"9

The Barber-Surgeons Company was naturally opposed to hospital training. They complained in 1695 that such training was 'breeding soe many Illiterate and unskillful pretenders to Chyrurgery [such as those] att St. Thomas's hospital or wherever else the like ill Practises are used'. "The Barber-Surgeons had good reason to protest, for the hospitals were offering to give students a complete training in six to twelve months. In return for this saving of some six years of apprenticeship the staff charged high fees and turned out unskilled men 'to practise for themselves either about the town, in the army or navy or elsewhere with the reputation of being bred in an Hospital'."10

The British Navy had different concerns regarding surgeons. As we have seen, they were required to have surgeons on board every ship beginning in 1635. During times of war this was a particular challenge as the fleet size rapidly expanded in preparation for upcoming battles. As a result, "the practice of naval medicine on board ship took place within the limits of operational necessity."11 Point of fact, "the Council decided on February 2, 1665, to facilitate medical entry into the navy; quantity, not quality, must direct the policy of courts of examiners. Admittedly, the order, worded with great care, implied safeguards, but it went far to undermine the authority of Surgeon’s Hall [of the Barber-Surgeons Company]."12

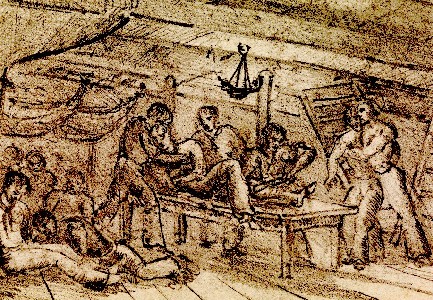

The Surgeon and His Mates at Work in the Cockpit During a Battle (1820)

The examination for the Navy's surgeon's mates (who could join at age 16) was about fifteen minutes long "and was very easy."13 Naval surgeon interviews were a bit more involved, requiring them to answer questions about their age, education, operations attended and knowledge of anatomy and surgery. "Perhaps one of the reasons for this somewhat lax interpretation of the duties of the company was the fact that for many years candidates for appointment to the services paid no examination fees - so the examiners were not paid and consequently spent as little time as possible over the formalities."14 Due in part to such cursory interviews, the navy "admitted as full surgeons men with no more than their apprenticeship completed who had not yet served as journeymen, and there must have been cases which fell short even of the seven years’ [apprenticeship] rule."15

Because of the nature of a surgeon's employment on a naval vessel, the 'operational necessity' sometimes extended to field promotions for surgeon's mates, who "could be raised to the rank of surgeon without having been before the Court of Examiners of the College of Barber-Surgeons, as was the normal practice."16 As a result, "in an emergency the navy might set aside all formalities and ‘qualify’ a surgeon without regard to any length of apprenticeship."17

Artist: Willem van de Velde the Younger

An English Sixth Rate Firing a Salute (1706)

Of course, the Barber-Surgeons Company did not look kindly upon the Navy circumventing their authority. In 1695, they "'complained that surgeons and mates are sometimes entertained by commanders of his Majesty’s ships, not qualified for the said office’." This was particularly directed at individual ship's captains, who "had been serving in the West Indies and North America."18 Although the navy had allowed the field promotion of surgeon's mate in 1665, this particular complaint was probably This was likely a result of instructions found in 'General Instruction to Captains', written in 1663 by the Duke of York. These instruction allowed a ship's commanding officer, master, boatswain and gunner to appoint inferior officers, giving them the ability to promote a surgeon's mate to surgeon "without examination and without reference to any guild or other authority ashore"19.

Such actions led to a deterioration in the training of ship's surgeons for the navy. The standard for surgery in England had been improved in the mid 17th century, increasing their status due in part to "the care with which their credentials were scrutinized, a development which also reflects the bureaucratic outlook of the day."19 However, the navy's need for surgeons and gradual degradation of the requirements for strict screening resulted in lower quality training and lesser qualified surgeons in the years following. Secretary of the Admiralty Burchett expressed concern for this in his book in 1703, noting that when sailors "happen to be Sick or Wounded, [they] Stand or Fall, in a great measure, by their Administration to them; and I have some Reason to doubt, whether there are many of the Ablest of our Sea-Chirurgeons, qualify'd to judge Nicely of many Distempers incident to a Sailer"20.

To make matters worse, an Act in 1698 which was designed to improve employment possibilities for navy men at the end of King William's War allowed soldiers to practice their trades "regardless of any failure to comply with the requirements of their craft guilds."21

William Cockburn's Book Sea Diseases

1736 ed, based on 1696 & 1697 editions

The term 'soldier' was understood to mean sailors as well and so the sea-surgeons were now given the ability to practice on land without concern for the rules and regulations of the Barber-Surgeon's Company. "Whatever may have been its justification as a relief measure and however welcome to individuals, the harmful effects of this legislation were soon felt by the guilds and even by less interested bodies."22

Of course, this didn't apply to all the surgeons at sea during this period, only those who had been incompletely trained, either through hospitals or premature promotions. Even diligent surgeons who had been promoted due to necessity had the opportunity to continue their education. As suggested previously, the amount of printed material available to them was quite extensive with books on nearly every relevant topic from medicine to diseases to fevers and fluxes to the various aspects of sea surgery itself.

The typical quality of training of the navy's surgeons did not necessarily represent the typical quality of training of the surgeons found on merchant ships. Not surprisingly, the best sea surgeons available to the merchant fleet would have been found on the best ships. Historian Peter Earle suggests that the East India Company's surgeons "were generally of higher quality than those serving in other merchant ships who were normally regarded as very lowly members of their profession."23 This had a direct impact on the quality of surgeons available to the pirates since it is from merchant ships that pirates abducted their surgeons. All things being equal, Indiamen were better protected while lesser merchantmen were not, so the quality of surgeon the pirates would have was not likely to have been the best trained or most qualified men at sea.

1 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 152; 2 James Yonge, The Journal of James Yonge [1647-1721] Plymouth Surgeon, p. 27-8; 3 Keevil, p. 152; 4 Dr. Kathleen Harland, "Naval Medical Care 1620-1770 Saving the Seamen: Naval medical care in the Pre-Nelson era, 1620-1770," J Royal Medical Service 2005, p. 65; 5 F.N.L. Poynter, "Introduction," Selected Writing of William Clowes, 1948, p. 14; 6 Zachary B. Friedenberg, Medicine Under Sail, p. 27; 7 Jonathan Charles Goddard, "An insight into the life of Royal Naval surgeons during the Napoleonic War, Part I, Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, Winter 1991, p. 215; 8 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, p. 25; 9,10 Keevil, p. 267; 11 Harland, p. 66; 12 Keevil, p. 152; 13,14 Sir Cecil Wakely, Surgeons and the Navy, transcript of Thomas Vicary Lecture delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in England, 11/14/1957, p. 279; 15 Keevil, p. 243; 16 Harland, p. 66; 17 Keevil, p. 152; 18 Keevil, p. 243; 19 Keevil, p. 150; 20 Josiah Burchett, "To the Reader", Memoirs of Transactions at Sea During the War with France, 1703, not paginated; 21,22 Keevil, p. 202; 23 Peter Earle, Sailors - English Merchant Seamen 1650-1775, p. 137