Royal Navy Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 <<First

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning Locations - Royal Navy Page 4

English Navy Outport Victualling Stations, Continued

Victualling Stores at Lisbon, Portugal

Similar to Port Mahon and Gibraltar, the English established temporary supply bases at Lisbon during the 17th century by agreement with the Portuguese.

Artist: Henry Perronet Briggs - Admiral Robert Blake (1829) It was briefly used to victual and water English ships in March of 1650 by Admiral Robert Blake when he attempted to get the Portuguese to give up refugee Royalist Prince Rupert of the Rhine. However, in an effort to pressure the Portuguese to give him Rupert, Blake blockaded Lisbon which eventually resulted in the English forces having to victual their ships at Cadiz, Spain during the majority of the blockade.1

In April, 1656, Blake was again able to establish a base at Lisbon, this time while blockading the coast of Spain at Cadiz.2 This was also an arranged affair with the Portuguese but seems to have had no victualling component; supplies were purchased as needed. Following a storm at Cadiz in March of the following year, Blake reported that some of the vessels in the blockade had received significant damage and much of their bread being spoiled. "And the frigates that came out last are so ill provided in twine, canvas and such like necessaries, that presently after their arrival they resorted to us for supplies, which we must buy at Lisbon or elsewhere as we can"3. He maintained the Cadiz blockade until June of 1657.

Lisbon was again considered for use as a base in the war with Algiers from 1677-83. John Narborough was sent to Algiers in October and he wrote the Admiralty that the fleet should be victualled at Plymouth or Portsmouth rather than in the Mediterranean.4 However, during a meeting of the Admiralty on November 3rd, 1677 they suggested using Lisbon to victual and refit ships because

Cartographer: Jacques Nicolas Bellin - Plan du Port de Lisbonne (1756) "his Majesty having a purpose of making use of that port during the present war with Algier, the chief seat whereof is likely to be in the mouth of the Straits"5. At a meeting a month and a half later, the Admiralty said in response to Narborough's letter that "stores of all sorts as well as provisioning, according to his Majesty's late resolution, [will] be lodged at Lisbon, and that the O[fficers of the] N[avy] be authorised to provide the same accordingly"6. The next day, they advised that Lisbon was "nearer and better than both [Plymouth and Livorno], where magazines of stores and provisions are designed to be lodged."7 However, the Admiralty backtracked three weeks later. "His Majesty was pleased, with the advice of the Lords, to declare his opinion that Port Mahon would be the properest place for the same [ship rendezvous and lodging stores], and that under the present silence of Sir J[ohn] N[arborough] our preparations by the Officers of the Navy should be directed thither."8 So Lisbon was swept aside as a victualling station in favor of Port Mahon at this time.

It received another opportunity to victual navy vessels when Tangier failed to live up to expectations in 1683. A

new campaign began against a group of Barbary Corsairs - the Sallee rovers - in 1684 and the

Artist: Willem van de Velde the Younger

Action Between an English Ship and Barbary Corsairs (late 17th/early 18th century)

victualling and supply base was moved to Lisbon during 1684 and 1685.9 Phineas Bowles served the role of victualling agent as well as storekeeper and muster master. However, "Bowles experienced great difficulty in acquiring suitable storehouses and had frequent disputes with the Portuguese authorities, problems that finally led the authorities to abandon Lisbon in favor of Gibraltar."10 Once again, another Mediterranean location was deemed preferable to Lisbon.

Lisbon served as an improvised forward victualling base one last time in this period beginning in 1704 when the Portuguese created an alliance with the British following George Rooke's success during the battle of Vigo Bay during the War of Spanish Succession. "This afforded Great Britain the use of Lisbon as a base — Lisbon, the finest harbour in the whole Peninsula."11 However, the English target was the French fleet at Toulon which was located far from Lisbon and it once again proved wanting. "[T]he difficulties of a strange language and of an alien system of weights and measures, the unpreparedness of the Portuguese and their lack of adequate supplies for a first-class fleet, their old-fashioned accommodation and their shortage of dockyard hands, made the place no substitute for an English base."12 As a result, the English fleet which had arrived in the winter of 1704 in preparation for the assault on Toulon was forced to return home.

Although Gibraltar was taken in 1704 and Barcelona, Spain was taken in 1705, neither proved very useful to England in their strategy at that time "and the allies were still forced to depend on the improvised resources of Lisbon."13 In 1705, Sir John Leake worked with the Portuguese to make the location more suitable with the establishment of a naval hospital, probably in a rented building.14 They almost certainly used rented buildings for storage, although "the Victualling Board was prepared to construct buildings, relying on the greater experience of Navy Board staff for assistance."15

A Fanciful View of the Port of Lisbon, Loading Ships With Supplies (18th Century)

At this time, Stephen Bisse served as the victualling agent, providing good service to the fleet. In December of 1706, Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovel wrote the Victualling Board,

Having frequently had very great experience of the care and dispatch of Mr. Bisse, your agent here, and he having given me fresh instances of it in my coming here now in his diligent compliance with my orders and his care and pains to procure fresh meat, which we have had for the whole fleet of men of war, and has been a great preservative and much contributed to the health of our seamen: I cannot omit to recommend him to your favour as a very good officer and deserving your countenance and encouragement. I understand that his allowances are very much short of what have been given to his predecessors abroad in these parts, and that his living here constantly ashore is very chargeable [expensive]. If there be room for your giving him further encouragement, I do believe he will not slacken his diligence, and that you will find he endeavours to deserve what favours you are pleased to show him.16

Bisse was still serving as Agent Victualler in 1710, having served there since early 1704 when a victualling base was established by the Victualling Board.17 Thomas Revell was appointed the victualling agent there in 1716.18

The English ceased to victual ships at Lisbon at the end of the war in 1713.19 The navy established a base there from 1779 to 1782 during the Anglo-French Wars (1778-1783) and and used it from 1783 until 1841 as a gathering point for English convoys.

1 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 198 & N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 4; 2 Rodger, p. 25; 3 Rodger, p. 26; 4 Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol IV, J. R. Tanner ed, 1903, p. 502; 5 Naval Manuscripts...", Vol. IV, p. 515; 6 Naval Manuscripts...", Vol. IV, p. 548; 7 Naval Manuscripts...", Vol. IV, p. 553; 8 Naval Manuscripts...", Vol. IV, p. 564; 9 Davies, p. 198 & Rodger, p. 90; 10 Davies, p. 198; 11,12 Geoffrey Callender, The Naval Side of British History, 1924, p. 136; 13 Rodger, p. 168; 14 Jonathan Coad, Support for the Fleet, 2013, p. 344; 15 Coad, p. 302; 16 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 279; 17 "46. Victualling Board to Secretary of the Admiralty, 4th July 1710," Queen Anne's Navy, Commander R. D. Merriman, ed., 1961, p. 296 & Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 16; 18 "Thomas Revell (d.1752), of Fetcham Park, Surr.",History of Parliament Online Website, gathered 11/5/20; 19 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Society in the Seven Years War, 2013, Translated Anita Higge and Michael Duffy, p. 63

Victualling Stores at Livorno (Leghorn), Italy

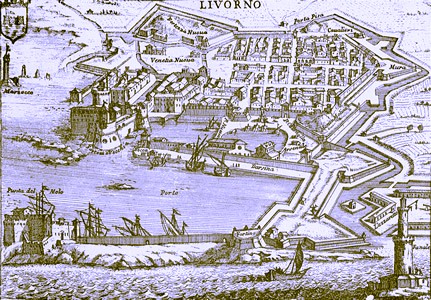

Livorno, Italy, often called 'Leghorn' by the English, was a convenient stopping place for English ships entering the Mediterranean. Unlike many other port cities, Livorno had been

Cartographer: Alexis Hubert Jaillot - Livorno and Its Location in Northern Italy (1708)

built with the needs of commerce in mind. Here vessels could get water, victuals and other supplies, have their ships cleaned and repaired and serve the necessary plague quarantine required to obtain pratique for use at other Mediterranean ports. English merchant ships began stopping at Livorno in the late 16th century and the navy began employing the port in the 17th. As early as 1597 an English counsel was appointed for the city.1

Historian J. D. Davies explains that Livorno "was an important port of call for most naval convoys that passed into the Mediterranean, and could also offer cleaning and victualling facilities for British fleets."2 It is not entirely clear when England established a storehouse there, but historian Michael Oppenheim notes that naval stores sent to the city via trader's ships around 1655 cost 50 to 54 s per ton to ship.3 In January of 1665, Alderman Sir Denis Gaudin, who had been directly involved in naval victualling since 1650, was contracted to supply victuals at Livorno for the year.4

In 1669, Thomas Clutterbuck, who was to have quite an impact on navy victualling in the Mediterranean, was appointed counsel in Livorno.5 In March of that year, Clutterbuck appears to have taken it upon himself to supply food to the English fleet. via 'his agent' Charles Longland. The navy captains refused to take these victuals, however, something Clutterbuck blamed on their "pretending they have no orders to receive them."6

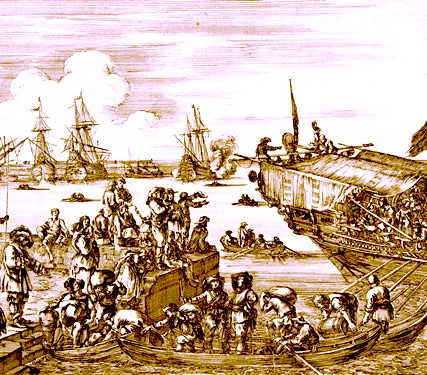

Artist: Stefano della Bella

Departure of a Galley From Livorno, Views of the Port of Livorno Series, The Met (1654-5)

Longland was a merchant who had been appointed as an English Admiralty agent in 1651 by the Council of State. "His duty was to report to the Council of State about ship movements in the Mediterranean and to assist in every possible way, even financially, the commanders of English warships arriving in the port of Leghorn."7 As part a long-time resident of the city and being fluent in Italian, he was in a unique position to provide news and information about the Mediterranean to the English government.

In early April of 1669, Captain Charles O'Brien arrived at the magazine at St. Peters (Forte San Pietro), reporting on the condition of the food stored there. He wrote the Navy Commissioners, "I made a survey of the victuals which had lain here 3 years, found the flesh just eatable, and gave order for shipping it off. The wine is good, and I doubt not but Mr. Longland may soon dispose of it. I shall perform your directions at Tangier."8 O'Brien brought the food to Tangier, but they didn't them so O'Brien to take them back to England. He explained, "I spent one week of the provisions for my own use, but was not able to spend more, by reason of the want of weight when boiled, one piece of 4 pounds when raw not weighing one pound when boiled ; and although I gave them double allowance, it caused great grumbling, and almost a mutiny."9

In addition to bad victuals, navy sailors could purchase food at Livorno when in port. While visiting the city aboard HMS Yarmouth in 1669, sailor Edward Barlow noted that they had

Map of Livorno (1781)

"plenty of fruits, as lemons and oranges, and roots, as onions and garlic in great plenty… and all manner of roots."10 Naval clerk John Baltharpe of HMS St. David reported that when they arrived at Livorno on their way into the Mediterranean in January of 1669. He notes, "When we had Prodick [pratique] got, Italian Jack Did furnish us with what we lack."11

As previously mentioned, when the navy was looking at Port Mahon as a victualling base in 1670, Clutterbuck recommended that victualling be performed at Livorno, since it was "the seat of trade and all supplies to be had upon reasonable terms"13. The navy still chose to move victualling to Minorca, a view Clutterbuck supported probably because he was going to be sending victuals from Livorno to the less capable Port Mahon.

In the 1670s, Clutterbuck became the resident naval agent at the port and by 1675 was the victualling contractor for the Mediterranean.13 It was usual for the agent at an outport to be a merchant who could find victuals locally as needed.14 A variety of other victualling agents served in addition to Clutterbuck including Longland (1652 - ~1660) and Robert Searle (~1684 -1686).17

Livorno had many connections to the navy during this period. Sir John Narborough’s fleet was victualled there in his battles with Tripoli in the Third Dutch War (1672-4). It was a difficult period for the English at Livorno, however. Near the end of the war, supplies were low and Grand Duke of Tuscany Cosimo III de’ Medici, "proved to be erratic and inconsistent in his attitude to British use of the port [and his] harbour authorities proved uncooperative"15. So the Admiralty chose to move their base to Malta, including £5000 of supplies which had already been shipped to Livorno from England.

This was hardly the end of Livorno as a victualling port, however. While aboard the HMS Assistance on August 13, 1676 waiting to obtain pratique at the port, Chaplain Henry Teonge reported that "they tell us that to-morrow we shall have provisions off."16 The ship was provisioned for the next three days,

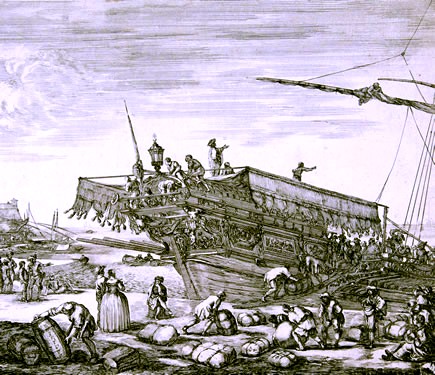

Artist: Stefano della Bella

Loading a Galley At Livorno, Views of the Port of Livorno Series, The Met (1654-5)

with Teonge specifically mentioning that his vessel took on water, bread and 'beverage wine' from Livorno. Narborough also used the port again for victualling his fleet, along with Port Mahon and Cadiz, in his expedition against Algiers in 1677.17

At the beginning of the War of the League of Augsberg in 1689, the majority of the provisions for the Mediterranean were sent to Gibraltar (700 men), but Livorno also received some provisions (75 men) with Smyrna and Alexandretta, Turkey bringing up the rear (55 men each).18 Near the end of the war in 1695, Livorno was still providing victuals to the fleet (which was maintained at Cadiz) while none of the other three locations were.19 (Neither of the Turkish locations seem to have been very important to naval victualling in the long term.)

Even after the war ended, Livorno remained an important stop for merchant vessels. "Between 1700 and 1730 the proportion of English ships entering the port rose from 34 to 80 per cent."20 While Livorno probably still served as an informal victualling base during this time, the capture of Gibraltar and Lisbon in the early 18th century and the establishment of bases there overshadowed much of Livorno's use as a victualling station. Victualling still continued to take place there, however. In the 1740s, the British Counsel at Livorno served as 'correspondents' who handled purchases on the ships' behalf, drawing bills of exchange on the Victualling Board.21

At its best, Livorno seems to have been a hastily assembled victualling port with some of its food being obtained locally by English merchants who lived there serving as agents.22 As with some of the other Mediterranean food depots, victuals were stored in existing buildings the Victualling Board rented by the Victualling Board.22

1 Matteo Giunto, "English Consuls at Leghorn", Leghorn Merchant Networks website, gathered 2/17/20; 2 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 198; 3 Michael Oppenheim, A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy, Vol 1, 1896, p. 345; 4 Davies, p. 201; 5 Giunto, gathered 2/17/20; 6 CSP Domestic Series, Oct.1668 - Dec. 1669, 1894, p. 226; 7 Stafano Villani, "A 'Republican' Englishman in Leghorn: Charles Longland," European Contexts for English Republicanism, 2013, p. 165; 7 CSP Domestic, Oct.1668 - Dec. 1669, 1894, p. 264; 7 CSP Domestic, Oct.1668 - Dec. 1669, 1894, p. 431; 10 Edward Barlow, Barlow’s Journal of his Life at Sea in King’s Ships, East and West Indiamen & Other Merchantman From 1659 to 1703, p. 163; 11 John Baltharpe , The Straights Voyage, or, St. Davids Poem, 1671, p. 32; 12 Calendar of State Paper, Domestic Series, 1670, 1895, p. 162; 13 Davies, p. 201 & Naval Manuscripts in the Pepsyian Library, Vol. IV, J. R. Tanner, ed., 1903, p. 4; 14 John Ehrman, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction, 1957, p. 156; 15 Davies, p. 198; 16 Henry Teonge, The Diary of Henry Teonge, Chaplain on Board H.M.’s Ships Assistance, Bristol, and Royal Oak, 1675-1679, 1825, p. 199; 17 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 90; 18 Survey of documents at British History Online (british-history.ac.uk), gathered 2/18/20 & Jonathan Coad, Support for the Fleet, 2013, p. 298; 18 John Ehrman, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697, 1953, p. 155-6; 19 Roger Morriss, The Foundations of British Maritime Ascendancy, Resources, Logistics and State, 1755-1815, 2011, p. 94; 22 Hugo Blake, "Livorno and the British - some notes", APM – Archeologia Postmedievale, 19, 2015. Italy and Britain between Mediterranean and Atlantic worlds: Leghorn – ‘an English port’, Hugo Blake, ed., 2017, p. 20; 21 Morriss, p. 292 22 Ehrman, p. 156; 23 Coad, p. 302

Victualling Stores at Jamaica

Jamaica was the only West Indies port which served as a true victualling station during the golden age of piracy. After Jamaica had been captured by Admiral William Penn's forces under General Robert Venables in 1655, naval ships remained there for the next few years, although vessels were gradually sent back to England.

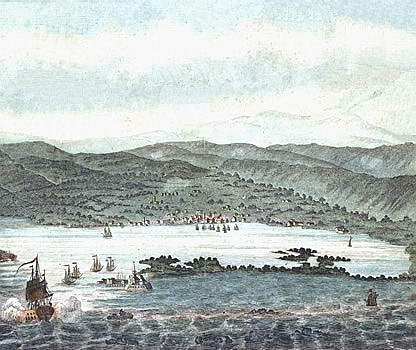

Artist: Alain Mallet - Ships Approaching Jamaica, From Description de L'Univer (1683)

The last two remaining ships - HMS Diamond and Hector - were sent home in 1660 by Colonel Edward D'Oyley 'for want of provisions.' "The result was that after about 1660 there were for a time no naval vessels in Jamaica, which had to rely on the dubious protection of privateers, and it was not until 1668 that the first regular guard-ship, H.M.S. Oxford, was assigned to the station."1 Between 1660 and 1668, naval supplies were ordered as needed by Naval Clerk Reginald Wilson, who provided them to visiting navy vessels. Merchant ships were also sent from England with supplies transported there for specific vessels.2 The shipping contracts for these vessels were drawn up based on a certain price per ton.3

An unnamed victualling agent was appointed at Port Royal, Jamaica in 1688, taking over Wilson's victualling duties.4 The agent was a private contractor responsible for meeting the needs of naval ships stopping, according to an established procedure.5 The Victualling Board of Commissioners had the agent manage the victualling warehouse at Jamaica, "to whom all captains had to report in order to obtain additional victuals."6

Much of the food for Jamaica came from the colonies in North America, primarily from Virginia and New York.7 . "The use of contractors in the Caribbean, in preference to the Commissioners’ practice of keeping stores under their control in domestic ports, was a recognition

View of Port Royal and Kingston Harbour in the Island of Jamaica (1778)

of the problems of supply over long distances. They employed merchants with the capacity to ensure the supply of provisions through well-established private connections throughout the Atlantic World."8 These merchants were the victualling agents, a variety of whom served in Jamaica during the Golden Age of Piracy including "Philip Rogers [16979], A. Wilson assisted by Hugh Gaine [1706-910], Samuel Younghusband [171611], Joseph Gyde [1706-171110,12,13,14] and Silvester Stuckley."15 In addition Thomas Wood served around 1705-1706.12 Note that the dates listed are approximate and the list is most likely incomplete, being based on what could be determined from official records.

In 1716, the navy changed tactics for victualling at Jamaica by establishing a dedicated naval supply agent at Jamaica in Kingston rather than relying on appointed merchants. This agent was referred to as the 'storekeeper.'16 It is not clear who first had the position, but by June of 1721, Samuel Holman was noted as being "Mustermaster and storekeeper at Kingston and Port Royal"17.

Victuals had been kept in warehouses on Port Royal since the English first established themselves there. "Port Royal

Map of Port Royal Before Earthquake, From The Gentleman's Magazine, Nov. 1785, p. 864

had been used as a base at intervals since the capture of Jamaica, but the Admiralty limited itself to hiring storehouses and making use of commercial careening wharfs until the great earthquake of 1692 shattered the town."18 When HMS Norwich wrecked on a reef just outside of Port Royal on June 17, 1682, some of its goods and provisions were sent to another ship while rest was sent "to 'captain Clark's storehouse' (probably the naval store)."19 A building identified as the 'King's storehouse' appears in a map of Port Royal on the land side of Thames Street20, but the navy seems to have rented the town experienced a huge boom in growth with the arrival of the buccaneers and the Spanish money they brought to the port making space there expensive. Before the earthquake, Port Royal contained than 60 acres which was increasingly divided and subdivided in the years leading up to 1692.21

Following the earthquake, the storehouses and wharfs the navy had rented slipped into the sea,

Artist: Jan Luyken and Pieter van der Aa - Port Royal Earthquake in 1692 (c. 1698)

along with many other buildings and 33 acres of land.22 Some attempts were made to rebuild, but much of the commerce moved to Kingston. The navy continued to use Port Royal until around 1726 when Vice Admiral Francis Hosier's squadron "found the facilities at Port Royal inadequate in terms of both storage and wharves."23 Although it had been rebuilt after the earthquake, the city was again destroyed by a fire in 1703 and then raked by hurricanes in 1712 and 1722, "effectively ending its commercial future. ...the disasters befalling Port Royal made the Admiralty understandably hesitant to invest in shore facilities, preferring to rely on the increasingly inadequate commercial facilities and storehouses in Kingston."24

Unfortunately, the Admiralty couldn't afford to build a large base in Jamaica at that time. It isn't clear when the navy first established permanent facilities in Jamaica, although a dockyard was proposed in 1732 which led to a careening wharf being built by May of 1735 and other structures used for ship repair being added by 1739. "By 1750, then , the major improvements were complete, and the dockyard had assumed the general appearance which it would retain for the next century. It was now well-equipped to receive ships after the transatlantic crossing, re-victual them, water them, refit them, and send them out on those Caribbean operations which were mounting in intensity."25

1 Michael Pawson and David Buisseret, Port Royal, Jamaica, 1975, p. 42; 2 Pawson and Buisseret, p. 47 & 48; 3 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Society in the Seven Years War, 2013, Translated Anita Higge and Michael Duffy, p. 136; 4 Pawson and Buisseret, p. 47; 5 Buchet, p. 63; 6 Buchet, p. 20; 7 Buchet, p. 137; 8 Douglas Hamilton, "Private enterprise and public service Naval contracting in the Caribbean 1720-50", Journal for Maritime Research, 2004, p. 39; 9 CSP Colonial, America and West Indies: 1696-1697, Item 1184; 10 Calendar of Treasury Books, Volume 25, 1711, 1952, p. ccxxxv; 11 Calendar of Treasury Books, Vol. 30, 1716, p. clxx; 12 Calendar of Treasury Papers, Vol. 3, 1702-1707, 1874, p. 421; 13 Calendar of Treasury Papers, Volume 4, 1708-1714, p. 277; 14 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 296; 15 Buchet, p. 134; 16 Morriss, p. 145, Pawson and Buisseret, p. 126 & Journals of the House of Commons, Vol. 17, From December the 7th, 1711 to August the 1st, 1714, 1808, p. 316; 17 The Parliamentary Register, Vol. 16, 1780, p. 524; 18 Jonathan Coad, Support for the Fleet, 2013, p. 210; 19 Pawson and Buisseret, p. 59-60; 20 Pawson and Buisseret, p. 84; 21 See Pawson and Buisseret, pp. 81-97 for a detailed description of how the land was used and ownership changed over time; 22 Coad, p. 252; 23 Roger Morriss, The Foundations of British Maritime Ascendancy, Resources, Logistics and State, 1755-1815, p. 145; 24 Coad, p. 252; 25 Pawson and Buisseret, p. 132