Royal Navy Provisioning Locations Menu: 1 2 3 4 Next>>

Golden Age of Piracy Provisioning Locations - Royal Navy Page 3

English Navy Outport/By Port Victualling Stations

While the top half of the chart below is devoted to English ports which were used as primary victualling stations, the

A Sampling of Navy Designated Victualling Stations Between 1665-1748,

Image Artist: Francis Holman - Blackwall Yard from the Thames (1784)

bottom half is focused on 'outport' and 'by port' victualling stations. Historian Paula Watson says that all of the Victualling Stations outside of London were considered 'out port' stations because they were supported by the Tower yard. Her 'out port' locations include Portsmouth, Dover, Plymouth, Chatham, Harwich and Kinsale, Ireland1. With the exception of Kinsale, all of these were discussed previously. She refers to the remaining victualling locations inn England, Ireland and Scotland as 'by ports' where "the board agreed with a contractor

to supply all the provisions that should be necessary for

such ships as might chance to call here."2 Her list of by ports includes Milford, Yarmouth, Lynn, Hull and Newcastle in England along with Dublin, Ireland and Leith, Scotland. At these locations, she explains that the contracts were "renewed every year, the contractor receiving a fixed rate calculated on the basis of the quantity of provisions supplied to one man for a day."3

These smaller yards were primarily storage yards, being supplied with food from London as well as through local contracts made by the agent contractor there. Victuals purchased locally by them were to be made at fixed rates set by the Victualling Board.4 Like the outports, these by ports could supply ships with the victuals specified on the navy menu: bread, peas, porridge, butter, cheese, vinegar and fresh beef (for those ships anchored at the port - so called 'petty warrant' victuals) as well as casks, biscuit bags and iron hoops for the barrels.5

Artists: Samuel and Nathaniel Buck - Southeast Prospect of Kingston Upon Hull (1745)

Ships sailing overseas were normally provisioned from a British port for a six-month supply of dry goods and salt meats and a three month supply of beer, butter and cheese from the European-based outports and by ports. They were then to be re-provisioned by victualling agents at established overseas locations or, where there were no such agents, by the ship's purser purchasing food at a local port market during much of the golden age of piracy. Because of the price differences and the potential for the pursers to cheat, resupply at the established overseas outport yards was preferred. Sometimes a fleet stationed too far from an established victualling yard was supplied by transport ships sent from the closest yard. A travelling victualling agent was then in charge of "organising bulk supplies of essential items such as water, fresh meat and vegetables which could then be collected by individual ships when convenient."6

The navy set up several English by ports with small storehouses during the Anglo Dutch Wars (1652-4, 1665-7 & 1672-4) including Milford, Yarmouth, Hull, Newcastle, Norwich and Lynn. As the Dutch Wars ended, so did much of the use of these locations for provisioning. Similarly, the victualling station located in Tangiers was abandoned by the navy shortly after the end of the Dutch Wars. (This is discussed in the sections on Port Mahon and Gibraltar.)

The northern European by ports were not thought to be effective by the Victualling Commissioners. Near the end of the War of Spanish Succession in March of 1711, they

Storehouses at the Woolwich Dockyard, From Survey of London, Vol 48, p. 85 (1698)

wrote that the queen would be better off "if no such contracts were made for victualling at by ports, but that her Majesty's ships should be supplied with provisions at those ports where there are agents and stores of her Majesty's provided for that purpose"7. They went on to complain that agreements were sometimes made by between the locally contracted agent and various ships' pursers to give them money in place of provisions.

In June of 1710, the Victualling Board added that local agent contractors sometimes set their own price on victuals "whenever they find (as it frequently happens) that no other person on the place besides themselves is either capable or willing to undertake the business ... and could heartily wish it were possible wholly to set aside these By Ports"8. To futher complicate the process, provisions sent to such by ports were sent via small, locally-contracted sloops called hoys who were paid for each voyage at varying rates per ton.9

1 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 86; 2 Watson, p. 94; 4 Douglas Hamilton, "Private enterprise and public service Naval contracting in the Caribbean 1720-50", Journal for Maritime Research, 2004, p. 38; 6 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Society in the Seven Years War, 2013, Translated Anita Higge and Michael Duffy, p. 105; 7 '30 Mar- 1711, Adm 110/5', cited in Watson, p. 96; 8 'Victuallers to Burchett, 23 June 1711, Adm 110/5', cited in Watson, p. 96;9 Watson, p. 97

Overseas Victualling Stations for the English Navy During the Golden Age of Piracy

Artist: Balthasar Friendrich Leizelt - Loading a Ship at Salem, MA (c. 1770)

Naval victualling could technically occur at any port where a contractor would accept English navy credits, although the Victualling Board normally arranged for this with particular victuallers in selected ports. During the War of Spanish Succession, ships in the northern part of North America victualled their ships with a contractor on the New England coast at the rate of 7 pennies a day, based on a deal made by the Victualling Board in 1703.1 Similarly, arrangements were made on a percentage baseis with contractors in places like Barbados, Livorno and Genoa.2

However, the Board preferred having more control, which was done by setting up foreign victualling locations. With this in mind, the rest of this article are the non-English victualling sites which in use during the golden age of piracy. Of these sites, only Kinsale, Ireland (technically an English site during this time) appears in every period shown here. Gibraltar was consistently used after it came under British control in 1704 as was Port Mahon in Minorca, Spain when the British captured it in 1708. Other widely used ports were were at Dublin, Ireland and Jamaica. Each of these were in use in the period of interest.

1 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 179; 2 Watson, p. 179 & 182

Victualling Stores at Kinsale, Ireland

A victualling office with an established agent was established at Kinsale in 1650 to provision the English Men-of-War which patrolled the coast during the

Artist: Charles Price - Kinsale Map with Storehouse Location Shown (1741)

Irish Confederate Wars (1641-53).1 Admiralty records refer to a yard there in February of 1660, although little is known about these facilities, which may have been only temporary."2 A victualling agent for the navy was sent in 1683 by the Victualling Board, which was "the first step to creating permanent naval facilities in southern Ireland."3

This was a small victualling and store depot which "could carry out light refits of the smaller ships, and be expanded in time of war. The usefulness of Kinsale was limited by a shoal that blocked the harbour entrance, preventing the passage of anything above a 4th-rate"4. Kinsale became a cruiser base in 1694, although the ship size limitations prevented a large dockyard from being built there.5 "In the 18th century more permanent depots were established ...primarily intended for victuals, [and] ships' equipment"6.

Daniel[l] Whittfield was assigned to Kinsale as the station's Victualling Agent by the Victualling Board in December of 1683.7 By 1710, the Board reported that Francis Whitworth had been employed there as Agent Victualler since January of 1704, probably serving as storekeeper as well at this small station.8 Kinsale was used as a depot for stores and victuals until 1748. However, due to its strategic location, it continued to be used during wars after that, eventually being moved to Hawbowline Island near Cork.9

1 Elaine Murphy, Ireland and the War at Sea, 1641-1653, 2012, p. 84; 2 Jonathan Coad, Support for the Fleet, 2013, p. 396; 3 Coad, p. 20; 4 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 102; 5,6 Coad, p. 20; 7 His Majesty's Stationery Office, Calendar of Treasury Books, Volume 7, 1681-1685, 1916, p. 968 & 1370; 8 "46. Victualling Board to Secretary of the Admiralty, 4th July 1710," Queen Anne's Navy, Commander R. D. Merriman, ed.,1961, p. 296; 8 Roger Morriss, The Foundations of British Maritime Ascendancy, Resources, Logistics and State, 1755-1815, p. 284

Victualling Stores at Dublin, Ireland

Dublin was a local store yard, kept for ships operating in the western fleet, 'in both war and peace'1. As early as the 1630s, Captain William Brooke was surveying Irish

Artist: John Roberts - A South View on the River Liffey, Dublin, British Library (1807)

ports and writing about which could serve as good victualling sites. He said, "Dublin is a faire bay on the north parte thereof is the barr as you see in the Mapp, this is a great cittie and rich, the seate of the Lord Deputey. ...this is a plentifull countery & able to victual yor Mai[jes]tes shipps."2 However, Brooke also warned that "its noe place for yor Mattis great shipps."3

By the 1680s, Dublin had a victualling agent. Some of its supplies may have been purchased locally, but most of them came from Tower Hill in London.4 During the War of the League of Augsburg (1689-1697), the victualling agent at Dublin was ordered to purchase enough victuals to supply forty men-of-war in an effort to circumvent English victuallers who wanted cash payments in lieu of credit. The target was quickly increased to forty-five ships. "The experiment was not a success. Not only were Irish victuals more expensive than English, but according to the ships their quality was worse."5

A victualling agent must still have been stationed at Dublin during the War of Spanish Succession (1701-14)

because the officers and foremast men on HMS Charlotte wrote the Lord High Admiral to complain about the food he supplied. They said that "of late, your petitioners have been ordered to take

Artist: John Peter Laporte - Dublin Bay as Seen from Clontarf, British Library (1796)

their provisions from the Agent for Victualling at Dublin; [and] though the victuals of all kinds are now at very reasonable rates, yet your petitioners receive constantly such as are salt and, for the most part, not good in their kind."6 They asked if they could instead be given funds to purchase fresh victuals as they had done in the past. The port must have been busy during the war because a second victualling agent was sent to Dublin in 1710.7

By 1715, after the war had ended, the Victualling Commission decided to work with private contractors who could supply a much food as was requested of them at set prices in locations were the ship traffic was not enough to warrant a victualling yard. Such a procedure was put in place at Dublin in October of 1716. It is not clear that a victualling agent was involved in these proceedings, although historian Christian Buchet says that ship's captains dealt directly with the contractors, so it seems unlikely. A similar arrangement was made in the months following at Barbados, New England, New York, Virginia and Maryland.8

1 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 200; 2,3 Arnold Horner, "'Ireland's true survay', 1630s", History Ireland, Vol. 26, No. 5, Sep 2018, p. 26; 4 John Ehrman, 1957, The Navy in the War of William III 1689-1697: Its State and Direction, p. 155; 5 Ehrman, p. 593-4; 6 Commander R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 259; 7 Merriman, p. 249; 8 Christian Buchet, The British Navy, Economy and Society in the Seven Years War, 2013, Translated Anita Higge and Michael Duffy, p. 21

Victualling Stores at Leith, Scotland

Leith was an outport victualling location set up after the Union with England in 1707. Like other larger outports, it was run by an agent who was also storekeeper.1 This was to victual a squadron which had been sent to Leith in 1709 by the Lord High Admiral, remaining based there throughout the War of Spanish Succession.2 Little else is said about this site, although a complaint about the food available at Leith was made.

Leith Pier and Harbor (1798)

On December 18th of 1708, the Victualling Board wrote to the Secretary of the Navy about the provisions at Leith where "Mr. Douglas... is under contract with us to furnish her Majesty's ships with provisions"3. This is clearly more of a contractor-agent position than a navy Victualling Agent. The letter goes on to explain,

as this is the properest season of the year for providing all species of provisions, and Leith being so near Edinburgh, we are very much concerned to hear complaints of this nature. But since Captain Boys has informed [the Lord High Admiral] that the provisions there are bad as well as scarce, we know of no way of remedying the same at present, except his Lordship would be pleased to direct their victualling at Newcastle, where we conceive provisions sufficient may be provided for that squadron as well as for the coast convoys, if the ships are capable of taking the same from thence in the winter season.4

The problem must have been straightened out because the Leith provisioning station remained opened until May 1st of 1713 when the Admiralty told the Navy Board that the salary of the 'storekeeper' (victualling agent John Colquitt5) was to be stopped since the war had ended.6

1 R.D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 249; 2 Steve Murdoch, The Terror of the Seas?: Scottish Maritime Warfare 1513-1713, 2010, p. 306; 3,4 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 287; 5 Calendar of Treasury Books, Volume 27, 1713, 1955, p. clxvii; 6 Merriman, p. 50

Victualling Stores at Gibraltar

Gibraltar was considered as a possible base for naval operations in the first half of the 17th century. "[A]s early as 1625, when Britain was at war with Spain, it had been suggested that Gibraltar should be captured and used as a base."1

Artist: Joannes Covens and Cornelis Mortier - De Haven en Straat van Gibraltar (1730)

At that time, it was noted to be "a small place ...the easier to be manned, victualled and holden ... once taken"2. Its capture for use as a base was again discussed in 1656, but decided against due to a lack of troops which would be necessary to take it because of the strong defenses the Spanish had put in place.3 Interest in Gibraltar waned when Tangier was acquired in 1661 through Charles II's marriage to Catherine of Brazanga. Tangiers proved to be a difficult location to protect and use, however, so "successive commanders in chief based their operations in the Mediterranean almost anywhere except Tangiers."4

It was first used by the English as a base for eighteen months beginning in December 1680 by Arthur Herbert, Commander of a Squadron assigned to protect Tangier from corsairs, when he became frustrated with Tangiers. Herbert wrote the Admiralty Secretary John Brisbane that Gibraltar "lies so conveniently for discovery [of enemy vessels] at all times, in clear weather we can see ships either to the eastward or westward, before they come within seven miles of the place."5 He also told Brisbane he wished there were "some stores lodged at Gibraltar, as likewise a quantity of provisions for victualling the ships. For that port is so commodiously seated for cleaning and victualling that it would be of great advantage in giving a dispatch to our frigates"6. During this period victualling was performed at the Rock, although the victuals remained at Tangier and the Victualling Board had to pay extra to ship them to Gibraltar.7

Gibraltar, Its Fortifications and Improvements (1735) |

Gibraltar was officially used as a victualling base between 1685 and 1689 thanks to the Anglo-Spanish alliance during the War of the League of Augsberg.8 However, the Spaniards would not grant the English permission to put their naval victuals in town, so the appointed Agent General for the Affairs of the Navy at Gibraltar Jonathan Gauden was only permitted to put storehouses in a location he described as "so near the weather side that the surf of the sea will, in foul weather, beat up to it, so that from that inconveniency and moisture of the air in that place, many of the goods will perish and be rendered altogether unserviceable."9

Gauden was the son of victualler Sir Denis Gauden, who was the contracted victualler for the navy between 1660 and 1677.10 Jonathan was heir to the family business and had previously served as one of the contracted victuallers to in Tangier between 1678 and early 168411, so it is likely he was a contracted victualler here during this period as well rather than a navy employee. They must have made this situation work in some way for no further mention appears of the problem during the remainder of Britain's use of Gibraltar during this period.

During the War of Spanish Succession, the Dutch and English captured Gibraltar in 1704 when the Grand Alliance Fleet

Artist: Pieter Sluyter - Conquest of Gibraltar by the Anglo-Dutch Fleet (1704-5)

led by George Rooke, "launched its attack almost on the spur of the moment, following the abandonment of a vague project against Cadiz."12 Because of its location, Gibraltar had to be entirely supplied with food by sea until trade with Spain could be resumed.

Like many important English overseas victualling locations, a victualling agent handled provisioning at the Rock during this period. Benjamin Bowles served as Victualling Agent between at least 1707 and 1709.13 Alonzo Vere took over this position for Bowles in October of 1709, serving at least until 1710.14

The new mole (pier) there could only handle English naval vessels up to 4th and 5th rate, and those only one at a time. This made it slow and difficult to supply and repair ships. In addition, a "chronic shortage of appropriate storage was to bedevil operations from Gibraltar in the first half of the eighteenth century; permanent storehouses were not completed until 1746."15 This point was raised by the victualling board in December of 1708 who noted that "a great quantity of bread lain in store there which ...is damnified and decayed for want of good storehouses"16. In fact, no new buildings were put up by the navy at all until some sheds and storehouses were constructed near the new mole for naval stores.17 Its greatest strength to the English was its location which made it a good stopping point on the way to Port Mahon (captured in 1708) and a good place to prevent France and Spain from sailing from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic.18 Gibraltar contained a British naval dockyard until 1984 and is currently a possession of the United Kingdom.

1 Jonathan Coad, Support for the Fleet, 2013, p. 209; 2 Peter Le Fevre, "Gibraltar, Tangier And The English Mediterranean Fleet 1680-1690", Gibraltar as a Naval Base and Dockyard, 2000, p. 52; 3 N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, A Naval History of Britain, 2006, p. 14 & Le Fevre, "Gibraltar, Tangier And The English Mediterranean Fleet...", p. 14; 4 Rodger, p. 90; 5 Peter Le Fevre, :"Arthur Herbert, Earl of Torrington, 1648 - 1716", Precursors of Nelson: British Admirals of the Eighteenth Century, 2000, p. 25; 6 Le Fevre, "Gibraltar...", p. 22; 7 Le Fevre, "Gibraltar...", p. 24-5; 8 J.D. Davies, "Gibraltar In Naval Strategy c.1600 – 1783", Gibraltar as a Naval Base and Dockyard, 2000, p. 11; 9 Le Fevre, "Gibraltar...", p. 28 & His Majesty's Stationary Office, Calendar of Treasury Books, Volume 8, 1685-1689, William A Shaw, ed., 1923, p. 593; 10 "Alderman Sir Denis Gauden (Navy Victualler)", The Diary of Samuel Pepys website, gathered 2/5/21; 11 Calendar of Treasury Books, Volume 8..., p. 317; 12 Davies, p. 3; 13 Office-Holders in Modern Britain: Vol 4, Admiralty Officials 1660-1870, J. C. Sainty ed., BHO Website, gathered 2/3/21; 14 "46. Victualling Board to Secretary of the Admiralty, 4th July 1710," Queen Anne's Navy, Commander R. D. Merriman, ed., 1961, p. 296; 15 "37. Lord High Admiral to Navy Board, 27th December 1708," Queen Anne's Navy, p. 287; 16 Davies, p. 14; 17 Richard Harding, "Gibraltar: A Tale Of Two Sieges 1726-7 and 1779-1783", Gibraltar as a Naval Base and Dockyard, 2000, p. 26; 18 Davies, p. 12

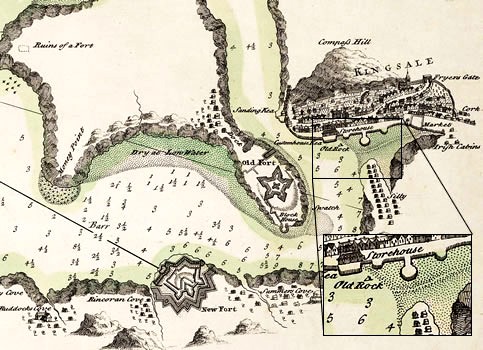

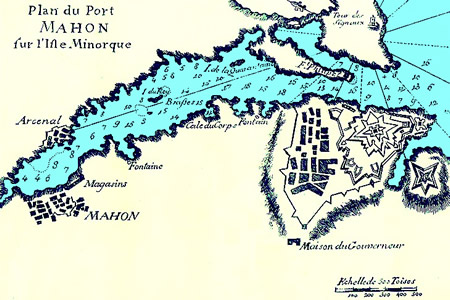

Victualling Stores at Port Mahon in Minorca, Spain

The history of the Port Mahon victualling site in Minorca was similar to Gibraltar. Sir Thomas Clutterbuck, the victualling agent at Livorno, Italy (called 'Leghorn' by the English) in 1670 stated in April that his site was preferable because

Artist: John Thomas Serres - Port Mahon, Minorca with British Men-of-War (c. 1795)

it was "the seat of trade and all supplies to be had upon reasonable terms, which will never be found at Port Mahon"1. However, by October, Clutterbuck wrote the Naval Commissioners, "I attend your full and effectual reply to my proposition as to victualling his Majesty's ships at Port Mahon."2 Like Gibraltar, an Informal arrangement encouraged thought the giving of 'gifts' to the local governor was made to use Port Mahon as a victualling and repair location for the English Navy on October 28th, 1670.3

At that time, Richard Gibson was appointed to be victualling agent at Port Mahon, although he likely served in a merchant-victualler capacity. On November 17, he reported, "I have been viewing conveniences for the hiring of houses for the stowage of stores, buying and issuing wine, and unloading the victualling ships, so as to save demurrage [the fee paid to a hired ship for leaving cargo on board]."4 By January of 1671, Gibson was building a structure "capable of receiving 200 tons of provisions... upon the [Castilian] King's ground near the waterside (to ease the charge and difficulty of transportation [to ships], and to secure it from thieves)"5. He was using caves to store the goods and explained that he had been directed to build at the port because there was only space for two months provisions when he arrived.6

Included in documents sent by Gibson to the Navy Commissioners was a letter from Vice Admiral Sir Edward Sprague. In it Sprague complained, "His Majesty has made this place a victualling port, and appointed [Gibson] to provide and issue the provisions sent there for the use of the fleet under my command; but I find that, through a defect in one species of victuals, the remaining sorts are thereby rendered unuseful, to the shortening the whole for the time the defective fall short"7. Although Sprague does not identify which 'species of victual' had gone bad, Gibson continually had problems with the bread.8 The temporary navy victualling station ceased operating in January of 1672, with all the stores being removed on the 12th.9

British victualling returned to Port Mahon in 1708 after General Stanhope's forces captured Minorca and Port Mahon surrendered on September 30th. "Port Mahon possessed everything that Gibraltar lacked: a superb natural harbour, shielded from the elements; a town with space in

Cartographer: Joseph Roux - Plan du port Mahon sur lisle Minorque (1804)

The British Naval Base on the North Side of the Harbor Is Probably the 'Arcenal'

which to expand a dockyard infrastructure; a substantial hinterland; and an excellent strategic location"10. The British began their occupation by renting storage locations and a convent which they converted into a naval hospital. Victualling agent Joseph Gascoigne was appointed as storekeeper on January 19th, 1709.11 All the naval victualling supplies were initially sent to Port Mahon from England even though it was known that, between the time gathering and loading them and the time shipping them, they were often stale by the time they arrived. Gascoigne soon "discovered that he could buy bread,

peas, oatmeal and corn locally. As the islands had windmills and

fuel, a furner and four bakers were sent from England. Eventually

the only product which had to be sent from England was meat."12

Problems occurred with patients because the hospital was so close to taverns in the town. To solve this, Admiral Sir John Jennings had a new hospital built in 1711 away from the town. Vice-Admiral John Baker established a naval base on the north side of the harbour in 1715, rebuilding a old careening wharf which was there and using the empty rooms in the new hospital for stores. The abandoned convent was given to the Victualling Agent and a cooperage for assembling casks was built next to it.13

"Not surprisingly, Mahon and not Gibraltar became the lynchpin of British Mediterranean strategy for the first half of the eighteenth century."14 At the beginning of the War of Jenkins Ear (1739-48) the small yard Baker had built was improved with the addition of storehouses, refitting of the facilities and addition of staff.15 The English lost Port Mahon to the French in 1756, but they returned it in 1763. It was lost and regained by the English twice more before they finally returned it to Spain in 1802.

1 Calendar of State Paper, Domestic Series, 1670, 1895, p. 162; 2 CSPDS, 1670, p. 500; 3 J. D. Davies, Pepys's Navy, 2008, p. 24 & CSPDS, 1671, 1895, p. 251; 4 CSPDS, 1670, p. 533; 5 CSPDS, 1671, 1895, p. 17; 6 CSPDS, 1671, p. 111; 7 CSPDS, 1670, p. 536; 8 See CSPDS, 1671, p. 111, 158 & 455; 9 CSPDS, December 1671 to- May 17th 1672, 1897, p. 86; 10 J.D. Davies, "Gibraltar In Naval Strategy c.1600 – 1783", Gibraltar as a Naval Base and Dockyard, 2000, p. 12; 11 R. D. Merriman, Queen Anne's Navy, 1961, p. 296; 12 Paula K. Watson, "The Commission for Victualling the Navy, the Commission for Sick and Wounded Seamen and the Prisoners of War and the Commission for Transport, 1702–1714," University of London PhD thesis, 1965, p. 179; 13 Jonathan Coad, Support for the Fleet, 2013, p. 238; 14 Davies, p. 12; 15 Roger Morriss, The Foundations of British Maritime Ascendancy, Resources, Logistics and State, 1755-1815, p. 144