Portable Surgical Kits Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

Portable Surgical Kits From the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 4

Plaster Box and Pocket Kit Instruments - Plaster Box & Pocket Kit Continued

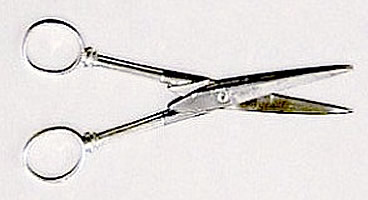

13. Scissors

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, Peter Lowe, Felix Würtz, John Woodall, Thomas Brugis & Randle Holme

Scissors were another common item, being mentioned by six of the eight authors who discuss

Photo: © Dr. Robert Greenspan, Used with Permission

Portable Scissors from an 18th Century Surgeon's Pocket Etui, From

CollectMedicalAntiques.com the contents of their portable surgical kits. However they appear to have been so common that, like the razor, they aren't discussed much by period surgical authors. Sea surgeon John Woodall advised his readers that "a carefull and especiall respect [is] to be had concerning Sizers"1, probably referring to the need to keep them in good condition and working order. He elsewhere recommends that the surgeon's mates [assistants] were to make sure that the scissors were "well ground [sharpened], and kept cleane"2.

Scissors could be made from a variety of materials. William Fabry mentions that he had a pair made "by a skilful Artist in Silver, which I used only within the Town, Patients being less afraid of them than of Iron."3 However he goes on to recommend that ship's surgeons should not have silver scissors, rather instead having them be "very conveniently made of Iron or Steel"4. Although he does not specifically say so, his concern was probably that they would be stolen in such an environment. Good scissors were expensive to make and hard to keep sharpened. A detailed discussion of this can be found in the barbering article.

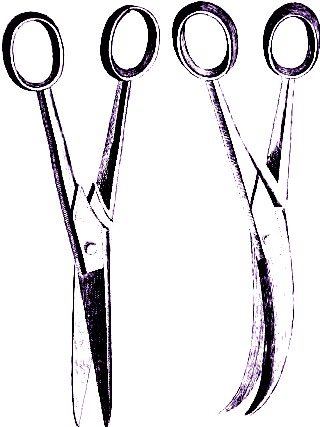

Scissors in Pocket Kit from A General System of Surgery

in Three Parts, By Lorenz Heister (1750) When describing the instruments found in his pocket kit, Lorenz Heister mentions "a pair of strait Scissors, fit for many Uses; the Surgeon should have several pair of these at home, of different sizes." He also suggests the inclusion of a pair of 'crooked Scissors'.5

One of the most obvious uses of scissors was for cutting hair when the ship's surgeon had assumed his role as barber. However, the pocket kit scissors were likely too small to function effectively in such a role. They were more likely used to cut dressings. In his discussion of pocket instruments, English surgeon Thomas Brugis notes that they are "very useful to cut Cloth for Rolers, Lint, and Emplasters"6. Fellow English surgeon James Cooke concurs.7

Both Lorenz Heister and Brugis note that small scissors were sometimes useful in cutting the skin. Brugis explains that they could be used "to cut, and clip off loose Skin, putrid or superfluous Flesh, &c."8 Heister advised that the curved scissors in the portable kit were "proper to be used in dividing Fistulæ, and in many other Cases."9

Although none of the surgeons discussing their pocket kits mention cutting sutures with small scissors, French surgical Pierre Dionis recommends them in this capacity.10 A full account of his comments can be found in the article on suturing.

1,2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 25; 3,4 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus, aka. William Fabry, Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, p. 23; 5 Lorenz Heister, A General System of Surgery in Three Parts, 1750, p. 11; 6 Thomas Brugis, Vade Mecum, 1689, p. 4; 7 James Cooke, Supplementum chirurgiae and the Military Chest, 1655, p. 418; 8 Brugis, p. 4; 9 Heister, p. 11; 10 See Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., page 42 & 48

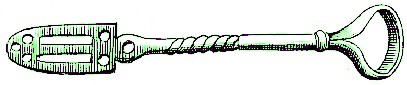

14. Spatula

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, Peter Lowe, Felix Würtz, John Woodall, James Cooke, Thomas Brugis & Randle Holme

Spatulas were another widely supported instrument in portable surgical kits, being included by seven of the eight authors who detailed the contents of such kits. Sea surgeon John Woodall states that the surgeon should have a variety of them because "they cannot be forborne in the [surgeon's] chest."1 He is talking in that particular quote about a large, non-portable instrument chest or of the instruments found in his medicine chest. However, he also recommends having one in the portable plaster box.2

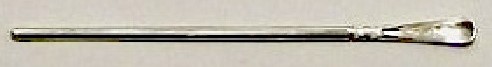

Simple Spatula, From Cours d'Operations de Chiurgie, By Pierre Dionis, p. 15 (1708) The spatulas basic design was fairly simple as can be seen from the image at left. This is taken from the instructional text by Pierre Dionis, one of the few surgeons to actually describe a spatula in any detail. "It ought to be strong, broader at one end than the other, flat on one fide, and half round on the other"3. He goes on to declare, "Those Chirurgeons who are somewhat nice, have them always of Silver rather than Iron, which is never so perfectly clean [as silver], and which fouls their Hands more than the other."4 Woodall advises that "the Artist may make wooden splatter [spatula] which will be farre fitter and cleaner than those of Iron, and [yet] the Surgeons chest cannot well be without both sorts"5.

Spatula with Hook Opposite, From Mellificium Chiurgiae, By James Cooke (1693) For portable surgical kits, surgeons often used spatulas designed so that the end opposite could perform some other function. Such designs would save space in their portable kits. For example, James Cooke shows one with a curved hook on the opposite end, explaining that it would be useful "in removing filth hardened [in the wound], and to remove plaisters if the one end be crooked."6 When discussing small forceps (or tweezers),

Spatula with Pincers Opposite , From A Discourse in the Whole Art of

Chyrurge,

By Peter Lowe (1612) Randle Holme said the 'broader end' of them "will serve to spread Plasters on linnen cloth, or leather, for want of a Spatula."7 Surgeon Peter Lowe actually shows a pair of tweezers apparently designed with this purpose in mind. (Seen at left.) The were sometimes coupled with the spatula lingua (discussed in the next section), such as the one found below.

Photo: © Dr. Robert Greenspan, Used with Permission - Spatula Lingua/ Regular Spatula, From the Etui Pictured at CollectMedicalAntiques.com |

The main function of a spatula involved medicines. Lorenz Heister says, "These are chiefly used in spreading Plasters, Ointments, and Cataplasms"8. This function is repeated by the most of the other surgeons who comment on the spatula.9

Normal Single- and Double-Ended Spatulas from A General System of Surgery

in

Three Parts, By Lorenz Heister (1750) Thomas Brugis notes that it can be used "used to mingle your Unguents on your palm of your hand"10. Cooke explains that it is "to take out unguents out of the Salvatory" in order to spread them on plasters.11 Woodall adds that they can also be used "to stirre about, and the better to compound any medicine on the fire"12. None of these added details venture very far from the spatulas' normal purpose.

The one author to mention using a spatula as a non-medicinal surgical tool is Lorenz Heister who suggests that "sometimes with their fulcated [falcated – curved] Extremity they are of service in raising up fractured Bones of the Cranium."13 Surgery on the skull normally involved the use of a wide variety of surgical instruments which were tailored to the operation, so this must have only been done when the surgeon did not have ready access to such tools.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 14; 2 John Woodall, "The particulars of the Surgeons Chest", the surgions mate, 1617, not paginated; 3,4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris, 1710, page 15; 5 Woodall, p. 14-5; 6 James Cooke, Supplementum chirurgiae and the Military Chest, 1655, p. 421; 7 Randle Holme, The academy of armory, Book III, 1688, p. 425; 8 Lorenz Heister, A General System of Surgery in Three Parts, 1750, p. 12; 9 See Thomas Brugis, Vade Mecum, 1689, p. 4, Woodall, p. 26, Dionis, p. 15, & Cooke,p. 421; 10 Brugis, p. 4; 11 Cooke, p. 421; 12 Woodall, p. 13, 13 Heister, p. 12

15. Spatula Lingua

Included by: William Fabry, James Cooke, Thomas Brugis & Randle Holme

The spatula lingua is included by three authors in plaster boxes and by one in a pocket kit. The pocket kit which includes it is described in William Fabry's text. That text mis-names it as a Speculum oris (a tool which is used to mechanically pry the mouth open), although the description of its use clearly refers to a spatula lingua.1 Given that this tool is also called a speculum lingua by John Woodall and James Cooke, the confusion on the part of the author (or, more likely, the translator of Fabry's original work) is understandable.

The spatula lingua has two ends, one to hold

Speculum Lingua, From l' Arcenal de Chirurgerie, By Johannes Scultetus,

Table 11 (1712) the tongue down and the other to scrape it. The end used to push the tongue down is referred to by Thomas Brugis and John Woodall as a spatula because of its shape. He notes that it is "perforated and cut through, the better to hold the tongue down without slipping off"2. William Fabry explains that the spatula end is used "in affects [health problems] of the Jaws and Throat, [and ] to depress the tongue"3.

Woodall explains that the scraping end is "very fitting in fevers, and furring of the tongue"4. The purpose of holding the tongue down is fairly straightforward. Various authors explain it being used "in case of sores, or other distempers ariseing from inward causes"5, "to see affects of the mouth and throat"6 and

Spatula Lingua, From Mellificium Chiurgiae, By James Cooke, p. 117 (1685) "when you inject any liquor into the throat, or apply any medicine to the mouth or throat, or when you would make inspection into the mouth or throat in any affects of the Uvula, or in Squinancies [peritonsillar abscesses, behind the tonsil], Cankers, or Excoriation of the mouth or gums."7 Woodall notes that some people use a regular spatula, but he advises that the perforated end of the spatula lingua "is farre steddier, better, and cleaner; and being through hollow, as is said, the tongue is not apt to flip or slide from under it any way."8

1 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus, aka. William Fabry, Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, p. 23; 2 Thomas Brugis, Vade Mecum, 1689, p. 6-7; 3 Fabry, p. 23; 4 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 9; 5 Randle Holme, The academy of armory, 1688, p. 426; 6 James Cooke, Supplementum chirurgiae and the Military Chest, 1655, p. 422; 7,8 Woodall, p. 9

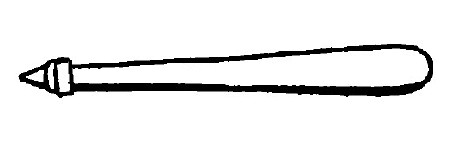

16. Stitching Quill (Cannula)

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, William Fabry, Peter Lowe, John Woodall, James Cooke, Thomas Brugis & Randle Holme

The stitching quill or cannula is found in the texts of seven of the eight surgeons writing about pocket kits and

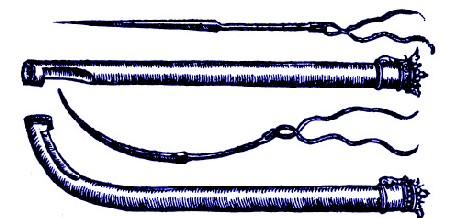

Straight & Curved Needles and Cannulas, From The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose Pare, p. 256 (1649)

plaster boxes, making it another of the popular instruments carried by a surgeon. Sea surgeon John Woodall says that the "stitching quill, & stitching needles have their due place in the plaster box; wherefore, that they may be the more ready on the suddaine as occasion is offered"1.

It is basically a hollow tube that is sealed on one end with an eye-like ring extending from that end. It is open on the other with a cap to seal it. Both French surgeon Ambroise Paré and his student Jacques Guillemeau show images of stitching quills with one being curved and the other being straight.2 French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis advises that the stitching quill should be "rather curve[d] than straight"3. Yet most stitching quills, such the one shown in James Cooke's book Mellificium chirurgiae (seen below right), are straight.

A Stitching Quill Which Could Double as a Burras Pipe, From Mellificium

chiurgiae,

By James Cooke, p. 117 (1685)

Dionis is the only author under study from the era to mention a material for the instrument: "The Tube ought to be of Silver"4. Historian John Kirkup describes a portable kit in the possession of the Royal College of Surgeons in London dating to 1674 which contains "[a]n excellent silver stitching cannula"5.

The stitching quill had two purposes and they are mentioned by just about every author who describes them. James Cooke notes that "the first is to preserve the needles in"6. In fact, this function is important to its design; William Fabry explains that "it ought to be of that length, as to contain the Needles within its hollowness"7. This is why one end of the tube was left open and capped. The needles could be placed inside and sealed there so they wouldn't get lost or damaged among the other instruments in the pocket kit or plaster box. One drawback of the cannula was that it could only accommodate straight needles.

Photo: Peter J. Goebel

Brass Stitching Quills Reproduction, Goose Bay Workshops LLC

The closed end of the stitching quill/cannula was designed with a ring and a sloping surface for the other purpose of the quill - to help in stitching up wounds. Woodall describes how it is used. The ring is "to be set to the one side [the side opposite where the needle is to be inserted] of the lippes or sides of the wound which you intend to pierce, so that it may give a stay to the part when it is to be pierced through with the needle"8. If all goes well, the needle will poke through the ring when inserted into the skin. Then the stitching quill is placed on the next target and the process is repeated. Randle Holme notes that using the stitching quill helps "keep it as much as may be from being a scar in the flesh, and to heal it sooner."9

The stitching quill may have been reaching the end of its use as a surgical instrument during the golden age of piracy, however. Historian Kirkup says "Textbooks indicate that this method of closure was adopted by some surgeons in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and possibly later."10

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 27; 2 See Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 256 & Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, (13th unnumbered page in the beginning); 3,4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris, 1710, page 41; 5 John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, 2005, p. 340; 6 James Cooke, Supplementum chirurgiae and the Military Chest, 1655, p. 419; 7 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1676, p. 22; 8 Woodall, p. 27; 9 Randle Holmes, The academy of armory, Book III, 1688, p. 398; 10 Kirkup, p. 340

17. Uvula Spoon

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, Peter Lowe, John Woodall, James Cooke, Thomas Brugis & Randle Holme

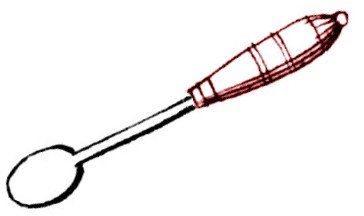

Uvula Spoon, From The Academy of the Armory, Randle Holme (1688)

The uvula spoon was also found in many of the portable surgical kits with six of the eight

authors recommending them. The uvula spoon was a somewhat curiously designed instrument. It consisted of a "small Spoon, whose handle is hollow and about 8 or 9 inches long, and is joined to the lower part of the Spoon; this Spoon being filled with Pouders that are drying and digesting"1. This description is a general one for a uvula spoon which probably explains why it was so long. (Given the size of the pocket kits and plaster boxes, an eight or nine inch instrument wouldn't have fit.)

Holme says that the spoon is "an Instrument made of Latine [this could be either black latten - a copper alloy, or white latten - a tin-plated lead] or Silver"2. The 'Latine' version was

Uvula Spoon, From Mellificium

chiurgiae, By

James Cooke, p. 117 (1685)

more likely to be found in a regular surgeon's kit than the more expensive silver one.

One use of the uvula spoon is explained by English surgeon Thomas Brugis. He says it is "to put Pepper, Salt, and fine Bole [powdered earth] in [the mouth], but putting it under the Uvula, or Palate of the Mouth, being fallen and blowing the Pouder into the Cavity behind it thorough the hollow Pipe [that served as the handle]"3. Holme provides a slightly more colorful description, suggesting that "the Surgeon takes the lower end of the Pipe in his mouth, and by blowing, scatters the pouder all about upon the Uvula, and the Palate."4

Uvula Spoon, From Cours d'Operations de chirurgie, By

Pierre Dionis,

p. 429,

(1708)

You may be wondering why salt, pepper and earth were blown under the patient's uvula. It was used for the condition that Brugis referred to: the fallen or 'relaxed' uvula. French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis explains, "Those whose Uvula is relax'd, feel it as though 'twere a morsel hung at he bottom of the Mouth, and imagine they are ready to swallow it every moment". He goes on to say that when the uvula is "red, thick and inflamed... and lengthen'd, he is to raise it up with the little Spoon made on purpose... in which he is to put a little Pomegranate-rind and Pepper beaten to a Powder". The uvula is then to be pushed up and held "for some time."5 Note that Dionis' uvula spoon does not have a hollow handle for blowing these spices down the inside of the shaft.

Of the second use of the uvula spoon, surgeon James Cooke says that

Uvula Spoon, From The Chyrurgeons storehouse, By Johannes Scultetus, p. 22 (1674)

"it may also be used to melt medicines in stopping the hole up."6 What he means by "the hole" isn't at all clear. It may refer to the hole at the end of the handle where the medicine falls into the spoon.

However, this doesn't seem the only reason for heating the spoon; Brugis says "It also serveth to warm a Medicine in, as Unguents, to dip in Tents when you want [lack] an ordinary Spoon"7.

Photo: © Dr. Robert Greenspan, Used with Permission

Uvula Spoon, from an 18th Century Surgeon's Pocket Etui, CollectMedicalAntiques.com

Sea surgeon John Woodall basically makes the same suggestion for warming medicines in the spoon in his book.8 It is possible that the uvula spoon may have taken the place of a regular spoon because space was limited in a portable kit.

Brugis adds a third function which is not mentioned by the other period authors. He advises that the uvula spoon can be employed "to pour hot Oil or Liquor into a Wound, whereto I do constantly use it in green [new] Wounds"9.

1,2 Randle Holme, The academy of armory, Book III, 1688, p. 427; 3 Thomas Brugis, Vade Mecum, 1689, p. 5; 4 Holme, p. 427; 5 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris, 1710, p. 348; 6 James Cooke, Supplementum chirurgiae and the Military Chest, 1655, p. 422; 7 Brugis, p. 5; 8 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 33