Ship's Surgeons as Barbers Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

The Ship's Surgeon as BARBER-Surgeon, Page 4

Barbering Instruments

"The term of duty of the Royal Barber was a month at a time and the rules were as follows:

ITEM it is ordained that the King's Barber shall be at the King's uprising, ready and attendant in the King's Privy Chamber, where being in readiness his Water, Basons, Knives, Combs, Scissor and such other stuff as to his room doth appertain from trimming and dressing of the King's head and beard."

(Jessie Dobson & Robert Milnes Walker, Barbers and Barber-Surgeons of London, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, p. 32)

Whether the surgeon regarded his role as barber highly or not, he must certainly have respected the instruments; as has already been discussed they could be very expensive. Sea surgeon John Woodall advises

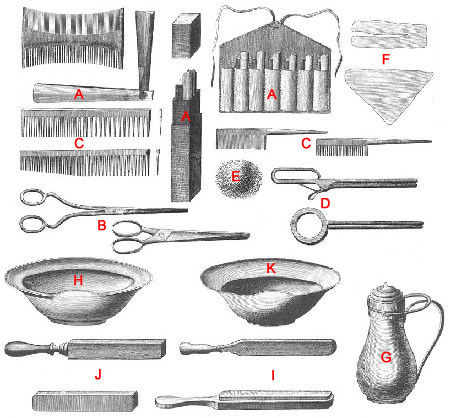

Mid-18th Century Barbering Tools from Encyclopedie des

Sciences et Metiers

Vol. 7,

p. 115-6,

by Denis Diderot (1769) Item Explanations are below.

his surgeon's mates that he must "keepe all the Instruments of the Chest, and of his owne box cleane from rusting, and to set [sharpen] his Lancets and Rasors as oft as neede is, it may be he will say to himselfe it is a base office belonging to mere Barbers and Grinders, I never gave any minde to it, &c."1

In the first edition of his book the surgions mate, Woodall comments on some of the instruments he recommends that a surgeon have, including several barbering tools. In his second edition, he provides a collected, extensive list of the shaving instruments needed aboard the East India ships. He explains that a barber on a ship "ought not to be wanting of these following necessaries."2 I have added letters to correspond with the image above right which is taken from the 1769 Encyclopedie des Sciences et Metiers Vol. 7. Note that I have combined images from the encyclopedia's pages 115-6 to better match Woodall's list, although the quantities do not necessarily match.

One Barbours case, containing,

|

Rasours foure. (A) Scissers two paire. (B) Combes three. (C) Combes-brush one. Eare-picker one. Curling Instruments. (D) Turning Instruments and Spunges. (E) Mallet one. Gravers two. phlegme one. [Fleam - for bloodletting] Paring knives two. Looking glasse one. |

Aprons three. |

The terminology was obviously different during Woodall's time. Fortunately John Kirkup explains in his introduction to a reprinting of Woodall's book that "in addition to equipment for trimming and shaving, [the barber] was provided with an ear-picker, paring knives for corn cutting and some dental implements."4 Based on Kirkup's comment, the 'gravers' must have been small tools used for cleaning or scraping the teeth. (Graver meaning a type of fine chisel.) Sweet water is most likely perfumed water to be used after shaving. (How does that fit into your general perception of 17th and 18th century sailors?)

Let's look at some of the more common barbering tools in more detail.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, from "The Office and dutie of the Surgions Mate", p. 2-3; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639 Edition, not paginated; 3 Woodall, the surgions mate, 1639 Edition, ibid; 4 John Kirikup, the surgions mate, Introduction, p. vii,

Barbering Instruments: Combs

Combs

Artist: Samuel Van Hoogstraeten

Comb Detail, Tromp-l'oeil (Still-Life) (1667)

are probably some of the oldest medical instruments the ship's surgeon had in his chest; they have been found in 5000 year old Persian archeological digs.1 The first combs were invented to remove lice from the hair, which is may be part of the reason they get little respect as an instrument.

Combs could be made of a variety of materials, including metals -silver, brass, and tin2- as well as other materials like ivory, bone, tortoise shell, horn and wood.

The type of material common items such as combs and scissors were made from could suggest the status of the owner. Metal combs required more expensive materials resulting in their being at the upper end of the scale.

Combs at the middle of the price range were made from more common materials such as tortoise shell, bone and horn. These were used by the majority of people during the golden age of piracy. This was probably because such materials could be heated to make them moldable and thus less expensive to create.

Wooden combs were at the low end of the scale and were primarily used by the poor.3

Like nearly all of the tools from this time, combs were completely made by hand. The common tortoise shell, bone and horn combs would be soaked in hot oil which softened them and allowed them to be opened with tongs. The material would then be pressed between two flat surfaces and allowed to cool.4

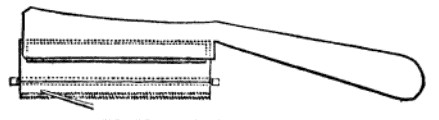

Once flat, the teeth would be cut using a a 'stadda' (a double-bladed saw) to make the gaps between

Diagram of a Stadda Saw, from Turning and Mechanical Manipulation,

Volume 2,

by Charles Holtzapffel, p. 723 (1850)

the teeth. The first blade of the stadda cut the full depth of the comb tooth gap, while the second made a notch to indicate the position for the next gap. The two saw blades were kept apart by an adjustable strip of metal to accommodate different tooth gap widths. The cut gaps were filed out with a tin wedge-shaped file fit to the size of the gap. In this way, combs could be sawed with as many as 45 teeth to an inch.5

Combs do not seem to have been very highly valued. The Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550-1820 notes that "they are found in shops valued by weight rather than by unit"6. This may be why little is said about them in period and near period sea surgeon's books. Horn, tortoise-shell and bone combs seem like the most likely type to be included in the surgeon's barbering equipment.

1 Comb, wikipedia.com, gathered 11/16/13; 2 Blue Heron Jewelry, "The History of Hair Combs", www.blueheronwoods.com, gathered 11/16/13; 3 Rory W. McCreadie, The Barber Surgeon's Mate of the 16th and 17th Century, p. 42; 4 Nancy Cox and Karin Dannehl, "Bone Comb", British History Online Website, gathered 11/16/13; 5 Cox and Dannehl, "Comb", British History Online Website, gathered 11/16/13; 6 Susan F. Craft, "Colonial American Hairbrushes and Combs", colonialquills.blogspot.com, gathered 11/16/13

Barbering Instruments: Scissors

Van Hoogstraeten

Scissors, Tromp-l'oeil

(Still-Life) (1665)

A good pair of scissors would be expensive; sea surgeon John Woodall advised the surgeon's mate that "a carefull and especiall respect [is] to be had concerning Sizers"1, probably referring both to their cost and the need to maintain them.

Scissors were made from various metals. Jean-Jaques Perret notes that small scissors could be made from "iron [steel], copper, silver and gold."2

At first consideration, precious metal scissors such as silver and gold would seem to have been used by the elite. However, military surgeon William Fabry (aka Guilelmus Fabricius Hildanus) reveals that he had scissors (and other tools) "made me by a skilful Artist in Silver, which I used only within the Town, Patients being less afraid of them than of Iron."3 The connection between precious metals and fear of operations is a curious one and the reason is not entirely clear.

However, Fabry also explains that "at Sea and at [military] Camps it is not so safe for a Chirurgeon to have them of Silver, therefore they may be very conveniently made of Iron or Steel"4. His fear is clearly that the instruments would be stolen.

Making scissors was an intricate process - like other tools, they would be entirely hand made. "Many skilled artisans (including a forger, filer, fitter, setter, grinder and various finishers) were needed [to create a pair of scissors] and up to 150 different steps went into each pair."5 You begin to see why they cost so much.

Being such dear instruments, care was required to keep the scissors in good shape. Like a razor,

Artist: Jost Amman

A Barber Cutting Hair - Note the Comb Behind His Ear (1586)

scissors would be re-sharpened. Woodall advises his surgeon's mates that they were to make sure that the scissors were "well ground, and kept cleane"6.

In addition to the obvious need to keep the edges sharp, the two blades of the scissor had to be kept tight. Scissors during the golden age of piracy would have been held together with rivets7; one can readily imagine the surgeon's mate working below deck to tighten the scissor rivet when the blade became loose through repeated use.

Woodall recommended that the surgeon's mate "have at least two paire of good sizers for to cut haire" and "also in his Plaster box one paire"8. The plaster box was the period equivalent of a first aid kit where tools, bandages and medicines would be kept. (For more on plaster boxes, see this article.) That pair would most likely be used for surgical purposes.

With regard to these instruments, Woodall sternly explained, "The manner of using them were lost labour to bee taught any Surgeons Mate, for if he be therein unskilfull he is unworthy of his place."9

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 25; 2 Jean-Jacques Perret, La Pogonotomie, interpreted by Mark Kehoe, p. 119; 3,4 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus, aka. William Fabry, Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, p. 23; 5 Carolyn Meacham, "The Cutting Edge - Antique Scissors", Elegant Arts Antiques Points of Interest - A Newsletter for Collectors, July 2006, p. 2; 6 Woodall, p. 25; 7 Meacham, p. 1; 8 Woodall, p. 25; 9 Woodall, p. 26