Ship's Surgeons as Barbers Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Next>>

The Ship's Surgeon as BARBER-Surgeon, Page 2

The Barber-Surgeon's Company and Sea Surgeons

Being a land-based group, the Company of Barber-Surgeons seems as though it would have little bearing on the practice of sea surgeons. Yet surgeons, their apprentices and surgeon's mates on ships leaving England fell under the authority of the Company during this period.

The history of this governance over sea-surgeons reaches hundreds of years back. During the Battle of Agincourt (1415), authorization was given to impress surgeons throughout England to dress the wounded. This arrangement remained in place

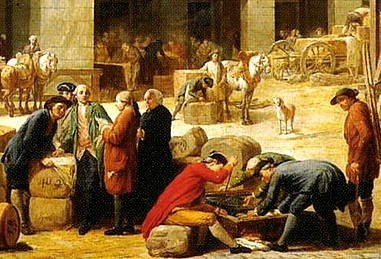

Artist: Jacob Knyff

English & Dutch Ships Taking on Stores in Port

for over a century. In Tudor times [1485-1603], sea voyages "made great demands for a supply of surgeons on board the ships."1 Surgeons were "recognised as desireable for the reassurance of the crew but also essential to maintain their numbers and fitness."2

The Company of Barber Surgeons was given the task of examining Naval sea surgeons in 1606 to be sure they were competent.3

The involvement of the Company in the lives of sea-surgeons was further codified in an order given by King Charles I in 1629. It directed "all the English ships calling at English ports to have a surgeon on board. The king ordered the Barber-Surgeons’ Company [of London] to get 97 trained Surgeons to fill the ships which had not surgeons, for when the law came into force"4.

A clause in this charter stated that, "No one was to go out from the port of London or send out any apprentice, servants, or other person from the same port, to act as surgeon to any ship whether in the service of the Crown or of a merchant, unless they, their instruments and their chests had first been examined, and allowed by two of the [Company's] Governors of the Mystery [of surgery].’"5

With this in mind, the Navy Office to the Board of Admiralty in 1635 issued a letter directing,

'The Fleet now drawing near hand ready to goe to Sea we have according to the ancient custome given orders to the Masters and Wardens of Barber Chirurgeons' Hall, to press Chyrurgeons for all the Ships of the first Fleet and have given them charge to cause them to appeare before us att the Meeting house in Mincing Lane, on fryday in the afternoon the 1st of Aprill, for the Vice Admirall and Rere Admirall to be satisfied of their Sufficiency, according to the directions received from your Lords.' (British Museum. Add. Mss. 9301. F. 57r.)'6

Artist: Thomas Rowlandson (via WikiGallery) - Portsmouth Harbor (1780)

IIn 1690, at the beginning of the golden age of piracy, arrangements were made to press surgeon's mates into service of the Royal Navy with the intent that they be dispatched to Ireland.7 So both naval and merchant sea-surgeons were governed by the Company of Barber-Surgeons for hundreds of years up through the golden age.

The influence of the Company in London was waning throughout the golden age of piracy, but it was still the organization in charge of appointing ship's surgeons. It maintained its monopoly on the appointment of Royal Naval surgeons, but its hold on the appointment of merchant-ship surgeons began to be usurped by the outlying provincial companies.8 In an attempt to maintain its position, the Company claimed national authority over the surgeons in 1710, although it had no legal basis for doing so.9

1,2 Jessie Dobson & Robert Milnes Walker, Barbers and Barber-Surgeons of London, p. 47; 3 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, p. 25; 4,5,6 Dobson & Walker, p. 48; 7 Dobson & Walker, p. 49; 8 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 28; 9 Keevil, p. 262

The Influence of the Company on the Sea-Surgeon in Port

Surgeon's apprentices in London who wanted to serve as sea-surgeons had to pay a fee of 7 guineas to be admitted to the freedom of the Company of Barber-Surgeons. They were then considered to be under the jurisdiction of the Company, just as any surgeon practicing in London. Surgeons and surgeon's mates from the provinces who were pressed into sea service were brought into the Company as foreign brothers and exempted from some of the requirements of full membership.1

Artist: Nicolas Bernard Lepicie via WikiGallery

Customs Men Examine a Chest (Likely not at ALL like a Surgeon's Chest.)

However, in 1665, the Privy Council was having trouble finding qualified surgeons and mates for their naval vessels, so they relaxed the requirement for ship's surgeons and mates to join as foreign brothers.2

The Company had also been placed in charge of assembling and inspecting the barber surgeon's medicine chests for the Navy in a 1629 order by the Privy Council [advisors to the King]. By 1690, this duty had been usurped by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, who were having their own political troubles as they battled to keep this right away from the College of Physicians.3

The Company of Barber Surgeons was still in charge of certifying the surgeon's chests, even though this right was challenged by the Royal Greenwich Hospital in 1715.4 However, the Company maintained its right in a 1729 petition from the Court which "set forth the services which the Company rendered to the State, by examining Surgeons and Mates for the Royal Navy, [and] viewing their medicine chests and instruments"5. They still had some control over sea-surgeons before they left port, particularly in the Royal Navy.

1 Kevin Brown, Poxed and Scurvied: The Story of Sickness and Health at Sea, p. 25; 2 Brown, p. 49; 3 Harold J Cook, "Practical Medicine and the British Armed Forces After the 'Glorious Revolution," Medical History, p. 16; 4 Sidney Young, The Annals of the Barber-surgeons of London, p. 350-1; 5 Young, p. 354

The Sea-Surgeon at Sea

Artist: Ludolf Backhuysen via WikiGallery

An English Royal Yacht Leaving Harbor (1691)

Although the reach of the Company of Barber-Surgeons extended to the surgeons leaving on merchant and naval ships from English ports, the situation changed once the ship had left port. The influence of the company was of little concern here. John Keevil notes that "the Company [of Barber Surgeons] could have no voice in the promotion of a surgeon [at sea], while the surgeon became largely dependent on his captain’s good opinion of him."1

The ocean was far away from the politics of the Company. Here the surgeon alone was in charge of all things medical including the concoction of medicines, dentistry, surgery and barbering.2 A surgeon was preferred over physicians, barbers and apothecaries because his skills would be most useful to men wounded at sea. Merchant voyages were, by necessity, cost conscious, so when they chose to have a medical professional on board, they usually chose a surgeon. This was why such men were able to practice so many of the tasks at sea that were reserved for other guilds and companies when on land.

1 John J. Keevil, Medicine and the Navy 1200-1900: Volume II – 1640-1714, p. 100; 2 Even in the Navy the surgeon wsa the preferred medical professional. In 1814 (admittedly almost 100 years after period), Dean King explains in A Sea of Words: Lexicon and Companion for Patrick O'Brian's Seafaring Tales that the Britiish Royal Navy 'had 14 physicians, 850 surgeons and 500 assistants surgeons. He lists no apothecaries. (Page 31)