Portable Surgical Kits Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Next>>

Portable Surgical Kits From the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

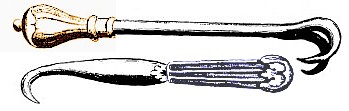

Plaster Box and Pocket Kit Instruments - Pocket Kit Only

16. Ear Picker

Included by: John Woodall

Sea surgeon John Woodall is the only surgeon in the group of eight to mention an 'ear picker' in a portable kit. Woodall includes them as part of a "Bundle of small Instruments usually brought from Germanie conteyning divers kindes" of small instruments.1 Ear pickers and their cousins, ear scoops, were not

Ear-Picker, From a Chatelaine, Wellcome Collection,

(18th c.)

uncommon items for a person of quality to have during this era. However, the only other surgeon to mention them in his book from this period was German surgeon Johannes Scultetus who described a probe "which at the end is hollow like a spoon... as an ear picker"2. Still, it seems likely that if a hygienic instrument of this type were found on a ship, it would be amongst the surgeon's gear.

Woodall was intimately familiar with the instruments supplied to the East India Company because he standardized their chests and instruments after hiring in as Surgeon-General to the company in 1613.3 He continued supplying these chests to them until his death in 1643.4 In 1626, he was also appointed to supply medicine chests to both the English army and navy.5 Every one of the medicine kits Woodall supplied would most likely have contained the instruments in the 'Bundle of small instruments'. He reasoned that "as the unexpected casualties that happneth to a man are innumerable, I see not how the Surgeon can by his wit devise instruments or remedies for all."6

Ear-Picker, From a Chatelaine,

(18th/19th c.)

The ear picker and its brother, the ear scoop, were used to remove things from the ears. The scoop seems the most obvious utensil for extracting ear wax, although it could have been useful for retrieving other foreign objects as well. French surgeon Ambroise Paré recommended using "small pincers and instruments made in the shape of ear-picks" to retrieve things that "maketh a stoppage of the ears, such as are fragments of stone, gold, silver, iron and the like metals, pearls, cherrie-stones, or kernels, peas and other such like"7. Paré was particularly concerned about removing "peas, seeds and kernels, [for] by drawing the moisture there implanted into them, swell up, and cause vehement pain by the distention of the neighboring parts"8.

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 17; 2 Johannes Scultetus, The Chyurgeons storehouse, 1674, p. 189; 3 Glen Hazelwood, "John Woodall: From Barber-Surgeon to Surgeon-General," Proceedings of the 12th Annual History of Medicine Days, March 2003, p. 120; 4 Hazelwood, p. 124; 5 Duane A. Cline, "John Woodall (1570-1643)", www.rootsweb.ancestry.com, gathered 12/11/16; 6 Woodall, p. 17; 7,8 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 412

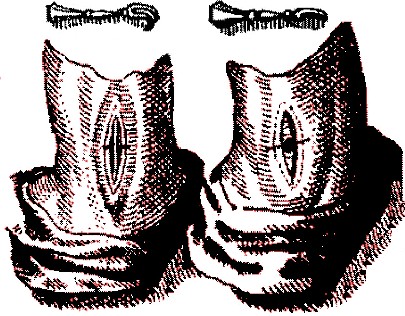

19. Extractor

Included by: William Fabry

The extractor is an odd inclusion mentioned only by German surgeon William Fabry. Of this instrument, Fabry simply notes that it is "An Extractor, to take out foreign things out of Wounds."1 Based on this description, it is tempting to say that he really means forceps but is using a different term. (Something that occurred relatively often in texts at this time.) However, immediately following that, Fabry lists "A pair of Forceps for the same use."2 So he was clearly differentiating the two instruments.

Various Extractors, From Cours d'Operations de chirurgie, By

Pierre Dionis,

p. 549,

(1708)

Unfortunately, Fabry's texts provide no illustrations of the instruments, which would have been genuinely helpful in trying to discern what he was talking about and perhaps cross-reference it with instruments shown in other texts from the time.

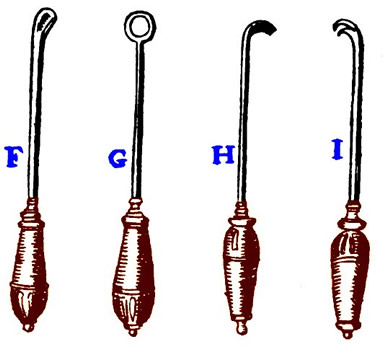

Without this, we have to look at the other period texts which do show images of the instruments and that use the term 'extractor'. In his (appropriately named) discussion of extraction of foreign bodies, French surgeon Pierre Dionis lists several bullet extractors. These include "the Spoon-Extractor F, so called from its being of that shape.... the Ring-Extractor G, which has that Name from the end of it.... the blunt Crotchet Extractor H.... [and] the cleft Crochet-Extractor I, whose Points are blunt [so] that they may not hurt the Parts."3

The difference between these types of instruments and forceps is clear - they only have a single handle and are not made to grasp foreign objects. They are instead used to catch hold of a part of them them and fish or scoop them out. Such an instrument would seem a logical choice for a portable medicine kit, space permitting.

1,2 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1676, p. 22; 3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris, 1710, p. 348;

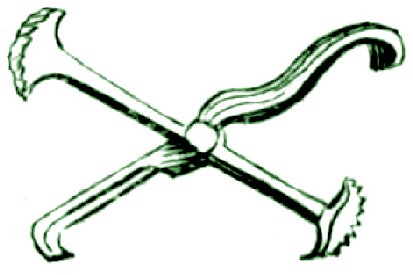

20. File

Included by: William Fabry

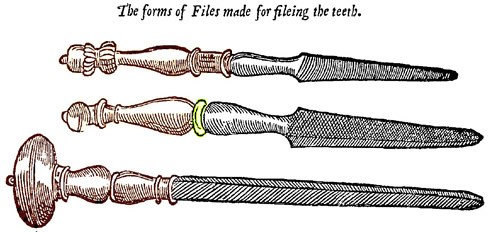

Dental Files, The Bottom Two May Be Too Large for a Pocket Kit, From The Whole Workes

of that

Famous Chirurgeon Ambrose Parey, Ambroise Paré, p. 415 (1649)Files are only mentioned by William Fabry as being a part of a pocket kit.

The file in such a kit must necessarily have been small1. Little is said about the design or make-up of such a file , although contemporary images of files from the medical texts of the time typically show it having what appears to be a wooden handle.

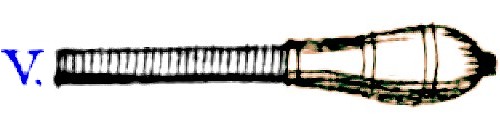

The primary use of such a file was to smooth imperfections in teeth. In this capacity, Woodall explains that files were used "to file a small snagge of a tooth, which offendethe the tongue or lips"2. Randle Holme states this a bit differently, advising that it is "to file a point of a tooth that stands out."3 Pierre Dionis gives the most expansive explanation which is appropriate to his role as a surgical instructor.

Dental File, From Cours d'Operations de chirurgie, By Pierre Dionis, p. 414, (1708)

Filing; which is practi’d in three different cases, viz. to separate them [teeth] when they grow towards one another; to level them when some of them grow too long; to even and polish them when their points turn inwards, and grate against the Tongue, or grow jagged outwards, and prick the Cheeks. On all these occasions we make use of the small File V, provided with a handle that we may hold it the more steadily, it must be very fine, that it may not shake or loosen the Teeth, and tho’ we don’t make such a hasty progress as we should with a course File, ‘tis yet better to go on more slowly. The Operator is to sustain with one or two of his Fingers the Tooth on which he is working, to prevent its breaking or splintering whilst he is Filing it. ...and this is to be done gently, and with the ordinary Care which is taken by those who follow this sort of Practice.4

Dental File, From An Explanation of the Fashion and Use of Three and fifty Instruments of

Chirurgery, By Helkiah Crooke,, p. 38, (1634)

One other use for a small file is suggested by a surgeon. John Woodall notes that in addition to filing teeth, small files can be used "to abate any end of a bone else where in the body which is fractured."5 Given that teeth are a type of bone, this should not be an altogether surprising suggestion. Surgeon James Cooke only mentions files in this capacity, advising that when bones break the surgeon must "either reduce them [put them back into their proper place], or if you cannot, taken them away with a File or Nippers."6

1 See Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, The Compleat Surgeon, 1701, p. 5 & John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 17; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 17; 3 Randle Holme, The Academy of the Armory, Book III, 1688, p. 127; 4 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1710, p. 337; 5 Woodall, p. 17; 6 James Cooke, Mellifcium chirurgiae, or the Marrow of the Chirurgery, 1693, p. 7

21. Graver/Scraper

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc

The Graver is only included in a pocket kit by Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, and he doesn't even call it by name, simply recommending that surgeons carry "a Steel Instrument to cleanse the Teeth"1.

In many ways, it is a natural choice to include a instrument in the pocket kit if the surgeon is

also

A Two-Headed Scraper/Graver, From The French Chirurgerie, By Jacques Guillemeau, (1597)

going to carry instruments such as a small dental file, a dental pelican and an ear picker. It may even have been included among the unnamed instruments in John Woodall's "Bundle of small Instruments usually brought from Germanie conteyning divers kindes"2, Of course, without more information, this supposition cannot be proven. (Woodall does not specifically list the entire contents of the small instrument kit in his "A Note of the Particular Ingrediences due to the Surgeons Chest", but he does list 'Gravers' there. It would not seem likely that gravers would be included twice.3)

It is from sea surgeon John Woodall's text that this tool is identified by name. He explains that gravers "are used to take scales of, a hard substance which use to fix themselves to teeth, causing them to become

Dental Graver, From Cours d'Operations de chirurgie, By

Pierre Dionis,

p. 414,

(1708)

loose and stinke, or be blacke in the mouth"4. However, they are given other names by other authors. French surgical Pierre Dionis recommends that when decay (which he calls 'caries', a term meaning decayed bone) becomes visible "we are to scrape it off with the Scraper T"5. Randle Holme includes them in a discussion of fleams, explaining that when the end of a fleam was "flat, yet ending in a sharp point, after the form of a leafe: ...[they] are termed Gravers, or Flegmes with Gravers"6. Holme explains that such instruments were use for "the scrapeing and cleansing of teeth from scales, and other hard substances which useth to fix themselves to the teeth."7

Since many surgical authors viewed teeth simply as bones, they used gravers on other bones as well. French surgeon Jacques Guillemeau doesn't even mention teeth, explaining that 'scrapers' were

Dental Graver, From The Academy of the Armory, Book III, By

Randle Holme,

p. 397,

(1688)

"to scrape a corrupted, cariede, and putrifyede bone."8 (This doesn't mean he never used them on teeth. Guillemeau devotes a page to instruments for teeth which focuses primarily on their extraction. So he may or may not have used his 'Scraper' to clean teeth.) Randle Holme does differentiate, suggesting that the "Chyrurgions Graver ...is used sometimes to scale and clean bones, and old corrupted teeth."9 John Woodall likewise discriminates. After expounding on how a graver could be used on teeth, he adds that it could also be used "to help to scrape or clense a bone in any other part of the body, as just occasion is offered."10

1 See Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, The Compleat Surgeon, 1701, p. 5; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 17; 3 Woodall, "A Note of the Particular Ingrediences due to the Surgeons Chest", the surgions mate, 1617, not paginated; 4 Woodall, p. 17; 5 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1710, p. 336; 6,7 Randle Holme, The Academy of the Armory, Book III, 1688, p. 427; 8 Jacques Guillemeau, The French Chirurgerie, 1597, not paginated; 9 Holme, p. 398; 10 Woodall, p. 17

22. Hone

Included by: William Fabry

A hone is "a fine whetstone"1 used to sharpen steel blades. Encyclopedist Ephraim Chambers explains, "It is

Razor Hones from Encyclopedie des

Sciences et Metiers

Vol. 7, p. 115-6, by Denis Diderot (1769)

of a yellowish Colour, being Holly-wood petrify'd or chang'd into Stone, by lying in the Water for a certain season."2

As the previous list of instruments testifies, there were a lot of blades to be sharpened. Only German surgeon William Fabry recommended the surgeon carry one, which he said was used "to set [sharpen] the Incision-knives, Lancets, &c."3 This should not be surprising, given that sharpening a blade would not usually be a task requiring immediate attention. However, Fabry included many instruments in his pocket kit that were not suggested by any other surgical author. (He clearly believed in being prepared for anything.)

1 Edward Philips, "Hoane", The New World of Words, 1671, not paginated; 2 Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopedia, Vol. 1, 1728, p. 248; 3 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1676, p. 23

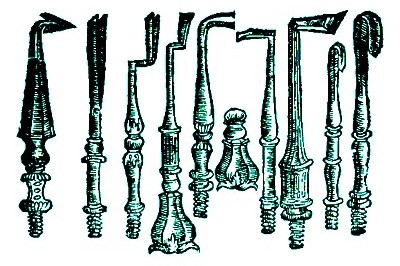

23. Hook (Tenaculum)

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, John Woodall, William Fabry & Peter Lowe

Hooks were one of the only surgical instruments to be supported by every author for inclusion in a pocket kit.

Surgical Hooks, From Mellificium chirurgiae, By James Cooke

p. 202,

(1685)

Probably the only surprising thing about hooks is that they weren't included in any of the plaster boxes, given their usefulness to surgeons. These tools were always named hooks in the documents from the golden age of piracy. In the late 17th century, they became known as 'tenaculums', which is a Latin-based word meaning "holder, holding instrument, from tenere to hold."1 However, the word 'tenaculum is not found in the surgical documents from the period, so they should more properly be called hooks here.

German surgeon Johannes Scultetus

Double and Single Hooks for Holding Incision Open in Larynx Operation,

From The Chyrurgeons storehouse, By Johannes Scultetus, p. 140 (1674)

describes one version of this tool as "a little iron hook"2, denoting its ferrous makeup. He elsewhere describes another such tool "a very sharp little hook and at the point, by degrees, bent somewhat inward"3. They were sometimes shown terminating in a single hooked prong and other times forking and ending in two parallel hooked prongs. To make the best use of space in his pocket kit, William Fabry advises including "A Hook single at one end, and two at the other."4

These hooks had multiple uses. Charles Gabriel Le Clerc explains them being "a Hook to hold up the Skin [when] cutting [it]"5. Johannes Scultetus says his 'little iron hook' "serveth to bring forth bullets."5 The other 'sharp little hook' he mentioned "is most convenient both to lift up the eye-lids, and to raise up the haw [web or spot] in the eye."7 Scultetus also discusses an operation of the Larynx in which sternohyoid muscles in the neck are to be severed. While this is being done "the distance [of the incision in the neck, see in the image above] must be kept open with a blunt hook here and there, until incision be made overthwartt"8. This is similar to the use that Le Clerc mentioned for small hooks at the beginning of this paragraph.

1' "Teneculum", Oxford English Dictionary, gathered 11/21/16; 2 Johannes Scultetus, The Chyrurgeons storehouse, 1674, p. 39; 3 Scultetus, p. 20; 4 Guliielm. Fabritius Hildanus aka. William Fabry. Cista Militaris, Or, A Military Chest, Furnished Either for Sea or Land, 1676, p. 23; 6 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, The Compleat Surgeon, 1701, p. 6; 6 Scultetus, p. 38; 7 Scultetus, p. 20; 8 Scultetus, p. 142

24. Pelican

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc

Only one author under study includes a pelican in his portable kit, suggesting it was not a common addition.

A Variety of Dental Pelicans With a Tooled Leather Pocket Case. Includes: A - Simple Hinged

Arm,

B & C - Single Armed Screw-Adjustable

Base Pelicans (C Has a Missing Arm),

D&E - Double Arm and Base Pelicans From the Wellcome Collection (16th/17th c.)

Dental pelicans were tools used to remove teeth. French surgical instructor Pierre Dionis explains that it got it's name from "the Latins [word] Pelicanus, from the resemblance it bears to the Bill of that Bird"1.

There were a variety of different configurations for the tool (as seen at right), which were all made primarily of iron or steel. Pelican A in the photo is the only one to feature a handle. which appears to be of wood. It is also worth noting that the pelicans shown here were contained in their own leather pocket kit.

Dionis explains that a pelican was "an Instrument consisting of several Branches fix’d by a Screw on the same Spring [spring refers to the central piece that to which the arms are attached]"2. He goes on to explain that "the two ends of the Spring are a little circular [sort of like serrated half moons] that they may the better fix on the Root of the rotten Tooth; and of the two Branches one is straight, and the other bent, each of them having their particular use in different cases."3

Dental Pelican, From Cours d'Operations de chirurgie, By

Pierre Dionis,

p. 414,

(1708)

The type of arms that Dionis describes don't appear on any of the pelicans shown in the above image. However, Dionis usually includes an image of the instruments he describes; this one appears in the image at left.

There are two things worth noting in this image. The first is how the lengths of each arm differ from one another. For simple pelicans with no up-and-down adjustment screw, this was a way to allow a pelican to accommodate different sized teeth. (Wide tooth = long arm & long 'spring', Medium tooth size 1 = long arm & short 'spring', Medium tooth 2 = short arm & long 'spring', and Small tooth = short arm & short 'spring'.)

The second thing of note in Dionis' image is how the bent arm appears. Dionis' sketches are pretty simple as drawings go, although he usually gets the basic idea across pretty effectively. However, the way this arm appears to be bent seems a bit off. To better see how the arm is bent on an actual instrument, see the image below right. The goal of the bent arms appears to have been

Single-Ended, Double-Armed Pelican with Bent, Adjustable Arms and an Ivory 'spring'. From the Wellcome Collection,

to be able to fix the back molars with the arm side curved so that it wouldn't interfere with either the cheek of the patient or the surgeon's thumb.

In addition to the tool itself, Randle Holme notes that pelicans were "toothed at the ends are made fit [for use on the patient] by a small boulster [cloth pad] to fit it to the tooth"4. It would seem that the cloth bolster would interfere with the grip of the 'spring', possibly even defeating the point of having the serrated teeth at the ends if the bolster were too thick.

Holme goes on to describe the technique of removing a tooth using the pelican. The surgeon could

Using a Pelican to Remove a Molar

"by the wrench or turn of a strong and nimble hand (not by pulling) raise and force up out of the Gums, any tooth it can take hold on; and that with much ease to the Patient."5

This tool had its problems, however. French surgeon Ambroise Paré recommended that, when possible, the surgeon should "have a tooth-drawer expert and diligent in the use of such toothed mullets [pelicans]; for unless one know readily and cunningly how to use them, hee can scarce so carrie himself, but that hee will force out three teeth at once, oft-times leaving that untouch’t which caused the pain."6

Their effectiveness also depended on using them on the type of teeth that most suited to be pulled with this instrument. Sea surgeon John Woodall explained that "the pullicans are the fittest instrument to draw [teeth] with; if it bee any other of the great grinders [molars], and that there bee reasonable hold on the inner side"7.

1,2,3 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., 1710, p. 340; 4,5 Randle Holmes, The academy of armory, 1688, p. 428; 6 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p. 416; 7 John Woodall, the surgions mate, 1617, p. 15

25. Rasp

Included by: Charles Gabriel Le Clerc

Like several of the other instruments in the pocket kits section, the rasp is only mentioned as being included by a single author. The term rasp was sometimes simply used to refer to a file, so it may be that Le Clerc (who said that the surgeon's pocket kit should include "several sorts of Raspatories"1) was actually referring to a small file. Dutch physician Steven Blankaart defines 'Raspatorium' as "a Chyrurgeons Instrument to Scrape or shave filthy and scaly Bones with."2 Although most of the small files were suggested for use on teeth, they were sometimes used to file broken bones as we have seen.

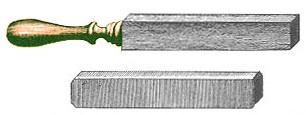

Scrapers,

Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous

Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, p. 266 (1649)

However, rasps were more typically specialized tools used on wounds of the skull by surgeons. French surgeon Ambroise Paré shows a variety of bone scrapers in his book which he calls radulæ and scalpri ('Shavers' and 'Scrapers'). These were used on "wounded or cleft bones which may be cut out ...of which divers sorts to be here decyphered, that every one might take his choice according to his mind, as as shall be best for his purpose. But all of them may be served into one handle the figure whereof I have exhibited."3

Randle Holme expands upon Paré's description, explaining that "there are diverse sorts, as some are only bent in the end and flat, but sharp in the edge: others three parts round; some round in the bent; some long’ some pointed, &c."4 Such diversity of types of this tool can best be seen in Paré's image.

Holme goes on to say that their "use is generally for the Scraping away the fissures of the Skull, as small as hairs, or Scales of rotten and decayed bones. ...[They are] to shave and scrape filthy and scaly bones.”5 Sea surgeon John Moyle used a rasp to remove rotted and scaling bone of the skull, detailing in one case where one of the ship's gun crew hit another in the head with a hand-spike. Moyle "applied the Rasp to the Caries [rotting] part [of the bone]; (having stopt the Man’s Ears with Cotton before,) and having his Head held steady. I Rasped the whole Breadth of the Caries, and so deep, till I saw a sanguine Humor [blood red fluid] follow the Rasp"6.

1 Charles Gabriel Le Clerc, The Compleat Surgeon, 1701, p. 6; 2 Steven Blankaart, The Physical Dictionary, 1702, p. 261; 3 Ambroise Paré, The Workes of that Famous Chirurgion Ambrose Parey, 1649, p.267; 4,5 Randle Holmes, The academy of armory, Book III, 1688, p. 429