Amputation Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

Amputation During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 7

The Operation: Flap Method of Amputation

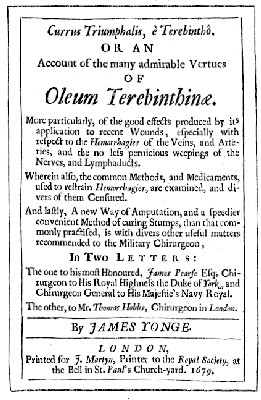

One of our sea surgeons was the first to talk about a method that would eventually become the basis of the standard way of amputating limbs: the flap method. Almost as if by after-thought, James Yonge added a letter he had written to his colleague Thomas Hobbs to his book Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô. Or an Account of the many admirable Vertues of Oleum Terebinthinæ [Turpentine]. It was not the popular two flap method espoused by Lorenz Heister in his book A General System of Surgery that would become that basis of most future amputations, but an intermediate single flap method. (Heister's book didn't come out until after the golden age of piracy in 1743.)

Yonge laid the procedure down fairly simply in his description:

"The Ligatures and the Gripe [Grip of an assistant], being made after the common manner [of the circular amputation] you are with your Catling [Catlin], or some long incision-Knife, to rase (suppose it a Leg) a flap of the membranous flesh, covering the muscles of the Calf, beginning below the place where you intend to make excision, and raising it thitherward, of length enough to cover the stump; having so done, turn it back under the

The Single Flap taken from

Traité complet d’anatomie de

l’homme, 2nd ed.

by J.M.

Bourgery, Claude Bernard,

and N.H. Jacob

hand of him that gripes [grips]; and as soon as you have severed the member, bring this flap of Cutaneous flesh over the stump, and fasten it to the edges thereof, by four or five strong stitches:

having so done, clap a Dossil [roll of lint] into the inferiour part, that one passage may be open, for any bloud, or matter may lodg between, but of that there seldom occureth any..."1

He explained that several benefits accrued to the surgeon, particularly "in most of the Amputations made at Sea in a fight, or on Land in Battels, or wheresoever acute accidents, such as Wounds, recent Lacerations require it".2 First, there was no need of "scaling the ends of those bones, [which were] left bare after the usual [circular] way of dismembering, [and must occur] before the stump can be soundly cured; ...but that where it hath been attempted, the Stumps have apostumated [become infected and formed pus], and the Caries [bone decay] come off thereby…"3 No such symptoms occurred when the single flap method was used. This led to a second advantage. As Yonge explains, "...this Method hath cured such a stump in three weeks... for this, though it be no re-unition [of divided flesh], but the consolidation of [new] flesh never before united, will yet be nevertheless effected".4

The title page of Yonge's book on Turpentine

containing a bit

on flap amputation surgery (1679) Circular amputations took 6 weeks or more to heal. Because single flap amputations healed so quickly the likelihood of infection was minimized along with "...Fever, Convulsions, Syncopes [fainting]; the effect of that pain especially at Sea, where necessaries are wanting, are here prevented partly from Natures great complacency, and the delight with which she seems to cooperate with Art… if the lips of the Wound be kept clean, close together, and free from impressions of the Ambient Air."5 (Yonge almost explained the importance of preventing sepsis here. Unfortunately, the value of antiseptics wouldn't be recognized in medicine for almost 200 years.)

Yonge explains another benefit. "Stumps this way healed, are not obnoxious to break open again on every slight rub, or knock, as do those healed by the other [circular amputation] Method".6 Finally, "...where as the other way [circular amputation], scarcely admits the laying the due stress on [prosthetics], by reason of the tenderness of the stump, or its incidency to strip and excoriate [tear off the surface of the skin)."7 (This gives us insight into just how painful and difficult the stumps of an amputee must have been during the Golden Age of Piracy.)

Yet, for all those benefits and all his praise of the operation, especially as regards soldier and sailors, Yonge himself only tried the operation once, explaining, "I think it not prudent, because there is no necessity to imitate it in such stumps: for that in curing them, we have time enough for the desquamation [scaling]".8 In fact, Yonge wasn't even the originator of this method, admitting that "…the person then principally concerned was an old Practitioner, and one that had long served in the Northern Wars... and healed most of the Amputations he made in the Army, and in Scotland, without [scaling]. I acquaint you of this for its rarity".9 Fifty years later, John Atkins wrote only of the circular method in his 1742 book The Navy Surgeon, so we can safely say that the single flap amputation method didn't catch on.

1 James Yonge, Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô., p. 110-1; 2 Ibid, p. 114; 3 Ibid, p. 108-9; 4 Ibid, p. 112; 5 Ibid, p. 117; 6 Ibid, p. 119; 7 Ibid, p. 119-20; 8 Ibid, p. 109;9 Ibid, p. 109

Stopping Blood Loss

"In this Operation, the First thing we ought to have in Intention, is the stopping of the Blood, that so when Excision is made of a Limb, we may not be at a Loss for the Apparatus, nor a Presence of

Mind to apply it: Too copious a Flux may not only be of immediate Hazard, but by dispiriting a Patient, and

Amputation de la jambe from "Traité des opérations de chirurgie"

by Rene Garengeot, p. 365 (1723)

abating of those Supplies every Part should receive, subject the Stump hereafter to the worst of Symptoms, viz. Pain, Indigestion and Mortification.

It is therefore a necessary Interruption to adjust now the properest and safest Way of stopping the Hæmorrhage; that at the Operation we may not seem plunged into Difficulties; a Thing terrifying to a Patient, and a great Hindrance to the Success of it." (John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 118)

As you may imagine, blood loss was a considerable concern for a surgeon following the amputation of a limb. There are several arteries in the arms and legs and it was up to the surgeon to keep them from spilling all their "precious liquor." As Pierre Dionis explains "the taking off a Limb is not the most difficult Task, a Butcher might have done that; but 'tis not easy for the Operator to master Blood, by stopping it with Expedition and Safety".1 He further notes that the blood loss is "a Thing terrifying to a Patient, and a great Hindrance to the Success of it."2

How did they go about it during the Golden Age of Piracy? Atkins tells his readers, "There are Three Methods in Practice: The first is by Medicines Astringent or Styptick. The second by Cauteries, actual or potential. And the third, by a Deligation of the Artery."3

Let's look at each of our three methods for stopping blood loss as well as a fourth method discovered in practice by another sea surgeon.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 408; 2 Ibid; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 118

Stopping Blood Loss: Medicines

The first method of stopping blood loss was by applications of 'restrictives' or styptic medicines. For the most part, medicines alone would not stop bleeding merely upon application. They would often be combined with other methods and/or with sticking plasters that would make soft cloth stick to the wound and help seal it.

John Atkins explains that astringents "are most successfully used... from the Circumstances of their Application"1 and "not from any irresistible... Stipticity [which can stop] ...the rapid Current of the Blood through the Arteries, which is Absurd... for when thick Pledgets are used, one compressing another, cross Cloths and Rowlers [rolling bandages], on them again, straightly [tightly] bound on, the Stump must needs be as secure from a Flux, as if a strong Compression were made with the Thumb immediately on the Vessel itself."2 Thus, the real mechanism for stopping bleeding is not the astringents medicines, but that old first aid standby, direct pressure. The medicines are there to help close the vessels off after the bandages stem the blood flow.

Atkins treats us to an extensive list of astringent medicines, explaining: "In this Class we may reckon all Earths, Terra Sigillat. Lenmia, [Terra sigillata lenmia – a red medicinal clay used as a general cure for bodily impurities] Pul. Astringens [Powdered astringents],

Bolus Vera [This is the same as Armenian or Oriental Bole - Bole being an earthy, often red, clay], Sang. Dracon. [Sanguis Draconis or "Dragon's blood" - a resinous secretion from the fruits of Doemondrops propinquus to stop bleeding] Flor. Balaust. [Flowers of wild pomegranate trees] all Vinegars and rough Wines, and to speak generally, all such Things as are dry, and have an Asperity of Taste."3

John Moyle suggests "you must sprinkle some Pulv. restringens [a powdered mixture of restringent medicines such as those mentioned by Atkins] on the mouths of the Vessels, and apply small Pedgits of Tow thereon, and on the bone; apply still a Plegit of Tow with Pouder of Myrrh. (Some use dry Tow all along)".4

Ambroise Pare suggests a complex recipe containing aloes and many of the ingredients Atkins outlines. He gives explicit instructions on how it is to be applied, explaining that it should be covered with bandages and "spread further and cover the neighboring parts; as when the Legge is cut off, it must bee laid upon the joint, and spread higher than the knee, some foure fingers upon the thigh; for it hath not onely a repercussive facultie, but it also strengthens the part, hinders defluxion by tempering the blood, aswaging paine, and hindring inflammation."5

John Woodall advises "spred your plegents ready with the restrictive stuffe... have ready the stronger restrictive powder mentioned, namely... burn'd Allome [Alum]... Vitrioll burn'd and of Precipitate... All these mixed together: This mixture I have termed the strong restrictive powder, for that it forcibly restraineth Fluxes [flows of fluid from the wound], and maketh an Eskar [Eschar - covering of skin that seals the wound.]"6 Then "take of the bottons of towe [buttons of tow - soft lint formed into the shape of a ball or button] some foure or five, wet them in the strong restrictive to be laid on the great ends of the Vaines and Arteries when they are absized".7

The other part of the medicine equation are plasters applied to pledgets and bandages to cause them to stick to the wound. Ambroise Paré tells us "we [must] shew what medicines are fitting to be applied after the amputation of a member; which are Emplasticks, as these which exceedingly conduce to greene wounds [fresh wounds]..."8 John Atkins recommends "[m]edicines of a gummy, sticky, or glutinous Nature, such as Whites of

Eggs, Hare's Hair, Aloes, Thus [Frankincense or resin of spruce-fir], Myrrh, Terebinth.

You want me to roll over so you can get a handful of what?

[turpentine] of all kinds. The Manner of using the Powders is mixing them to a Consistence with Oxycrate [water and vinegar] and Whites of Eggs, and then spreading them thick on Pledgits of Tow [absorbent pads made from inexpensive linen cloth]."9

Let's look closer at the need for "Hare's Hair" (or rabbit's fur). William Clowes gives specific suggestions for this curious ingredient. "Let your Hare hairs be the whitest and softest that is taken under the belly of the hare, and cut so fine as possible may be, and with the said powder let all be mixed together and so brought to a reasonable thickness…"10 From this we may gather that rabbit's fur would be used to give a sticky medicine body while still being soft when applied to a wound. In a similar way, Matthias Gottfried Purmann recommends "...apply[ing] the Fuss ball, with my Blood-stopping Powder, and they will do the Work effectually."11

Two other rather interesting medicines are recommended by our surgical authors for arresting blood flow. The first has already been mentioned - turpentine or, more correctly, oil from resin of Longleaf pines

Taken from "Buch der rechten kunst zü

distilieren

die eintzigen

ding" by Hieronymus Brunschwig,

title page (1500)

distilled with water. Atkins gives us quite an extensive account of this medicine, based on James Yonge's work Currus Triumpalis, é Terebinthô mentioned in the section on the Flap Method of Amputation.

"Ol. Terebinth. is of general Estimation among Astringents; Mr. Young [Yonge] celebrates it extraordinarily [recommends it] from several Experiments. First, Spreading it hot on a plain Board, it quickly became dry, with a firm gummy Integument. Painters mixing it with their Colours and Varnish, find the same Effect. Second, Dipping his Finger in reeking Blood, and then into hot Ol. Terob. it begat a sensible Straitness [tightness or rigidity]. Third, A Drop or two on Glass, or polish'd Marble, manifestly shrunk in their Expansion when dry. Fourth, Heat {one ounce} and bleed a Vein into it, you shall find it instantly coagulate, not a curdling like Acids, but a gummy Condensation; concluding it from thence, to be an incomparable Medicine for Hæmorrhages, External or Internal."12

The second interesting medicine is given by Matthias Purmann in a leg amputation performed in October of 1675. While there are a number of ingredients in his prescription, it seems to basically be some natural gum resins mixed with what he called "Vulgar Joiners Glue,"13 a type of wood glue. He explains that, "[t]his is an admirable Powder for stanching Blood, as you will soon experience by trying it. As I did upon the Patient, who was cured in less than eight Weeks."14

1 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 118; 2 Ibid.; 3 Ibid.; 4 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 58; 5 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 153; 6 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 172-3; 7 Ibid., p. 173; 8 Paré, p. 153; 9 Atkins, p. 118; 10 William Clowes, Selected Writings of William Clowes, p. 87; 11 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 210; 12 Atkins, p. 118-9; 13 Purmann, p. 211; 14 Ibid.