Amputation Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

Amputation During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 5

Patient and Surgeon Preparation

To complete the final preparations for amputation, the surgeon needed to work with the patient. First he would put the patient in the proper posture for amputation. Then tourniquets (or the period equivalent of them) would be applied. This page looks at these two elements.

Patient and Surgeon Preparation: Proper Posture

'…to alleviate the patient's intraoperative pain, and as a bonus, provide the surgeon time to amputate without haste and with smaller instruments, many patients sat for [amputation], in which position fainting may have taken place more readily than when lying down; no comment on this posture has been traced in the many works consulted." - John Kirkup, The Evolution of Surgical Instruments; An Illustrated History from Ancient Time to the Twentieth Century, p. 393

The Orlop Deck of a Swedish Ship. Imagine it filled with cargo, the men's

hammocks

and the surgeon's

quarters/temporary operating room.

(While you're imagining, remove the fluorescent lights.)

One of the problems facing a sea surgeon was space, particularly in time of battle. During his preparations for battle, a surgeon would set up a temporary operating table by placing a board across a pair of chests and covering it with a sail.1 This makeshift operating theater was established on the Orlop deck near the bottom of the ship and was likely to be quickly crowded with wounded men. It would seem that it was easier in such an environment to perform an amputation in the sitting position.

John Moyle seems to think so. "You are immediately to set this Man down on your [Surgeon's] Chest with the Limb you intend to Amputate along the Chest, (if it be the Leg) and the Part that is to be taken off [hanging] over the end of the Chest."2 Similarly, John Atkins explains that, "...your Patient should be placed on a Stool; both that he may be supported behind; and that the Assistance about you may be more commodiously used."3

Some of the other surgeons seem to prefer to have the patient lying down. Matthias Gottfried Purmann tells the surgeon to "...lay the Patient cross the Bed."4 Of course, one must remember that Purmann was a land-based surgeon and probably had the luxury of greater space. Richard Wiseman prevaricates a bit, but brings up a good point.

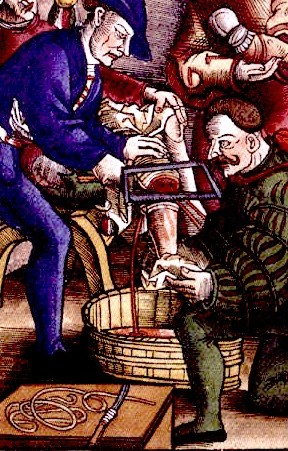

An example of a seated leg amputation

from

from Lorenz Heister's "A General System of

Surgery"

"At Sea they sit or lie [during amputation], I never took much notice which…

Yet where we have convenience to proceed more formally, we always place the Patient to our most advantage, where he may be held firm, and in a clear light, and so that our Assitents may come better about us."5 Indeed, this makes good sense - put the patient in the optimal position for the way you plan to perform the operation.

Atkins leaves us with a detailed explanation of how the surgeon should position himself, about which the other surgeons don't talk much. "As to the Surgeon's Posture, it may differ to Advantage. When there are two Bones to divide, the Inside is undoubtedly best; because taking the lesser Focil with your Saw at the same Time, with the greater, there is not that Hazard of a Fracture or Luxation; but if your Amputation is to be made above the right Knee, or Elbow, then your Right Hand should be outward: You have greater Liberty in this Posture, more Scope for performing the Operation, and stand better for applying the Dressings."6

1 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 48; 2 Ibid; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 124; 4 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 452; 5 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Chirurgia Curiosa, p. 210; 6 Atkins, p. 124

Patient and Surgeon Preparation: Period Tourniquets

During the Golden Age of Piracy, an embryonic tourniquet was in use, although it was not generally referred to by that name. English surgeons called the strands that were tied around the limb to stem the inevitable flow of blood from the severed veins and arteries 'ligatures.' One of our surgeons didn't even used these.

John Woodall advises the surgeon to have his "helpers also being ready, and having hold on the member one above, another below, & also one sitting behind".1 He further explains that "the party that had doth the upper part of his legge with all his strength, griping [gripping] the member together to keepe in the spirits & bloud: It were also very good that the saide party holding the member, the flesh and sinewes being cut asunder, should immediately draw or strip upward the flesh so much as he could, keeping his hold". 2 So Woodall would one man both squeezing off the blood flow and pulling up on the skin to keep it away from the saw.

An early example of ligatures being used in amputation.

From an illustration

by Hans Wechtlin, 1540

Richard Wiseman aptly explains the problems of attempting such a use of brawn over ligature.

"For I never yet saw any man so gripe [grip], but that still the Artery bled with a greater force than was allowable... It being so [the stump being strongly gripped], in what a huddle is the stump then dressed? But suppose the uneasie posture and the long griping tires the Griper, or that his Hand be crampt the while, what condition is the Patient then in?"3

Curiously, the use of the ligature predates Woodall's suggestion by more than a century. Ambroise Paré spells out the benefits of a ligature quite clearly in his writings from the 16th century. (I have inserted some paragraph breaks in this quote for readability.)

"...drawing the muscles upwards toward the sound parts, let them be tyed with a straite [tight] ligature a little above that place of the member which is to be cut off, with a strong and broad fillet like that which women usually bind up their haire withal; This ligature hath a threefold use;

the first is, that it hold the muscles drawne up together with the skin, so that retiring backe presently after the performance of the worke, they may cover the ends of the cut bones, and serve them in stead of coulsters or pillows when they are healed up, and so suffer with lesse pained the compression in susteining the rest of the body; besides also by this meanes the wounds are the sooner healed and cicatrized [healed over with a scar]; for by how much more flesh or skinne is left upon the ends of the bones, by so much they are the sooner healed and cicatrized.

The second is, for that it prohibites the fluxe of blood by pressing and shutting up the veines and arteries.

The third is, for that is much dulls the sense of the part by stupefying it; the animall spirits by the straite compression being hindred from passing in by the Nerves".4

Notice that none of these authors have mentioned a proper tourniquet, however. Only John Atkins calls it by name. It is worth mentioning that Atkins book was published in 1742, very late, if not slightly outside of, the Golden Age of Piracy. Most of the examples in Atkins book are from the 1720s, however, so we'll let him slide.

"We begin with fixing the Turniket: And for this Purpose, having drawn the Muscles tort upwards, we enfold the Thigh or Arm with a thick Linnen Compress. If it be the Thigh to amputate, we put also a Wadd under this enfolding Compress, on the Inside, for a better Compression on the larger Vessels that descend there: Then placing the middle Part of the Ligature exactly on it, the Ends are brought over the Compress with a double Hitch; and being tied down to the upper or outward Part of the Thigh, or Arm, the Turniket [such as a stick of wood] is put in, and twisted to a Degree sufficient to check or interrupt the Course and Motion of the Blood. This Ligature ought to be very Silken; Or other Cord, that is not too hard, but very strong; for if it should break in the Operation, (unless you are very quick in supplying its Want with a strong Gripe,) your Patient is infallibly lost."5

1 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 173; 2 Ibid, p. 174; 3 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 452; 4 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 149; 5 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 124