Amputation Page Menu: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Next>>

Amputation During the Golden Age of Piracy, Page 10

Post-Operative Procedure: Wound Dressing

"After the Operation the Patient is to be dress'd, which we are to perform with great diligence; all things being ready to that end. We direct the Servant which holds the Wrench to keep it tight during the Dressing, that the impulse of the Blood don't extend beyond the Ligature, which is not able to resist it, unless sustain'd by the whole Apparatus". (Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations, 2nd ed., p. 413)

Each of the surgical authors discuss the process of bandaging, but Dionis gives the most explicit account, along with a handy diagram of each element he used during the process. So we'll use his account as a base to discuss post-amputation bandaging sprinkled with comments from the other surgeons. Bandaging, while not nearly as exciting as cutting, is a crucial part of the healing process in this operation. This can be seen by the amount of time the period authors spend on it.

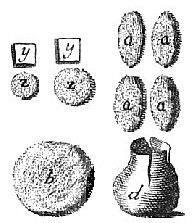

Bandaging materials taken from

A course of chirurgical operations,

2nd ed, by Pierre Dionis, p. 403

Dionis begins by "applying two little square Bolsters Y Y, in order to sustain it against the Pulsations of the arterial Blood. We lay on the two ends of the Bones two little flat Pledgets, moisten'd in Spirit of Wine, and cover all the Flesh with the thick Pledgets a a a a, charged with Astringents, laying over them the tow Stopple b, which covers the Stump".1 John Atkins concurs, detailing the coverage of the arteries with "thick round Pledgets dipped in warm Ol. Terebinth. [Spirit of Turpentine] one on another, to render it still the securer; for as that will be the deepest Part of the Stump where the Artery is, so without this Caution of raising it at least to a Smoothness, the Compression in Rowling would be least where it is most wanted".2

Rather than use Turpentine, Ambroise Paré suggests dipping all the bandages in the astringent Oxycrate.3 As mentioned in the section on Preparing the Bandages, Richard Wiseman used Oxycrate as well.4

Matthias Gottfried Purmann forgoes all of this, advising the surgeon to "apply a large sticking Plaister" as he suggested previously as an alternative to suturing the stump.5 The sticking plaster would seem to be more secure, but with the potential to adhere to newly forming skin when the bandages are changed.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 413; 2 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 125; 3 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 153; 4 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 453-4; 5 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 210

Post-Operative Procedure: Wound Dressing and the Application of a Bladder

Next, Dionis says "we are to force [the stump] into the Bladder d [see above illustration], slit on purpose to for that end, and furnished with astringent Powders".1 Purmann advises that this be "an Oxes Bladder moistened in Wine"2 while Atkins refers to it as "a large Cap armed with some astringent Mass [presumably soaked and pressed lint pledgets as discussed above], a Bladder of the like Dimensions, (made pliant by immersing in warm Water)".3 John Moyle mentions that some surgeons use a bladder "to save the upper Rowlers clean; but I have done the work as well without that."4 John Woodall suggests using "a swines blader, which is no evill course, for being once drie, you need not fear any fluxe of bloud, my selfe have used it and found it good."5

Wait...you want my WHAT?

Animals bladders have been used throughout history as a container for air and fluids. (According to one website, the first soccer balls were made in 1863 from ox or pig bladders.6) I haven't yet come across a period book explaining how such a bladder would be prepared, but in 1913, John Phin revealed that for "the amateur chemist bladders often form an efficient substitute for a much more expensive apparatus... [being] the cheapest and most convenient gasholders that can be obtained".7 Phin goes on to explain how to prepare them in a process that sounds as if it would have worked very well during period. They should be first "freed from all fat and flesh... by blowing them up and removing all superfluous matter with a sharp knife... The bladder should then be soaked in a weak solution of common washing soda and well washed, after which it is blown up as tightly as possible. ... [then it] should be filled with water and emptied two or three times, so as to wash out the inside. This tends greatly to prevent putrefaction."8 The bladder can then be dried and stored. Now you know far more than you probably ever needed about the ox bladder.

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 413; 2 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 210; 3 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 125-6; 4 John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 54-5; 5 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 174 ;6 Revealing the Magic of Everyday Life: Chapter 5 - The Science of Soccer, gathered 4/13/12; 7 John Phin, Industrial Recipes, p. 195; 8 Ibid, p. 196

Post-Operative Procedure: Wound Dressing with Stump Padding and Rollers

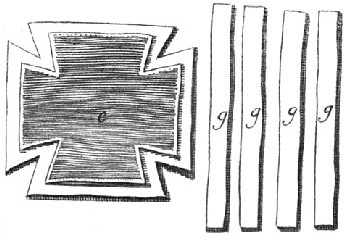

More bandaging materials taken from

A course of chirurgical operations,

2nd ed, by Pierre Dionis, p. 403

After placing the bladder on the stump, Dionis continues explaining the bandaging process. "We then lay on the Plaister e, cut or slit at the four Corners, fixing its middle part on the Stump, and causing its four Ends to come over the whole Knee, next to which is to follow the large Bolster f [e is sitting on top of f in the image at right], shap'd in the same manner, and then the four long Bolsters g g g g, the middle Parts of the three first of which are laid on the End of the Stump, representing the Figure of a Star, and the fourth is to be more than once circularly roll'd about the Stump, and withal take up and fasten the six ends of the three first."1

You may have noticed that Dionis supplies a lot of padding to end of the stump once the bladder is set on it. In Richard Wiseman's account, he uses "a Rowler with two heads begin upon the Stump, and rowl up to the next Joint, and so again about the Member, to retain your Dressings firm. Then fasten it so as that it may not be capable of falling off."2 He warns to apply defensitive medicines before putting on this double-headed roller bandage, "that you may without much bungle roul up the Member."3

Curiously, both Moyle and Woodall suggest bandaging the stump before putting the bladder on, which would seem to result in ruining those bandages if the wound inside the bladder leaked. Woodall gives colorful instructions on how the assistants to do this, beginning with "laying a flat hand close on the end of the stumpe (over plegents and padding that for a bed), and holding it so till an other [man] standing by draw up the said plegents with the said bed smooth and close: then let a third man go on with the rowling, till the first rowler be spent".4 Over that, he puts the swine's bladder and continues bandaging, explaining that "your rowling must be very Artificiall [artful?] in such a case, or all will not serve, for it exceedeth all medicines. And there is a second great care to be had in the houlder that he hold well; also remember ever to keepe a hand to the end of the stump, thrusting up the medicines close, and keeping them so, excepting ever as the rowler passeth by to make way warily for it, and stay it againe, and ever where you see the bloud springing out, there lay a slender dorsell [dossil] of towe, and rowle over it againe, continuing rowling till the bloud appeare no more".5 The fact that that Woodall worries about blood appearing on a dressing outside of the bladder makes one wonder just how good the bladders were for trapping fluids.

Dionis continues his instructions for bandaging with some detail of his own on the assistant's roles, advising "[b]efore we fix the Bandages we bend the Knee a little, in order to reduce the Stump to a Posture proper to rest

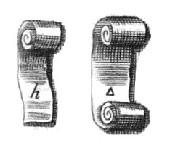

Taken from Dionis, p. 403

it self on a wooden Leg; we then take the Band h, roll'd at one End of the Stump, which we circularly roll about the Stump; when having pass'd the Knee, we roll it once over the Stump, then reascending and thus ascending alternatively, we continue 'till the whole Band is rolled up, when we fasten the End with a Pin. We next take the Band rolled at both Ends Δ, and in each Hand holding one End, we apply the Middle to the Stump, and rolling the two Ends upwards, we leave one of them to make several circular Turns, causing it to be held by a Servant whilst we Carry the other over the Stump, and return on the Knee, in order to be engaged by a fresh circular roller, and soon after again cross over the Stump, and proceed in the same course 'till we come to the End of the Band".6 John Atkins agrees with Dionis about bending the knee before applying the roller bandage, although his reason is that "otherwise the Joint contracts a Stiffness that will difficultly submit to it afterwards."7

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 413; 2 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 453-4; 3 Ibid., p. 454; 4 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 174; 5 Ibid., p. 174-5; 6 Dionis, p. 413; 7 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 126

Post-Operative Procedure: First Dressing Completion

Dionis finishes the dressing by telling the reader that the "Bands being well fasten'd with Pins, we put the Patient to Bed, placing under his Knee-pan one or two Pillows to keep up the Stump in a raised posture, and cause it to be held up by a Servant with one Hand, whilst with the other, he holds fast the Knee for several Days, in order, by this pressure, to hinder the issuing out of the Blood, and the loosning of the Bands, as also to give notice to the Churgeon if the Blood happens to escape out and run through the Ligatures."1 The assistant who was chosen to hold the knee 'for several Days' must have been the one who drew the shortest straw..

Woodall, Paré and Moyle all suggest elevating the knee with pillows,2 most likely recognizing that elevation lessens the potential for bleeding. Paré explains that the surgeon must "place the member in an indifferent posture upon a pillow stuffed with oaten huskes or chaffe, Stagges haire, or wheate branne."3 Only Dionis recommends having an assistant hold the knee up. Having a person dedicated to such a task on a ship would have been unlikely. There would be much more pressing need for the surgeon's assistants and mates elsewhere, especially during a battle. Because of this and the lack of space, Moyle basically sets amputation patients aside, telling the surgeon "let him be laid as far to the further part of your Platform as possible that some there may be room for others. For in some Fights I have had my Platform so full, as that I have not well known how to dispose of more."4

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 413; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 175, John Moyle, The Sea Chirurgeon, p. 55, Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 153; 3 Paré, p. 153; 4 Moyle, p. 55

Post-Operative Procedure: Later Dressings

Most period surgeons recommend suppurating a wound - that is encouraging the formation of puss - following an amputation. This was believed to drive the bad humors out of the body. Since pus is caused by infection, this extended recuperation.

Surgeon Dressing amputated leg from

Traite des

Operations de Chirurgie by Rene Garengeot, p. 407

"We are not to take off this [the first] Dressing in two or three Days, but rather stay longer, if we tear an Hæmorrhage at the Dressing; we gently take off the Pledgets, because the thread of the Ligature may happen to stick to it: [See?] We may then dispense with the use of the Bladder, it being no longer necessary to cover the Pledgets with Astringents, but in their stead we are to substitute other coverings, consisting of some digestive Remedy, in order to bring the Wound to Suppuration."1

How soon the first dressing should be changed depends on which surgeon's manual you read. John Woodall recommends "at the least foure daies, or longer, onely visit the patient daily and ease or take away some one rowler; as you shall see cause".2 Ambroise Paré also suggests four days, with the curious proviso, that the limb "must not be stirred after the first dressing (unlesse great necessity urge) for foure dayes in winter, but somewhat sooner in summer."3 Richard Wiseman firmly states that on the "third day take off the Dressings; and then you may cut the cross Stitch".4 Purmann recommends leaving the first dressing on for only "two days, only in the second Morning moisten the Compressors again in warm Wine, and apply them as at first. Dot the same again the second day in the Evening, if you apprehend any Danger".5 John Atkins agrees with Purmann, recommending re-dressing the wound after 48 hours.6

Atkins mentions the problem of the dressings sticking to the wound in some detail. "Our first Dressings have this in particular, of being always found troublesome to remove; for the moist and aqueous Parts of the Blood being dissipated by the Heat of the Part, the remaining Coagulum receiving some Mixture of the Ol. Terebinth. [Spirit of Turpentine] cements them like Glue: However, since it must be done, we facilitate our Work, by squeezing our Spunges of warm Water on them, till they grow supple, and are thoroughly moistened; any Roughness in bringing them away, would endanger a fresh Flux, so would a Fomentation too soon used; because the Warmth of it relaxes the solid Parts, and makes the Motion of the Blood in the Artery stronger."7

1 Pierre Dionis, A course of chirurgical operations: demonstrated in the royal garden at Paris. 2nd ed., p. 414; 2 John Woodall, the surgions mate, p. 175; 3 Ambroise Paré, The Apologie and Treatise of Ambroise Paré, p. 153; 4 Richard Wiseman, Of Wounds, Severall Chirurgicall Treatises, p. 454; 5 Matthias Gottfried Purmann, Churgia Curiosa, p. 211; 6 John Atkins, The Navy Surgeon, p. 127; 7 Ibid., p. 126